Introduction: A Pivotal Figure in Renaissance Art

Giulio Romano stands as one of the most significant figures bridging the High Renaissance and the ensuing Mannerist period in Italian art. Born Giulio Pippi, and often identified by his birthplace as Giulio Romano, he was not merely a painter but also a highly accomplished architect and designer. His career began under the immense shadow of Raphael, whose principal pupil and artistic heir he became. Yet, Giulio forged his own distinct path, developing a style that, while rooted in the classical harmony of his master, embraced complexity, artifice, and emotional intensity, characteristics that would define Mannerism. His influence extended far beyond Rome and Mantua, shaping artistic trends across Italy and even into France. Understanding Giulio Romano is key to understanding the transition and evolution of art in the tumultuous, yet creatively fertile, 16th century.

Name, Birth, and Early Identity

The artist known to history as Giulio Romano was baptised Giulio di Pietro de' Giannuzzi. The name "Pippi" appears to be a family nickname or patronymic that became closely associated with him, often cited as Giulio Pippi. However, like many artists of his time, he became most widely known by a toponymic surname indicating his origin: "Romano," meaning "the Roman." This designation highlighted his connection to the artistic epicenter where he received his training and first achieved fame.

His precise birth year remains a subject of scholarly debate, a common issue for artists of this period due to inconsistent record-keeping. The biographer Giorgio Vasari, a near-contemporary, suggested a birth year around 1492. However, substantial evidence, including documents related to his early career and development, points more strongly towards a later date, likely around 1499. While 1492 persists in some older sources, modern art historical consensus generally favors the 1499 date. Regardless of the exact year, it is clear he was remarkably young when he entered the bustling workshop of Raphael. His death is firmly documented as occurring in Mantua on November 1, 1546.

Apprenticeship Under Raphael: The Roman Crucible

Giulio Romano's artistic formation took place in the most prestigious workshop in Rome, that of Raphael Sanzio. Entering the studio probably in his early teens, Giulio quickly distinguished himself through his talent and diligence, becoming one of Raphael's most trusted assistants. The workshop was a collaborative environment, tackling vast papal commissions and private projects, demanding efficiency and stylistic consistency. Giulio absorbed Raphael's grace, compositional clarity, and idealized beauty, mastering the High Renaissance idiom.

He collaborated closely with Raphael and other assistants, such as Gianfrancesco Penni (known as "Il Fattore"), on major projects. His hand is identifiable in sections of the Vatican Stanze, particularly in the later rooms like the Stanza dell'Incendio di Borgo. He learned not only painting techniques but also Raphael's methods of design, workshop management, and interaction with powerful patrons. This period was crucial, providing him with unparalleled training and access to the highest levels of artistic production in Rome.

Raphael clearly valued Giulio's abilities, increasingly entrusting him with significant portions of commissioned works. This included preparatory drawings and the execution of frescoes and panel paintings based on the master's designs. This close collaboration allowed Giulio to internalize Raphael's style so effectively that distinguishing their hands in certain works remains a challenge for art historians. His early works inevitably reflect Raphael's influence, yet hints of a more robust, energetic, and less idealized approach occasionally surface even in these formative years.

Inheriting the Mantle: After Raphael's Death

The premature death of Raphael in 1520, at the age of 37, sent shockwaves through the Roman art world and left a significant void. As Raphael's most prominent pupil, Giulio Romano, alongside Gianfrancesco Penni, inherited the workshop, its drawings, and the responsibility for completing numerous unfinished commissions. This was a pivotal moment in Giulio's career, thrusting him into a position of leadership at a relatively young age (likely just over twenty if born in 1499).

Among the most important projects left incomplete was the decoration of the Sala di Costantino in the Vatican Palace. While Raphael had conceived the overall plan and possibly designed some figures, the execution fell largely to his workshop heirs. Giulio played a dominant role, designing and painting major scenes like The Battle of the Milvian Bridge and The Vision of the Cross. These frescoes, characterized by their dynamic compositions, crowded figures, and dramatic intensity, already show Giulio moving beyond Raphael's serene classicism towards a more forceful and complex style.

