Luca Signorelli, born Luca d'Egidio di Ventura in Cortona around 1441-1445 and passing in the same city on October 16, 1523, stands as one of the most formidable and innovative painters of the Italian Renaissance. His work, characterized by a profound understanding of human anatomy, dynamic compositions, and a powerful, often unsettling, expressiveness, bridged the gap between the Early and High Renaissance. Signorelli's art left an indelible mark on his contemporaries and successors, most notably Michelangelo, and his frescoes in Orvieto Cathedral remain a monumental achievement in Western art.

Known also as Luca da Cortona, his artistic journey began in his native Tuscan town, but his talent soon led him to work in major artistic centers across Italy, including Florence, Rome, Siena, and Urbino. He absorbed the intellectual and artistic currents of his time, yet forged a style uniquely his own, marked by a vigorous naturalism and a dramatic intensity that set him apart.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Born into a respected family in Cortona, a town with a rich artistic heritage, Luca Signorelli's early artistic education is most significantly linked to Piero della Francesca. This apprenticeship, likely undertaken in Arezzo or perhaps even in Urbino where Piero worked for Duke Federico da Montefeltro, would have instilled in the young Signorelli a deep appreciation for perspective, clear compositional structure, and a certain gravitas in figural representation. Piero's influence is discernible in Signorelli's early handling of space and the monumental quality of his figures.

The artistic environment of central Italy during the mid-15th century was vibrant. Besides Piero della Francesca, artists like Fra Angelico and Benozzo Gozzoli were active, leaving behind significant works that would have been known to a budding painter. The intellectual climate, particularly in centers like Urbino, was steeped in humanism, fostering a renewed interest in classical antiquity, which would later become a hallmark of Signorelli's mature style.

His connection to Florence, the crucible of the Renaissance, was also crucial. While the exact nature and duration of his stays are debated, it is evident that Signorelli was profoundly impacted by the innovations occurring there. He would have encountered the work of masters such as Andrea del Verrocchio and the Pollaiuolo brothers, Antonio and Piero. These artists were at the forefront of anatomical studies and the depiction of the human body in motion, interests that Signorelli would pursue with unparalleled zeal.

Development of a Distinctive Artistic Style

Signorelli's artistic voice matured into one of remarkable power and individuality. A cornerstone of his style was his mastery of human anatomy. He depicted the nude male figure with an accuracy and dynamism that was groundbreaking. His figures are not merely anatomically correct but are imbued with a sense of muscular energy, tension, and often, profound psychological states. This fascination with the human form in all its expressive potential became a defining characteristic of his oeuvre.

His compositions are often complex and densely populated, yet he maintained clarity through strong underlying structures and a sophisticated use of perspective. He could marshal large groups of figures into coherent and dramatic narratives, creating scenes of immense visual impact. This ability was particularly evident in his large-scale fresco cycles, where he orchestrated vast, unfolding dramas across expansive wall surfaces.

Signorelli's use of color was robust and often contributed to the emotional tenor of his scenes. While capable of subtle harmonies, he also employed strong, sometimes stark, color contrasts to heighten drama. His handling of light and shadow, or chiaroscuro, was adept, modeling his figures with a sculptural solidity that gave them a tangible presence. This three-dimensional quality was further enhanced by his strong, incisive draftsmanship.

Narrative intensity is another key feature of Signorelli's art. He was a powerful storyteller, capable of conveying complex theological or mythological themes with clarity and emotional force. His figures are not passive participants but active agents in the unfolding drama, their gestures and expressions conveying a wide range of human emotions, from divine ecstasy to infernal torment.

Early Commissions and the Sistine Chapel

Signorelli's reputation grew steadily, leading to significant commissions. Among his early documented works are frescoes in Città di Castello and participation in the decoration of the Sacristy of the Sanctuary of the Holy House of Loreto (circa 1477-1480), where he worked alongside other prominent artists, possibly including Melozzo da Forlì, whose interest in foreshortening and perspective would have resonated with Signorelli.

A pivotal moment in his career was his involvement in the decoration of the Sistine Chapel in the Vatican, around 1481-1482. He was called to Rome, likely at the recommendation of Pietro Perugino, to assist in the ambitious project initiated by Pope Sixtus IV. Here, he worked alongside a stellar team of artists that included Perugino himself, Sandro Botticelli, Domenico Ghirlandaio, and Cosimo Rosselli.

