Pierre Roy stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of early 20th-century French art. Born in Nantes, France, on August 10, 1880, and passing away in Milan, Italy, on September 26, 1950, Roy carved a unique niche for himself primarily within the Surrealist movement, while also demonstrating strong affinities with Magic Realism and absorbing influences from Dadaism. His meticulously rendered paintings, often featuring uncanny arrangements of everyday objects, secured him a place in the annals of modern art, recognized for their quiet yet profound disturbance of the ordinary.

It is pertinent to address a point of potential confusion regarding his biographical details. Some disparate sources, likely referencing different historical individuals bearing the same name, present conflicting birth and death dates, including suggestions of origins in the 17th or mid-19th centuries (such as 1643-1721 or born 1860). However, the established and widely accepted timeline for Pierre Roy, the Surrealist painter discussed herein, is definitively 1880-1950. This timeframe aligns perfectly with his documented artistic activities and associations within the Parisian avant-garde.

Early Life and Parisian Immersion

Born into a family connected to the arts (his father was involved with the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Nantes), Roy's early life in the port city of Nantes likely exposed him to a variety of visual stimuli. However, like many aspiring artists of his generation, he was drawn to the magnetic pull of Paris, the undisputed center of the art world at the turn of the century. He relocated to the capital, initially pursuing studies in architecture before dedicating himself fully to painting around 1905.

His formative years in Paris were crucial. He absorbed the vibrant artistic atmosphere, witnessing the decline of Impressionism and the rise of Fauvism, Cubism, and other revolutionary movements. A pivotal moment in his early career was establishing a deep and lasting friendship with the Italian-born painter Giorgio de Chirico. De Chirico, whose own "Metaphysical Painting" style explored dreamlike cityscapes and enigmatic juxtapositions of objects, proved to be a significant influence and a key connection for Roy. It was De Chirico who introduced Roy into the burgeoning Surrealist circles, recognizing a shared sensibility in their approach to the uncanny and the subconscious.

Embracing Surrealism

The aftermath of World War I saw the emergence of Surrealism, formally launched by André Breton's Surrealist Manifesto in 1924. The movement sought to unlock the power of the unconscious mind, drawing inspiration from dreams, psychoanalysis (particularly the work of Sigmund Freud), and automatic techniques. Pierre Roy found a natural home within this milieu. His existing inclination towards depicting the strange within the familiar resonated with the Surrealist project.

Roy was an active participant in the early, formative years of the movement. He was notably included in the very first group exhibition of Surrealist painters, held at the Galerie Pierre Loeb in Paris in 1925. This landmark exhibition featured works by artists who would become central to the movement, including Max Ernst, Joan Miró, Man Ray, and André Masson, alongside Roy and his friend De Chirico. Roy's contribution did not go unnoticed. The influential art critic André Salmon, observing Roy's distinctive style at this show, famously declared him the "true father of Surrealism," acknowledging his pioneering approach to rendering dreamlike realities with startling clarity.

Further cementing his place within the movement, Roy was among the first artists showcased at the official Galerie Surréaliste when it opened in Paris in 1926. This gallery served as a crucial hub for the group, hosting exhibitions and fostering dialogue. Roy's participation in these key early events underscores his importance during Surrealism's initial phase. He also engaged with the Parisian art scene more broadly, frequently exhibiting his work in the established Paris Salons, demonstrating an ability to navigate both avant-garde circles and more traditional venues. His activities extended to gallery management; he briefly ran his own gallery and, in 1927, served as the artistic director for the Galerie de la Goutte d'Or.

Artistic Style: Precision and the Uncanny

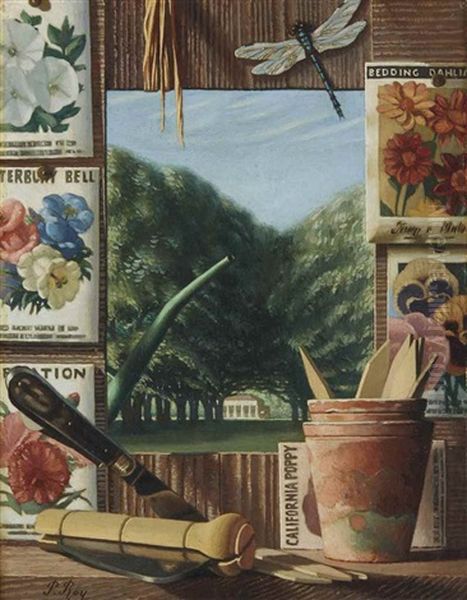

Pierre Roy's artistic signature lies in his unique combination of meticulous, almost academic realism in technique with profoundly illogical or unsettling subject matter. Unlike some Surrealists who embraced automatism or biomorphic abstraction (like Miró or Masson), Roy meticulously crafted his compositions. He painted everyday objects – eggs, ribbons, shells, tools, architectural fragments, scientific instruments, toys – with sharp focus, clear light, and careful attention to texture and form.

