Gabriel Cornelius von Max stands as a fascinating and somewhat enigmatic figure in the landscape of late 19th and early 20th-century European art. Born in Prague, then part of the Austrian Empire, on August 23, 1840, and working primarily in Munich until his death on November 24, 1915, Max navigated a unique path that intertwined academic tradition with deeply personal explorations of mysticism, spiritualism, Darwinian science, and the burgeoning field of psychology. His work, often characterized by its technical polish yet unsettling subject matter, offers a compelling window into the intellectual and cultural currents of his time, bridging the gap between Romanticism, Realism, and the emerging Symbolist movement.

An artist deeply invested in the unseen, the subconscious, and the connections between humanity and the natural world, Max produced a body of work that continues to intrigue and provoke. From haunting depictions of martyrs and mystics to his peculiar and insightful paintings of monkeys, his art challenges easy categorization. He was a product of rigorous academic training yet constantly pushed against its boundaries, seeking to express the profound mysteries of life, death, and consciousness. This exploration delves into the life, work, influences, and legacy of this Austrian-born painter who became a significant, if sometimes overlooked, presence in the German art scene.

Early Life and Academic Formation

Gabriel Max's artistic inclinations were perhaps inherited. He was the son of the respected Prague sculptor Josef Max and Anna Schumann. Growing up in an artistic household likely fostered his early interest in the visual arts. His formal training began in his birth city at the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, where he studied from 1855 to 1858. During this period, he would have been exposed to the prevailing academic styles, likely under instructors such as Eduard von Engerth, focusing on drawing, composition, and historical themes.

Seeking broader horizons, Max moved to the imperial capital, Vienna, to continue his studies at the prestigious Vienna Academy of Fine Arts. There, he encountered a different set of influences, studying under prominent artists including the history painter Karl von Blaas, Karl Mayer, Christian Ruben, and Carl Wurzinger. The Vienna Academy, while still rooted in academic tradition, was a vibrant center, and these years would have further honed his technical skills and exposed him to the rich artistic heritage of the Habsburg Empire, including its strong Catholic traditions which sometimes surfaced in his later religious works, albeit transformed through a mystical lens.

The most decisive phase of his academic development, however, occurred when he moved to Munich in 1863. He enrolled at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts, a leading institution in the German-speaking world, and joined the master class of Carl Theodor von Piloty in 1863, studying there until 1867. Piloty was a towering figure in German art, renowned for his large-scale historical paintings executed with dramatic flair and meticulous detail. Studying under Piloty placed Max at the heart of the influential Munich School, known for its painterly realism and often dark palettes. This training provided Max with the technical mastery, particularly in rendering figures and creating dramatic compositions, that would underpin his entire career.

Munich, Artistic Breakthrough, and Early Style

Munich became Max's permanent base. In 1869, he established his own independent studio, signaling his readiness to forge his own artistic path. His time at the Academy under Piloty had not only equipped him with skills but also connected him with a network of talented contemporaries. He formed significant friendships with fellow students who would also achieve fame, notably the flamboyant historical and decorative painter Hans Makart and the genre painter Franz Defregger. Through these connections, he likely also came into contact with other key figures of the Munich art scene, such as the leading portraitist Franz von Lenbach. This environment was crucial for his development and integration into the city's artistic life.

