Alfred Jacob Miller stands as a pivotal figure in 19th-century American art, celebrated primarily for his evocative depictions of the American West. Born in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1810 and passing away in 1874, Miller captured a world on the cusp of profound change. He was among the very first artists to venture into the Rocky Mountains, documenting the landscapes, wildlife, Native American cultures, and the rugged lives of fur trappers and explorers. His work, steeped in the Romantic tradition, offers a unique and often idealized vision of the frontier, providing invaluable visual records from a time before photography became widespread in the region. This article delves into the life, art, influences, and enduring legacy of this pioneering artist.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Alfred Jacob Miller was born into a prosperous Baltimore family in 1810. His innate talent for drawing was recognized and encouraged early on, allowing him to pursue formal art training. His family's support was crucial in setting him on a path dedicated to the arts, a less common pursuit for young men of his standing at the time unless geared towards portraiture or historical subjects.

His foundational training occurred in Philadelphia between 1831 and 1832 under the tutelage of the renowned portraitist Thomas Sully. Sully, a leading painter known for his elegant and fluid style influenced by British portraiture, particularly Sir Thomas Lawrence, imparted valuable technical skills to Miller. During this period, Miller honed his abilities, producing portraits of notable Baltimore figures, including the influential merchant and art collector Robert Gilmor Jr. and the future philanthropist John Hopkins, whose early support, along with Gilmor's, was instrumental.

Seeking to broaden his artistic horizons, Miller embarked on a European tour from 1833 to 1834, a customary step for ambitious American artists of the era. He immersed himself in the art capitals of Paris, Rome, Bologna, and Venice. In Europe, he studied the Old Masters in museums like the Louvre, absorbing lessons from Renaissance and Baroque giants such as Andrea Mantegna, Leonardo da Vinci, Giorgione, and Nicolas Poussin, as well as Spanish masters. He also interacted with contemporary artists, including the celebrated Danish neoclassical sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen in Rome and the American sculptor Horatio Greenough. This European sojourn exposed him to diverse artistic styles and philosophies, particularly the burgeoning Romantic movement, which would profoundly shape his later work.

Upon returning to the United States in 1834, Miller attempted to establish himself professionally. He initially opened a studio in his native Baltimore, but faced with limited success, he relocated to New Orleans around 1836. New Orleans, a vibrant and culturally diverse city, offered more opportunities for a portrait painter. It was here, while seeking commissions, that a chance encounter would irrevocably alter the course of his life and artistic career.

The Journey West: A Defining Expedition

In New Orleans in early 1837, Alfred Jacob Miller met Captain William Drummond Stewart, a Scottish nobleman, veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, and adventurer on his second extended trip to the American West. Stewart was planning an ambitious expedition to the Rocky Mountains, specifically to attend the annual fur trappers' rendezvous, a large gathering of mountain men, Native Americans, and traders. Recognizing the unique opportunity to document this exotic and rapidly changing world, Stewart sought an artist to accompany him and record the journey's sights and experiences.

Impressed by Miller's talent, Stewart invited the young artist to join his party. For Miller, whose career had yet to fully flourish, this was an extraordinary opportunity. He readily accepted the commission, embarking in the spring of 1837 on a journey that would define his artistic legacy. The expedition traveled overland along the Oregon Trail, venturing deep into territory that few Euro-Americans, and even fewer artists, had ever seen.

The culmination of the journey was the Green River Rendezvous of 1837, held in the Wind River Mountains of present-day Wyoming. This raucous event was the last of the great mountain rendezvous before the decline of the beaver fur trade. Miller became the only artist ever to witness and sketch one of these legendary gatherings firsthand. His presence provided a unique visual record of the interactions between diverse groups – American trappers, French-Canadian voyageurs, representatives of the Hudson's Bay Company, and various Native American tribes including the Shoshone, Nez Perce, Crow, and Sioux.

This six-month expedition proved immensely formative for Miller. He filled sketchbooks with hundreds of drawings and watercolors, capturing the vast landscapes, dramatic geological formations, Native American encampments, buffalo hunts, and the daily lives of the mountain men. These field sketches, executed rapidly and often under challenging conditions, possessed an immediacy and authenticity that formed the bedrock of his Western oeuvre for the rest of his career.

