Ferdynand Ruszczyc stands as a monumental figure in the annals of Polish and, by extension, Eastern European art. Active during a transformative period at the turn of the 20th century, Ruszczyc was not merely a painter but a polymath whose talents extended to stage design, graphic arts, and pedagogy. His oeuvre, deeply rooted in the Polish soil and spirit, masterfully blended Symbolist introspection with Impressionistic vibrancy and a profound, almost pantheistic reverence for nature. This article delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of an artist who captured the soul of a nation through its landscapes.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

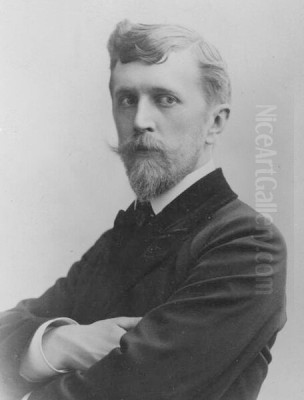

Ferdynand Ruszczyc was born on December 10, 1870, in the village of Bohdanów (Bahdanava), then part of the Minsk Governorate of the Russian Empire, now in Belarus. This region, historically intertwined with Polish culture and heritage, would profoundly shape his artistic vision. His family belonged to the Polish landed gentry, a class that often played a significant role in preserving national culture during periods of foreign domination. Though his initial academic pursuits led him to study law at the University of Saint Petersburg, the call of art proved irresistible.

The artistic heart of the Russian Empire, Saint Petersburg, offered fertile ground for his burgeoning talent. Ruszczyc soon enrolled in the prestigious Imperial Academy of Arts. Here, he came under the tutelage of two giants of Russian landscape painting: Ivan Shishkin and Arkhip Kuindzhi. Shishkin, a master of meticulous realism and detailed forest scenes, imparted a strong foundation in draftsmanship and a deep respect for the accurate depiction of nature. Kuindzhi, on the other hand, was renowned for his dramatic use of light and color, often creating almost mystical effects in his landscapes. This dual mentorship provided Ruszczyc with a rich technical and conceptual toolkit, blending empirical observation with a more poetic, evocative approach to landscape.

The Bohdanów Period and the Emergence of a Unique Voice

After completing his studies in 1897, Ruszczyc returned to his family estate in Bohdanów. This period marked a crucial phase in his artistic development. Immersed in the familiar landscapes of his youth, he began to forge a distinct artistic identity. The fields, forests, rivers, and skies of the Vilnius region (Wilno, as it was known in Polish) became his primary subjects, but he imbued them with a depth of feeling and symbolic resonance that transcended mere representation.

It was during this time that he created one of his most iconic masterpieces, Ziemia (The Land), in 1898. This powerful painting depicts freshly plowed earth under a dramatic, cloud-swept sky. The low horizon emphasizes the vastness of the sky, while the rich, dark furrows of the soil speak of toil, fertility, and the elemental connection between humanity and nature. Ziemia is often considered a quintessential expression of Polish identity, symbolizing resilience, the enduring value of the homeland, and the cyclical rhythms of life. It was a work that announced Ruszczyc's arrival as a major force in Polish art, showcasing his ability to synthesize realistic detail with profound symbolic meaning.

Other significant works from this period further explored the moods and character of the local landscape, often focusing on transitional moments – dawn, dusk, the changing seasons – which lent themselves to evocative, emotionally charged interpretations. His connection to this land was not just artistic but deeply personal, a sentiment that resonated powerfully with a Polish nation striving to maintain its cultural identity under foreign partition.

Artistic Style: A Synthesis of Influences

Ruszczyc's artistic style is a compelling fusion of several late 19th and early 20th-century currents, primarily Symbolism and Impressionism, all filtered through a distinctly Polish sensibility and a deep connection to Romantic traditions.

Symbolism and the Soul of Nature:

At its core, Ruszczyc's art is Symbolist. He sought to look beyond the surface appearance of nature to uncover deeper spiritual and emotional truths. Landscapes were not just picturesque scenes but carriers of meaning, reflecting human emotions, national aspirations, and universal themes. Works like Młyn zimą (Winter Mill, 1902) or Stare domy (Old Houses, 1903) are imbued with a sense of melancholy, history, and the passage of time. The solitary mill against a stark winter sky, or aged buildings under brooding clouds, become symbols of endurance, memory, and perhaps a certain Slavic wistfulness. His painting Nokturn – Krzyż w śniegu (Nocturne – Cross in the Snow) is a particularly poignant example, where the snow-covered cross under a moonlit sky evokes themes of faith, sacrifice, and solitude, resonating with Poland's own historical suffering and resilience.

Impressionistic Light and Color:

While deeply Symbolist in intent, Ruszczyc's technique often incorporated Impressionistic approaches to light and color. He was adept at capturing the fleeting effects of atmosphere and weather, using a vibrant palette and often broken brushwork to convey the shimmer of light on water, the glow of a sunset, or the crispness of winter air. His travels across Europe, including to France, undoubtedly exposed him to Impressionist and Post-Impressionist art, which he selectively integrated into his own vision. However, unlike many French Impressionists who focused on objective optical sensations, Ruszczyc always subordinated these techniques to the emotional and symbolic content of his work. His use of color was often more expressive and less purely observational, heightening the mood of his scenes.

