Carlos Schwabe stands as a pivotal yet often underappreciated figure in the Symbolist art movement that flourished across Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. A German-born Swiss artist, Schwabe's work is characterized by its profound mysticism, meticulous detail, and exploration of themes such as life, death, spirituality, and the ideal. His paintings and illustrations, often imbued with an ethereal, dreamlike quality, offer a unique window into the anxieties and aspirations of the fin-de-siècle. This article delves into the life, art, and enduring legacy of Carlos Schwabe, examining his education, stylistic development, key works, and his connections within the vibrant artistic milieu of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

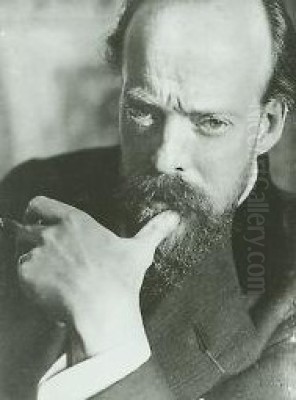

Emil-Maria-Carl Schwabe, who would later be known as Carlos Schwabe, was born on July 21, 1866, in Altona, then a Danish-controlled city near Hamburg, Germany, which later became part of Prussia. His family background was modest. Shortly after his birth, his family relocated to Geneva, Switzerland, a city that would play a crucial role in his early development and where he would eventually acquire Swiss citizenship. It was in Geneva that Schwabe's artistic inclinations began to take shape.

He enrolled at the École des Arts Industriels (School of Industrial Arts), often referred to as the École des Arts Décoratifs, in Geneva. This institution, focused on applied arts, provided him with a strong foundation in drawing and design. During his studies, from approximately 1880 to 1884, he was a student of Joseph Mittey, a professor known for his work in decorative painting and ceramics. Mittey's instruction emphasized precise observation of nature and a mastery of line, skills that would become hallmarks of Schwabe's mature style. This early training in the decorative arts likely contributed to the meticulous detail and ornamental qualities found in many of his later Symbolist works. Even at this stage, Schwabe was reportedly drawn to visionary subjects, hinting at the direction his art would eventually take.

The Parisian Crucible: Embracing Symbolism

In 1884, at the age of eighteen, Carlos Schwabe made the pivotal decision to move to Paris, the undisputed epicenter of the art world at the time. This move immersed him in a dynamic and intellectually charged environment where new artistic ideas were constantly challenging established conventions. Paris was a melting pot of artistic movements, but it was Symbolism that resonated most deeply with Schwabe's temperament and artistic vision.

Symbolism emerged as a reaction against the prevailing trends of Realism and Naturalism, which focused on objective depictions of the observable world, and Impressionism, which emphasized fleeting sensory perceptions. Symbolist artists, writers, and poets sought to explore the inner world of dreams, emotions, ideas, and spirituality. They aimed to evoke rather than describe, using symbols to suggest deeper, often mystical, truths. Key figures who were already shaping the Symbolist landscape included Gustave Moreau, with his opulent and enigmatic mythological scenes; Pierre Puvis de Chavannes, known for his serene and allegorical murals; and Odilon Redon, whose "noirs" and later vibrant pastels delved into the realms of dreams and the subconscious.

Schwabe quickly integrated into these circles. He was particularly drawn to the literary Symbolists, and his early career in Paris saw him gain recognition primarily as an illustrator. His ability to translate complex literary themes into compelling visual narratives made him a sought-after collaborator for authors exploring Symbolist ideas. This period was crucial for Schwabe, as he absorbed the intellectual currents of the time and began to forge his distinctive artistic identity within the broader Symbolist movement.

Schwabe's Artistic Signature: Style and Technique

Carlos Schwabe developed a highly personal and recognizable artistic style, characterized by its meticulous draftsmanship, ethereal atmosphere, and rich symbolic content. His technical proficiency, honed during his studies in Geneva, was evident in the precision of his lines and the delicate rendering of forms. He was particularly adept with watercolor, a medium he used to create luminous and dreamlike effects, but he also worked in oils and produced numerous drawings and designs.

