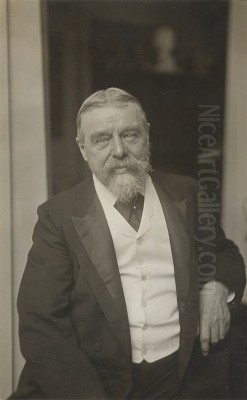

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema stands as one of the most recognizable and commercially successful artists of the late Victorian era. Born in the Netherlands but building his formidable career in Britain, he became renowned for his meticulously detailed and evocative depictions of life in antiquity, particularly the Roman Empire. His canvases transport viewers to sun-drenched marble terraces, luxurious baths, and intimate domestic scenes of a bygone world, rendered with astonishing technical skill and archaeological precision. Though his fame waned with the rise of modernism, a renewed appreciation for his unique vision and craftsmanship has secured his place as a significant figure in 19th-century art history.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in the Low Countries

Lourens Alma Tadema (later anglicized to Lawrence Alma-Tadema) was born on January 8, 1836, in the small village of Dronrijp, Friesland, in the Netherlands. His father, a notary, died when Lourens was young. Initially destined for a legal career, his artistic inclinations and a serious illness led his mother to allow him to pursue painting. This decision set him on a path that would lead him far from his Frisian roots.

In 1852, he enrolled at the prestigious Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. This city was a major artistic center, still resonating with the legacy of Flemish masters. At the Academy, Alma-Tadema studied under respected painters such as Gustaf Wappers and Nicaise de Keyser. These instructors provided him with a solid academic grounding in drawing, composition, and the techniques of oil painting, emphasizing historical subjects which were popular at the time.

A pivotal moment in his development came after leaving the Academy around 1857-1858. He entered the studio of Baron Hendrik Leys (Henri Leys), a highly regarded painter known for his historical scenes, often set in 16th-century Antwerp, rendered with meticulous detail and a somewhat archaic flavour. Leys, who also held an interest in archaeology, profoundly influenced Alma-Tadema's approach. Under Leys's tutelage, Alma-Tadema honed his precision, learned the importance of historical research, and developed a taste for depicting the past with tangible realism.

During this early period, Alma-Tadema initially focused on Merovingian and Egyptian themes, subjects less commonly explored by his contemporaries. His painting The Education of the Children of Clovis (1861) is a prime example from this phase. It depicts the young sons of the Frankish king Clovis I being taught to throw the battle-axe, showcasing his early commitment to historical narrative and detailed rendering, albeit with a darker palette than his later works. This painting gained considerable recognition when exhibited in Antwerp.

Transition, Tragedy, and the Move to London

The 1860s were a period of significant personal and professional change for Alma-Tadema. In 1863, he married Marie-Pauline Gressin Dumoulin, a French woman he met while visiting Leys's studio. They had three children, though only two daughters, Laurence and Anna, survived to adulthood. His growing reputation led to commissions and exhibitions beyond Belgium. A trip to Italy in 1863, including visits to Florence, Rome, Naples, and crucially, the excavated ruins of Pompeii and Herculaneum, had a transformative impact. The vibrant frescoes, domestic architecture, and everyday objects preserved by volcanic ash captivated him and decisively shifted his focus towards the classical world of Greece and Rome.

His personal life took a tragic turn when his wife Pauline died in 1869 after a long illness. This loss, combined with the outbreak of the Franco-Prussian War in 1870 which made continental travel and life uncertain, prompted Alma-Tadema to relocate. London, where his work was already gaining recognition thanks partly to the efforts of the influential Belgian art dealer Ernest Gambart, seemed the most promising destination. He arrived in London with his young daughters in 1870.

Even before his permanent move, Alma-Tadema had connections to London. An anecdote relates to an incident in 1866, possibly during a visit. A gas explosion occurred in the studio of his neighbour, the Dutch marine painter Hendrik Willem Mesdag (who was perhaps also visiting or temporarily residing nearby), causing damage. Alma-Tadema's family reportedly escaped harm, but the blast allegedly damaged one of his paintings, possibly The Finding of Moses. This event highlights the network of artists and the sometimes precarious nature of urban life at the time.