He also worked to complete other projects initiated by Raphael, such as the Villa Madama, a suburban villa designed for Cardinal Giulio de' Medici (later Pope Clement VII). Though never fully realized according to the original ambitious plans conceived by Raphael and Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, Giulio contributed significantly to its structure and decoration, further honing his skills as both painter and architect. This period established him as the leading artistic force in Rome following his master's demise.

Roman Independence and the I Modi Controversy

In the years immediately following Raphael's death, Giulio Romano established himself as an independent master in Rome. He received commissions for altarpieces, devotional paintings, and portraits. Works from this period, such as the Stoning of St. Stephen for the church of Santo Stefano in Genoa (painted in Rome), showcase his developing style: powerful, muscular figures, dramatic lighting, complex poses, and a growing emphasis on emotional expression, sometimes bordering on the theatrical.

This period also saw one of the most notorious episodes of his career: his involvement with the erotic prints known as I Modi ("The Ways" or "The Positions"). Giulio created a series of explicit drawings depicting various sexual positions. These drawings were then engraved by Marcantonio Raimondi, a renowned printmaker who had frequently collaborated with Raphael. The publication of these prints caused a major scandal in papal Rome.

Raimondi was imprisoned by order of Pope Clement VII, and the prints were suppressed. The writer Pietro Aretino later composed explicit sonnets (Sonetti Lussuriosi) to accompany each image, further fueling the controversy. While Giulio himself seems to have avoided direct punishment, possibly due to his connections or by leaving Rome shortly thereafter, the incident highlighted a tension between the classical ideals often depicted in Renaissance art and a burgeoning interest in exploring more sensual, and even taboo, subject matter. It also demonstrated Giulio's willingness to push boundaries, a trait evident in his later Mannerist works.

The Call to Mantua: A New Chapter

In 1524, Giulio Romano made a decisive move that would shape the remainder of his career: he left Rome for Mantua. This relocation was facilitated by Baldassare Castiglione, the diplomat, author of The Book of the Courtier, and a friend of both Raphael and Giulio. Castiglione recommended Giulio to Federico II Gonzaga, the Marquis (later Duke) of Mantua, who was seeking a prestigious court artist to elevate the cultural standing of his city.

Mantua offered Giulio opportunities that Rome, despite its artistic richness, perhaps could not. As the principal court artist, he would have unparalleled creative freedom, consistent patronage, and the chance to work on large-scale, integrated projects encompassing architecture, painting, and decoration. Federico II Gonzaga proved to be an ambitious and appreciative patron, giving Giulio wide latitude to reshape the artistic landscape of Mantua.

Leaving Rome also distanced Giulio from the increasing political instability and the eventual Sack of Rome in 1527, which devastated the city and dispersed many artists. In Mantua, he found a secure environment where his multifaceted talents could flourish. He quickly became indispensable to the Gonzaga court, overseeing not only artistic projects but also engineering works, festival designs, and urban planning initiatives.

Architectural Dominance in Mantua: The Palazzo del Te

Giulio Romano's most celebrated achievement, and a landmark of Mannerist architecture, is the Palazzo del Te, located just outside Mantua. Commissioned by Federico II Gonzaga around 1524-1525 as a suburban villa for leisure and entertainment (the name likely derives from the area, Tejeto, shortened to "Te"), it became Giulio's magnum opus, a project where he acted as architect, interior designer, and supervisor of the extensive painted decorations executed by his workshop.

The Palazzo del Te deliberately breaks many rules of classical architecture established during the High Renaissance by architects like Donato Bramante. While using classical elements like columns, pediments, and triglyphs, Giulio employs them in unconventional and often playful ways. Features like the famous "dropped" triglyphs in the Doric frieze, oversized keystones seemingly slipping from arches, rusticated surfaces juxtaposed with smooth stucco, and intentional asymmetries create a sense of tension, surprise, and sophistication.

The building's plan is a square block around a central courtyard, with a large garden loggia extending beyond. Each facade is treated differently, avoiding simple repetition. The overall effect is one of studied artifice and intellectual wit, designed to delight and perhaps slightly unsettle the educated visitor. The Palazzo del Te perfectly embodies the Mannerist desire to move beyond classical harmony towards greater complexity, ambiguity, and self-conscious style. It remains Giulio's most enduring architectural legacy.

