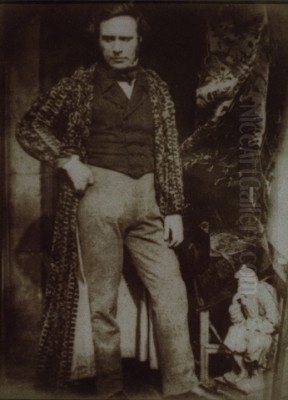

George Harvey, an artist whose life and career bridged the Atlantic, remains a fascinating figure in nineteenth-century art history. Born in England in 1800, he spent a significant portion of his productive years in the United States before returning to his homeland, leaving behind a legacy rich in atmospheric landscapes and delicate miniatures. His work captures a unique sensitivity to the nuances of light and environment, reflecting both British artistic traditions and the burgeoning landscape movement in America.

Early Life and American Beginnings

George Harvey was born in Tottenham, England. Like many ambitious young individuals of his time, he looked across the Atlantic for opportunity. In 1820, at the age of twenty, he emigrated to the United States, seeking his fortune. His initial path into the art world was through the intricate and demanding medium of miniature painting, a popular form of portraiture before the widespread adoption of photography.

His early years in America were marked by adventure. Harvey reportedly spent time in the relative wilderness of Ohio, engaging in activities far removed from a London upbringing. He is said to have spent time hunting, trapping, sketching, and painting in these frontier environments. This direct engagement with the American landscape likely sowed the seeds for his later focus on capturing its essence, even as he initially pursued the more commercially viable path of a miniaturist. His skills in this area provided a foundation for his artistic career in his adopted country.

A Shift Towards Landscape

Harvey established himself as a capable miniaturist, gaining commissions and recognition. However, his career trajectory took a significant turn due to health concerns. Facing physical challenges that made the intense, close work required for miniatures difficult, Harvey was compelled to shift his artistic focus. He turned his attention increasingly towards landscape painting, a genre that allowed for broader expression and perhaps a less physically taxing process.

This shift coincided with a growing appreciation for landscape painting in America, particularly the rise of what would become known as the Hudson River School. While not always formally categorized as a member of this school, Harvey shared many of its core interests. He developed a profound fascination with atmospheric effects – the changing light, the haze, the weather – and how these elements shaped the appearance and mood of the natural world. This focus became a defining characteristic of his landscape work.

Artistic Style and Vision

George Harvey's mature style is most noted for its delicate handling of watercolor and its keen sensitivity to atmospheric conditions. He possessed a remarkable ability to capture the subtle gradations of light and color in the sky and their effect on the land below. His works often convey a sense of tranquility and poetic beauty, reflecting the influence of British Romantic landscape traditions, particularly the emphasis on light found in the works of masters like J.M.W. Turner and John Constable.

His time in America deeply influenced his subject matter. He sought to depict the specific qualities of the American climate and landscape, noting the differences in light and atmosphere compared to England. This led to series like his Atmospheric Landscapes of the Northeast, where he meticulously documented the visual character of different times of day and seasons. His technique often involved careful layering of watercolor washes to achieve luminosity and depth.

While primarily known for landscapes, Harvey's oeuvre also included genre scenes. Works like The Cowgirl suggest an interest in depicting rural life and the human figure within the landscape, sometimes touching upon themes of solitude or the quiet dignity of everyday existence. This hints at an awareness of social realism, adding another dimension to his artistic output beyond pure landscape.

Exploring Nature's Nuances

Harvey's dedication to capturing atmospheric nuance is evident across his body of work. He wasn't merely painting topography; he was painting the air, the light, and the feeling of a place at a specific moment. His watercolors, in particular, allowed him to achieve a transparency and immediacy well-suited to rendering fleeting effects like mist, dawn light, or the glow of sunset.

He understood that the landscape was not static but constantly transformed by the conditions surrounding it. This fascination led him to create series that explicitly explored these changes, such as paintings depicting the same scene during Morning, Noon, Evening, and Night. This systematic approach reveals an almost scientific curiosity alongside his artistic sensibility, aiming to understand and represent the cyclical rhythms of nature.

Representative Works

Several works stand out as representative of George Harvey's artistic achievements. His series, Atmospheric Landscapes of the Northeast, executed primarily in watercolor, is perhaps his most defining contribution, showcasing his mastery of light and atmosphere in depicting the American landscape. These works were intended not just as individual paintings but as part of a larger project documenting the unique environmental qualities of the region.

Specific paintings like Pittsford on the Erie Canal capture the picturesque beauty of American scenery during a period of national expansion and development. It reflects a quiet, pastoral vision of the nation. The Bow in the Cloud is another notable landscape, likely imbued with the symbolic and spiritual connotations often associated with rainbows in nineteenth-century art, suggesting themes of hope and divine presence in nature.

His series exploring different times of day – Morning, Noon, Evening, and Night – further exemplifies his focus on transient effects. Although he moved away from miniatures due to health, his early work in this genre should also be acknowledged as part of his artistic foundation. Furthermore, some sources attribute historical and religious subjects with Scottish themes to him, such as The Battle of Drumclog, Covenanter's Commission, and Highland Funeral. While these subjects were more commonly associated with the Scottish painter Sir George Harvey (a contemporary, but a different artist), their attribution to this George Harvey in some records points to the breadth of themes he may have engaged with or potential historical confusion. His work The Cowgirl also stands out, representing his engagement with genre scenes and rural life.

