George Morland stands as a fascinating and somewhat tragic figure in the annals of British art history. Active during the latter half of the eighteenth century, he rose to immense popularity for his evocative depictions of English rural life, capturing the rustic charm of the countryside, its inhabitants, and its animals with a unique blend of realism and sentiment. Yet, his prodigious talent and commercial success were perpetually shadowed by a tumultuous personal life marked by extravagance, debt, and alcoholism, ultimately leading to a premature death. Despite the uneven quality of his vast output, Morland's work offers an invaluable window into the social fabric and visual culture of Georgian England, influencing subsequent generations of artists and leaving behind a legacy complex as the man himself.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

George Morland was born in London on June 26, 1763. Artistry ran deep in his family. His father, Henry Robert Morland (c. 1716-1797), was a painter of portraits and genre scenes, as well as an art dealer and restorer, though his career was often hampered by financial instability; he experienced bankruptcy more than once. George's grandfather, George Henry Morland, was also a painter. His mother, Jenny Lacam, was said to be of French descent. George was one of six children, and his innate artistic gifts became apparent from a remarkably young age.

Recognizing his son's potential, Henry Robert Morland subjected George to a rigorous, almost reclusive, apprenticeship from his early years. The young Morland was largely confined to his father's studio, tasked with copying works by Old Masters, particularly those of the Dutch and Flemish schools like Adriaen van Ostade and David Teniers the Younger, as well as reproducing pictures and drawings for sale. This intensive training honed his technical skills exceptionally quickly. Evidence of his precocity is clear: as early as ten years old, his drawings were accomplished enough to be exhibited at the prestigious Royal Academy of Arts in London.

This period of intense, isolated study under his father's strict control instilled in Morland a remarkable facility with drawing and painting but also perhaps sowed the seeds of his later rebellion against constraint. He developed an extraordinary ability to observe and render detail, a skill that would become a hallmark of his mature work. However, the lack of conventional social interaction and freedom during these formative years likely contributed to his later excesses when he finally gained independence.

Launching an Independent Career

Around the age of seventeen, Morland began to break free from his father's direct supervision, although he remained formally apprenticed until he was twenty-one (around 1784). He started producing original works and selling them, quickly finding a market for his burgeoning talent. His early subjects often included sentimental themes, moralistic narratives, and charming scenes of childhood, reflecting popular tastes of the time, possibly influenced by artists like Francis Wheatley.

A pivotal year for Morland was 1786. In July, he married Anne Ward, the sister of the highly skilled engraver William Ward (1766-1826). This union forged a crucial professional link. William Ward would become one of the principal engravers of Morland's paintings, translating his popular canvases into prints that reached a vast audience across Britain and even continental Europe. The connection deepened a month later when William Ward married Morland's sister, Maria. For a short, experimental period, the two couples shared a house, but temperamental differences reportedly led to the arrangement dissolving within three months.

Despite the brief domestic experiment, the professional relationship between Morland and William Ward proved immensely fruitful. The widespread dissemination of engravings after Morland's paintings, expertly executed by Ward and other prominent engravers like his brother James Ward (who was also a notable painter, particularly of animals) and John Raphael Smith, was key to establishing Morland's fame and generating significant income, at least initially.

