Gerard van Spaendonck stands as a pivotal figure in the history of floral painting, a Dutch artist who masterfully blended the rich traditions of his homeland with the refined elegance of late 18th and early 19th-century Paris. His work not only captivated audiences with its botanical accuracy and aesthetic beauty but also played a significant role in the education of a subsequent generation of botanical artists. His life and career offer a fascinating glimpse into the artistic and scientific worlds of a transformative era in European history.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in the Netherlands

Born in Tilburg, in the Dutch province of North Brabant, on March 22, 1746, Gerard van Spaendonck (christened Gerardus) was destined for a life immersed in art. His family background was respectable; his father, Jan Anthonie van Spaendonck, served as a steward or bailiff to the local lord of Tilburg and Goirle, suggesting a comfortable upbringing. This environment likely provided young Gerard with the stability and perhaps the initial encouragement to pursue his burgeoning artistic talents.

From a young age, Spaendonck exhibited a remarkable aptitude for drawing and painting. Anecdotal evidence suggests that his talent was recognized early, with stories of him earning pocket money through his artistic endeavors even as a child. One such account describes him being regularly taken from his duties in his father's office to dedicate time to drawing, a clear indication of his precocious skill and the support he received. This early immersion in art laid a crucial foundation for his later, more formal training.

To hone his innate abilities, Spaendonck was sent to Antwerp in the 1760s. There, he studied under the guidance of Guillaume-Jacques Herreyns (also known as Willem Jacob Herreyns). Herreyns was a respected Flemish painter, known for his historical scenes, portraits, and decorative works, operating in a style that bridged the late Baroque and emerging Neoclassical sensibilities. Under Herreyns, Spaendonck would have received a thorough grounding in academic drawing, composition, and painting techniques, skills that would prove invaluable throughout his career, even as he specialized in a different genre.

The Parisian Ascent: From Royal Miniaturist to Botanical Professor

In 1769, at the age of 23, Gerard van Spaendonck made the pivotal decision to move to Paris. This was a bold step, as Paris was the undisputed artistic capital of Europe, teeming with talent and fierce competition. However, it was also a city of immense opportunity for an artist of his caliber. His Dutch training, with its emphasis on meticulous observation and detailed rendering, particularly in still life, found a receptive audience in France.

His initial years in Paris saw him gain recognition for his exquisite miniature paintings. These small, detailed works, often portraits, were highly fashionable. His skill in this demanding medium soon attracted high-profile patrons. By 1774, his reputation had grown to such an extent that he was appointed miniaturist to King Louis XVI. This royal appointment was a significant honor and provided him with considerable prestige and access to influential circles. It was during this period that he likely formed connections with figures such as the Comte de La Billarderie d'Angiviller, who was the Director-General of the Bâtiments du Roi and played a key role in royal artistic patronage.

Spaendonck's talents, however, extended far beyond miniatures. His true passion and greatest skill lay in the depiction of flowers. His floral still lifes, which combined Dutch precision with a lighter, more graceful French aesthetic, began to attract considerable attention. This expertise led to another prestigious appointment in 1774 (some sources state 1780 or 1781 for the professorship, but his association began earlier): he became Professor of Floral Painting at the Jardin du Roi (the Royal Garden). This institution, founded in the 17th century, was a leading center for botanical research and education.

The position at the Jardin du Roi was perfectly suited to Spaendonck's talents. It allowed him to immerse himself in the study of plants, working directly from nature. He had access to a vast collection of exotic and common species, which he rendered with unparalleled accuracy and artistry. His role was not merely to paint but also to teach, and he would become an influential mentor to a new generation of botanical artists.