Once settled in London, Alma-Tadema quickly integrated into the British art scene. A key event was meeting the young Laura Theresa Epps, who came to him for art lessons. Laura was part of a highly artistic family; her sisters included the painters Ellen and Emily Epps, and she herself was a talented artist. Despite a significant age difference, Lawrence and Laura fell in love and married in 1871. Laura Alma-Tadema became a respected painter in her own right, often exhibiting alongside her husband. Their marriage was reportedly happy and collaborative, and Laura frequently appeared as a model in his paintings.

The London Years: Ascendancy and Acclaim

Alma-Tadema's arrival in London marked the beginning of the most prolific and successful phase of his career. He anglicized his first name to Lawrence and added his middle name Alma (his godfather's name) to his surname, creating the hyphenated "Alma-Tadema." This strategically placed his name early in exhibition catalogues under 'A'. His association with the dealer Ernest Gambart proved crucial, ensuring his works reached wealthy collectors in Britain and America.

He quickly established connections within the London art world, including members of the Pre-Raphaelite circle and their successors. While not a Pre-Raphaelite himself, he befriended figures like John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and Ford Madox Brown. Some critics suggest that exposure to the brighter palettes and detailed naturalism of the Pre-Raphaelites encouraged Alma-Tadema to lighten his own colours and further refine his style, moving away from the more sombre tones influenced by Leys.

His subject matter solidified around idyllic scenes of Roman and, less frequently, Greek life. He largely avoided grand historical or mythological narratives, preferring intimate glimpses into the daily lives of the ancient elite: lounging on marble benches, attending the theatre, arranging flowers, bathing in opulent settings, or engaging in quiet conversation. These scenes, often set against backdrops of stunningly blue Mediterranean skies and seas, resonated deeply with Victorian audiences.

His meticulous technique and ability to render surfaces became legendary. He conducted extensive research, amassing a vast collection of photographs and books on classical antiquity. He frequently visited the British Museum to sketch artefacts and architectural details. His collaboration with the archaeologist Louis De Taye in his earlier Belgian period indicates a long-standing commitment to accuracy. This dedication earned him both praise for his historical reconstructions and criticism from some quarters who felt his figures were merely "Victorians in togas," lacking true classical spirit.

His fame grew steadily. He was elected an Associate of the Royal Academy (ARA) in 1876 and a full Royal Academician (RA) in 1879. His paintings commanded increasingly high prices, making him one of the wealthiest artists in Britain. His success allowed him to live and work in considerable style, further enhancing his public persona.

Artistic Style: The Painter of the Victorian Classical Dream

Alma-Tadema's mature style is instantly recognizable, a unique blend of academic precision, archaeological detail, and a sensuous appreciation for beauty and texture, all filtered through a distinctly Victorian sensibility.

Classical Subject Matter and Mood

His chosen domain was the Greco-Roman world, but presented with a focus on leisure, luxury, and beauty rather than conflict or high drama. He depicted elegant figures, often women, in sunlit architectural settings – terraces overlooking the sea, opulent bathhouses, private gardens, Pompeian villas. The mood is typically serene, sometimes languid or subtly melancholic. While historically grounded, these scenes offered Victorian viewers an escapist vision of a golden age, a world of perpetual sunshine, beauty, and refined pleasure, which contrasted sharply with the industrial realities of 19th-century Britain.

Archaeological Accuracy and Detail

Alma-Tadema's commitment to historical accuracy was profound. His studios housed extensive libraries and collections of artefacts and photographs. He meticulously researched architectural forms, furniture, textiles, pottery, and even flora to ensure authenticity. Details like Roman mosaics, specific types of marble, musical instruments, and clothing styles were rendered with painstaking care. This archaeological exactitude gave his paintings an air of authority and realism that greatly appealed to an era fascinated by history and scientific discovery. However, he was not merely a copyist; he creatively synthesized elements from various sources to construct believable and aesthetically pleasing environments.

Mastery of Texture and Surface

Perhaps Alma-Tadema's most celebrated skill was his virtuosic ability to depict textures. He was particularly famed for his rendering of marble, capturing its coolness, hardness, veining, and reflective qualities with uncanny realism. This earned him the affectionate, if slightly mocking, nickname "the marbelous painter." But his skill extended to other surfaces: the shimmer of silk, the transparency of water, the intricate patterns of mosaics, the delicate petals of flowers (especially roses and poppies), the gleam of bronze, and the rough texture of stone. This tactile quality adds a powerful sensory dimension to his work.

