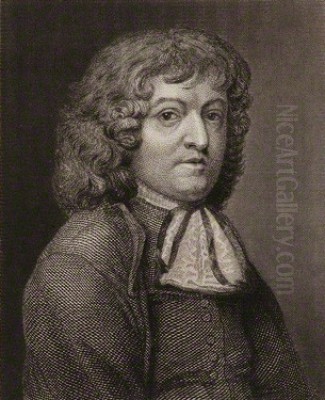

Samuel Cooper, often hailed as the greatest English miniaturist of all time, stands as a pivotal figure in the history of British art. Working during the tumultuous 17th century, a period marked by civil war, regicide, the Interregnum, and the Restoration of the monarchy, Cooper's art provides an intimate and psychologically profound record of the era's most prominent personalities. His ability to capture not just a likeness but the very character and soul of his sitters, all within the demanding confines of the miniature, set him apart from his predecessors and contemporaries, earning him an international reputation and the admiration of patrons from across the political spectrum.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Samuel Cooper was born in London around 1609, into a family with artistic connections. His uncle was the esteemed miniaturist John Hoskins the Elder (c. 1590–1665), who became his master and under whose tutelage Cooper honed his prodigious talents. John Hoskins himself was a significant figure, transitioning the art of miniature painting from the more linear, decorative style of the Elizabethan and Jacobean eras towards a greater naturalism and psychological depth, influenced by the broader trends in European Baroque portraiture.

Working in Hoskins's studio, Samuel, alongside his brother Alexander Cooper (1609–1660), who also became a miniaturist of note, would have been immersed in the techniques and traditions of the art form. Early English miniature painting was dominated by figures like Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547–1619) and his pupil Isaac Oliver (c. 1565–1617). Hilliard, limner to Queen Elizabeth I and James I, was celebrated for his jewel-like, exquisitely detailed portraits that emphasized linearity and rich ornamentation, often imbued with complex symbolism. Oliver, of Huguenot descent, introduced a greater sense of three-dimensionality and chiaroscuro, influenced by continental art, and his work often displayed a more melancholic and introspective mood.

While Cooper undoubtedly learned from the legacy of Hilliard and Oliver, likely through Hoskins who had himself absorbed their influence, his own artistic vision soon diverged. He moved beyond their more formal and sometimes idealized representations, developing a style characterized by an unprecedented realism, a painterly freedom, and a remarkable ability to convey the sitter's inner life. His early works, though sometimes difficult to distinguish from those of Hoskins, already show signs of this burgeoning talent for capturing character with a striking immediacy.

It is believed that Cooper traveled to the continent, possibly visiting France and the Netherlands, in the 1630s or early 1640s. Such travels would have exposed him to a wider range of artistic styles and influences. In the Netherlands, he might have encountered the powerful realism and psychological acuity of artists like Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) and Frans Hals (c. 1582/83–1666), whose portraits were renowned for their vitality. In France, the art of miniature was also flourishing, with artists like Jean Petitot (1607–1691) achieving fame for his exquisite enamel miniatures. These experiences likely broadened Cooper's artistic horizons and reinforced his inclination towards a more robust and psychologically penetrating style of portraiture.

The Development of a Unique Style

Samuel Cooper's mature style, which began to fully emerge by the 1640s, was revolutionary for its time within the realm of miniature painting. He eschewed the elaborate backgrounds and symbolic accoutrements that often featured in earlier miniatures, preferring instead plain, dark backgrounds. This allowed the viewer's entire attention to be focused on the face and character of the sitter. His use of chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and shadow – was masterful, sculpting the features with a sense of volume and presence rarely seen before in miniatures.

Unlike the often flat, linear approach of Hilliard, Cooper's technique was more painterly, employing visible brushstrokes that contributed to the vibrancy and texture of the likeness. He had an uncanny ability to render the nuances of human flesh, the glint in an eye, the subtle curve of a lip, or the weariness etched into a face. This was not mere verisimilitude; it was a profound engagement with the individual, capturing fleeting expressions and hinting at the complexities of their personality. His sitters appear as living, breathing individuals, often with a startling directness in their gaze.

