Arthur Wesley Dow stands as a pivotal figure in American art and art education at the turn of the twentieth century. An accomplished painter, printmaker, photographer, and, most significantly, an influential educator, Dow forged a unique path that synthesized Eastern artistic principles with Western practices. His work and teachings profoundly shaped the course of American modernism and established a foundation for art education that continues to resonate today. Born in Ipswich, Massachusetts, on April 6, 1857, Dow's legacy is intrinsically linked to his innovative approach to composition and design, challenging the prevailing academic traditions of his time.

Early Life and Formative Education

Dow's artistic journey began in his native New England. He received his initial art training locally, studying in Worcester under Anna K. Freeland in 1880, followed by studies in Boston with James M. Stone. Seeking to further his skills within the established European tradition, Dow traveled to Paris in 1884. This move was crucial, exposing him to the heart of the late nineteenth-century art world.

In Paris, Dow enrolled at the prestigious Académie Julian, a popular destination for American art students. There, he studied under respected academic painters Jacques-Louis Lefebvre and Gustave Boulanger. This provided him with a solid grounding in traditional figure drawing and painting techniques. However, his experiences outside the formal academy setting proved equally, if not more, transformative.

Dow spent time painting landscapes in Brittany, particularly in the artists' colony of Pont-Aven. This region attracted numerous avant-garde artists seeking alternatives to academic constraints. Significantly, Dow worked alongside figures like Paul Gauguin and likely encountered others associated with the Pont-Aven school, such as Émile Bernard. This exposure to Post-Impressionist ideas, with their emphasis on subjective expression, bold color, and simplified forms, began to challenge his academic training. He also attended the École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs in Paris, hinting at an early interest in design principles beyond easel painting.

The Transformative Influence of Japanese Art

A defining moment in Dow's artistic development occurred upon his return to the United States. While working at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston in the early 1890s, he encountered the extensive collection of Japanese prints, particularly the Ukiyo-e masters. He worked alongside Ernest Fenollosa, the museum's curator of Japanese art, who became a significant intellectual influence. Fenollosa's theories about the structural and aesthetic principles of East Asian art resonated deeply with Dow.

Dow was particularly captivated by the woodblock prints of artists like Katsushika Hokusai. He was struck by the Japanese mastery of line, the sophisticated use of flat areas of color and pattern, and the dynamic balance achieved through asymmetrical compositions. This contrasted sharply with the Western academic focus on illusionistic representation, chiaroscuro, and linear perspective.

This encounter fundamentally shifted Dow's artistic philosophy. He began to see composition not as a means of accurately depicting reality, but as an art of arranging lines, shapes, and colors harmoniously within a given space. He embraced the Japanese concept of "Notan," referring to the strategic arrangement and balance of light and dark areas or masses in a composition. This principle became central to his own work and teaching.

Artistic Style and Creative Practice

Arthur Wesley Dow's mature artistic style reflects this synthesis of Western landscape traditions and Eastern design principles. He moved away from strict naturalism towards a more simplified, decorative, and expressive approach. His primary goal was not imitation, but the creation of harmonious spatial relationships through the fundamental elements of art.

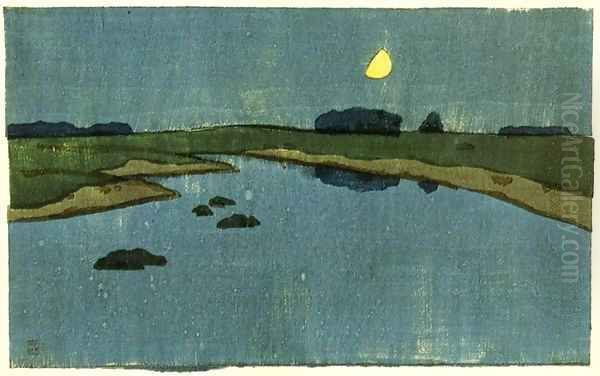

Dow worked across various media, including oil painting, watercolor, woodcut printmaking, and photography. His landscapes, often depicting his beloved Ipswich marshes or scenes from his travels, emphasize flattened perspectives, strong outlines, and carefully balanced areas of light and dark (Notan). Color was used for its emotive and decorative potential rather than purely descriptive purposes.

His woodcut prints, in particular, clearly demonstrate the influence of Japanese Ukiyo-e. Using simplified forms and a limited color palette, Dow created evocative images that captured the essence of a scene through elegant design. Works like The Marsh Stream (also known as Marsh Creek) exemplify this approach, reducing the landscape to its essential linear and tonal components.

