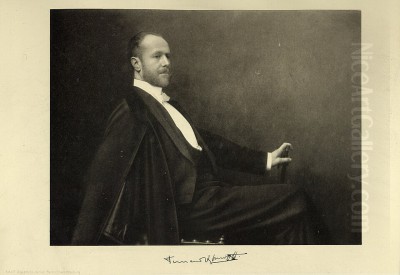

Fernand Edmond Jean Marie Khnopff stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of late nineteenth and early twentieth-century European art. A leading light of Belgian Symbolism, Khnopff was a multifaceted artist – a painter, draughtsman, sculptor, photographer, and occasional writer – whose work delves into the realms of silence, mystery, introspection, and the enigmatic nature of the human psyche. His meticulously crafted images, often imbued with a haunting stillness and psychological depth, continue to fascinate viewers, offering glimpses into a world poised between reality and dream. This exploration delves into the life, work, influences, and enduring legacy of this unique Belgian master.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born on September 12, 1858, in Grembergen, a municipality now part of Dendermonde in East Flanders, Belgium, Fernand Khnopff hailed from a prosperous and well-established bourgeois family. His lineage was steeped in law; generations of Khnopffs had served as lawyers or judges. This background provided him with a comfortable upbringing but also set expectations he would ultimately diverge from. A significant part of his childhood was spent in Bruges, a city whose medieval architecture, quiet canals, and pervasive sense of history would leave an indelible mark on his artistic sensibility, later becoming a recurring motif in his work, symbolizing memory and melancholy.

The family eventually relocated to Brussels, where Khnopff initially pursued a path aligned with family tradition, enrolling in law school at the Free University of Brussels. However, his passion lay elsewhere. He simultaneously attended classes at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, finding the traditional academic training stifling. More influential during this period was his encounter with the work of Xavier Mellery, a Belgian painter known for his evocative depictions of interiors and silent life, whose emphasis on intimacy and the soul of inanimate objects resonated with Khnopff.

A pivotal journey to Paris in 1877 further solidified his artistic direction. There, he discovered the works of Eugène Delacroix, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, and Gustave Moreau. Moreau, in particular, with his richly detailed paintings exploring mythological and biblical themes laden with symbolism, made a profound impression. Khnopff was also exposed to the works of the English Pre-Raphaelites, likely through reproductions or exhibitions. The meticulous technique, literary inspiration, and focus on intense emotional states found in artists like Edward Burne-Jones and Dante Gabriel Rossetti deeply appealed to him and would significantly shape his developing style.

The Emergence of a Symbolist Vision

Abandoning his law studies, Khnopff fully committed himself to art. He quickly gained recognition within the Belgian avant-garde circles. In 1883, he became one of the founding members of the influential group Les Vingt (Les XX), or The Twenty. This Brussels-based collective, active until 1893, was crucial in promoting modern art in Belgium, organizing annual exhibitions that showcased not only its members but also leading international artists. Les XX became a hub for Post-Impressionism, Symbolism, and Art Nouveau, fostering a climate of artistic innovation and exchange.

Within Les XX, Khnopff exhibited alongside prominent Belgian artists such as James Ensor, Théo van Rysselberghe, and Félicien Rops, as well as international figures invited to participate, including Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Auguste Rodin, James McNeill Whistler, and later, Paul Gauguin. Khnopff's involvement placed him at the forefront of contemporary artistic developments and provided a platform for his unique vision.

His early works began to display the hallmarks of his mature style. Listening to Chopin (1883) already hints at the introspective mood and refined atmosphere characteristic of his oeuvre. The Portrait of Jeanne Kéfer (1885) is a masterful example of his ability to convey psychological depth, depicting a young girl standing before a closed door, holding a gloved hand, her gaze direct yet distant, suggesting a world of inner thoughts shielded from the viewer. The composition, with its careful framing and subtle symbolism, exemplifies his move towards Symbolist concerns.