The Peak of Popularity: Capturing Rural England

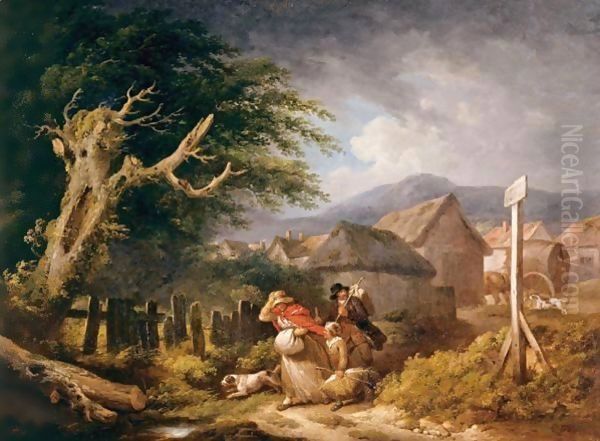

The late 1780s and early 1790s marked the zenith of George Morland's popularity and artistic output. He tapped into a growing appreciation for rustic simplicity and the picturesque, a counterpoint to the formality of aristocratic portraiture dominated by figures like Sir Joshua Reynolds and the classical landscapes favored by artists such as Richard Wilson. Morland offered scenes that felt authentic and relatable: cozy cottage interiors, bustling stable yards, farmers tending their livestock, gypsies encamped by the roadside, and convivial gatherings at country inns.

His subjects were drawn from the everyday life he observed, often during excursions outside London or time spent mingling in rural taverns and stables. He possessed an uncanny ability to capture the textures and atmosphere of these environments – the rough-hewn wood of stable doors, the gleam of straw under lantern light, the shaggy coats of donkeys, and the contented grunts of his famously rendered pigs. Unlike the highly idealized pastoral scenes of some earlier traditions, Morland's work, while often charming, retained a sense of lived reality.

His paintings resonated with a broad audience, from the landed gentry decorating their country houses to the burgeoning middle class seeking affordable prints for their homes. The demand for his work became immense. He was incredibly prolific, reportedly capable of finishing small canvases with astonishing speed, sometimes completing several in a single day, particularly later when driven by the need to pay off debts. This period saw the creation of many of his most characteristic and admired works.

Artistic Style: Naturalism and Dutch Influence

Morland's style is characterized by its naturalism, relatively loose brushwork (which became freer, sometimes even hasty, in later years), and an earthy palette often warmed by subtle effects of light. His compositions are typically straightforward and unpretentious, focusing on the central subject without unnecessary embellishment. He excelled at depicting animals, not with the scientific precision of a George Stubbs, but with a keen sense of their character and place within the rural ecosystem. His pigs, in particular, became almost a trademark, rendered with affectionate realism.

The influence of 17th-century Dutch and Flemish genre painting remained evident throughout his career. The rustic interiors recall the work of Adriaen van Ostade and Adriaen Brouwer, while his handling of light and atmosphere in landscapes and stable scenes sometimes echoes Aelbert Cuyp. However, Morland adapted these influences to a distinctly English context, creating scenes that felt contemporary and specific to his own time and place.

Compared to the topographical exactitude of watercolourists like Paul Sandby, Morland's landscapes were more concerned with atmosphere and human (or animal) incident. While Thomas Gainsborough also painted rustic scenes, Morland's approach was generally less idealized and more focused on the humbler aspects of country life. His direct, observational style provided a foundation for the greater realism that would emerge in British landscape painting in the following century with artists like John Constable.

Representative Works and Key Themes

Morland's vast output makes selecting just a few representative works challenging, but several stand out and encapsulate his primary themes:

_Inside of a Stable_ (1791, National Gallery, London): This is perhaps Morland's most famous painting and a quintessential example of his stable scenes. It depicts a spacious, dimly lit stable interior where figures attend to horses. The play of light filtering through the doorway, the detailed rendering of the straw-covered floor, the textures of wood and brick, and the relaxed poses of the animals and humans create a powerful sense of atmosphere and authenticity. It showcases his mastery of composition and his sympathetic portrayal of everyday rural labour.

Rural Inns and Cottages: Works like The Public House (c. 1790, Tate Britain) and The Village Inn Door (1792, Tate Britain) capture the social hubs of country life. He depicted travellers resting, locals conversing, and animals waiting patiently outside. Similarly, his cottage scenes often show families engaged in simple domestic activities, emphasizing warmth and intimacy, though sometimes hinting at poverty.

Animal Subjects: Beyond the stable scenes, Morland frequently painted animals as central subjects, particularly pigs, donkeys, and sheep, often in outdoor settings. These works highlight his skill in capturing animal anatomy and behaviour with empathy and without excessive sentimentality.