The diary of John Evelyn, a contemporary connoisseur, records a visit to Cooper in 1662 where he praised the miniaturist's work, noting its power and comparing it favorably to the large-scale oil portraits of the day. This was a significant acknowledgment, as miniatures were sometimes seen as a lesser art form. Cooper, however, elevated the miniature to a level of artistic seriousness and psychological depth that rivaled the best of contemporary oil portraiture. His works were not just precious keepsakes but powerful statements of identity and character.

His palette, while sometimes rich, was often subtly modulated to enhance the realism of the flesh tones and the textures of hair and fabric. He typically worked on vellum laid down on card, or sometimes on prepared chicken skin, using watercolour and gouache with extraordinary skill. The scale, often no more than a few inches high, makes his achievement all the more remarkable. To convey such depth of character and painterly richness on such a small surface required immense technical control and artistic vision.

Navigating a Turbulent Era: The Commonwealth Period

The English Civil War (1642–1651) and the subsequent Interregnum (1649–1660) presented both challenges and opportunities for artists. The traditional sources of royal patronage disappeared with the execution of King Charles I in 1649. However, new leaders emerged, and they too sought to have their likenesses recorded. Samuel Cooper, with his growing reputation for incisive portraiture, found himself in demand among the figures of the Commonwealth.

His most famous sitter from this period was undoubtedly Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658), the Lord Protector. Cooper painted Cromwell on several occasions, producing what are considered the most definitive and psychologically compelling portraits of this complex and powerful leader. The most celebrated of these is the unfinished miniature of Cromwell from around 1656, now in the collection of the Duke of Buccleuch. This portrait is a masterpiece of unvarnished realism. Cromwell is depicted "warts and all," a phrase reputedly originating from his own instruction to Cooper to paint him as he truly was, without flattery.

The Buccleuch miniature shows Cromwell with a rugged, careworn face, his expression stern yet tinged with a hint of melancholy. The modeling of the features is incredibly strong, the flesh tones convincing, and the gaze intense. Cooper captures the authority and the burden of leadership in this small image. Another notable portrait of Cromwell by Cooper, dated 1653, was used by Thomas Simon (c. 1618–1665), the chief engraver to the Mint, for the Protectorate coinage and medals, demonstrating the official status and wide dissemination of Cooper's likenesses.

During the Commonwealth, Cooper also painted other prominent figures, including members of Cromwell's family and leading Parliamentarians. His ability to navigate the shifting political landscape and maintain a diverse clientele speaks to the universal appeal of his artistic skill. He was not merely a court painter tied to one faction but an artist whose talent was recognized and sought after by individuals across the political divide. This period solidified his reputation as the preeminent miniaturist in England. His portraits from this era are invaluable historical documents, offering a glimpse into the personalities who shaped one of England's most transformative periods.

The Restoration and Royal Favor

The restoration of the monarchy in 1660 with King Charles II (1630–1685) brought about another significant shift in the cultural and political climate of England. Charles II's court was known for its glamour, sophistication, and a more relaxed moral atmosphere compared to the austerity of the Commonwealth. Samuel Cooper, despite his association with Cromwell and other Parliamentarian figures, successfully transitioned his career into this new era, quickly gaining royal favor.

Charles II, a keen connoisseur of the arts, recognized Cooper's exceptional talent. The King himself sat for Cooper on multiple occasions, and the artist was appointed "King's Limner" in 1663, a prestigious position that affirmed his status as the leading miniaturist of the realm. His portraits of Charles II capture the monarch's characteristic charm, intelligence, and perhaps a hint of his famous cynicism. These royal portraits were often replicated and disseminated, serving as important tools of royal image-making.

Cooper also painted many other members of the royal family and the court circle. Among his most celebrated sitters from this period was Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland (1640–1709), one of Charles II's most influential mistresses. Cooper's portraits of her convey her renowned beauty and formidable personality. He also painted James Scott, Duke of Monmouth (1649–1685), Charles II's illegitimate son, and other prominent courtiers and ladies of fashion.