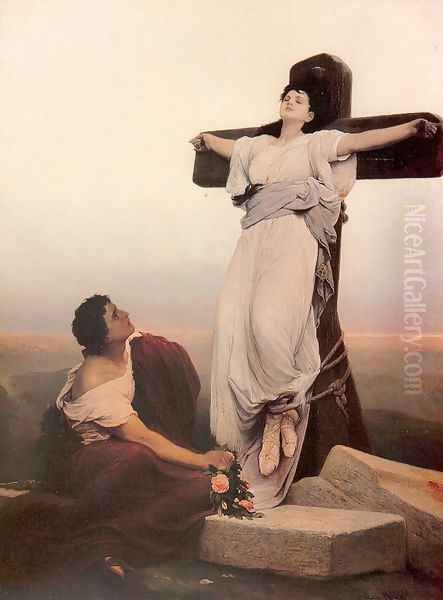

Max's breakthrough came relatively early in his independent career with the painting The Christian Martyr (also known as Martyr on the Cross), completed in 1867 while still technically under Piloty's influence but exhibited to great acclaim shortly after. This work, depicting a young female martyr expiring peacefully on a cross by the seashore, exemplified the technical polish of the Piloty school but significantly diverged in its emotional tone. Instead of focusing on the historical drama or physical agony typical of Piloty's output, Max imbued the scene with a sense of quiet ecstasy and spiritual transcendence. It transformed a traditional depiction of suffering into a symbolist exploration of religious mysticism and the boundary between life and death.

This painting established key elements of Max's early style: a preference for dark, atmospheric palettes, a smooth, detailed finish, and a focus on psychologically intense, often melancholic or spiritual themes, frequently centered on female figures. While indebted to his academic training, The Christian Martyr already hinted at the more personal and unconventional directions his art would take, moving away from straightforward historical narrative towards allegory and psychological exploration. The success of this work brought him considerable attention and marked the beginning of his reputation as a painter of profound, if often somber, subjects.

Thematic Evolution: Mysticism and the Supernatural

While historical and religious subjects remained part of his repertoire, Gabriel von Max increasingly gravitated towards themes rooted in mysticism, spiritualism, and the exploration of altered states of consciousness. This shift reflected both his personal interests and the wider cultural fascination with the occult and parapsychology in the late 19th century. He became deeply involved in the spiritualist movement, which sought evidence of life after death and communication with spirits through mediums.

Max's interest was not merely theoretical; he actively participated in séances and experiments related to paranormal phenomena. He developed connections with prominent figures in the field, such as the philosopher and psychical researcher Carl du Prel and the physician and parapsychologist Albert von Schrenck-Notzing. These associations provided him with subject matter and informed his attempts to visually represent experiences that lay beyond the realm of ordinary perception. He sought to depict the invisible, the ethereal, and the psychological states associated with mystical or mediumistic trance.

This fascination manifested in works like The Ecstatic Virgin Anna Katharina Emmerich (c. 1885), depicting the German mystic known for her visions and stigmata. Max portrays her not in a conventional religious manner, but as a figure lost in an internal, ecstatic experience, highlighting the psychological rather than purely devotional aspect. Another notable work reflecting these interests is Spirit Greeting (Geistergruß), which directly visualizes a spectral presence, attempting to capture the uncanny nature of spiritualist encounters. His paintings often feature figures with closed or upturned eyes, suggesting an inward focus or connection to another realm, characteristic of Symbolist art's emphasis on subjective experience over objective reality. Max also became a member of the Theosophical Society, further indicating his commitment to exploring esoteric philosophies.

Science, Darwinism, and Anthropology

Parallel to his immersion in mysticism, Gabriel von Max cultivated a profound and equally serious interest in the natural sciences, particularly Darwinian evolutionary theory, anthropology, and prehistory. This seemingly contradictory pairing of interests – the spiritual and the scientific – was characteristic of the era, a time when many intellectuals grappled with the implications of new scientific discoveries for traditional beliefs about humanity's place in the universe. Max saw no inherent conflict, exploring both realms with equal curiosity.