The Enigmatic Woman: Marguerite and the Ideal

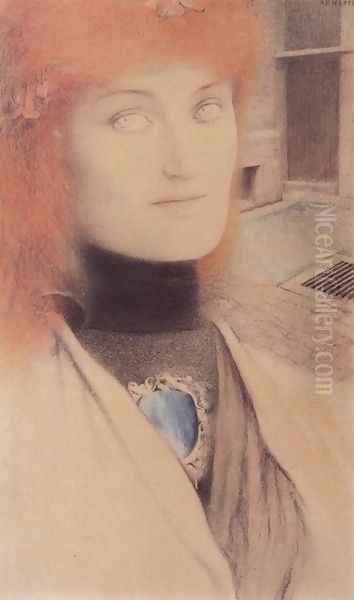

Central to Khnopff's art is the recurring figure of the woman, often depicted as enigmatic, aloof, and embodying complex psychological states. His primary model and muse was his own sister, Marguerite. She appears in numerous paintings, drawings, and photographs, often embodying an ideal of androgynous beauty, introspection, and untouchable purity. The relationship between brother and sister, seemingly close yet marked by a certain artistic distance, fueled much of his most iconic imagery.

Memories (also known as Lawn Tennis) (1889) is a key work featuring Marguerite. It presents seven identical figures of her, dressed for tennis, arranged across a lawn in a dreamlike, non-narrative composition. The repetition and frozen poses create an atmosphere of suspended time and internalized reflection, suggesting the fragmented and persistent nature of memory itself. The work eschews conventional portraiture, instead using Marguerite's image to explore themes of the self, time, and the inner world.

Another famous work inspired by Marguerite and reflecting Khnopff's literary interests is I Lock My Door Upon Myself (1891). The title is taken directly from a poem by the English poet Christina Rossetti, sister of the Pre-Raphaelite painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti. The painting depicts a contemplative female figure, closely resembling Marguerite, in a confined, richly decorated interior. She gazes out, perhaps inward, surrounded by symbolic objects: lilies representing purity, a sculpted head evoking Hypnos (the Greek god of sleep), and fragmented views suggesting a separation from the outside world. It is a powerful image of self-imposed isolation and introspection.

Silence, Solitude, and Introspection

A profound sense of silence permeates Khnopff's work. His figures often seem lost in thought, inhabiting spaces that are both physically real and psychologically charged. He masterfully used composition, muted color palettes (often dominated by blues, greys, and violets), and precise rendering to create atmospheres of stillness and contemplation. This focus on the inner life, on unspoken thoughts and emotions, aligns perfectly with the core tenets of Symbolism, which sought to express subjective experiences and ideas rather than objective reality.

His interiors are frequently depicted as sanctuaries or prisons of the self. Windows and mirrors appear regularly, but often they do not offer escape or clear reflection. Instead, they might show obscured views or reflect back the interior space, reinforcing the sense of enclosure and the primacy of the inner world. This contrasts sharply with Impressionist paintings, which often celebrated light and the external world. Khnopff directs the viewer's attention inward, towards the complexities of the psyche.

The theme of solitude is palpable. Even when multiple figures are present, as in Memories, they often seem isolated from one another, each contained within their own mental space. This reflects a fin-de-siècle sensibility, an awareness of alienation and the difficulty of true communication that resonated with many artists and writers of the period, such as the poet Stéphane Mallarmé, whose work Khnopff admired.

Bruges: City of Memory and Melancholy

Khnopff's childhood connection to Bruges found artistic expression in a series of works depicting the "dead city." Bruges, with its preserved medieval architecture and quiet canals, had become a symbol of decline and nostalgia in the late 19th century, famously captured in Georges Rodenbach's novel Bruges-la-Morte (Bruges the Dead) of 1892. Khnopff shared this fascination with the city's melancholic beauty and its power to evoke the past.