Use of Light, Colour, and Composition

Alma-Tadema masterfully employed light to evoke the brilliant sunshine of the Mediterranean. His paintings are often bathed in bright, clear light that defines forms sharply and creates complex patterns of light and shadow. His palette became progressively brighter after moving to London, characterized by luminous blues, whites, pinks, and ochres. He often used daring compositional devices, employing steep perspectives, low viewpoints, and architectural elements like columns, doorways, and steps to frame his scenes and create a sense of depth, sometimes offering intriguing glimpses into adjacent spaces.

The Human Element

While the settings are often spectacular, the human figures in Alma-Tadema's paintings are central. They are typically depicted in moments of quiet repose, contemplation, or gentle interaction. Critics sometimes pointed out that their features and sentiments felt more Victorian than Roman. Indeed, his figures often project a sense of introspection, ennui, or romantic longing that resonated with contemporary viewers. His wife Laura and daughter Anna frequently served as models, adding a personal dimension to these classical portrayals.

Signature Works and the Opus System

Alma-Tadema produced over 400 paintings during his career, meticulously assigning an opus number to each major work in chronological order, a practice borrowed from musical composition that underscored the seriousness of his artistic enterprise. Among his most celebrated paintings are:

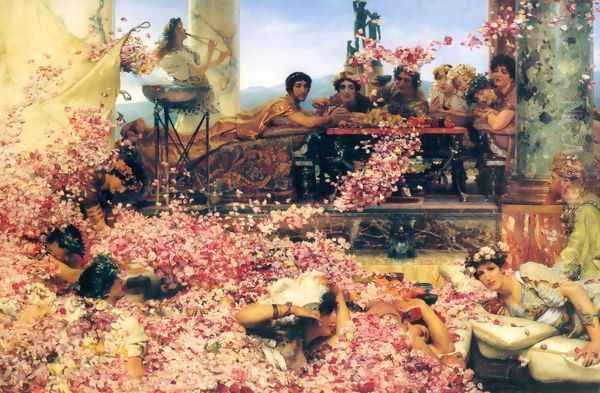

The Roses of Heliogabalus (Opus CCXCVIII, 1888): Perhaps his most famous and decadent work, depicting the Roman emperor smothering his guests under a cascade of rose petals during a banquet. It showcases his skill in rendering textures (flowers, marble, textiles) and his ability to create a scene of overwhelming sensory richness, tinged with cruelty.

Sappho and Alcaeus (Opus CCXXIV, 1881): A more lyrical work set in ancient Greece, showing the poet Sappho listening intently as Alcaeus plays the kithara. Set on a marble exedra overlooking the sea, it combines archaeological detail (the seating, the instruments) with a romantic atmosphere and beautiful light effects. It is housed in the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

The Baths of Caracalla (Opus CCCLVI, 1899): A large, complex composition depicting the bustling social life within the colossal Roman bath complex. It demonstrates his ability to handle large groups of figures and intricate architectural spaces, filled with details of Roman daily life.

Spring (Opus CCCXXVI, 1894): A vibrant depiction of a Roman spring festival procession (possibly the Floralia). Children and women laden with flowers descend a marble staircase. The painting is notable for its bright colours, joyful atmosphere, and meticulous rendering of flowers and architectural details. It is now in the Getty Museum, Los Angeles.

A Favourite Custom (Opus CCCXCI, 1909): A quintessential Alma-Tadema subject, showing women bathing and relaxing in a sumptuously decorated Roman bath. It exemplifies his mastery of depicting marble, water, and the human form in a setting of luxurious tranquility.

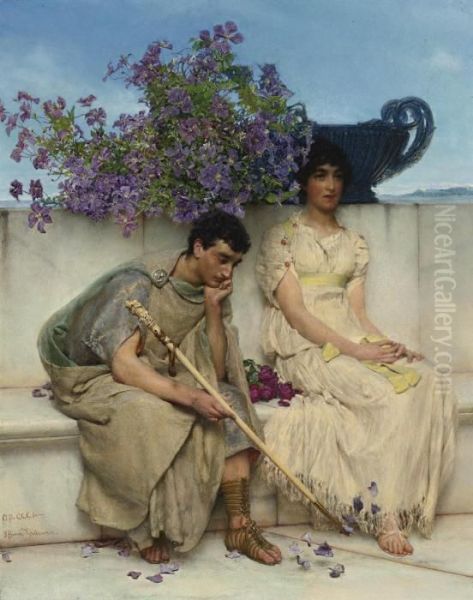

An Eloquent Silence (Opus CCC, 1890): A deceptively simple composition showing a Roman couple seated on a marble bench overlooking the sea at sunset. The title suggests unspoken emotions, capturing the quiet intimacy and romantic sensibility often found in his work.

