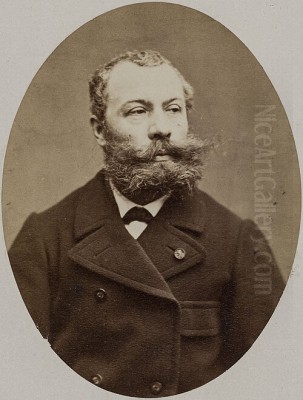

Florent Willems stands as a significant figure in nineteenth-century Belgian and French art, celebrated for his exquisite genre paintings that evoked the spirit and meticulous detail of the Dutch Golden Age. Born in Liège, Belgium, on January 8, 1823, Willems carved a distinct niche for himself, becoming renowned for his depictions of luxurious interiors, refined figures, and the subtle narratives of everyday upper-class life, rendered with remarkable technical skill. His long career, spanning much of the nineteenth century until his death in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, on October 23, 1905, saw him achieve considerable international fame and recognition, bridging the artistic traditions of Belgium and the vibrant art scene of Paris.

Early Life and Artistic Beginnings

Willems's early life in Liège set the stage for his artistic journey. While detailed accounts of his very earliest training are scarce, it's known that he moved to Mechelen (Malines) around 1832. There, he enrolled in the Academy of Art, laying a formal foundation for his burgeoning talent. Even before extensive formal training, however, Willems displayed a natural aptitude. Some accounts suggest he honed his skills partly through self-study and, significantly, through the practice of restoring old paintings. This early exposure to the techniques and materials of earlier masters likely proved invaluable, offering intimate insights into construction, color, and finish that would deeply inform his own later work.

His precocious talent quickly gained attention. A notable early success occurred when Willems was just seventeen. He submitted two paintings, reportedly titled Guard Room and Music Lesson, to an exhibition in Brussels. These works not only garnered critical acclaim, winning a first prize, but one was also purchased by King Leopold I of Belgium. Such early recognition and royal patronage undoubtedly boosted the young artist's confidence and reputation, signaling the arrival of a promising new talent on the Belgian art scene.

The Move to Paris and Salon Success

The allure of Paris, the undisputed center of the nineteenth-century art world, eventually drew Willems away from Belgium. A pivotal moment came with the Paris Salon of 1844. The Salon was the most important official art exhibition in the world at the time, and success there could make an artist's career. Willems submitted work that was exceptionally well-received by critics and the public alike. This triumph solidified his decision to make Paris his permanent home. Settling in the French capital provided him access to a wider audience, influential critics, fellow artists, and wealthy patrons.

Throughout the following decades, Willems became a regular and respected exhibitor at both the Paris Salon and the Brussels Salon. His consistent participation kept his name before the public and cemented his status as a leading painter in his chosen genre. The Salon system, despite its later criticisms by avant-garde movements, was crucial for academic and genre painters like Willems, offering a platform for visibility, sales, and the acquisition of official honors. His ability to navigate this system successfully speaks to both his artistic skill and his understanding of the contemporary art market.

Artistic Style: Reviving the Dutch Golden Age

The defining characteristic of Florent Willems's art is his deep engagement with the masters of the seventeenth-century Dutch and Flemish Golden Age. He openly admired and emulated the style, subject matter, and meticulous execution of artists like Gabriel Metsu and Gerard ter Borch. His reverence for Ter Borch, known for his refined depictions of upper-class interiors and exquisite rendering of fabrics like satin, was so pronounced that Willems earned the moniker "the modern Ter Borch."

Willems specialized in genre scenes – depictions of everyday life, albeit a highly idealized and luxurious version of it. His canvases typically feature elegant men and women, often clad in historical costumes suggesting the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, engaged in quiet activities within opulent domestic settings. Richly carved furniture, gleaming silverware, intricate tapestries, and lustrous fabrics dominate his compositions. He shared this interest in historical detail and luxurious settings with contemporaries like the French painters Jean-Léon Gérôme and Ernest Meissonier, although Willems generally focused on more intimate, less overtly dramatic or historical moments.