Documenting the Frontier: Subjects and Themes

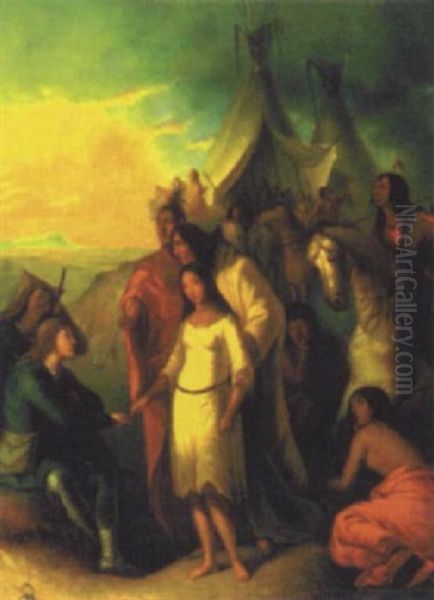

Miller's Western subjects were diverse, reflecting the rich tapestry of life he encountered on the 1837 expedition. His primary focus was on the people of the West. He sketched numerous portraits and scenes featuring Native Americans, often depicting them with a Romantic sensibility that emphasized their dignity, connection to nature, and distinct cultural practices. Tribes such as the Shoshone, Nez Perce, and Sioux feature prominently in his work, shown in camp life, hunting, traveling, or engaging in ceremonies.

He was equally fascinated by the mountain men, the rugged individuals who formed the vanguard of the fur trade. Figures like Antoine Clement, a hunter of mixed heritage who guided Stewart's party, became subjects for his art (e.g., Portrait of Antoine). Miller captured their distinctive dress, their expertise in survival, their interactions with Native Americans, and their solitary or communal lives in the wilderness. The Green River Rendezvous provided a wealth of material, showcasing the boisterous energy and cultural exchange of this unique frontier institution.

The landscape itself was a major protagonist in Miller's work. He was one of the first artists to depict the grandeur of the Rocky Mountains, capturing iconic landmarks like Independence Rock and the Wind River Range. His landscapes often convey a sense of awe and sublime beauty, emphasizing the vastness and untamed nature of the West. Sweeping vistas, dramatic skies, and unique geological features were rendered with an eye for both topographical detail and atmospheric effect.

Wildlife, particularly the American bison, also figured significantly. Buffalo hunts were a recurring theme, depicted with energy and drama, reflecting both the importance of the bison to Plains cultures and the excitement of the chase. Horses, essential for travel and hunting, are ubiquitous in his scenes, rendered with anatomical accuracy and a sense of vitality. Miller's work collectively provides a panoramic view of the Far West during a specific, transformative period.

Artistic Style and Influences

Alfred Jacob Miller's artistic style is best characterized as Romantic. Influenced by his European training and the prevailing artistic sentiments of the era, his work often prioritizes emotion, drama, and idealized beauty over strict realism. While his field sketches possess a directness born of observation, his finished studio pieces, particularly the oils and larger watercolors, often embellish reality for heightened effect.

His training under Thomas Sully is evident in the fluidity of his brushwork and his skill in portraiture. From his European studies, he absorbed the lessons of the Old Masters in composition and the handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), which he used effectively to create mood and focus attention. His admiration for classical forms, perhaps reinforced by encounters with Neoclassical artists like Thorvaldsen, sometimes informed his rendering of the human figure, lending a certain grace or nobility, particularly to his depictions of Native Americans. This sometimes led to portrayals aligning with the contemporary "noble savage" trope, an idealized view of indigenous peoples as embodying innate virtue and living in harmony with nature, untouched by the corruptions of civilization.

Compared to contemporaries who also depicted the West, Miller's approach differed. George Catlin, for instance, pursued a more ethnographic and documentary goal, albeit with his own stylistic conventions. Karl Bodmer, accompanying Prince Maximilian of Wied-Neuwied, produced highly detailed and accurate renderings of Native American life and landscapes. Miller's work, while providing valuable historical information, is generally softer, more atmospheric, and more overtly picturesque or dramatic. His use of watercolor was particularly adept, allowing for luminous effects and subtle gradations of tone well-suited to capturing the light and atmosphere of the plains and mountains.

His compositions often feature dynamic arrangements, diagonal lines, and a sense of movement, especially in hunting scenes or depictions of large groups. The landscapes serve not just as backdrops but as active participants, their scale and grandeur often dwarfing the human figures and emphasizing themes of adventure, solitude, and the power of nature.

Major Works and Mediums

Alfred Jacob Miller worked proficiently in several mediums, including oil paint, watercolor, and pencil or ink sketches. While he produced significant oil paintings, he is perhaps best known today for his extensive body of watercolors. Many of these were based directly on the sketches he made during the 1837 expedition.