Romanticism and National Spirit:

The legacy of 19th-century Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion, individualism, and the sublime power of nature, is palpable in Ruszczyc's art. This was particularly relevant in Poland, where Romanticism became intertwined with the struggle for national independence. Ruszczyc's landscapes, celebrating the beauty and character of the Polish (and historically Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) lands, carried strong patriotic undertones. His work can be seen as part of the broader Młoda Polska (Young Poland) movement, which sought to revitalize Polish culture and art at the turn of the century, often drawing inspiration from folklore, history, and the national landscape. Artists like Jacek Malczewski, Stanisław Wyspiański, and Józef Mehoffer were key figures in this movement, each exploring Polish identity through their unique Symbolist visions, and Ruszczyc's landscape painting provided a vital contribution to this national artistic renaissance. His painting Pejzaż ze Stogami (Landscape with Haystacks) beautifully captures the serene, pastoral beauty of the Polish countryside, evoking a sense of timeless connection to the land.

Early Modernist Tendencies:

While firmly rooted in late 19th-century traditions, some of Ruszczyc's works also hint at emerging Modernist sensibilities. His bold compositions, expressive use of color, and sometimes simplified forms, as seen in works like Krajobraz wiosenny (Spring Landscape), suggest an artist pushing the boundaries of traditional landscape painting. The symbolic representation of seasonal change in Krajobraz wiosenny moves towards a more abstract, universal depiction of nature's cycles.

Travels and Broadening Horizons

Ruszczyc was not an insular artist. His travels throughout Europe were instrumental in shaping his artistic perspective and exposing him to diverse contemporary art movements. He visited Germany, France, Italy, Austria, and Sweden, among other countries. These journeys allowed him to see firsthand the works of leading European artists and to absorb new ideas and techniques.

In Paris, he would have encountered the full force of Impressionism, with artists like Claude Monet and Camille Pissarro revolutionizing the depiction of light and atmosphere. He also likely saw the works of Post-Impressionists such as Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin, whose expressive use of color and form resonated with Symbolist ideals. In Germany and Scandinavia, he would have been exposed to Nordic Romanticism and Symbolism, exemplified by artists like Arnold Böcklin or Edvard Munch, whose emotionally charged landscapes and exploration of psychological themes shared common ground with his own artistic inclinations.

These experiences did not lead Ruszczyc to abandon his core vision but rather enriched it. He selectively incorporated elements that aligned with his artistic goals, always adapting them to his unique focus on the Polish landscape and its symbolic meaning. His international exposure also facilitated his participation in exhibitions abroad, bringing Polish art to a wider European audience.

Beyond the Canvas: Stage Design, Graphics, and Cultural Activism

Ferdynand Ruszczyc's artistic contributions extended far beyond easel painting. He was a highly accomplished and innovative stage designer, particularly active in Vilnius (Wilno). He collaborated with the Polish Theatre in Vilnius and other theatrical groups, creating evocative sets that enhanced the dramatic impact of numerous productions. His stage designs were characterized by a strong sense of atmosphere, an intelligent use of space, and often a painterly quality that reflected his landscape art. He understood the power of visual storytelling in the theatre, and his designs were integral to the overall artistic success of the plays.

Ruszczyc was also involved in graphic arts, producing book illustrations, posters, and other designs. His work in this field often displayed a strong sense of composition and an ability to convey complex ideas through visual means, reflecting the principles of Art Nouveau and Symbolism prevalent at the time.

Furthermore, Ruszczyc was a dedicated cultural activist and educator. He played a significant role in the artistic life of Vilnius, co-founding the Vilnius Art Society. From 1904 to 1907, he taught at the Warsaw School of Fine Arts (later Academy of Fine Arts), where his colleagues included prominent artists like Kazimierz Stabrowski (the school's first director), Xawery Dunikowski, Konrad Krzyżanowski, and Karol Tichy. His influence as a teacher helped shape a new generation of Polish artists. Later, he became a professor at the Stefan Batory University in Vilnius, where he was instrumental in establishing the Faculty of Fine Arts and served as its first dean from 1919. His commitment to art education and the development of cultural institutions was a testament to his belief in the vital role of art in society.

Contemporaries and the Artistic Milieu

Ruszczyc operated within a vibrant and dynamic artistic milieu, both in Poland and in the broader European context. His teachers, Ivan Shishkin and Arkhip Kuindzhi, provided his foundational training, but he quickly moved beyond their direct influence to forge his own path.