Painting and Decoration at the Palazzo del Te

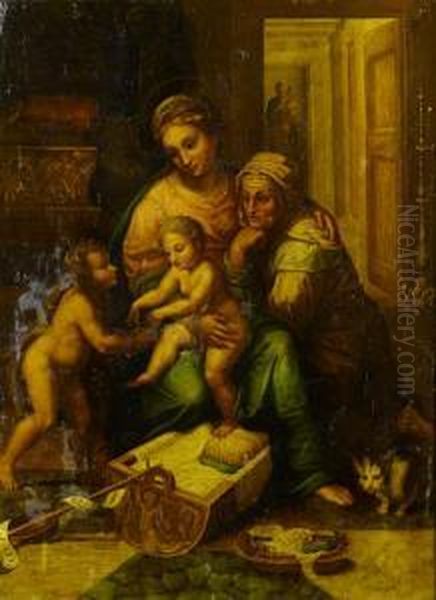

The interior of the Palazzo del Te is as remarkable as its exterior, featuring extensive fresco cycles designed by Giulio and executed with his workshop assistants. These decorations are integral to the building's purpose as a place of courtly pleasure and display, drawing heavily on classical mythology and literature. Two rooms are particularly famous: the Sala di Psiche (Room of Psyche) and the Sala dei Giganti (Room of the Giants).

The Sala di Psiche depicts the mythological story of Cupid and Psyche, based on Apuleius's Metamorphoses. The frescoes are filled with sensual, fleshy figures celebrating the eventual marriage banquet of the protagonists. The style is opulent and dynamic, clearly influenced by both Raphael's mythological scenes and Michelangelo's powerful nudes, yet imbued with Giulio's characteristic energy and richness of detail. It served as a spectacular setting for Gonzaga banquets.

Even more dramatic is the Sala dei Giganti. Here, Giulio created an immersive illusionistic environment depicting the mythological Gigantomachy, the battle between the Olympian gods and the rebellious Giants. Frescoes cover the walls and ceiling seamlessly, showing Jupiter hurling thunderbolts from above while the Giants are crushed by collapsing architecture below. The viewer feels caught in the midst of the cataclysm. The distorted perspectives, exaggerated musculature, and overwhelming sense of chaos make this room a prime example of Mannerist intensity and illusionism. Other rooms feature diverse themes, showcasing Giulio's versatility and erudition.

Giulio's Workshop and Mantuan Projects Beyond the Palazzo

Giulio Romano's position in Mantua extended far beyond the Palazzo del Te. As court architect and artist, he was involved in a wide range of projects for the Gonzaga family and the city. He established a large and efficient workshop, training numerous assistants who helped execute his designs. This workshop practice, learned from Raphael, allowed him to manage multiple large-scale commissions simultaneously. Among his notable assistants who later achieved fame was Francesco Primaticcio, who would play a crucial role in transmitting the Italian Mannerist style to France at the court of Fontainebleau.

Giulio undertook renovations and redesigns for the Mantuan Cathedral (Duomo di Mantova), particularly after a fire. He designed his own house in Mantua (c. 1544), a building that reflects his architectural principles on a smaller scale, featuring a striking facade that plays with classical motifs, similar to his work at the Palazzo del Te. He was also involved in designing temporary structures for festivals, courtly entertainments, and state occasions, showcasing his versatility.

Furthermore, his role sometimes extended to engineering tasks, such as drainage projects and fortifications, demonstrating the broad scope of responsibilities held by a leading court artist-architect in the Renaissance. His pervasive influence reshaped the visual character of Mantua, leaving an indelible mark on the city's architecture and art that is still evident today.

Artistic Style: Mannerism Personified

Giulio Romano's artistic style is central to the definition and understanding of Mannerism. While deeply indebted to Raphael's High Renaissance classicism – characterized by harmony, balance, idealized forms, and clarity – Giulio consciously deviated from these principles to create a style that was more complex, artificial, and emotionally charged. This transition is evident even in the works completed immediately after Raphael's death.

Key characteristics of Giulio's Mannerist style include:

1. Complexity of Composition: Crowded scenes, intricate groupings of figures, and dynamic, often swirling, compositions replaced the stable, pyramidal arrangements favored by Raphael.