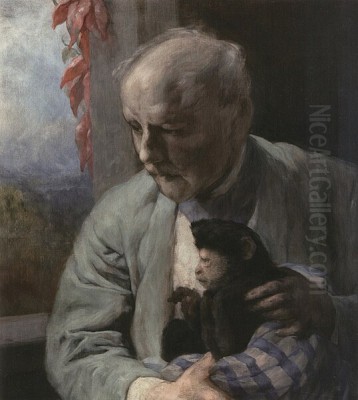

His engagement with Darwinism found its most unique expression in his numerous paintings of monkeys. These were not mere animal studies; Max kept monkeys in a large enclosure at his home, observing them closely. He depicted them with remarkable empathy and psychological insight, often anthropomorphizing them to explore themes of consciousness, emotion, and the relationship between humans and other primates. Works like Monkeys as Art Critics (1889) use the animals for satirical purposes, humorously critiquing the art establishment. Others seem to ponder the evolutionary links highlighted by Darwin, presenting monkeys in thoughtful or melancholic poses that suggest an inner life.

Max's scientific interests extended to anthropology and ethnography. He amassed a significant private collection of prehistoric, anthropological, and ethnographic artifacts from around the world. This vast collection, numbering tens of thousands of items including numerous skulls, demonstrated a deep engagement with human origins and cultural diversity. After his death, this important collection found a permanent home in the Reiss-Engelhorn Museums in Mannheim, Germany, where it remains a testament to his wide-ranging intellect. His friendship with the prominent German biologist and fervent proponent of Darwinism, Ernst Haeckel, further underscores the seriousness of his scientific pursuits. They reportedly discussed theories about human evolution and shared an interest in understanding life's biological underpinnings. This scientific curiosity also informed works like The Anatomist (1869), a stark and unsettling depiction of a young woman's corpse on a dissection table, confronting viewers with the physical realities of death and scientific inquiry.

Style and Technique

Gabriel von Max's artistic style is a complex blend of influences and personal innovations. Fundamentally, his technique was rooted in the academic realism of the Munich School, particularly the meticulous rendering and tonal mastery associated with Piloty. He possessed a remarkable ability to depict human anatomy, textures, and facial expressions with precision. However, he employed this technical skill not merely for realistic representation but to convey psychological depth and atmospheric mood, aligning him more closely with the aims of Symbolism.

His use of color evolved over his career. Early works, like The Christian Martyr, are characterized by dark, somber palettes, utilizing chiaroscuro to create dramatic and often melancholic effects. From the late 1870s onwards, his palette generally lightened, incorporating softer tones and a more nuanced use of color, although a sense of mystery and introspection often remained. His handling of light was crucial in creating the desired atmosphere, whether it was the ethereal glow surrounding a mystic or the stark illumination of a scientific setting.

Max's compositions are typically carefully constructed, often focusing on one or two figures in a way that emphasizes their psychological state. He frequently depicted women, often portrayed as sensitive, vulnerable, melancholic, or in states of trance or near-death. While reflecting some 19th-century tropes about female sensitivity and fragility, his portrayals often possess a psychological intensity that transcends mere stereotype, inviting contemplation on inner experience. His work shares affinities with the broader Symbolist movement's interest in dreams, emotions, and the inner world, and his refined aesthetic and sometimes decorative qualities can be seen as prefiguring elements of Art Nouveau or Jugendstil, particularly in his sensitive rendering of figures and surfaces. He bridged the gap between the detailed finish of academic art and the evocative, subjective content of Symbolism.

Academic Career and Later Life

Gabriel von Max's reputation earned him a prestigious position as a Professor of History Painting at the Munich Academy of Fine Arts, a role he held from 1879 to 1883. This appointment acknowledged his standing within the Munich art world and his mastery of the technical aspects of painting, particularly figure painting and historical composition, even as his thematic interests diverged from traditional history painting. However, his tenure as a professor was relatively short. Reports suggest he resigned due to a decline in lucrative commissions or perhaps a desire to focus more fully on his increasingly personal and unconventional artistic explorations.

Despite leaving his official academic post, Max remained a respected figure. In 1900, his contributions to art were recognized when he was ennobled by Prince Regent Luitpold of Bavaria, allowing him to use the title "von Max." He continued to paint and pursue his diverse interests in science and spiritualism from his base in Munich and his summer residence near Lake Starnberg. He maintained his connections within the artistic and intellectual communities, including his friendship with Ernst Haeckel and his involvement with esoteric circles.

