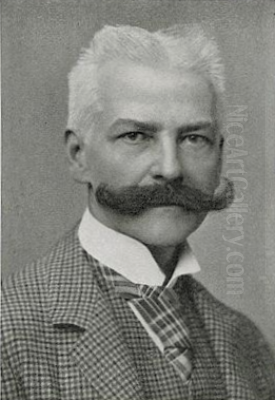

Albert von Keller stands as a significant, albeit sometimes overlooked, figure in German art at the turn of the 20th century. Born in Gais, Switzerland, on April 27, 1844, and passing away in Munich in 1920, Keller navigated the dynamic artistic landscape of his time with a unique blend of traditional skill and modern sensibility. Primarily known for his sophisticated portraits of women and evocative interior scenes, his work delved into the elegance of high society, the complexities of the human psyche, and the burgeoning interest in the paranormal. A founding member of the influential Munich Secession, Keller carved out a distinct path, influenced by but never fully beholden to the prevailing artistic currents.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Albert von Keller's origins were somewhat unconventional. He was born in Switzerland into a family that soon relocated to Bayreuth in Bavaria. His mother, Karoline Keller, was divorced at the time of his birth and had reverted to her maiden name, which Albert inherited. Speculation existed that his biological father might have been the brother of his mother's former husband. This complex family background perhaps subtly informed the psychological depth found in some of his later works. The family settled in Bayreuth when Albert was about three years old, and it was here he received his early education, which included learning the piano, hinting at an early sensitivity to the arts.

Initially, Keller pursued a more conventional path, enrolling at the University of Leipzig in 1863 to study law. However, the pull towards art proved stronger. By 1865, he had made the decisive shift, dedicating himself entirely to painting. He moved to Munich, a burgeoning center for the arts in Germany, and briefly attended the prestigious Academy of Fine Arts. Despite this short formal stint, Keller was largely an autodidact, honing his skills through independent study, private instruction, and careful observation of other artists.

His formative years in Munich exposed him to the work and influence of prominent figures. He absorbed lessons from the opulent and theatrical style of Hans Makart and the refined portraiture techniques of Franz von Lenbach, two leading artists of the Munich school. He also reportedly studied or worked alongside Ludwig von Hagn and Arthur von Ramberg, further developing his technical foundation. This period was crucial in shaping his painterly approach, blending academic rigor with a growing personal style.

Ascendancy in the Munich Art World

Keller quickly established himself within the Munich art scene. His talent for capturing likeness and atmosphere, particularly in depictions of elegant women in refined settings, found favour. A significant turning point in his personal and professional life came in 1878 when he married Irene von Eichthal, the daughter of a prominent banker. This union provided him with considerable financial security, freeing him from the immediate commercial pressures faced by many artists and allowing him greater artistic freedom.

His home, supported by his wife's wealth, became a notable gathering place for Munich's upper crust and artistic circles. This immersion in high society provided him with both subjects and an environment that deeply influenced his work during this period. His paintings often featured sophisticated women in luxurious interiors, adorned in fashionable attire. These works resonated with the tastes of the time and showed a clear affinity with the French Salon painting tradition, known for its polished technique and often narrative or genre scenes.

During travels, including stays in Italy, France, England, and the Low Countries, Keller further broadened his artistic horizons. His time in Paris was particularly significant, exposing him directly to the latest trends in French art. He developed a friendship with the successful Hungarian Salon painter Mihály Munkácsy, whose dramatic realism and rich textures likely resonated with Keller's own developing aesthetic. Keller's works began appearing in prestigious exhibitions, including the Paris Salon, gaining him international recognition.

The Munich Secession and Artistic Independence

The late 19th century saw a growing dissatisfaction among progressive artists with the conservative attitudes and exhibition practices of the established art academies. This led to the formation of Secession movements across Europe, aiming to promote artistic innovation and individuality. In 1892, Albert von Keller was among the founding members of the Munich Secession, a pivotal moment in German modern art.

The Munich Secession brought together artists seeking new forms of expression, breaking away from the historical and anecdotal subjects favored by the academy. Key figures associated with the movement included Franz von Stuck, Lovis Corinth, Max Liebermann, Max Slevogt, and Wilhelm Trübner. While diverse in their individual styles, they shared a commitment to artistic freedom, contemporary subject matter, and often a greater emphasis on painterly qualities like color and brushwork.

Keller played a significant role in the organization, serving as its Vice-President from 1904 until his death in 1920. His involvement underscored his position as a respected figure who bridged the gap between established society portraiture and more modern artistic concerns. While his work retained an elegance often associated with older traditions, its psychological undertones and evolving technique aligned with the Secession's spirit of inquiry and individualism. He successfully navigated being both a society painter and a proponent of modern art.

Exploring the Psyche and the Paranormal

Beyond the depictions of elegant society, a fascinating and distinctive aspect of Keller's oeuvre is his engagement with psychological and paranormal themes. This interest was not merely theoretical; he was an active participant in the intellectual currents exploring the hidden depths of the human mind and phenomena beyond conventional understanding. He became a member of the "Munich Psychological Society" (Psychologische Gesellschaft), a group dedicated to the study of parapsychological phenomena, including spiritualism, telepathy, and hypnosis.

This interest manifested directly in his life and art. Keller's salon was known not only for social gatherings but also for hosting séances and experiments related to these phenomena. In May 1887, he participated in a notable hypnosis experiment conducted by the physician and psychical researcher Baron Albert von Schrenck-Notzing, considered one of the first systematic investigations of "supernormal" phenomena under experimental conditions in Germany. Keller's fascination with these liminal states between consciousness and unconsciousness, reality and illusion, began to permeate his artwork.