Signorelli is credited with painting at least one major scene on the chapel walls, the Testament and Death of Moses. This fresco demonstrates his burgeoning mastery of complex figural arrangements and dramatic narrative. The landscape is expansive, and the figures, particularly the nudes in the foreground, showcase his characteristic anatomical precision and vigor. His contribution to the Sistine Chapel, though perhaps overshadowed by Michelangelo's later ceiling and Last Judgment, solidified his status as one of Italy's leading painters.

The Orvieto Cathedral Masterpiece: The San Brizio Chapel

The crowning achievement of Luca Signorelli's career is undoubtedly the fresco cycle in the San Brizio Chapel (also known as the Cappella Nuova) in Orvieto Cathedral. Commissioned in 1499, he took over a project that had been started decades earlier by Fra Angelico and Benozzo Gozzoli, who had completed only parts of the vault. Signorelli was tasked with decorating the remaining vast wall surfaces with scenes depicting the End of the World, the Last Judgment, and the fates of the Damned and the Blessed. He worked on this monumental undertaking until 1504.

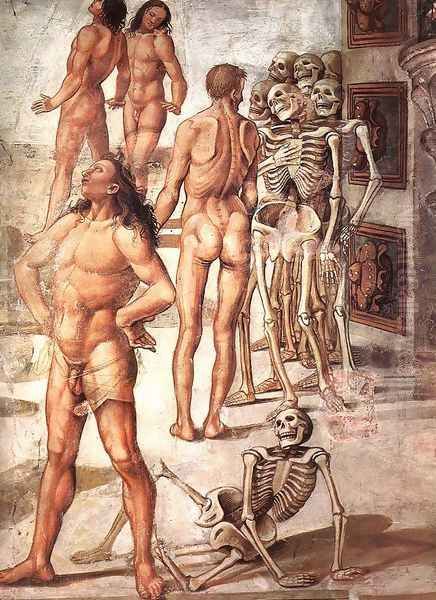

The Orvieto frescoes are a tour-de-force of artistic imagination and technical skill. They represent one of the most powerful and comprehensive depictions of apocalyptic themes in Renaissance art. Signorelli unleashed his full creative energy, populating the chapel with a multitude of figures, many of them nude, in dynamic and often contorted poses.

One of the most striking scenes is The Sermon and Deeds of the Antichrist. Here, Signorelli portrays the Antichrist, a figure closely resembling Christ, deluding the masses with false miracles and promises. The scene is filled with contemporary portraits, including possibly Signorelli himself and Fra Angelico, and a palpable sense of unease and impending doom. The depiction of demonic influence and human gullibility is rendered with chilling realism.

Equally powerful is The Resurrection of the Flesh, where skeletons and re-clothed bodies rise from the earth, their forms rendered with astonishing anatomical detail. This scene showcases Signorelli's profound knowledge of the human body, acquired, according to Giorgio Vasari, through dissections. The figures convey a range of reactions, from bewilderment to hope, as they await judgment.

The Damned Cast into Hell is a terrifying vision of divine retribution. Demons, depicted with grotesque inventiveness, torment the souls of the damned. The writhing, muscular bodies of the condemned are portrayed with an unflinching intensity, their faces contorted in agony. This scene, in particular, is often cited as a direct precursor to Michelangelo's Last Judgment in the Sistine Chapel.

In contrast, The Elect in Paradise offers a vision of serene bliss, though even here, Signorelli's figures retain a certain robust physicality. Angels make music, and the blessed, crowned with laurel wreaths, enjoy eternal peace. The overall impact of the San Brizio Chapel is overwhelming, a testament to Signorelli's ambition, his intellectual depth, and his unparalleled ability to translate complex theological concepts into compelling visual narratives. The influence of Dante Alighieri's Divine Comedy is palpable throughout these dramatic scenes.

Other Notable Works and Panel Paintings

While the Orvieto frescoes are his most famous works, Signorelli was also a prolific painter of altarpieces and panel paintings for churches, confraternities, and private patrons throughout Umbria, Tuscany, and the Marches. These works further demonstrate his stylistic range and thematic concerns.

His Madonna and Child compositions, such as the one in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence or the Pitti Palace, often feature strong, sculptural figures of the Virgin and Child, sometimes set against classical architectural backgrounds or landscapes populated by nude figures, reflecting his humanist interests. These works combine a tender religiosity with a powerful physical presence.

The Flagellation of Christ, now in the Brera Pinacoteca, Milan, is a stark and dramatic composition, notable for its classical architectural setting and the powerfully rendered figures. The emotional intensity of the scene is conveyed through the dynamic poses and the expressive faces of the participants. Another significant work is the Crucifixion with Mary Magdalene (Uffizi), which showcases his ability to convey profound pathos.