In Poland, he was a contemporary of the leading figures of the Young Poland movement. While Jacek Malczewski delved into complex allegories of Polish history and destiny, often featuring himself and symbolic figures, and Stanisław Wyspiański created monumental works encompassing painting, drama, and stained glass, Ruszczyc focused his Symbolist lens primarily on landscape. Józef Mehoffer, another multifaceted artist of the era, was known for his decorative style and significant stained-glass projects. Olga Boznańska, working in a more intimate, psychological vein of portraiture, shared the period's introspective mood. Landscape painters like Julian Fałat and Leon Wyczółkowski, while also depicting Polish scenes, often employed different stylistic approaches, with Fałat known for his winter scenes and watercolors, and Wyczółkowski for his Impressionistic renderings and later, more graphic style. Ruszczyc's unique contribution was his ability to imbue the landscape with a profound, almost mystical national spirit.

His time in Warsaw brought him into close contact with Kazimierz Stabrowski, a fellow Symbolist painter with an interest in theosophy and mysticism, and the sculptor Xawery Dunikowski, whose powerful, expressive figures were a hallmark of Polish modernism. In Vilnius, his collaboration with the Lithuanian composer and painter Mikalojus Konstantinas Čiurlionis is noteworthy. Čiurlionis, with his fantastical, musically inspired cosmic landscapes, shared Ruszczyc's Symbolist leanings and deep connection to his national heritage, albeit from a Lithuanian perspective. They both contributed to the rich multicultural artistic environment of Vilnius.

While direct "competition" is hard to quantify, artists of the period certainly vied for recognition and influence. Ruszczyc exhibited alongside many of these figures, including artists like Stefan Batory (mentioned as Stefanorus SzFETCHIEJ in some contexts, though this name seems less common and might be a variation or misremembering; Stefan Batory is a more recognized Polish artist of a slightly later period, but the context of exhibiting together is plausible for contemporaries). The artistic landscape was one of shared exhibitions, critical reviews, and the formation of various artistic societies, all contributing to a lively exchange of ideas and, inevitably, a degree of professional rivalry. However, the overarching spirit, particularly within the Young Poland movement, was often one of collective endeavor to elevate Polish art and culture.

Internationally, his work can be seen in dialogue with other European Symbolist landscape painters, such as the aforementioned Arnold Böcklin, or the Finnish Akseli Gallen-Kallela, who similarly drew inspiration from national myths and landscapes. The influence of Russian "mood landscape" painters like Isaac Levitan, a contemporary of his teachers, can also be discerned in the emotional depth of Ruszczyc's work. Even the more radical Symbolist visions of artists like Mikhail Vrubel in Russia, with their fragmented forms and intense spirituality, formed part of the broader artistic currents of the time.

Later Years, Declining Health, and Enduring Legacy

The later years of Ferdynand Ruszczyc's life were marked by continued artistic activity, though his health began to decline. Despite physical challenges, he remained dedicated to his art and his educational work at Stefan Batory University in Vilnius. He continued to paint, though perhaps with less frequency, and his focus remained on the landscapes that had always been his primary inspiration.

His contributions to Polish culture were widely recognized. He received numerous accolades, including the Officer's Cross of the Order of Polonia Restituta and, significantly, a medal from the French government for his contributions to culture, underscoring his international standing.

Ferdynand Ruszczyc passed away on October 30, 1936, in his beloved Bohdanów. He left behind a rich artistic legacy that continues to resonate. His works are held in major Polish museums, including the National Museums in Warsaw, Krakow, and Poznań, as well as in collections in Lithuania and Belarus, reflecting the complex cultural geography of his life and work. His paintings are frequently featured in exhibitions dedicated to Polish art and European Symbolism.

Ruszczyc's historical position is secure as one of Poland's foremost landscape painters and a key figure in the Symbolist movement. He masterfully captured the essence of the Polish landscape, transforming it into a powerful symbol of national identity, spiritual longing, and the enduring connection between humanity and the natural world. His ability to synthesize various artistic influences – Realism, Impressionism, Symbolism, and Romanticism – into a coherent and deeply personal vision marks him as an artist of great originality and depth. More than just a painter of beautiful scenes, Ruszczyc was a poet of the Polish soul, expressing its hopes, sorrows, and enduring spirit through the timeless language of the land. His influence extended to his students and helped to shape the course of Polish art in the 20th century, ensuring that his vision would continue to inspire future generations.

Conclusion: The Timeless Appeal of Ruszczyc's Vision

Ferdynand Ruszczyc remains a pivotal artist whose work transcends the boundaries of his time and place. His profound engagement with the natural world, coupled with his ability to infuse landscapes with deep emotional and symbolic meaning, gives his paintings a timeless appeal. He was an artist who understood that the land holds the memory and spirit of a nation, and through his canvases, he gave voice to the soul of Poland.

His multifaceted career – as a painter, stage designer, graphic artist, and influential educator – highlights a holistic commitment to art and culture. In an era of political uncertainty and national aspiration, Ruszczyc's art provided a touchstone of identity and a source of spiritual sustenance. Today, his paintings continue to captivate viewers with their beauty, their emotional depth, and their powerful evocation of a world where nature and spirit are inextricably intertwined. He stands as a testament to the enduring power of art to capture the intangible essence of a people and their homeland.