A defining feature of Schwabe's style is its linearity. His compositions often feature elegant, flowing lines reminiscent of early Renaissance masters like Sandro Botticelli and Andrea Mantegna, as well as Northern Renaissance artists such as Albrecht Dürer. This emphasis on line gives his figures a certain clarity and grace, even when they are part of complex, otherworldly scenes. There is also a discernible influence from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, particularly artists like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Edward Burne-Jones, in his depiction of idealized female figures, his attention to detail, and his interest in medieval and mythological themes.

Schwabe's use of color was often symbolic rather than naturalistic. He could employ a muted, almost monochromatic palette to evoke a sense of melancholy or spirituality, or he could use vibrant, jewel-like colors to highlight specific symbolic elements or create a heightened emotional impact. His compositions are frequently populated by elongated, graceful figures, often winged or angelic, set against stylized landscapes or architectural backdrops. These figures, whether representing angels, allegorical personifications, or mythological beings, convey a sense of otherworldly beauty and spiritual longing. The overall effect is one of intense idealism, a striving for a reality beyond the mundane, which is central to the Symbolist ethos.

Thematic Constellations in Schwabe's Oeuvre

The thematic concerns in Carlos Schwabe's art are deeply rooted in Symbolist preoccupations with the inner life, spirituality, and the great mysteries of existence. Death is a recurring and central theme, but Schwabe often portrays it not as a terrifying end but as a transformative passage, frequently personified by serene, angelic figures. His iconic work, The Death of the Gravedigger (1895-1900), exemplifies this, where a winged angel gently guides the soul of an old gravedigger upwards, away from a snow-covered, desolate landscape. This portrayal emphasizes spiritual release and the transcendence of earthly suffering.

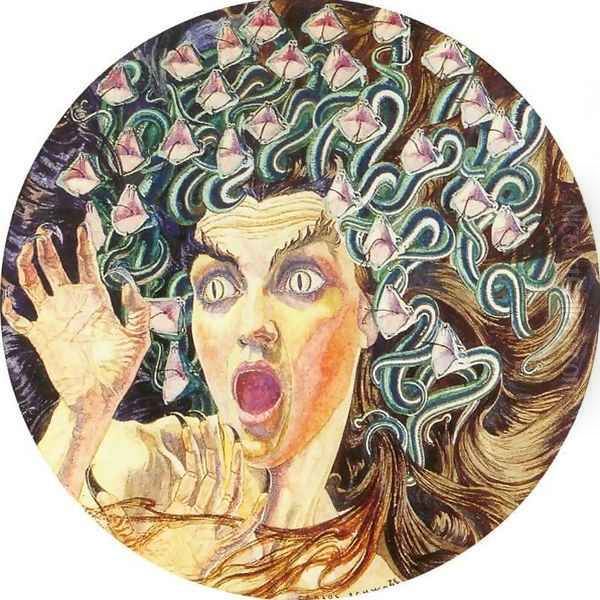

The feminine figure is another dominant motif in Schwabe's work. He depicted women in various guises: as ethereal virgins, pure and innocent, embodying spiritual ideals (a common Symbolist trope of the femme fragile); as powerful, sometimes enigmatic, mythological figures like Medusa; or as personifications of abstract concepts like pain (La Douleur) or hope (L'Angelo di speranza). These figures are rarely mere portraits; they are carriers of symbolic meaning, often reflecting contemporary anxieties and ideals about femininity, spirituality, and the human condition.

Schwabe's art is also rich in Christian iconography and mystical symbolism, though often interpreted through a personal, esoteric lens. Angels, lilies (symbolizing purity), roses (symbolizing love or martyrdom), and other religious symbols appear frequently. He was associated with Joséphin Péladan's Salon de la Rose+Croix, an esoteric Rosicrucian-inspired Symbolist art salon that promoted art with spiritual, mystical, and idealistic themes. Schwabe designed the poster for the first Salon de la Rose+Croix in 1892, a work that itself became an emblem of the movement, depicting an ascent towards an ideal, guided by faith and purity. This connection underscores his deep engagement with the spiritual and occult currents of Symbolism.