Coastal Scenes and Smugglers: Seeking refuge from creditors, Morland spent time on the Isle of Wight around 1790-1791. This period inspired numerous coastal scenes, often featuring fishermen, shipwrecks, and smugglers – subjects that added a touch of drama and adventure to his repertoire. The Storm (1790s, Louvre) is an example of his engagement with the power of nature, a theme also explored dramatically by contemporaries like Philip James de Loutherbourg.

Gypsy Encampments: Morland was one of several artists of the period, including Julius Caesar Ibbetson, drawn to depicting the lives of gypsies and travellers. These scenes allowed him to explore themes of freedom, marginality, and the picturesque aspects of life outside settled society.

Social Commentary: The Anti-Slavery Paintings

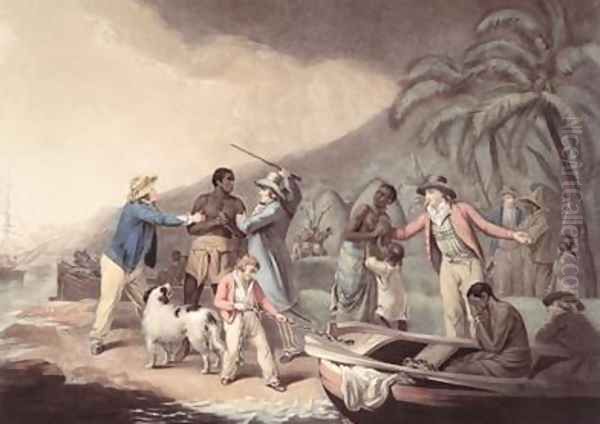

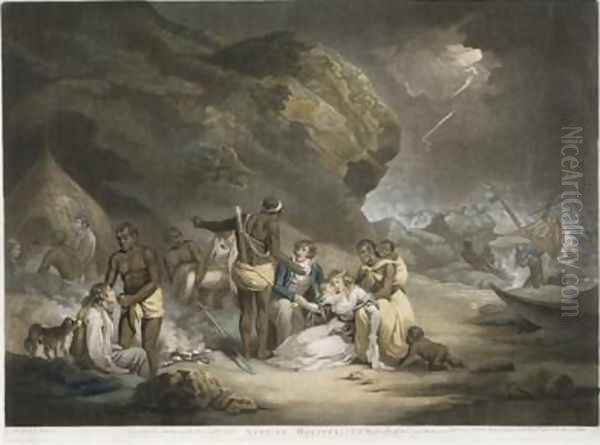

While primarily known for his rustic genre scenes, Morland also tackled more profound social issues, most notably the transatlantic slave trade. In 1788, he exhibited Execrable Human Traffick, or the Affectionate Slaves (later known simply as The Slave Trade) at the Royal Academy. A companion piece, African Hospitality, followed in 1789. The Slave Trade depicted the harrowing scene of an African family being torn apart on a beach by European slave traders. African Hospitality showed shipwrecked European sailors being rescued by Africans.

These paintings were created during a peak period of the abolitionist movement in Britain. Morland's decision to address this controversial topic in major exhibition works was significant. The paintings were widely disseminated through engravings by John Raphael Smith, becoming powerful pieces of abolitionist propaganda. They represent a rare instance of Morland engaging directly with contemporary political and moral debates, demonstrating a social conscience that adds another layer to his artistic identity. These works stand as important early examples of anti-slavery imagery in British art.

Collaboration, Reproduction, and Commercial Pressures

The partnership with engravers, especially William Ward, was crucial to Morland's financial success and widespread fame. Prints after his paintings were immensely popular and affordable, making his art accessible to a much wider audience than original oil paintings alone could reach. He understood the market value of reproducible images and often painted subjects with the print market in mind.