While deeply indebted to the Dutch masters, Willems's style was not mere imitation. His work possesses a distinctly nineteenth-century sensibility. His finish is often smoother and more polished than that of his seventeenth-century predecessors. There's a certain romanticism and sometimes a gentle sentimentality in his scenes that aligns with broader nineteenth-century tastes. He masterfully captured the play of light on surfaces, illuminating the textures of silk, velvet, and polished wood, creating an atmosphere of quiet luxury and refinement. His figures, while elegant, often convey subtle psychological nuances through pose and expression.

Technique, Detail, and Texture

A hallmark of Willems's painting is his extraordinary technical proficiency and attention to detail. His brushwork is typically precise and controlled, allowing for the faithful rendering of minute elements within the composition. He excelled particularly in capturing the textures of materials. The sheen of satin dresses, the soft pile of velvet cushions, the intricate patterns of lace, the gleam of polished wood, and the transparency of glass are all depicted with convincing realism. This virtuosity contributed significantly to the appeal of his paintings, immersing the viewer in the tangible luxury of the depicted world.

His use of light was equally sophisticated. Often employing soft, directional light, reminiscent of Johannes Vermeer or Pieter de Hooch, Willems created intimate and tranquil atmospheres. Light glances off surfaces, highlights key figures or objects, and casts gentle shadows, enhancing the sense of depth and realism within the enclosed spaces he favored. His color palette tended towards rich but harmonious tones, further contributing to the overall effect of elegance and sophistication. This meticulous technique served not just as a display of skill but was integral to conveying the mood and subject matter of his art.

Themes and Narrative Elements

The subjects Willems explored were drawn from the repertoire of traditional genre painting, updated for a nineteenth-century audience fascinated by historical settings and romantic narratives. Common themes include courtship rituals, musical interludes (ladies playing instruments or gentlemen serenading), the reading or writing of letters (often hinting at secret correspondence or important news), quiet moments of contemplation, visits between elegantly dressed individuals, and domestic scenes involving children or pets. Works like The Engagement or The Important Response clearly indicate this focus on interpersonal relationships and pivotal life moments, albeit presented with decorum and restraint.

Some sources suggest Willems drew inspiration from the historical novels of Alexandre Dumas père, whose popular works romanticized earlier French history. This literary influence might explain the slightly theatrical quality and the emphasis on costume and setting found in some of his paintings. Unlike grand historical painters who depicted major battles or political events, Willems focused on the private lives and intimate dramas of the affluent classes, offering viewers a glimpse into a world of grace, leisure, and refined sensibility. His work resonated with bourgeois patrons who appreciated the technical skill, the luxurious subject matter, and the nostalgic evocation of a seemingly more elegant past.

The Dual Role: Painter and Restorer

An interesting and significant aspect of Willems's career was his activity as an art restorer. His early experience in this field continued throughout his life, and he gained a reputation for his skill in conserving and repairing older paintings. This dual role was not entirely unique – many artists historically engaged in restoration – but it highlights Willems's deep technical understanding of painting materials and techniques across different eras. His work as a restorer likely provided him with continuous, hands-on study of the very masters he admired, potentially influencing his own painting methods.

There's even an anecdote suggesting his restoration work could be creative. It's said that while restoring one particular painting, he added the figures of a girl and her small dog, elements which subsequently became accepted as integral parts of the work's composition. Whether apocryphal or not, the story underscores his confidence and technical ability, blurring the lines between conservation and artistic intervention in a way that might seem questionable by modern standards but reflects the different approaches of the time. This expertise likely enhanced his standing among collectors and fellow artists.

Contemporaries, Collaborations, and Connections

Living and working in Paris placed Willems at the heart of a dynamic artistic community. He maintained close ties with fellow Belgian artists who were also active in Paris, most notably Alfred Stevens. Stevens, like Willems, specialized in elegant depictions of contemporary women and shared an interest in the Dutch masters, particularly Vermeer. They were friends, and their shared artistic concerns likely fostered mutual influence and exchange. Willems also collaborated occasionally with other artists, such as the still-life painter David de Noter, with whom he created works like Elegant Lady, combining figure painting with detailed still-life elements.