The Surrealist effect in Roy's work arises not from distorted forms but from the juxtaposition of these realistically rendered objects. He placed them in unexpected combinations and environments, stripping them of their normal context and function, thereby imbuing them with a sense of mystery, poetry, or latent threat. This approach aligns closely with the principles of Magic Realism, a related but distinct current in 20th-century art where fantastical or dreamlike elements are woven into a realistically depicted world. Roy is often considered a key exponent of this style alongside his Surrealist identity.

His work often evokes a sense of quiet stillness, a frozen moment where the mundane has become charged with hidden meaning. The clarity of his style paradoxically enhances the feeling of unease or wonder. It’s as if the viewer has stumbled upon a secret, meticulously arranged tableau whose logic remains tantalizingly out of reach. This precision distinguishes him from the more fluid or chaotic styles of some contemporaries but shares ground with the sharp, detailed dreamscapes of artists like Salvador Dalí and Yves Tanguy, or the perplexing visual riddles of René Magritte.

Influences and Diverse Techniques

While Surrealism and Magic Realism are the primary labels associated with Roy, his artistic practice also reveals the impact of Dadaism. Emerging during World War I, Dadaism was characterized by its anti-art stance, its embrace of absurdity, chance, and ready-made objects, and its critique of bourgeois values. Roy's interest in collage, a technique pioneered by Cubists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque but enthusiastically adopted and transformed by Dadaists such as Max Ernst and Kurt Schwitters, reflects this connection.

The provided sources mention Roy creating Dadaist woodcuts, cardboard silhouettes, and collages. These techniques allowed for different modes of expression, often incorporating found materials and emphasizing fragmented or constructed realities. The mention of "primitive art" traces in his work also aligns with a broader modernist interest in non-Western art forms and children's art, seen as sources of greater authenticity and directness, a trend visible in the work of artists from Paul Gauguin to Picasso and members of the German Expressionist group Die Brücke (like Ernst Ludwig Kirchner).

Roy's engagement with these varied techniques demonstrates a versatile artistic mind, exploring different avenues for expressing his unique vision. Whether through the precise illusionism of his paintings or the assembled fragments of his collages, his goal remained consistent: to reveal the extraordinary hidden within the ordinary.

Representative Works and Recurring Themes

Several specific works help illuminate Roy's artistic concerns. Danger on the Stairs (often dated 1927 or 1928) is frequently cited as a prime example of his Magic Realist style. While interpretations vary, the image typically depicts a staircase, a common motif suggesting transition or descent, often accompanied by an incongruous object, such as a large snake, creating an atmosphere of palpable, yet ambiguous, threat invading a domestic space. Another mentioned title, Snake on the Stairs, likely refers to the same or a closely related work, exploring themes of hidden fears and the unsettling intrusion of the wild or subconscious into the ordered world.

Other listed titles provide a glimpse into his recurring subjects: Butterflies (nature, fragility, transformation), Armor (protection, history, emptiness), Pineapple (exoticism, texture), Cauliflower (the mundane elevated), Seascape (vastness, mystery), Interior (domestic space made strange). Works like Deceive My Eyes and Shirley (possibly a playful title referencing trompe-l'oeil) and Interesting Physique hint at a sense of visual wit or commentary. The Woman Painter and Girl in Landscape suggest occasional forays into figurative subjects, likely treated with the same enigmatic quality as his still lifes. California Poppy indicates an interest in botanical subjects, rendered with his characteristic precision.

Common threads run through these works: the isolation of objects, the creation of silent, stage-like settings, the interplay between the natural and the man-made, and an overarching mood of contemplative mystery. His paintings often feel like visual puzzles or rebuses, inviting interpretation while resisting easy solutions. They tap into themes of memory, childhood (implied by toys or simple objects), and the quiet anxieties lurking beneath the surface of everyday life.

Literary Interests: The World of "Comptines"

Beyond his visual art, Pierre Roy demonstrated a fascinating interest in literature, specifically in the realm of children's culture. He collected and published "comptines," traditional French nursery rhymes or counting-out rhymes often characterized by their playful language, nonsensical elements, and rhythmic structures. This activity might seem tangential, but it connects deeply with the core interests of Surrealism.