His style during the Restoration period retained its characteristic psychological depth and painterly quality, but perhaps adapted subtly to the more flamboyant tastes of the new court. There is often a greater emphasis on the richness of costume and the elegance of the sitter, reflecting the prevailing courtly aesthetic influenced by continental artists like Sir Peter Lely (1618–1680), who became the dominant oil painter of the Restoration court. Lely, of Dutch origin, had succeeded Sir Anthony van Dyck (1599–1641) as the leading portraitist in oils, and his opulent style set the tone for much of Restoration portraiture. Cooper's miniatures, while distinct, existed within this broader artistic context.

Samuel Pepys, the famous diarist, provides valuable contemporary accounts of Cooper and his work. Pepys visited Cooper's studio and commissioned a miniature of his wife, Elizabeth. He marveled at Cooper's skill, noting the lifelike quality of his portraits and the high prices they commanded, a testament to Cooper's success and reputation. Pepys's diary entries offer a vivid glimpse into the world of a highly sought-after artist in Restoration London. Cooper resided in Covent Garden, then a fashionable district, and his studio was a hub for the elite seeking to have their likenesses immortalized by his hand.

Masterpieces and Signature Works

Throughout his career, Samuel Cooper produced a remarkable body of work, with several pieces standing out as iconic representations of their subjects and as pinnacles of the art of miniature painting.

The aforementioned unfinished portrait of Oliver Cromwell (c. 1656, Duke of Buccleuch Collection) is arguably his most famous work. Its raw, unidealized depiction, combined with profound psychological insight, makes it a landmark in British portraiture. The directness of Cromwell's gaze and the subtle modeling of his weathered face are rendered with astonishing skill. Its unfinished state, particularly the loosely sketched body, only serves to concentrate the viewer's attention on the powerfully realized head.

His portraits of King Charles II are also significant. One notable example is the miniature of Charles II in Garter robes (c. 1660-1665, Royal Collection). Here, Cooper combines his characteristic realism in the depiction of the King's face – with its heavy-lidded eyes and distinctive features – with a rich rendering of the ceremonial attire. This work effectively conveys both the individual and the monarch.

The portrait of Barbara Villiers, Duchess of Cleveland (c. 1665, Royal Collection), is another masterpiece. Cooper captures her celebrated allure, with a soft modeling of her features and an expressive rendering of her eyes and mouth. The luxuriousness of her attire and jewels is depicted with a painterly touch, avoiding excessive detail in favor of overall effect.

A particularly striking male portrait is that of George Monck, 1st Duke of Albemarle (c. 1660, National Portrait Gallery, London). Monck was a key figure in the Restoration, and Cooper portrays him with a rugged, soldierly appearance, his expression conveying determination and authority. The handling of the armor and the strong characterization of the face are typical of Cooper's powerful style.

Other important works include portraits of John Thurloe, Cromwell's Secretary of State; Margaret Lemon, reputedly Van Dyck's mistress, in an allegorical guise (though attribution of this subject has been debated); and various members of the English aristocracy and gentry. Each miniature, regardless of the sitter's status, reveals Cooper's consistent ability to penetrate beyond the surface and capture a sense of living presence. His oeuvre provides a veritable gallery of the leading figures of 17th-century England.

Technique and Materials

Samuel Cooper's technical mastery was fundamental to his artistic success. He typically painted on vellum, a fine parchment made from animal skin, which was usually laid down on a piece of card (often a playing card) for support. While ivory became a popular support for miniaturists later in the 17th and 18th centuries, particularly with artists like Jean Petitot for enamels or later watercolourists like Richard Cosway (1742–1821) and Ozias Humphry (1742–1810), vellum was the standard for watercolour miniatures in Cooper's time.