A Master's Touch: Artistic Style and Techniques

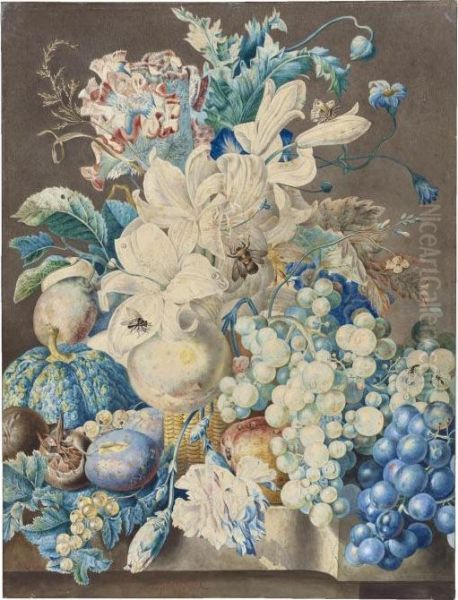

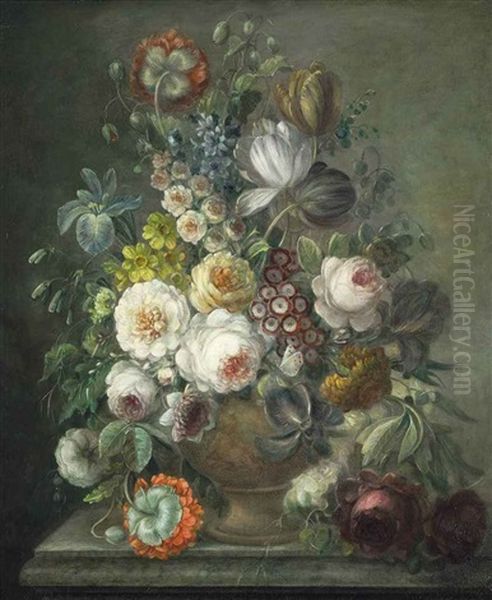

Gerard van Spaendonck's artistic style is a harmonious fusion of Dutch meticulousness and French elegance. He inherited the legacy of the great Dutch Golden Age flower painters of the 17th century, such as Jan Davidsz. de Heem, Rachel Ruysch, and particularly Jan van Huysum, who was renowned for his luminous, detailed, and often opulent floral arrangements. Like these predecessors, Spaendonck paid extraordinary attention to botanical accuracy, rendering each petal, leaf, stem, and even the occasional insect with scientific precision.

However, Spaendonck's work also reflects the prevailing tastes of late 18th-century France. While maintaining Dutch realism, his compositions often possess a lighter, more airy quality, and a refined grace that aligns with French Rococo and early Neoclassical aesthetics. He moved away from the sometimes-heavy symbolism of earlier Dutch still lifes, focusing more on the inherent beauty and decorative qualities of the flowers themselves.

His command of color was exceptional. He employed a rich and vibrant palette, capturing the subtle gradations of hue in a rose petal or the velvety texture of an iris. His brushwork was incredibly fine and controlled, allowing him to depict the delicate translucency of petals and the dewy freshness of his subjects. He often arranged his flowers in elegant vases, placed on marble ledges, a common motif that added a sense of classical stability and provided a contrasting texture to the organic forms of the flora. These compositions were typically well-balanced, often employing a pyramidal or S-curve structure to create a sense of dynamic harmony.

Spaendonck was versatile in his choice of media. While renowned for his oil paintings, he was also a master of watercolor and gouache, particularly on vellum. These media allowed for exceptional detail and luminosity, ideal for botanical illustration. His skill in miniature painting, often on ivory, also showcased his ability to work with exacting precision on a small scale.

Celebrated Works and the "Fleurs dessinées d'après nature"

While specific titles of many individual easel paintings can be generic, such as "Still Life with Flowers in a Vase" or "Flower Piece," his oeuvre is consistently characterized by its high quality and distinctive style. His paintings often feature a diverse array of flowers, including roses, tulips, peonies, irises, poppies, and carnations, sometimes accompanied by fruits or symbolic elements like a bird's nest or insects, which added life and a touch of trompe-l'œil realism. Works like Flowers in an Alabaster Vase or Vase of Flowers with a Bird's Nest on a Marble Ledge are representative of his output, showcasing his compositional skill and exquisite rendering of textures.