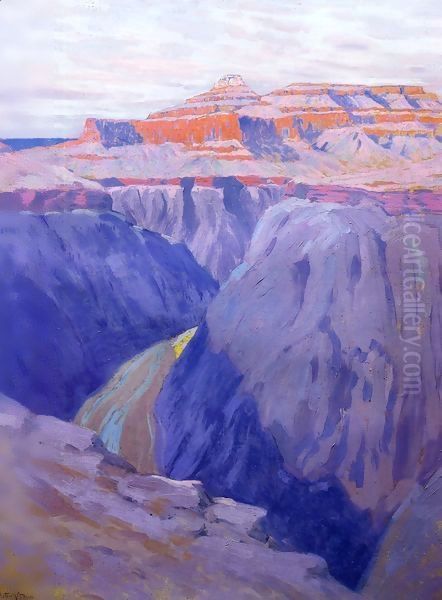

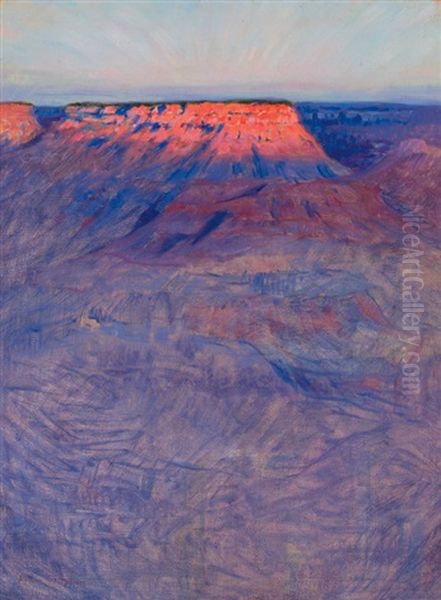

Dow also explored photography, often using cyanotype and platinum prints. His photographic compositions mirrored the principles found in his paintings and prints, focusing on pattern, texture, and abstract arrangements of form. While perhaps less known than his other work, his photography represents an early exploration of modernist aesthetics within the medium. Other significant works showcasing his style include landscape paintings like Grand Canyon and more abstract or symbolic compositions such as The Destroyer and Cosmic City, as well as evocative prints like Harbor Scene and The Glory of Shiva Temple (likely another Grand Canyon view).

The Educator: Shaping American Art Pedagogy

While Dow was a practicing artist, his most enduring impact came through his role as an educator. He believed that the traditional methods of art instruction, focused heavily on copying plaster casts and mastering realistic rendering, failed to cultivate true artistic understanding or creativity. He sought to replace this with a system based on universal principles of design.

His teaching career began in earnest in 1895 when he joined the faculty of the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn, New York, a leading institution for art and design education. He taught there until 1904, developing and refining his pedagogical methods. Concurrently, from 1897 to 1903, he also taught influential courses at the Art Students League of New York, another vital center for artistic training.

In 1904, Dow accepted the prestigious position of Director of the Fine Arts Department at Teachers College, Columbia University. He held this post until his death in 1922, making Teachers College a major center for progressive art education under his leadership. His influence extended nationwide as graduates carried his methods into schools and colleges across the country.

Dow also founded the Ipswich Summer School of Art in his hometown around 1900. This school attracted numerous students each summer, offering them the chance to learn Dow's principles through direct engagement with landscape painting, printmaking, and crafts like pottery and metalwork, further disseminating his ideas.

Composition: A Landmark Text

The cornerstone of Dow's educational philosophy was codified in his seminal book, Composition: A Series of Exercises in Art Structure for the Use of Students and Teachers, first published in 1899. This book became one of the most influential art textbooks of the early twentieth century in America, going through numerous editions.

Composition presented a radical departure from traditional art instruction manuals. Instead of focusing on representational accuracy, it laid out a systematic approach to understanding and creating art based on the fundamental elements of line, Notan (light-dark harmony), and color. Dow referred to these as the "three elements" of pictorial art.

The book provided a series of structured exercises designed to help students master these elements. Students were encouraged to create abstract arrangements, explore variations in line quality, experiment with the balance of light and dark masses, and understand color relationships based on harmony and contrast. The goal was to develop an innate sense of design and composition that could then be applied to any form of visual expression, from painting and printmaking to architecture and craft.

Dow argued that composition, or "space-filling," was the fundamental basis of all visual art, regardless of culture or historical period. By mastering these universal principles, students could develop their individual creativity rather than merely learning to imitate nature or historical styles. Composition offered a practical, hands-on method for achieving this, empowering students and teachers alike.

Influence and Enduring Legacy

Arthur Wesley Dow's influence on American art and design was profound and far-reaching, primarily channeled through his students and his widely adopted textbook. He taught or significantly influenced a generation of artists who would become key figures in American Modernism.