He also collaborated directly with publishers. For instance, he worked with John Harris on producing drawing books, such as Sketches by G. Morland (published 1793-99), intended for amateur artists. However, his popularity also led to problems. Unauthorized copies and forgeries of his work became rampant, both in painting and print form. Morland was forced to issue public notices warning against fraudulent reproductions, highlighting the commercial pressures and pitfalls associated with his level of fame in the burgeoning art market of the time.

A Life of Excess, Debt, and Decline

Despite the considerable income generated by his art, Morland's personal life was chaotic. He developed a reputation for extravagance, carousing, and heavy drinking. He frequented taverns and associated with a wide circle of acquaintances, from fellow artists to boxers and tradesmen, often neglecting his work or painting rapidly only when pressed by financial need. His lifestyle led to chronic indebtedness.

He was constantly pursued by creditors, forcing him to move frequently and sometimes go into hiding, such as his stint on the Isle of Wight. His productivity remained high, partly because he needed to paint constantly to pay off debts or secure advances from dealers, often at disadvantageous prices. Anecdotes abound of him painting canvases in taverns to settle his bills. This relentless pressure inevitably affected the quality of his work, especially in his later years, leading to repetition of subjects and sometimes hasty execution.

In 1799, his debts finally caught up with him, and he was arrested and confined to the King's Bench Prison, a debtors' prison in London. He continued to paint while incarcerated, finding a ready market even there. He was eventually released in 1802 under the Insolvent Debtors Act, but his freedom was short-lived, and his health had been severely compromised by years of alcoholism and stress.

Final Years and Untimely Death

Morland's final years were marked by declining health and continued financial struggles. Though released from prison, he never regained his former vigour or the peak quality of his earlier work. On October 19, 1804, while in a sponging-house (a holding place for debtors) in Clerkenwell, London, he suffered a seizure or stroke, described at the time as "brain fever." He lost consciousness and died a few days later on October 29, 1804, at the tragically young age of 41. His devoted wife, Anne, who had endured much throughout their turbulent marriage, was reportedly so devastated by his death that she died just three days later. They were buried together.

Legacy and Influence

George Morland left behind an enormous body of work, estimated at over 4,000 paintings and countless drawings, though attribution remains complex due to the number of copies and imitations. His immediate influence was significant, particularly on painters of rural genre and animal subjects. His accessible style and popular themes ensured his work was widely known and emulated. Artists like James Ward, his brother-in-law, developed their own distinct style but clearly engaged with Morland's subject matter. The rustic realism in the early works of J.M.W. Turner might also show a passing awareness of Morland's popular scenes.

However, Morland's critical reputation fluctuated after his death. During the Victorian era, his often unvarnished depictions of low life and his own dissolute biography perhaps fell out of favour compared to more morally uplifting or sentimentally refined art. His immense productivity also led to perceptions of unevenness, with his finest works sometimes overshadowed by weaker, rapidly produced canvases.

It was not until the later 20th century that his work received renewed critical and scholarly attention. Exhibitions and publications began to reassess his contribution, recognizing his technical skill, his importance in the development of British genre painting, his role in popularizing rural themes, and the significance of his anti-slavery works. Today, he is acknowledged as a major figure of his time, albeit a flawed one. His paintings are held in numerous major collections, including the National Gallery, Tate Britain, the Wallace Collection in London, the Louvre in Paris, and many regional UK museums.

Conclusion

George Morland's life and art present a compelling paradox. He was an artist of exceptional natural talent, capable of producing works of great charm, sensitivity, and atmospheric power. His depictions of English rural life defined a genre and achieved phenomenal popularity, shaping public perceptions of the countryside. Yet, his personal demons – alcoholism and chronic debt – constantly undermined his potential and ultimately destroyed him. His legacy is thus twofold: a body of work that offers a vivid, often affectionate, portrayal of late Georgian England, and a cautionary tale of genius compromised by self-destructive habits. As a chronicler of the stables, taverns, and cottages of his time, and briefly as a voice against injustice, Morland secured a unique and enduring place in British art history.