Perhaps his most influential and widely disseminated work was not a single painting but a collection of engravings titled Fleurs dessinées d'après nature (Flowers Drawn from Nature). Published in parts between 1799 and 1801 (though work on it began earlier), this series consisted of twenty-four stipple engravings, many colored by hand à la poupée (a technique where multiple colors are applied to a single plate). These prints were intended as models for students of flower painting and botanical illustration, demonstrating various species and compositional approaches.

The Fleurs dessinées d'après nature was a landmark publication. It combined artistic beauty with scientific accuracy, making it an invaluable resource. The plates were engraved by various artists under Spaendonck's direct supervision, including his pupil P. F. Le Grand. The quality of these engravings set a new standard for botanical illustration and cemented Spaendonck's reputation as a leading authority in the field. They were highly sought after and remain prized by collectors and institutions today.

A Professor and His Protégés: Shaping the Next Generation

Gerard van Spaendonck's role as Professor of Floral Painting at the Jardin du Roi (which, after the French Revolution, was reorganized in 1793 as the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, where he continued as Professor of Botanical Iconography) was arguably as important as his personal artistic output. He was a dedicated and influential teacher, shaping the careers of several prominent artists who followed in his footsteps.

His most famous pupil was undoubtedly Pierre-Joseph Redouté. Often dubbed the "Raphael of Flowers," Redouté learned watercolor techniques, particularly stipple engraving for color printing, from Spaendonck. While Redouté would go on to achieve immense fame, particularly for his depictions of roses and lilies for Empress Josephine, his foundational training under Spaendonck was crucial to his development. Spaendonck's emphasis on direct observation and botanical accuracy, combined with artistic finesse, profoundly influenced Redouté's approach.

Other notable students included Pancrace Bessa, who also became a distinguished botanical artist and illustrator, working in a style similar to Redouté and contributing to important botanical publications. Antoine Chazal, another pupil, excelled in flower and animal painting and also taught at the Muséum. Jan Frans van Dael, a Flemish contemporary active in Paris, though perhaps not a direct student in the formal sense, worked in a similar vein and was part of the same artistic circle, specializing in lush flower and fruit still lifes. The influence of Spaendonck's teaching and his published works extended to many other aspiring botanical artists of the period.

His pedagogical approach emphasized drawing directly from nature (d'après nature), a principle central to the scientific and artistic mission of the Jardin du Roi and later the Muséum. He encouraged his students to capture not just the appearance but also the "character" of each plant.

Navigating the Revolution: Resilience and Connections

The late 18th century was a period of immense upheaval in France, culminating in the French Revolution (1789-1799). This tumultuous era posed challenges and dangers for many, particularly those associated with the Ancien Régime. Spaendonck, as a former miniaturist to Louis XVI and a figure within royal institutions, might have found himself in a precarious position.

However, he managed to navigate these turbulent times successfully. His position at the Jardin du Roi, which transformed into the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, likely helped, as scientific and educational institutions were often seen as valuable to the new Republic. Furthermore, he had influential friends. One notable anecdote recounts how the renowned Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David, a powerful figure during the Revolution, intervened to protect Spaendonck. According to the story, Spaendonck was invited to a banquet that turned out to be a trap or a politically dangerous gathering. David, recognizing the peril, managed to ensure Spaendonck's safety, possibly saving him from arrest or even the guillotine.

This period also saw him cultivate friendships and patronage from new quarters. For instance, he maintained a friendship with a French nobleman named Lavalle (possibly the Comte de Lavallette), who admired his miniature works and provided some financial support or commissions. Despite the political turmoil, Spaendonck continued to work and teach, adapting to the changing social and political landscape. His art, focused on the timeless beauty of nature, perhaps offered a welcome respite from the uncertainties of the era.

Family Ties and Artistic Collaborations

Gerard van Spaendonck was not the only artist in his family. His younger brother, Cornelis van Spaendonck (1756-1839), also became a painter, specializing in flower pieces and porcelain painting. Cornelis followed Gerard to Paris and also achieved considerable success. He worked for the Sèvres porcelain manufactory for a period, designing floral decorations.