His depictions of Bruges are rarely straightforward cityscapes. Instead, he focused on specific views, often deserted canals reflecting gabled houses under muted light, emphasizing the stillness and silence of the city. These works, such as Secret-Reflet (Secret-Reflection), transform the physical location into a symbol of memory, loss, and the persistence of the past within the present. The reflective water surfaces become metaphors for the mind mirroring its own thoughts and recollections. Khnopff's Bruges is less a place and more a state of mind, a landscape of the soul.

Myth, Allegory, and the Sphinx

Like many Symbolists, Khnopff drew upon myth and allegory to explore complex themes. He was particularly drawn to figures that embodied mystery, duality, and the power of the feminine, often interpreted through a fin-de-siècle lens that emphasized the femme fatale or the enigmatic woman.

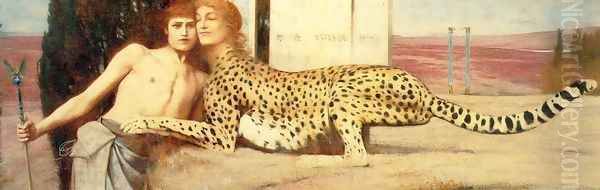

His most famous work in this vein is undoubtedly The Caresses (also known as Art, or The Sphinx) (1896). This iconic painting depicts an androgynous youth, often identified as Oedipus, receiving the caress of a sphinx with the body of a cheetah or leopard and the head of a woman – a face strikingly similar to Marguerite's. The background features a stylized landscape with classical columns and cypress trees under a deep blue sky. The image is charged with ambiguity: is it a moment of tenderness, seduction, or impending danger? The sphinx, traditionally a symbol of riddles and destiny, here embodies a complex fusion of intellect, animal instinct, and alluring yet potentially destructive femininity. The work is often compared to Gustave Moreau's treatment of similar themes but possesses Khnopff's unique blend of cool precision and unsettling intimacy.

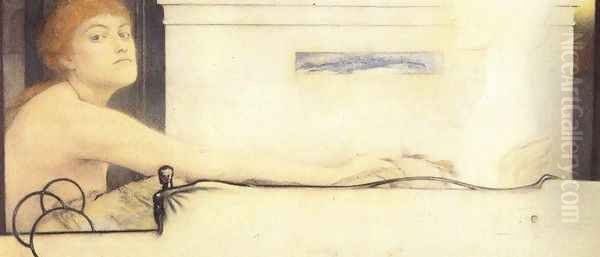

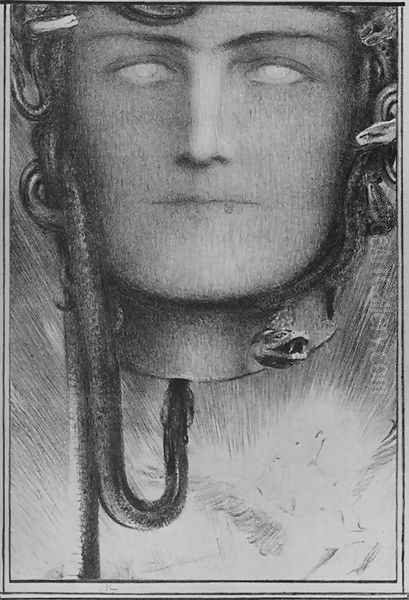

Another exploration of myth is Sleeping Medusa (1896). Khnopff subverts the traditional terrifying image of the Gorgon. Instead of snakes, her hair seems composed of delicate, wing-like forms, and her face, again reminiscent of Marguerite, is serene in sleep. The potential danger is internalized, hidden beneath a calm exterior, suggesting the hidden depths and perhaps dormant power within the psyche. This reinterpretation is typical of Khnopff's approach, favoring psychological nuance over overt narrative or horror.

Artistic Techniques and Stylistic Hallmarks

Khnopff's technical mastery is undeniable. He worked primarily in oil and pastel, often achieving a smooth, highly finished surface that emphasizes the precision of his drawing. His draftsmanship was exceptional, allowing him to render details with almost photographic clarity. This meticulous realism, however, was always employed in the service of creating a non-realistic, dreamlike atmosphere. The juxtaposition of sharp focus with ambiguous settings or symbolic elements is key to the unsettling power of his work.