Exhibitions, Publications, and Promotion

Harvey actively sought to bring his work before the public. A significant event was his large exhibition held in 1844 at the prestigious Boston Athenæum. This show featured an impressive 213 works, including miniatures and landscapes, demonstrating the breadth of his output and his established presence in the American art scene, particularly in Boston and New York where he primarily worked.

He harbored ambitions beyond individual exhibitions. Harvey conceived a plan to publish a lavishly illustrated book documenting American scenery, capturing its unique atmospheric characteristics. Unfortunately, this ambitious project ultimately failed to materialize due to a lack of sufficient funding, a common challenge for artists undertaking large-scale publishing ventures at the time.

Despite this setback, he did succeed in publishing a set of aquatints titled Harvey's Scenes of the Primitive Forest of America, at the Four Periods of the Year (often related to his Atmospheric Landscapes project) around 1841. For this, he collaborated with the skilled engraver William J. Bennett, known for his topographical views. This publication helped disseminate Harvey's vision of the American landscape to a wider audience.

Bridging Continents with Art and Light

One of George Harvey's most innovative contributions lay in his use of technology for art promotion and education. He embraced the magic lantern, a precursor to the slide projector, to create presentations he called "Dissolving Views." Using painted glass slides based on his watercolors, he could project large, luminous images of American landscapes, often transitioning smoothly between scenes or different times of day.

He advertised these shows in American newspapers like the Boston Post and the New-York Daily Tribune. Crucially, he also took his show across the Atlantic. He delivered lectures accompanied by these dissolving views in Britain, offering audiences there a vivid, immersive experience of the American scenery and its peculiar atmospheric effects. This was a pioneering effort in using visual technology for transatlantic cultural exchange, introducing the beauty of the New World to the Old in a compelling format.

His entrepreneurial spirit extended to leasing his popular slide show. Notably, he rented it to a young Albert Bierstadt, who would later become one of the most famous painters of the American West. Bierstadt toured with Harvey's show in New Bedford and Providence, using Harvey's images and selling accompanying pamphlets, gaining valuable early experience in presenting landscape art to the public.

Artistic Circles and Connections

Throughout his career, George Harvey interacted with prominent figures in the artistic and literary worlds. His most significant connection was perhaps with the celebrated American author Washington Irving. The two were friends, and Harvey assisted Irving in the architectural design and interior decoration of Sunnyside, Irving's famous home in Tarrytown, New York. Harvey reportedly applied his watercolor techniques to the home's decoration. Irving, in turn, may have provided text or support for Harvey's artistic projects.

In the Boston art scene, Harvey would have been aware of, and likely known, major figures such as Washington Allston, a leading painter of the previous generation whose Romantic sensibilities resonated with Harvey's own interests. His collaboration with the engraver William J. Bennett on the 1841 publication placed him in the network of printmakers and publishers vital to disseminating art.

His leasing of the lantern slide show to Albert Bierstadt connects him to the next generation of American landscape painters, who would take the depiction of grand scenery even further. Furthermore, Harvey's recognition within the American art establishment was solidified by his election as an Associate Member of the prestigious National Academy of Design in New York in 1828. This placed him among the ranks of influential American artists like Samuel F.B. Morse (the Academy's founder), Thomas Sully, and Asher B. Durand.

Later Life and Return to England

After decades spent living and working primarily in the United States, George Harvey made the decision to return permanently to his native England in 1873. He settled in Wimbledon, near London, where he spent the remaining years of his life. He continued to paint, focusing mainly on landscapes, until his death in 1878.

His return marked the closing of a career uniquely positioned between two nations. He had absorbed influences from both British and American art traditions and contributed to the visual culture of both countries. His life reflects the dynamic exchange of ideas and people across the Atlantic during the nineteenth century.

Legacy and Contribution

George Harvey occupies a distinct place in nineteenth-century art history. While perhaps not as widely celebrated today as the leading figures of the Hudson River School like Thomas Cole or Frederic Edwin Church, or British giants like Turner, his contribution is significant. He excelled in capturing the specific atmospheric qualities of the American Northeast with a sensitivity honed by his British training and his personal observations.

His primary legacy lies in his delicate and evocative landscape watercolors, which masterfully render light and atmosphere. He was an important figure in popularizing American scenery, both within the United States and particularly in Britain, through his innovative use of "Dissolving Views" lantern slide shows. This pioneering use of visual technology for art presentation and education marks him as forward-thinking.

He was an artist deeply engaged with the nuances of the natural world, translating his observations into works that conveyed both beauty and a sense of place. His membership in the National Academy of Design attests to the respect he garnered among his American peers. Harvey's career demonstrates the interconnectedness of the British and American art worlds and highlights the importance of artists who moved between them, enriching both traditions.

Conclusion

George Harvey's life journey from Tottenham to the Ohio frontier, to the art centers of Boston and New York, and finally back to England, is reflected in his diverse artistic output. From detailed miniatures to expansive, light-filled landscapes, his work consistently shows a refined sensibility and technical skill. He was an astute observer of nature, a talented watercolorist, an innovator in art presentation, and a vital link in the transatlantic artistic exchange of the nineteenth century. His paintings continue to offer viewers a subtle and poetic vision of the landscapes he knew and loved on both sides of the Atlantic.