He used water-based pigments, a combination of transparent watercolour and opaque gouache (bodycolour). His application of paint was remarkably fluid and confident. He built up the flesh tones with subtle layers of colour, using fine stippling (dots) and hatching (parallel lines) to model the forms, particularly in the face. However, his technique was less reliant on meticulous, almost invisible stippling than some of his predecessors like Hilliard or Oliver. Instead, Cooper often allowed his brushstrokes to remain visible, contributing to the painterly texture and vitality of his work. This more expressive handling of paint was a hallmark of his style and distinguished him from the tighter, more linear approach of earlier miniaturists.

His understanding of light and shadow was exceptional. He used chiaroscuro not just for dramatic effect but to give a convincing sense of three-dimensionality to the head and to highlight the psychological focal points of the face, such as the eyes and mouth. The backgrounds were usually kept simple, often a dark, graduated wash, which helped to project the figure forward and concentrate attention on the sitter's features.

The scale of his works, typically oval and only a few inches in height, demanded incredible precision. Yet, despite the small size, his portraits possess a monumentality and psychological weight that belies their physical dimensions. This ability to achieve such power on a miniature scale is one of the defining characteristics of his genius. His tools would have included fine brushes made from sable or squirrel hair, and possibly a magnifying glass, though the fluency of his brushwork suggests a remarkable directness of vision and execution.

Cooper and His Contemporaries

Samuel Cooper's career unfolded within a rich and evolving artistic landscape in England and Europe. His primary artistic lineage was through his uncle and master, John Hoskins the Elder, who himself was a bridge between the Elizabethan tradition of Nicholas Hilliard and Isaac Oliver and the more Baroque sensibilities emerging in the 17th century. Cooper's own brother, Alexander Cooper, also pursued a career as a miniaturist, working for Queen Christina of Sweden and other European courts, indicating the international reach of this art form.

In the broader field of English portraiture, the towering figure of Sir Anthony van Dyck cast a long shadow. Van Dyck, who worked in England from 1632 until his death in 1641, revolutionized English oil portraiture with his elegant, aristocratic style and psychological insight. While Cooper worked in a different medium, he would have been acutely aware of Van Dyck's influence, and it is likely that Van Dyck's sophisticated approach to characterization resonated with Cooper's own artistic aims. Indeed, some scholars have noted a "Van Dyckian" elegance in some of Cooper's female portraits.

During the Interregnum, when royal patronage was absent, artists like Robert Walker (1599–1658) became prominent for their portraits of Parliamentarian leaders, including Cromwell. Walker's style was somewhat sterner and more republican in feel than Van Dyck's courtly manner. Cooper's portraits of Cromwell, while sharing a similar directness, possess a greater psychological depth and painterly refinement.

With the Restoration, Sir Peter Lely became the dominant force in oil portraiture, his studio producing a vast number of portraits of the court and aristocracy. Lely's style was opulent and somewhat formulaic, emphasizing sensuousness and courtly grace. Cooper's miniatures from this period, while reflecting the fashionable attire and hairstyles, maintained their focus on individual character, providing a more intimate counterpoint to Lely's grander statements. Other oil painters of note during Cooper's later career included John Michael Wright (c. 1617–1694), whose work often showed a more sober realism.

Among fellow miniaturists, Cooper was largely without peer in England during his mature period. Artists like David des Granges (1611–c. 1672) and Thomas Flatman (1635–1688), a poet and miniaturist, were also active, but Cooper's reputation far surpassed theirs. Later miniaturists such as Richard Gibson (1615–1690), known as "Dwarf Gibson," who was a page to Queen Henrietta Maria and later worked for Charles II and James II, and Peter Cross (or Crosse) (c. 1645–1724), continued the tradition, but Cooper remained the benchmark against whom others were measured.

On the continent, Cooper's work was known and admired. His travels would have brought him into contact with artistic developments in France and the Netherlands. The Dutch artist Pieter Nason (c. 1612–c. 1688/90), who worked in The Hague and was known for his refined portraits, has been cited as a possible influence or parallel figure. In France, enamel miniaturists like Jean Petitot and Louis Du Guernier (1614-1659) were highly esteemed, though their technique and aesthetic differed from Cooper's watercolour on vellum.