The Finding of Moses (Opus CCCLXXVII, 1904): A later work returning to an Egyptian theme, depicting Pharaoh's daughter discovering the infant Moses among the reeds. It is notable for its grand scale, elaborate detail, and rich colour palette, demonstrating his continued ambition late in his career. This painting fetched record prices when sold in the 21st century, highlighting his market revival.

Unconscious Rivals (Opus CCCXXIII, 1893): An intimate scene showing two Roman women, one reclining languidly while the other arranges flowers, perhaps unaware they might be rivals for the same affection. The setting, a room filled with flowers and luxurious objects, is rendered with typical precision.

These works, among many others, cemented Alma-Tadema's reputation as the pre-eminent painter of classical antiquity for the Victorian age, offering a vision that was both learned and alluring.

The Alma-Tadema Household: Centers of Art and Society

Alma-Tadema's success enabled him to create extraordinary domestic environments that were artworks in themselves. His homes became famous extensions of his artistic persona and served as important social hubs in the London art world.

Initially, he lived in Townshend House near Regent's Park. After it was damaged by a canal barge explosion in 1874, he undertook extensive renovations, incorporating Pompeian-inspired decorations and showcasing his growing collection of artefacts.

In 1883, he purchased a larger property at 17 (later renumbered 44) Grove End Road in St John's Wood, previously owned by the painter James Tissot. Alma-Tadema spent years transforming this house into a spectacular Greco-Roman fantasy palace. It featured a stunning studio with a domed apse covered in aluminium leaf (to simulate silver), walls lined with exotic woods and onyx, Byzantine columns, and carefully designed furniture, much of it based on ancient models. Other rooms had equally elaborate themes, incorporating Dutch, Japanese, and Moorish elements alongside the dominant classical style. The house was filled with his collections of antiques, textiles, and curiosities.

This house became a legendary venue for lavish parties and musical evenings, attended by artists, writers, musicians, actors, and patrons. Guests included figures like the composer Ignacy Jan Paderewski, the writer Henry James, and fellow artists such as John Singer Sargent and Lord Leighton. The house itself frequently appeared as a backdrop or source of details in his paintings, blurring the line between his life and his art.

The artistic atmosphere extended to his family. His second wife, Laura Theresa Alma-Tadema (née Epps), was a successful painter specializing in domestic scenes often in Dutch 17th-century style, exhibiting regularly at the Royal Academy. His daughter from his first marriage, Anna Alma-Tadema, also became a painter, known for her watercolours of interiors, portraits, and still lifes, often depicting the family's remarkable home. Another daughter, Laurence Alma-Tadema, became a writer and poet. The Grove End Road house was thus not just a home but a vibrant artistic ecosystem.

Professional Honours and International Standing

Alma-Tadema's career was marked by numerous accolades, reflecting his high standing both in Britain and internationally. His election as a Royal Academician in 1879 was a key milestone. He exhibited regularly at the RA's Summer Exhibition, where his works were eagerly anticipated.

He received honours from numerous European countries, including membership in academies in Amsterdam, Munich, Berlin, Madrid, and Vienna. He was awarded the Pour le Mérite for Arts and Sciences by the German government. In Britain, his status was confirmed when he was knighted by Queen Victoria in 1899, becoming Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema. One of the highest honours came in 1905 when he was appointed to the prestigious Order of Merit by King Edward VII, an award limited to only 24 living recipients, recognizing distinguished service in the arts, learning, literature, and science.

His paintings were sought after by wealthy industrialists and collectors across Europe and America, including figures like William Vanderbilt. He also undertook decorative projects, including designs for furniture (notably for Henry Gurdon Marquand's New York mansion, including a famous piano) and theatrical productions, such as sets and costumes for Henry Irving's productions of Coriolanus and Cymbeline at the Lyceum Theatre.