Perhaps his most famous student was Georgia O'Keeffe. O'Keeffe studied with Dow at Teachers College and later taught using his methods. She credited Dow with opening her eyes to new ways of seeing and composing, particularly his ideas about simplifying forms and creating harmony through light and dark (Notan). This influence is visible in her early abstract charcoals and watercolors, and arguably persisted throughout her career. Her later relationship with the photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz further placed Dow's ideas within the circle of American avant-garde art.

Other notable artists who studied with Dow or were significantly impacted by his teachings include Max Weber, a pioneering modernist painter; Charles Sheeler, known for his Precisionist paintings and photographs; Edward Steichen, a major figure in photography; and Shirley Williams. The snippets also mention Mark Rothko as a student, suggesting Dow's influence extended even to later generations, perhaps through the institutional culture he established at places like the Art Students League, which Rothko attended later.

Dow's emphasis on design principles, craftsmanship, and the integration of art into everyday life aligned perfectly with the ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement, which was gaining momentum in America during his career. He became a key figure in promoting these ideals through education, advocating for the value of handmade objects and good design in everything from pottery and textiles to printing and architecture.

His approach provided a crucial bridge between nineteenth-century traditions and the burgeoning modernist movements of the twentieth century. By emphasizing abstract structure and personal expression over academic realism, he helped pave the way for artists to explore new forms of visual language. His ideas offered a theoretical framework that validated non-representational art and design.

Anecdotes, Controversies, and Context

Despite his eventual influence, Dow's ideas were not without controversy during his lifetime. His departure from academic realism and his embrace of simplified, decorative forms derived from Japanese art were sometimes criticized. Some contemporaries found his style overly simplistic or lacking the perceived depth and technical virtuosity valued in traditional Western painting.

Similarly, his teaching methods, which prioritized abstract design exercises over meticulous life drawing, were questioned by those invested in the academic system. Critics sometimes argued that his approach was too reductive and might not adequately prepare students for complex artistic challenges. However, proponents, like Georgia O'Keeffe, recognized the aesthetic value and liberating potential of his "simple" approach.

Beyond the art world, Dow demonstrated a concern for his local environment. In the late nineteenth century, he became an advocate for the preservation of the historical architecture and natural landscapes of his hometown, Ipswich, Massachusetts. This reflects a broader sensibility, perhaps linked to Arts and Crafts ideals, valuing heritage and the harmonious relationship between human activity and nature.

Dow's later life was marked by a decline in health following a serious accident. He was injured after falling from a horse, and his condition worsened over time. Arthur Wesley Dow passed away on December 13, 1922, at the age of 65, leaving behind a rich legacy as an artist and, more importantly, as a transformative educator.

Historical Assessment and Lasting Impact

Historically, Arthur Wesley Dow is assessed less for the fame of his individual artworks and more for his revolutionary impact on art education and his role as a conduit for cross-cultural artistic ideas. While his paintings, prints, and photographs are held in major collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, it is his pedagogical framework that cemented his importance.

He is recognized as a key figure who challenged the dominance of European academicism in American art schools. By introducing principles derived from Japanese art and emphasizing universal elements of design, he offered a viable and stimulating alternative that fostered creativity and personal expression. His book, Composition, remains a landmark text, studied for its clear articulation of design principles and its historical significance in shifting art education paradigms.

Dow's synthesis of Eastern and Western aesthetics was crucial. He helped American artists appreciate non-Western traditions not merely as exotic curiosities, but as sophisticated systems with valuable lessons for contemporary practice. His focus on Notan, line, and harmonious space-filling provided artists with tools applicable to both representational and abstract work.

He played a significant role in nurturing the first generation of American modernists and was a vital force within the Arts and Crafts Movement. His belief in the power of design principles resonated across disciplines, influencing not only painters and printmakers but also craftspeople, photographers, and designers. His legacy lies in the generations of students who absorbed his ideas and carried them forward, fundamentally altering the landscape of American art and design in the twentieth century.

Conclusion

Arthur Wesley Dow was more than just an artist; he was a visionary educator who fundamentally reshaped how art was taught and understood in the United States. By looking beyond the confines of Western academic tradition and embracing the structural elegance of Japanese art, he developed a powerful and enduring system based on the universal principles of composition. Through his influential teaching at institutions like Pratt Institute and Columbia University, his widely read book Composition, and the work of his many successful students, Dow's ideas permeated American culture, fostering a greater appreciation for design and paving the way for modernism. His legacy endures in art classrooms and studios, a testament to his belief in the power of harmonious design to enrich both art and life.