A particularly poignant work is the Lamentation over the Dead Christ, painted for the Church of Santa Margherita in Cortona (now in the Museo Diocesano, Cortona). According to Vasari, Signorelli painted this work shortly after the death of his beloved son Antonio from the plague in 1502. Vasari recounts that Signorelli, despite his immense grief, had his son's body brought to him and, with stoic resolve, painted his likeness to always have him before his eyes. The painting is a deeply moving expression of sorrow, with the figures of Christ and the mourners rendered with characteristic strength and emotional depth.

Other important commissions include the Adoration of the Magi (Louvre, Paris), the Circumcision (National Gallery, London), and numerous altarpieces for churches in Cortona, Città di Castello, Umbertide, and other towns. These works often feature his signature robust figures, complex compositions, and a keen attention to detail. He often collaborated with a workshop, which included his nephew Francesco Signorelli, to fulfill the many commissions he received.

Civic Life and Later Years

Beyond his artistic endeavors, Luca Signorelli was an active and respected citizen of Cortona. He held various public offices throughout his life, demonstrating a commitment to the civic affairs of his native city. He was elected to the "Council of 18," a significant governing body, in 1479 and served in other magisterial roles, indicating the high esteem in which he was held by his fellow citizens.

His artistic activity continued unabated into his later years. Even after suffering a stroke around 1520, which reportedly left him partially paralyzed, he continued to accept commissions and oversee his workshop. Vasari describes him as a man of great integrity and a courteous gentleman, beloved by his friends and patrons. He was known for his diligence and his passion for art, working, as Vasari put it, more for the pleasure of it than for monetary gain in his old age.

Luca Signorelli died in Cortona in 1523, at an advanced age for the period, likely around 80 years old. He was buried with honor in the Church of San Francesco in Cortona, a testament to his status as one of the city's most illustrious sons.

Influence and Legacy

Luca Signorelli's impact on the art of the Renaissance was profound and multifaceted. His bold exploration of human anatomy and movement, his dramatic compositions, and his powerful expressive style resonated deeply with his contemporaries and influenced the next generation of artists.

The most significant artist to draw inspiration from Signorelli was Michelangelo Buonarroti. Vasari explicitly states that Michelangelo "always expressed the highest admiration for the works of Luca, and particularly for his achievement at Orvieto," and that elements of Signorelli's Last Judgment were emulated by Michelangelo in his own version on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel. The dynamic nudes, the powerful musculature, and the sheer dramatic intensity of Signorelli's Orvieto frescoes undoubtedly provided a crucial precedent for Michelangelo's vision.

Raphael Sanzio, another giant of the High Renaissance, also held Signorelli in high esteem. While their styles differed, Raphael would have recognized the older master's command of composition and narrative. Donato Bramante, the great architect, was also a contemporary, and their paths may have crossed in artistic circles.

Signorelli's work can be seen as a vital link between the more ordered, perspectival concerns of Early Renaissance masters like his teacher Piero della Francesca and the dynamic, heroic style of the High Renaissance epitomized by Michelangelo and Raphael. He pushed the boundaries of figural representation, imbuing his subjects with a new level of physical and psychological presence. Artists like Andrea Mantegna shared a similar interest in classical forms and anatomical precision, though their stylistic solutions differed.

His influence extended to painters in Umbria and Tuscany, and his workshop helped to disseminate his style. While the High Renaissance soon gave way to Mannerism, with artists like Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino exploring even more exaggerated forms and emotional states, Signorelli's foundational work in anatomical expression and dramatic composition remained a touchstone.

Signorelli's Enduring Place in Art History

Luca Signorelli remains a pivotal figure in the history of Italian Renaissance art. His relentless pursuit of anatomical understanding, his ability to orchestrate complex and emotionally charged narratives, and the sheer power of his artistic vision set him apart. The frescoes of the San Brizio Chapel in Orvieto are not merely a highlight of his career but a landmark in the development of Western art, a profound meditation on life, death, and judgment that continues to captivate and awe viewers.

His art reflects the intellectual and spiritual currents of his time, a period of intense artistic innovation and profound religious feeling. He embraced the humanist revival of classical antiquity but infused it with a Christian sensibility and a deeply personal expressive power. From his early training with Piero della Francesca to his mature masterpieces, Signorelli forged a path that was both innovative and deeply rooted in tradition.

While perhaps not as universally recognized today as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, or Raphael, Luca Signorelli's contributions were essential to the flowering of the High Renaissance. His daring, his skill, and his profound understanding of the human condition, as expressed through the human form, secure his place as one of the great masters of his age, an artist whose work continues to speak with undiminished power across the centuries.