Collaborations, Connections, and Artistic Circle

Throughout his career, Alma-Tadema maintained connections with a wide network of artists, dealers, patrons, and intellectuals. His early training connected him to Gustaf Wappers, Nicaise de Keyser, and crucially, Hendrik Leys. His relationship with the dealer Ernest Gambart was vital for launching his international career.

In London, his circle included the Pre-Raphaelites and their associates like Millais, Rossetti, and Burne-Jones, although his style remained distinct. He was friendly with other prominent Victorian classicists like Lord Leighton and Edward Poynter. His neighbourly connection with Hendrik Willem Mesdag in the 1860s points to his Dutch-Belgian network. His collaboration with the Belgian photographer Joseph Dupont, who provided photographic studies for details, shows his pragmatic use of modern technology to aid his meticulous process, even though he did not take photographs himself.

His relationship with the writer Oscar Wilde was reportedly complex; Wilde admired his work but also satirized the aesthetic sensibilities of the era. Alma-Tadema also interacted with fellow European artists interested in classical themes, such as the Belgian painter Eugène Simiand. His pupil Solomon J. Solomon became a notable painter in his own right, known for his portraiture and large dramatic scenes. His wife Laura and daughter Anna were integral parts of his artistic life, creating a unique family dynamic within the London art scene.

Later Career, Death, and Legacy

Alma-Tadema remained highly productive into the early 20th century, continuing to paint his signature classical scenes with undiminished skill, though arguably with less innovation than in his middle period. He maintained his style even as artistic tastes began to shift dramatically with the advent of Post-Impressionism and Fauvism. While still commercially successful, critical opinion began to turn against academic painting.

In the summer of 1912, while seeking treatment for a stomach ulcer at a spa in Wiesbaden, Germany, Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema died on June 25th, aged 76. He was buried in the crypt of St Paul's Cathedral in London, a rare honour for an artist, signifying his immense stature at the time of his death.

His memorial exhibition was held at the Royal Academy in 1913. However, the tide of modernism rapidly eclipsed his fame. For much of the 20th century, his work was dismissed by critics as sentimental, overly photographic, and irrelevant to the concerns of modern art. His paintings, once commanding huge sums, could be bought relatively cheaply. A joke from the 1960s captured this decline: it was said that if someone stole an Alma-Tadema, the owner would demand the thief commit suicide.

The Revival and Enduring Influence

The reassessment of Victorian art began in the 1960s, and Alma-Tadema's reputation started to recover. Critics and art historians began to appreciate his extraordinary technical skill, his imaginative reconstruction of the past, and his role within the cultural context of his time. Exhibitions and publications brought his work back into the public eye.

His influence proved surprisingly persistent, particularly in popular culture. His detailed and atmospheric depictions of the ancient world profoundly impacted Hollywood filmmakers creating historical epics. Early pioneers like Cecil B. DeMille drew inspiration from his compositions for films like Cleopatra (1934). This influence continued through films like Ben-Hur (1959) and reached a new peak with Ridley Scott's Gladiator (2000), whose production designer acknowledged Alma-Tadema's paintings as a key visual reference for recreating the look and feel of ancient Rome.

By the late 20th and early 21st centuries, his paintings once again commanded high prices at auction. Major retrospectives, such as the one held at Leighton House Museum in London in 2017, celebrated his achievements and introduced his work to new generations. Museums worldwide proudly display his works, recognizing him as a master of academic painting and a key figure in the Victorian fascination with the classical past.

Conclusion

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema carved a unique niche in 19th-century art. His fusion of meticulous archaeological detail, brilliant technical execution, and romanticized visions of ancient Greece and Rome created a powerful and enduring appeal. He offered his Victorian audience meticulously crafted escapes into a world of beauty, luxury, and sunshine. While his critical fortunes fluctuated dramatically after his death, his skill was never truly in doubt. Today, he is recognized not just as a painter of immense talent and commercial success, but as an artist whose work continues to fascinate, influencing even modern media like cinema, and offering a captivating window onto the aspirations and aesthetics of the Victorian era's engagement with the classical world. His legacy lies in the sun-drenched marble vistas and intimate ancient scenes that remain instantly recognizable and continue to enchant viewers.