Upon returning from the West, Miller first worked up many of his sketches into finished watercolors for his patron, William Drummond Stewart. A significant set of these was created during Miller's stay at Stewart's Murthly Castle in Scotland between 1840 and 1842. These watercolors, often accompanied by Miller's own descriptive notes, formed a narrative portfolio of the Western adventure. They were intended for Stewart's private collection and provide intimate, detailed views of the journey.

Miller continued to revisit his Western sketches throughout his career, producing multiple versions of popular scenes in both watercolor and oil for various patrons back in Baltimore and elsewhere. This practice means that several compositions exist in different iterations, sometimes varying in detail or emphasis.

Among his most recognized works are:

The Trapper's Bride: A famous and somewhat controversial painting depicting a mountain man taking a Native American wife, reflecting complex cultural interactions and contemporary attitudes.

Interior of Fort Laramie: A detailed view inside the important trading post, showing the mix of people (traders, Native Americans, voyageurs) and activities within its walls.

Buffalo Hunt or Chasing the Buffalo: Several dynamic compositions capturing the energy and danger of hunting bison on horseback.

Snake Indian Encampment: Scenes depicting the daily life of the Shoshone (often referred to as Snake Indians at the time).

The Lost Trapper: A narrative scene evoking the perils and solitude of life in the wilderness.

Rendezvous near Green River: Depictions of the bustling 1837 gathering, showcasing the trade and social interactions.

Portrait of Antoine: A sensitive portrayal of Antoine Clement, Stewart's Métis hunter.

The War Party: A watercolor showing a group of Native American warriors, held by the Walters Art Museum.

White Plume and Nez Percés Indian: Specific portraits of Native American individuals, also in the Walters collection.

Scene in the Rocky Mountains of America: Likely a title applied to various landscape views emphasizing the grandeur of the region.

These works, whether intimate watercolors or more formal oils, cemented Miller's reputation as the visual interpreter of the Rocky Mountain fur trade era.

Patronage and Professional Life

Patronage was crucial to Alfred Jacob Miller's career, particularly the support he received at key moments. The early encouragement and likely financial assistance from prominent Baltimoreans Robert Gilmor Jr. and John Hopkins enabled his initial studies and perhaps his European tour. Their belief in his talent provided a vital foundation.

Undoubtedly, his most significant patron was Captain William Drummond Stewart. Stewart not only provided the opportunity for the transformative 1837 expedition but also commissioned a large body of work based on it. The invitation to Murthly Castle in Scotland (1840-1842) allowed Miller dedicated time to produce finished oil paintings and watercolors documenting their shared adventure. These works adorned Stewart's Scottish estate, serving as elaborate souvenirs and testaments to his experiences in the American wilderness. Stewart's patronage effectively launched Miller's specialization in Western subjects.

After his return from Scotland around 1842, Miller settled permanently in Baltimore, establishing a studio where he worked for the remainder of his life. He continued to receive commissions for portraits from local families, maintaining the skills honed under Sully. However, his primary focus remained the American West. He capitalized on the public's growing fascination with the frontier, producing numerous replicas and variations of his most popular Western scenes for a clientele eager for images of this exotic realm.

While not achieving the widespread fame of some later Western artists during his lifetime, Miller maintained a steady career. He occasionally exhibited his work, and his studio became a known source for Western imagery. He also took on students, such as the Baltimore artist Andrew John Henry Way. Later in the 20th century, his works attracted interest from major collectors of American art, including figures associated with the Rockefeller family, contributing to the preservation and study of his oeuvre.

Contemporaries and Connections

Alfred Jacob Miller operated within a network of artists, patrons, and influences. His teacher, Thomas Sully, provided his foundational training in the Anglo-American portrait tradition. His European encounters connected him with international figures like the Danish sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen and fellow American expatriate artist Horatio Greenough. His primary patron, Sir William Drummond Stewart, was not an artist but the catalyst for his most important work.

In the realm of Western art, Miller was a pioneer. He journeyed West slightly after George Catlin began his extensive travels documenting Native American tribes, but before many others. Karl Bodmer, the Swiss artist, was in the West (specifically the Missouri River region) just a few years before Miller, producing remarkably detailed works. Miller's romantic style contrasts with Bodmer's precision and Catlin's more ethnographic, though still stylized, approach.

Other artists depicting the West or Native American subjects around the same mid-century period include John Mix Stanley, Seth Eastman (known for his work documenting the Mississippi River and military posts), and Charles Deas, who also painted dramatic scenes of mountain men and Native Americans, sometimes with a similarly Romantic flair.