The two brothers sometimes collaborated, and their styles could be quite similar, occasionally leading to difficulties in attribution for works not clearly signed. Both shared the Dutch heritage of meticulous detail and a love for floral subjects. However, Gerard is generally considered the more innovative and influential of the two, particularly due to his teaching role and his groundbreaking Fleurs dessinées d'après nature. Their shared artistic pursuits undoubtedly created a supportive familial bond within the competitive Parisian art world.

Contemporaries and the Wider Artistic Milieu

Gerard van Spaendonck operated within a vibrant artistic community in Paris. Beyond his direct students, he would have been aware of, and interacted with, numerous other artists. In the realm of still life and flower painting, Anne Vallayer-Coster was a prominent contemporary, a highly respected female artist who also enjoyed royal patronage and specialized in rich floral and still life compositions.

The broader art scene was dominated by Neoclassicism, championed by figures like Jacques-Louis David. While Spaendonck's genre was different, the prevailing emphasis on clarity, order, and naturalism in Neoclassicism may have resonated with his own pursuit of botanical accuracy. Portraitists like Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, who painted Queen Marie Antoinette and other members of the aristocracy, were also major figures.

In the tradition of still life, the legacy of Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin, who had died in 1779, still loomed large, his intimate and masterfully painted scenes of everyday objects setting a high bar for realism and painterly quality. While Spaendonck's floral works were more decorative and often more opulent than Chardin's humble subjects, Chardin's influence on French still life painting was pervasive. Earlier French flower painters like Jean-Baptiste Monnoyer had also established a strong tradition of decorative floral art in France, upon which Spaendonck and his contemporaries built.

His connections also extended to the scientific community through his work at the Jardin du Roi/Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle. He collaborated with botanists and naturalists, his art serving both aesthetic and scientific purposes. His work was integral to the cataloging and understanding of plant species, bridging the gap between art and science.

Honors, Later Years, and Enduring Legacy

Gerard van Spaendonck's contributions to art and science were widely recognized during his lifetime. In 1781, he was elected to the prestigious Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (which later became part of the Académie des Beaux-Arts). This was a significant mark of esteem from his peers. He exhibited regularly at the Paris Salon, where his works were admired for their beauty and technical brilliance.

After the Revolution, under Napoleon, he continued to receive honors. In 1804, he was appointed one of the first administrators of the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, a testament to his standing in both the artistic and scientific communities. In 1805, he was awarded the Legion of Honour by Napoleon Bonaparte, a further indication of his esteemed position in French society. He may have even painted a miniature portrait of Napoleon, given his earlier renown as a miniaturist.

Gerard van Spaendonck continued to paint and teach into his later years. He died in Paris on May 11, 1822, at the age of 76. He was buried in the Père Lachaise Cemetery, the final resting place of many notable figures.

His legacy is multifaceted. As an artist, he produced a body of work that stands among the finest examples of floral painting, admired for its exquisite detail, vibrant color, and elegant composition. He successfully revitalized and adapted the Dutch floral tradition for a French audience, influencing the course of still life painting in the late 18th and early 19th centuries.

As an educator, his impact was profound. Through his teaching at one of Europe's premier botanical institutions and through his influential publication Fleurs dessinées d'après nature, he trained and inspired a generation of botanical artists, most notably Pierre-Joseph Redouté, ensuring the continuation and development of high-quality botanical illustration. His work helped to elevate the status of flower painting, demonstrating that it could be both scientifically accurate and aesthetically sublime.

Today, Gerard van Spaendonck's paintings and prints are held in major museums and private collections around the world, including the Louvre in Paris, the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge. They continue to be celebrated for their timeless beauty and serve as a testament to an artist who dedicated his life to capturing the ephemeral splendor of the floral world with unparalleled skill and devotion. He remains a key figure for understanding the intersection of art, science, and education at a pivotal moment in European cultural history.