Willems's style, looking back to the Golden Age, positioned him somewhat differently from the dominant trends of French Realism led by Gustave Courbet or the burgeoning Impressionist movement. However, his work found kinship with other successful academic and genre painters who enjoyed significant popularity during the Second Empire and early Third Republic. Artists like Jean-Léon Gérôme, Ernest Meissonier, William-Adolphe Bouguereau, and James Tissot, while diverse in their specific subjects, shared a commitment to high technical finish and appealing subject matter that resonated with official Salon juries and wealthy international patrons.

His Belgian roots also connected him to the traditions of his home country. While he spent much of his career in Paris, his work can be seen in the context of nineteenth-century Belgian art, which included prominent historical painters like Hendrik Leys (who heavily influenced Alfred Stevens), Gustave Wappers, and Nicaise de Keyser. Willems's focus on smaller-scale genre scenes offered a different, more intimate counterpoint to the large historical canvases often favored in Belgian official art circles. His connection to his homeland was acknowledged when the French painter François Flameng painted his portrait, which was subsequently hung in Willems's native city of Liège.

International Recognition, Patronage, and Honors

Florent Willems achieved significant international recognition during his lifetime. His paintings were highly sought after, particularly by affluent collectors in France, Belgium, Great Britain, and, notably, the United States. American collectors of the Gilded Age, eager to acquire European art that signified culture and sophistication, were particularly drawn to his refined style and luxurious subject matter. Prominent collectors like Jonathan Sturges acquired his works, helping to build his reputation across the Atlantic.

His success was marked by numerous official honors. He was awarded medals at the Paris Salons of 1844, 1846, and 1855. He was made a Knight of the Order of Leopold in Belgium in 1851. France recognized his contributions by appointing him a Knight (Chevalier) of the Legion of Honour in 1853, later promoting him to Officer in 1864, and finally to Commander in 1878 – a high distinction reflecting his established position in the French art world.

Today, Willems's paintings are held in the collections of major museums around the world. Key examples include The Engagement at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, works at the Art Institute of Chicago, and The Painter at His Easel at The Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. Other representative titles that capture the essence of his oeuvre include The Wedding Dress (or Bridal Gown), The Grandparents' Feast, Visiting the Mistress, Farewell, and The Letter. His presence in these prestigious institutions confirms his historical importance and the enduring appeal of his meticulously crafted visions of elegance. His works also continue to appear on the art market, demonstrating sustained interest among collectors.

Later Life, Legacy, and Other Ventures

Florent Willems continued to paint and exhibit throughout his long career, maintaining his characteristic style and high level of technical execution. He remained based near Paris, eventually passing away in the suburb of Neuilly-sur-Seine in 1905 at the age of 82. His death marked the end of a prolific career dedicated to the celebration of historical elegance and painterly craft.

Beyond painting and restoration, Willems reportedly also engaged in design work, creating detailed sketches for furniture and carpets. This diversification, though perhaps a minor part of his output, further underscores his interest in the decorative arts and the creation of harmonious, luxurious environments, mirroring the subjects of his paintings. It suggests an artist deeply invested in the aesthetics of interior spaces and the objects within them.

Willems's legacy lies in his position as one of the foremost nineteenth-century revivalists of the Dutch Golden Age genre style. He adapted the meticulous techniques and intimate subjects of masters like Metsu and Ter Borch for a contemporary audience, creating works that were both technically brilliant and highly appealing. While his style remained largely consistent and did not engage with the radical innovations of Impressionism or later modern movements, he achieved great success within his chosen field. He stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of finely crafted, historically evocative painting and represents an important link between Belgian and French art circles in the nineteenth century.

Conclusion

Florent Willems was a painter of exceptional skill and refined sensibility. His dedication to the spirit of the Dutch Golden Age, combined with his own nineteenth-century perspective, resulted in a body of work characterized by elegance, meticulous detail, and quiet narrative charm. As both a celebrated painter of luxurious genre scenes and a respected art restorer, he occupied a unique position in the art world of his time. His international success, numerous honors, and the presence of his works in major museum collections today attest to his significance as a master craftsman who captured the allure of a bygone era for his contemporaries and for posterity.