Miller's legacy influenced later generations of Western artists. While direct mentorship might be limited, his popularization of Western themes paved the way for artists like Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington, who became icons of Western American art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, though their styles and focus (particularly on the cowboy era) differed significantly.

In the 20th century, Miller's work found resonance even with Pop artists. Roy Lichtenstein, known for his comic-book style, created works in the 1950s that directly referenced and reinterpreted paintings of the American West by artists like Miller and Remington, engaging with the mythology and imagery of the frontier. Miller's study of Old Masters like Andrea Mantegna, Leonardo da Vinci, Giorgione, and Nicolas Poussin during his European travels also connects him to a longer art historical lineage. His student, Andrew John Henry Way, carried on his own artistic career, primarily as a still-life painter, representing a direct, though stylistically divergent, connection.

Legacy and Influence

Alfred Jacob Miller's primary legacy lies in his role as one of the earliest and most artistically accomplished visual chroniclers of the American Far West, specifically the Rocky Mountain fur trade era. His 1837 journey provided him with unique source material that he mined for the rest of his career, creating a substantial body of work that introduced Eastern audiences and Europeans to the landscapes, peoples, and ways of life of a region largely unknown to them.

His work is invaluable as a historical record. As the only artist to document a Green River Rendezvous, his sketches and paintings offer irreplaceable insights into this significant aspect of Western history. His depictions of Native American life, while filtered through a Romantic lens, capture details of dress, customs, and material culture from a period of rapid change and before widespread displacement. Similarly, his images of mountain men provide a glimpse into their unique subculture.

Artistically, Miller brought a sophisticated European-influenced Romantic style to Western subjects. His emphasis on atmosphere, drama, and idealized beauty shaped popular perceptions of the West as a place of adventure, danger, and sublime natural grandeur. While later artists would depict the West with greater realism or focus on different aspects (like the cowboy or Plains warfare), Miller established the West as a viable and compelling subject for American art.

His influence can be seen in the continuation of Western themes in American art, paving the way for later artists like Charles M. Russell and Frederic Remington. Although his work was not widely known to the general public during much of his lifetime, concentrated in private collections like Stewart's, it gained increasing recognition in the 20th century. Scholars and collectors rediscovered his contributions, appreciating both the artistic merit and historical significance of his paintings and watercolors. His work has been subject to critical re-evaluation, examining his Romanticized portrayals, particularly of Native Americans, within the context of 19th-century attitudes. Modern artists like Roy Lichtenstein have engaged with his imagery, demonstrating its enduring presence in American visual culture.

Collections and Where to See His Work

Alfred Jacob Miller's works are held in numerous public and private collections, primarily in the United States. Several institutions hold significant collections, making his art accessible to the public.

The Walters Art Museum in his hometown of Baltimore holds arguably the most important collection of Miller's watercolors, including many of the finished pieces created for William Drummond Stewart, originally from the Murthly Castle portfolio. Works like The Trapper's Bride, Interior of Fort Laramie, and numerous scenes of Native American life and the rendezvous can be found here.

The Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma, which specializes in American West art, also holds a substantial collection of Miller's oils and watercolors.

The American Heritage Center at the University of Wyoming in Laramie houses Miller works, particularly significant given Wyoming's connection to the location of the 1837 rendezvous. They have hosted exhibitions featuring his art, drawing from collections like the Everett D. Graff Collection.

The Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha, Nebraska, holds important works related to early Western exploration, including watercolors by Miller, alongside works by Karl Bodmer.

Other institutions with notable Miller holdings or that have featured his work in exhibitions include:

The Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art in Indianapolis.

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City.

The Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming.

The Amon Carter Museum of American Art in Fort Worth, Texas.

These collections allow viewers to experience firsthand the artistry and historical importance of Miller's depictions of the American West. Temporary exhibitions focusing on Miller or themes of Western exploration frequently draw upon these and other collections.

Conclusion

Alfred Jacob Miller occupies a unique and vital place in American art history. As an artist-explorer, he ventured into the Rocky Mountains at a pivotal moment, capturing the final years of the fur trade rendezvous system and the lives of those who inhabited the region. His Romantic style, honed through training in Philadelphia and Europe, lent drama and beauty to his depictions, shaping perceptions of the American West for generations. While his work reflects the perspectives and idealizations of his time, it remains an invaluable visual resource for understanding the history and culture of the 19th-century American frontier. Through his prolific output of sketches, watercolors, and oils, Miller ensured that the fleeting world he witnessed would not be entirely lost to time, leaving behind a rich legacy that continues to fascinate and inform.