Nature, too, plays a significant symbolic role in his work. Landscapes are rarely just backdrops; they are imbued with emotional and spiritual significance. Water, mountains, and celestial bodies often appear, contributing to the overall mystical atmosphere of his compositions.

Masterpieces of Illustration and Painting

Carlos Schwabe's reputation was significantly built upon his exceptional work as an illustrator. He possessed a rare talent for visually interpreting complex literary texts, enhancing their meaning through his symbolic imagery. One of his most celebrated achievements in this field was his series of illustrations for Émile Zola's novel Le Rêve (The Dream), published in 1892. Zola's novel, while part of his Naturalist Rougon-Macquart cycle, has strong mystical and dreamlike elements, focusing on the innocent Angélique who lives in a world of religious fantasy. Schwabe's delicate, ethereal illustrations perfectly captured the novel's atmosphere, depicting Angélique's spiritual visions and romantic longings with sensitivity and grace. These illustrations are considered a high point of Symbolist book art.

Another major illustrative project was for Charles Baudelaire's seminal collection of poetry, Les Fleurs du mal (The Flowers of Evil). Illustrating Baudelaire, with his exploration of decadence, sin, and melancholic beauty, presented a different challenge. Schwabe's interpretations, published in 1900, delved into the darker, more sensual, and psychologically complex aspects of Baudelaire's verse, demonstrating his versatility in conveying a wide range of Symbolist themes. His work La Douleur (Pain), also known as The Artist's Grief or The Widower, is sometimes linked to the spirit of Baudelaire, depicting a grieving man comforted by an angel, a poignant image of sorrow and solace.

He also provided illustrations for Maurice Maeterlinck's Symbolist play Pelléas et Mélisande and Catulle Mendès's poetry collection Hésperus. Each of these projects showcased his ability to adapt his style to the specific tone and themes of the literary work, while maintaining his distinctive artistic voice.

Beyond illustrations, Schwabe produced significant paintings. The Death of the Gravedigger, mentioned earlier, is a powerful oil painting that garnered considerable acclaim, including a gold medal at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1900. Medusa (1895) offers a compelling rendition of the mythological figure, emphasizing her tragic and formidable nature. La Vague (The Wave, 1907) is another notable work, depicting a group of female figures enveloped and almost consumed by a massive, stylized wave, a powerful symbol of overwhelming natural forces or perhaps emotional turmoil. His poster for the first Salon de la Rose+Croix (1892) is itself a masterpiece of Symbolist design, depicting two female figures ascending a staircase towards a radiant ideal, with a third figure left behind in despair.

A Nexus of Symbolist Thought: Schwabe and His Contemporaries

Carlos Schwabe was an active participant in the Symbolist movement, and his work developed in dialogue with that of his contemporaries. His involvement with Joséphin Péladan's Salon de la Rose+Croix placed him at the heart of a specific current within Symbolism that emphasized idealism, mysticism, and a rejection of materialism. The Salons de la Rose+Croix, held annually in Paris from 1892 to 1897, were influential showcases for artists who shared these esoteric and spiritual concerns. Schwabe's poster for the inaugural Salon became an iconic image of the movement, and he exhibited alongside other prominent Symbolists such as Jean Delville, Fernand Khnopff, Félicien Rops, and Arnold Böcklin (though Böcklin's involvement was more by association than direct participation).

Schwabe's art shares affinities with several of these artists. Like Jean Delville, he explored themes of spiritual initiation and the ideal. With Fernand Khnopff, he shared an interest in enigmatic female figures and dreamlike atmospheres, though Khnopff's work often possesses a more hermetic and psychologically intense quality. While Félicien Rops delved into more overtly erotic and satanic themes, the underlying Symbolist concern with the hidden forces shaping human existence connects their oeuvres. Arnold Böcklin, a Swiss-German contemporary, though often considered a precursor or independent figure, created powerful mythological landscapes and allegories (like Isle of the Dead) that resonated with the Symbolist mood of introspection and melancholy.