The Surrealists, led by Breton, were deeply interested in childhood, viewing it as a state closer to the unfiltered subconscious, free from the constraints of adult rationality and logic. Children's games, rhymes, and art were seen as expressions of this primal creativity and imaginative freedom. Roy's dedication to preserving and sharing these "comptines" suggests a similar appreciation for the poetic, irrational, and liberating qualities found in childhood expression. It reflects his pursuit of "spiritual freedom" and aligns with the Surrealist quest to access deeper, less conventional modes of thought and perception, finding the marvelous in unexpected places – in this case, the folk traditions passed down through generations of children.

Connections and Contemporaries

Pierre Roy's career unfolded amidst a constellation of influential artists. His foundational friendship with Giorgio de Chirico was paramount, linking him directly to the pre-Surrealist explorations of the metaphysical. Within the Surrealist movement itself, he interacted with its central figures. While perhaps not as ideologically aligned with the revolutionary fervor of André Breton as some others, he exhibited alongside Max Ernst, known for his pioneering work in collage and frottage; Joan Miró, who developed a unique language of biomorphic signs; and the photographer and object-maker Man Ray.

Roy is often grouped with the more figurative or illusionistic wing of Surrealism, sometimes referred to as Veristic Surrealism. His contemporaries in this vein include the Belgian painter René Magritte, whose work similarly employed realistic techniques to create visual paradoxes and philosophical conundrums; the Spanish master Salvador Dalí, famous for his flamboyant personality and meticulously rendered "hand-painted dream photographs"; the Belgian Paul Delvaux, known for his haunting scenes of nudes and classical architecture bathed in eerie light; and Yves Tanguy, who created desolate, dreamlike landscapes populated by strange, smooth biomorphic forms.

His connection to Dadaism links him to figures like Marcel Duchamp, whose concept of the readymade revolutionized 20th-century art, and Jean Arp (Hans Arp), who worked across Dada and Surrealism, creating biomorphic sculptures and reliefs. While stylistically different, comparing Roy's precise still lifes to those of an artist like Giorgio Morandi, who dedicated his career to the quiet contemplation of simple vessels, highlights Roy's unique Surrealist twist on the genre. His work can also be seen in dialogue with other Magic Realists active in Europe and the Americas during the same period. The influence of Surrealism, carried partly by artists like Roy, would also impact later generations of artists, including American painters like Kay Sage and Dorothea Tanning.

Later Career and Legacy

While Pierre Roy was integral to the early phase of Surrealism, sources suggest his formal association with the core group, known for its strict ideological positions and sometimes tumultuous internal politics under Breton's leadership, may have lessened over time. One snippet mentions he "refused the revolutionary ideology" of the movement, suggesting a potential divergence in political or philosophical outlook, a common occurrence within the group's history.

Regardless of his formal affiliation status in later years, Roy continued to paint and exhibit, maintaining his distinctive style. His participation in the Paris Salons and exhibitions at galleries like Galerie Pierre (as documented in 1928) indicate a sustained professional career. His work continued to explore the themes and techniques he had established, refining his unique blend of realism and the uncanny.

Pierre Roy's legacy lies in his contribution to the diversity of Surrealism and his mastery of a Magic Realist aesthetic. He demonstrated that the Surrealist exploration of the subconscious could be achieved through meticulous control and the subtle manipulation of reality, rather than solely through automatism or abstraction. His paintings offer a quieter, more contemplative form of Surrealism, one that relies on precision, atmosphere, and the poetic resonance of carefully chosen and arranged objects. He remains an important figure for understanding the interplay between realism, Dada, Surrealism, and Magic Realism in the first half of the 20th century, an artist whose work continues to intrigue viewers with its silent, enigmatic beauty.

Conclusion

Pierre Roy was a distinctive voice in 20th-century French art. Emerging from Nantes to become a key participant in the early Parisian Surrealist movement, he developed a highly personal style characterized by the meticulous, realistic depiction of everyday objects arranged in strange and evocative ways. Influenced by Giorgio de Chirico and Dadaism, and closely aligned with Magic Realism, Roy carved out a unique space for himself. His participation in the first Surrealist exhibition and his recognition by critics like André Salmon attest to his early importance. Through works like Danger on the Stairs and numerous enigmatic still lifes, and even through his interest in children's rhymes, Roy explored themes of the subconscious, memory, childhood, and the uncanny lurking beneath the surface of the ordinary. Though perhaps less famous than some of his contemporaries like Dalí or Magritte, Pierre Roy's precisely crafted, quietly disturbing paintings remain a significant contribution to modern art, demonstrating the power of realism when employed in the service of dreams and mystery.