His exploration of these themes connected him intellectually with other artists and thinkers intrigued by mysticism and the unseen, such as the Austrian painter Gabriel von Max, who was also deeply involved in spiritualism and Darwinian studies. Keller even created unique pieces like "spiritualist jewelry" in 1887. This engagement added a layer of complexity to his work, moving beyond surface appearances to probe the inner lives and hidden experiences of his subjects, particularly women, who were often the focus of spiritualist inquiry and psychological study at the time.

Artistic Style: Elegance, Expression, and Evolution

Albert von Keller's artistic style is characterized by its refinement, technical skill, and gradual evolution. His early works, heavily influenced by his studies and the prevailing tastes of the Munich school and French Salon, emphasize elegance and detailed rendering. He excelled at capturing the textures of luxurious fabrics – silks, velvets, furs – and the ambiance of opulent interiors. His brushwork in this period, while skilled, often aimed for a smooth, polished finish, emphasizing draftsmanship and careful composition. Works like Dame mit Pelzstola (Lady with Fur Stole, 1907), though from a slightly later period, retain this sense of sophisticated portrayal, focusing on the sitter's poise and the richness of her attire within an ornate setting.

Around the turn of the century, coinciding with his deep involvement in psychological exploration and the Secession movement, Keller's style began to shift. While he continued to paint society portraits, his approach became more expressive and psychologically charged. His brushwork loosened, becoming more visible and fluid, contributing to the overall mood of the piece. His palette sometimes explored more dramatic contrasts, and his compositions could take on a more symbolic weight.

This later phase saw the emergence of works dealing with more complex and sometimes darker themes. He produced decorative paintings featuring female nudes, but often imbued them with a sense of introspection or mystery rather than purely academic or erotic objectification. He tackled subjects like witchcraft, visions, and religious scenes, including depictions of the Crucifixion and a Höllenfahrt (Descent into Hell). These works often explored states of ecstasy, trance, or suffering. Traumtänzerin Madeleine (Dream Dancer Madeleine, 1904) is a prime example, depicting a female figure in a contorted pose suggesting a spiritual or hypnotic trance, a stark contrast to conventional representations of female beauty and sensuality. The psychological intensity in some of these later works might distantly echo the explorations of contemporaries like Edvard Munch, while the decorative qualities could be seen in parallel with Secessionist trends exemplified by artists like Gustav Klimt, though Keller always maintained his distinct artistic voice.

Throughout his career, Keller demonstrated a remarkable ability to blend different influences – the polish of the Salon, the introspection of Symbolism, the decorative flair of Jugendstil, and the painterly freedom of the Secession – into a coherent and personal style. He possessed a strong sense of color and an ability to create atmosphere, whether depicting the shimmering surfaces of a society drawing-room or the shadowy depths of a psychological state. His independence was key; sources note his conscious effort to avoid merely repeating fashionable trends or the work of others, striving always for a unique artistic statement.

Later Life, Recognition, and Legacy

Albert von Keller enjoyed considerable success and recognition during his lifetime. His standing in society was affirmed in 1898 when he was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Order of the Merit of the Bavarian Crown, which conferred personal nobility, allowing him to use the predicate "von" in his name. This honor reflected both his artistic achievements and his integration into the Bavarian establishment.

He remained an active figure in the Munich art world, continuing his leadership role in the Secession and exhibiting regularly. His studio remained a hub of social and artistic activity. His interactions extended beyond the visual arts; evidence suggests contact with the renowned writer Thomas Mann, indicating his presence within broader cultural circles in Munich.

Keller continued to paint prolifically until his death in Munich on July 14, 1920, at the age of 76. He left behind a substantial body of work that captures a specific moment in European cultural history – a time of transition between the certainties of the 19th century and the upheavals of the 20th. His art reflects the era's fascination with elegance and social ritual, but also its growing interest in the complexities of the human mind, the subconscious, and the spiritual realm.

His legacy is that of a highly skilled and versatile painter who successfully bridged different artistic worlds. He was a master portraitist, capturing the likenesses and social nuances of his time, particularly the world of sophisticated women. Simultaneously, he was an explorer of psychological depth and an active participant in the modernist impulses of the Munich Secession. While perhaps not as radical as some of his contemporaries, Albert von Keller's unique synthesis of tradition and modernity, elegance and introspection, secures his place as an important and intriguing figure in German art history. His work continues to attract interest for its technical brilliance, its atmospheric charm, and its fascinating glimpses into the hidden currents beneath the surface of Wilhelmine society.

Conclusion

Albert von Keller's career spanned a period of profound change in art and society. From his Swiss roots and formative years in Bavaria to his central role in the Munich art scene, he crafted a unique artistic identity. As a sought-after portraitist, he chronicled the elegance of his era with sensitivity and skill. As a founding member and leader of the Munich Secession, he championed artistic independence and engaged with modern themes. His fascination with psychology and the paranormal added a distinctive, introspective dimension to his work, setting him apart from many contemporaries. Though influenced by French Salon painting and connected to major figures like Makart, Lenbach, Stuck, and Max, Keller maintained a personal vision. He remains a compelling artist whose work offers insights into the aesthetic tastes, social life, and intellectual curiosities of Germany at the turn of the 20th century, balancing sophisticated representation with explorations of the unseen depths of human experience.