International Connections and Reputation

Samuel Cooper's fame was not confined to England. His travels abroad in his earlier years, likely to France and the Low Countries, would have helped establish his name on the continent. The quality of his work spoke for itself, and his ability to capture a striking likeness with such psychological depth was a rare talent that transcended national borders.

His brother, Alexander Cooper, spent much of his career working abroad, notably for Queen Christina of Sweden, and also in Denmark and the Netherlands. This family connection might have further facilitated Samuel's reputation in European artistic circles. While Samuel primarily worked in England, his sitters sometimes included foreign dignitaries or individuals with international connections, further spreading his fame.

The very nature of miniatures – small, portable, and often exchanged as personal gifts or diplomatic tokens – meant that his works could travel easily. A miniature by Cooper was a highly prized possession, valued not only for its artistic merit but also as an intimate record of an individual. His patrons included some of the most powerful and influential people of his time, and their appreciation for his work would have been communicated within their elite networks, which often extended across Europe.

Contemporaries like John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys, whose writings reflect the high esteem in which Cooper was held, were part of a sophisticated, cosmopolitan milieu that valued artistic excellence. Evelyn, in particular, was well-traveled and a noted connoisseur, and his praise for Cooper, comparing his miniatures favorably to large-scale oil paintings, indicates the artist's standing. The fact that Cooper could command high prices for his work, as Pepys noted, also attests to his significant reputation. While it is difficult to trace the full extent of his international influence directly, the superlative quality of his art ensured that he was recognized as a master of his craft far beyond the shores of England.

Later Life, Death, and Legacy

Samuel Cooper continued to work prolifically throughout the 1660s and into the early 1670s, maintaining his position as the preeminent miniaturist in England. His studio in Covent Garden remained a fashionable destination for those seeking the finest quality portrait miniatures. He was not only a supremely gifted artist but also a cultured individual, reportedly a skilled musician and fluent in French, which would have facilitated his interactions with a sophisticated clientele.

Samuel Cooper died in London on May 5, 1672, at the age of about 63. He was buried in the old St Pancras Churchyard, a site that would later become the resting place for other notable figures. His death was noted by his contemporaries as a significant loss to the art world. His wife, Christiana, was the sister of Alexander Pope's mother, linking him by marriage to another prominent figure in English cultural history, albeit of a later generation.

Cooper's legacy was immediate and enduring. He had set a new standard for miniature painting, emphasizing psychological realism and painterly technique. His influence can be seen in the work of subsequent generations of miniaturists, though few could match his profound ability to capture character. Artists like Lawrence Crosse (c. 1650–1724) and Bernard Lens III (1682–1740) continued the tradition of miniature painting in England, but the art form gradually evolved, with ivory becoming the preferred support and styles changing with the prevailing tastes of the 18th century.

Today, Samuel Cooper's works are treasured in major public and private collections worldwide, including the Royal Collection Trust, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, the National Portrait Gallery in London, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, and the collection of the Duke of Buccleuch. His miniatures are not only exquisite works of art but also invaluable historical documents, providing an intimate and compelling visual record of the leading personalities of a dramatic era in English history. He remains, by common consensus, the "Van Dyck of the miniature," a master whose work continues to fascinate and impress with its technical brilliance and profound humanity.

Conclusion

Samuel Cooper's contribution to British art and the specific discipline of miniature painting is immense. He elevated the art of the limner from a craft often focused on decorative likeness to a high art capable of profound psychological expression. Working through periods of intense political upheaval, he created a gallery of portraits that offer unparalleled insight into the characters of kings, protectors, courtiers, and revolutionaries. His mastery of chiaroscuro, his painterly freedom, and his uncanny ability to convey the inner life of his sitters within the compass of a few inches set him apart. More than three centuries after his death, Samuel Cooper's miniatures retain their power to connect us directly and intimately with the people who shaped one of the most fascinating periods in history, securing his place as one of the true giants of portraiture.