His compositions are carefully constructed, often employing unusual cropping, framing devices (like the prominent foreground elements in Portrait of Jeanne Kéfer), and flattened perspectives influenced by Japanese prints, which were highly fashionable in Europe at the time. This formal control contributes to the sense of stillness and deliberate arrangement in his pictures.

His use of color was subtle and evocative. He favored restricted palettes, often dominated by cool tones – blues, greys, mauves, pale yellows – which enhance the melancholic and introspective mood. Occasional flashes of stronger color, like the orange in the sphinx's fur or details in costume, stand out dramatically against the muted backgrounds. Light in his paintings is often diffuse and soft, contributing to the dreamlike quality and avoiding harsh contrasts.

Photography as an Integral Tool

Khnopff was an early adopter of photography, not merely as a preparatory aid but as an integral part of his creative process. He took numerous photographs, particularly of his sister Marguerite, often posing her in specific attitudes or costumes that would later appear in his paintings and drawings. These photographs, rediscovered later, reveal the extent to which his painted images were based on carefully staged photographic sources.

His use of photography went beyond simple reference. He sometimes drew or painted directly onto photographic prints, blurring the lines between the mechanical reproduction and the artist's hand. This practice highlights his interest in the interplay between reality and representation, and the way images mediate our perception of the world. The photographs themselves, particularly those of Marguerite, possess a haunting quality and artistic merit in their own right, sharing the enigmatic atmosphere of his finished paintings. They demonstrate his control over pose, lighting, and composition across different media.

Connections to Literature and the Written Word

Literature was a constant source of inspiration for Khnopff. He was deeply read in contemporary Symbolist literature, particularly the works of French poets like Stéphane Mallarmé and Paul Verlaine, whose emphasis on suggestion, mood, and musicality paralleled his own artistic aims. His connection to the English Pre-Raphaelites extended to their literary counterparts, most notably Christina Rossetti, as seen in I Lock My Door Upon Myself. He also admired the work of Gustave Flaubert.

Khnopff was also associated with Joséphin Péladan, the eccentric French writer and occultist who founded the Salons de la Rose + Croix in Paris in the 1890s. These exhibitions aimed to promote a mystical, idealist, and anti-materialist form of Symbolist art. Khnopff exhibited at the first Salon in 1892, aligning himself with its rejection of realism and Impressionism in favor of spiritual and symbolic content. While he maintained some distance from Péladan's more dogmatic pronouncements, the association further cemented his position within the international Symbolist movement.

Beyond being inspired by literature, Khnopff occasionally wrote art criticism and articles himself, contributing to journals like The Studio, an influential British art magazine. This demonstrates his intellectual engagement with the art world and his ability to articulate his own aesthetic principles.

International Recognition and the Vienna Secession

Khnopff's reputation extended well beyond Belgium. He exhibited regularly in Paris, London, Munich, and Vienna, gaining international acclaim. His work was particularly well-received in Vienna, where Symbolism found fertile ground. He was invited to exhibit at the first Vienna Secession exhibition in 1898, a landmark event organized by artists seeking to break away from academic conservatism, including Gustav Klimt, Koloman Moser, and Josef Hoffmann.

Khnopff's contribution was significant, featuring prominently displayed works that deeply impressed the Viennese artists. His refined aesthetic, psychological depth, and synthesis of influences resonated strongly with the aims of the Secessionists. Gustav Klimt, in particular, shows Khnopff's influence in certain works from this period, notably in the elongated formats, decorative elements, and enigmatic female figures found in his own paintings. Khnopff became a corresponding member of the Vienna Secession, solidifying his link with this crucial Central European avant-garde movement. His success abroad was recognized at home; he was awarded the Order of Leopold, a prestigious Belgian honor.