Compared to other leading Symbolists, Schwabe's style maintained a unique balance. He did not quite reach the jewel-like opulence of Gustave Moreau, nor the shadowy, primal depths of Odilon Redon's "noirs." His figures, while idealized, often possess a tender vulnerability that distinguishes them from the more aloof or monumental figures of Puvis de Chavannes. While Edvard Munch, a Scandinavian Symbolist, channeled profound psychological angst and existential dread into his art, Schwabe's work, even when dealing with death or sorrow, often retains a sense of spiritual hope or transcendent beauty.

His meticulous draftsmanship and decorative sensibility also show some parallels with the emerging Art Nouveau style, particularly in his flowing lines and stylized natural forms. Artists like Alphonse Mucha, while more central to Art Nouveau, shared with Schwabe a concern for elegant design and the depiction of idealized female figures. However, Schwabe's primary focus remained on the symbolic and spiritual content, aligning him more firmly with Symbolism. His work also shows an awareness of earlier masters; beyond the Renaissance influences, one can see a kinship with the visionary art of William Blake in its spiritual intensity and imaginative power. The influence of Japanese prints, with their flattened perspectives and decorative compositions, can also be discerned in some of his works, a common feature among many artists of this period, including Vincent van Gogh and Gustav Klimt. Klimt, a leading figure of the Vienna Secession, also explored Symbolist themes with a highly decorative and often erotic sensibility, providing another point of comparison in the broader European Symbolist landscape.

Later Years, Recognition, and Enduring Legacy

Carlos Schwabe continued to work and exhibit throughout the early 20th century. His artistic contributions were recognized with significant honors. In addition to the gold medal at the 1900 Exposition Universelle for The Death of the Gravedigger, he was awarded the prestigious French Légion d'honneur (Legion of Honour) in 1902, a testament to his standing in the French art world.

As artistic tastes began to shift with the rise of modernist movements like Fauvism, Cubism, and Expressionism, Symbolism gradually fell out of favor. However, Schwabe remained committed to his artistic vision. He continued to produce paintings and illustrations, though perhaps with less public prominence than in his heyday during the 1890s. He passed away in Avon, Seine-et-Marne, near Paris, on January 22, 1926.

In the decades following his death, Carlos Schwabe, like many Symbolist artists, was somewhat overshadowed by the dominant narratives of modern art. However, a renewed scholarly and public interest in Symbolism from the mid-20th century onwards has led to a greater appreciation of his unique contributions. His work is now recognized for its technical brilliance, its profound spiritual depth, and its quintessential expression of fin-de-siècle sensibilities.

Schwabe's legacy endures primarily through his powerful imagery, which continues to resonate with viewers drawn to art that explores the mystical and the transcendent. His illustrations, in particular, are considered among the finest examples of Symbolist book art, demonstrating a remarkable ability to create a harmonious dialogue between text and image. His influence can be seen in later fantasy art and illustration, where themes of myth, dream, and the supernatural are explored. Artists like Franz von Stuck, another contemporary who explored mythological and symbolic themes with a distinctive, often darker, intensity, also contributed to this vein of imaginative art that Schwabe so masterfully represented.

Conclusion

Carlos Schwabe was a distinctive and significant voice within the Symbolist movement. From his early training in Geneva to his mature career in Paris, he cultivated an art of profound introspection and spiritual aspiration. His meticulous technique, combined with a visionary imagination, allowed him to create works that are both aesthetically refined and thematically rich. Whether in his celebrated illustrations for Zola and Baudelaire or in his evocative paintings of death, angels, and mythological figures, Schwabe consistently sought to give form to the invisible realms of dream, emotion, and the spirit.

His engagement with the Salon de la Rose+Croix, his connections with literary figures, and his dialogue with contemporary artists place him firmly within the intellectual and artistic currents of his time. While the grand narratives of modernism once relegated Symbolism to a transitional phase, artists like Carlos Schwabe are now increasingly recognized for their intrinsic artistic merit and their crucial role in shaping a more complex understanding of art at the turn of the 20th century. His art remains a compelling testament to the enduring human quest for meaning and beauty beyond the confines of the material world, a quest that defined the very soul of Symbolism.