His later years saw him continue to explore his characteristic themes, though perhaps with less public visibility than in his earlier career peak. The rise of modern art movements like Expressionism and abstraction began to shift artistic tastes away from the blend of realism and symbolism that characterized Max's work. He passed away in Munich on November 24, 1915, at the age of 75, leaving behind a substantial and highly distinctive body of work, as well as his significant scientific collections.

Art Historical Significance and Legacy

Evaluating Gabriel von Max's position in art history reveals a complex picture. During his lifetime, particularly in the 1870s and 1880s, he was a highly regarded and successful artist within the Munich School. His technical skill was undeniable, and his unique thematic blend attracted considerable attention, even fascination. He can be seen as a significant transitional figure, emerging from the historicism of the Piloty school and evolving towards the subjective and psychological concerns of Symbolism. His work clearly prefigures aspects of the Munich Secession, a movement founded in 1892 that broke away from the conservative academy establishment, partly through the influence of artists like Albert von Keller, with whom Max shared an interest in psychological and mystical themes.

However, Max's reputation waned considerably in the early 20th century. The advent of modernism led to a reevaluation of 19th-century academic and Symbolist art, much of which was dismissed as sentimental, illustrative, or overly literary. Max's work, with its smooth finish and sometimes morbid or esoteric subject matter, was susceptible to being labeled as "kitsch" or simply falling out of fashion. His unique blend of science and spiritualism might also have seemed contradictory or eccentric to later generations focused on formal innovation. Consequently, for much of the 20th century, he was relatively neglected by mainstream art history.

In recent decades, there has been a resurgence of interest in Symbolism and other aspects of 19th-century art that were previously overlooked. Scholars and curators have begun to re-examine Gabriel von Max's work, recognizing its technical brilliance, psychological depth, and its importance as a reflection of the intellectual ferment of his time. His engagement with Darwinism, parapsychology, and anthropology makes him a particularly interesting case study for understanding the intersections of art, science, and belief in the late 19th century. His monkey paintings, once perhaps seen as mere curiosities, are now appreciated for their insight and originality. While perhaps not a radical innovator in the mold of the Impressionists or early modernists, Max stands as a master technician who used his skills to explore unconventional and deeply personal territory, leaving a legacy that is both haunting and intellectually stimulating. He remains an important, if sometimes challenging, figure for understanding the diverse currents of European art between Romanticism and Modernism.

Conclusion

Gabriel von Max was an artist of profound contradictions and compelling depth. Trained in the rigorous academic traditions of Prague, Vienna, and Munich under masters like Carl Theodor von Piloty, he achieved technical mastery but directed it towards ends far removed from conventional history painting. His canvases became arenas for exploring the liminal spaces between life and death, science and spirit, human and animal. His fascination with mysticism, spiritualism, and the occult coexisted with a deep engagement with Darwinian evolution and anthropological inquiry, interests reflected in his haunting depictions of saints, martyrs, mediums, and his uniquely empathetic portraits of monkeys.

Connected to key figures like Hans Makart, Franz Defregger, Franz von Lenbach, and Ernst Haeckel, Max was embedded in the intellectual life of his time, yet his artistic vision remained intensely personal. Though highly successful in his prime, his work fell into relative obscurity before experiencing a renewed appreciation in recent times. Today, Gabriel von Max is recognized not only for his technical prowess but for his courage in tackling complex, often unsettling themes that probed the psychological and spiritual anxieties of the late 19th century. His art serves as a powerful reminder of a period when the boundaries between disciplines were more fluid, and artists dared to venture into the uncharted territories of both the psyche and the cosmos. His legacy is that of a painter who masterfully rendered the visible world while constantly striving to give form to the unseen.