The Villa Khnopff: A Gesamtkunstwerk

Around 1900, Khnopff designed and built his own house and studio in Brussels (specifically in the Avenue des Courses in the municipality of Ixelles). This was not merely a dwelling but an extension of his artistic persona and aesthetic ideals, conceived as a Gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art. The Villa Khnopff was a highly personal sanctuary, designed to facilitate introspection and protect him from the outside world.

The exterior was relatively austere, but the interior was meticulously planned and decorated according to his specific tastes. It featured rooms painted in symbolic colors (white, blue, gold), carefully placed objects, altars dedicated to Hypnos (Sleep), and strategically positioned mirrors and windows that controlled light and views. The studio itself was the heart of the house, a space dedicated to creation. The Villa embodied his ideals of refinement, symbolism, and self-containment. Sadly, the house was demolished after his death, but photographs and descriptions remain, offering insight into his immersive approach to art and life.

Sculpture, Decorative Arts, and Stage Design

While primarily known as a painter, Khnopff's artistic activities were diverse. He produced a small but significant body of sculptural work, often exploring similar themes to his paintings. His masks and busts, sometimes incorporating materials like ivory and bronze, possess the same enigmatic quality and refined finish as his two-dimensional works. Vivien (c. 1896), a colored plaster bust, exemplifies his sculptural approach, capturing a sense of mystery and idealized beauty.

Reflecting the Art Nouveau and Symbolist interest in breaking down barriers between fine and applied arts, Khnopff also engaged in decorative projects and design. He created illustrations for books, designed posters, and even contributed designs for costumes and stage sets, particularly for the Théâtre de la Monnaie in Brussels. This involvement in theatre aligns with the Symbolist interest in drama as a vehicle for exploring deeper psychological and spiritual themes, seen also in the work of contemporaries like Maurice Maeterlinck.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Fernand Khnopff continued to work and exhibit throughout the early 20th century, though his style remained largely consistent, rooted in the Symbolist aesthetic he had mastered. He remained a respected figure in the Belgian art world but perhaps somewhat detached from the rapidly evolving currents of modernism like Fauvism and Cubism. He died in Brussels on November 12, 1921.

Khnopff's legacy is significant. He is considered, alongside James Ensor, one of the most important Belgian artists of his generation and a key figure in international Symbolism. His unique blend of meticulous realism, psychological depth, and enigmatic symbolism created a distinctive and influential body of work.

His influence can be seen in the work of the Vienna Secession artists, particularly Klimt. Later, his dreamlike imagery, juxtaposition of the familiar and the strange, and focus on the subconscious resonated with the Surrealists. Belgian Surrealists like René Magritte and Paul Delvaux, while developing their own distinct styles, arguably inherited Khnopff's penchant for mystery, silence, and the exploration of the inner world presented with startling clarity. His work continues to be studied and admired for its technical brilliance, its haunting beauty, and its profound exploration of the modern psyche. He stands with other great Symbolists like Odilon Redon, Arnold Böcklin, Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, and fellow Belgian Jean Delville as an artist who sought to make the invisible visible, mapping the subtle and often unsettling landscapes of the soul.

Conclusion: The Master of Silence

Fernand Khnopff carved a unique path through the complex artistic landscape of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Rooted in the Symbolist movement, he developed a highly personal visual language characterized by technical precision, psychological intensity, and an aura of pervasive mystery. Through his paintings, drawings, sculptures, and photographs, he explored themes of memory, introspection, silence, and the enigmatic nature of identity, often using his sister Marguerite as a recurring motif for an idealized, untouchable femininity. His connections with Les XX, the Salons de la Rose + Croix, and the Vienna Secession placed him at the heart of European avant-garde developments, while his self-designed Villa stood as a testament to his immersive aesthetic philosophy. Khnopff remains a compelling figure, an artist whose meticulously crafted surfaces conceal depths of meaning, inviting viewers into a silent, contemplative world that continues to echo in the corridors of modern art history.