2. Elongated and Muscular Figures: While drawing on Michelangelo's powerful nudes, Giulio often elongated proportions and exaggerated musculature for expressive effect. Poses became more contrived and difficult (figura serpentinata).

3. Emotional Intensity: Serene detachment gave way to heightened drama, intense emotions, and sometimes unsettling psychological states. This is particularly evident in the Sala dei Giganti.

4. Artifice and Sophistication: A self-conscious awareness of style, playing with classical rules, employing complex allegories, and aiming for intellectual wit and visual surprise.

5. Rich Detail and Ornamentation: A love for decorative detail, rich textures, and elaborate settings, sometimes at the expense of narrative clarity.

6. Unconventional Color and Light: While sometimes using Raphaelesque palettes, he could also employ sharper contrasts, more acidic colors, and dramatic lighting effects to enhance the mood.

His style contrasted with the more lyrical and elegant Mannerism of artists like Parmigianino or the intense, neurotic spirituality found in Pontormo or Rosso Fiorentino, yet he shared with them a fundamental desire to explore artistic possibilities beyond the established norms of the High Renaissance.

Drawings and Designs for Various Media

Giulio Romano was an exceptionally prolific draftsman. Hundreds of his drawings survive, revealing his creative process and his skill across various techniques, including pen and ink, wash, chalk, and metalpoint. These drawings range from rapid compositional sketches to highly finished presentation drawings (modelli) for paintings, frescoes, and architectural projects. They demonstrate his fertile imagination, his command of human anatomy, and his dynamic sense of movement.

His drawings were not solely preparatory studies for painting and architecture. Reflecting the broad role of a Renaissance court artist, Giulio also produced designs for a wide array of other media. These included designs for tapestries, metalwork (such as plates and ewers), stucco decorations, theatrical sets, and festival decorations. This versatility was highly valued by his patrons.

His designs were often disseminated through prints made by engravers like Marcantonio Raimondi (before the I Modi scandal) and later Giorgio Ghisi. This helped spread his stylistic innovations and motifs beyond Mantua. The sheer volume and quality of his graphic output underscore his relentless energy and the central role drawing played in his artistic practice, serving as the foundation for his diverse creations.

Relationships with Contemporaries: Collaboration and Context

Giulio Romano's career unfolded amidst a constellation of major artistic figures. His relationship with Raphael was foundational, defining his early career and legacy. He worked alongside other members of Raphael's workshop, most notably Gianfrancesco Penni, with whom he initially shared the inheritance of the workshop, though their paths later diverged. His collaboration with the engraver Marcantonio Raimondi was significant, both for disseminating Raphael's designs and for the infamous I Modi project.

His move to Mantua was facilitated by Baldassare Castiglione, highlighting the interconnectedness of artistic and literary circles. His patron, Federico II Gonzaga, provided the crucial support for his most ambitious projects. In Mantua, he would have encountered or been aware of other artists working in Northern Italy, including the Venetian master Titian, who visited the Mantuan court and painted portraits of the Gonzaga family. While their styles differed significantly, Titian's rich colorism may have had some influence on Giulio's later Mantuan works.

Giulio's work stands in contrast to the towering figure of Michelangelo. While both artists explored powerful human forms and dramatic expression, Michelangelo's art was rooted in a profound spiritual and philosophical depth, whereas Giulio's often leaned towards theatricality, sensuality, and decorative richness. He would also have been aware of the developments of early Mannerism in Florence through artists like Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino, and in Parma through Parmigianino. The art historian Giorgio Vasari, in his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, provided the earliest and highly influential biography of Giulio, praising his talent while sometimes criticizing his departure from Raphaelesque grace. Other artists like Benvenuto Cellini also mention him in their writings. His assistant Francesco Primaticcio carried his style to the French court, influencing artists there.

Influence and Legacy: Shaping Mannerism and Beyond

Giulio Romano's impact on the course of 16th-century art was profound and far-reaching. As Raphael's primary heir, he played a crucial role in disseminating the High Renaissance style, albeit transformed through his own Mannerist sensibility. His work in Rome, particularly the completion of Raphael's projects, solidified his reputation and influenced younger artists in the city.

His move to Mantua and the creation of the Palazzo del Te established a major center of Mannerist art and architecture outside the traditional hubs of Rome and Florence. The Palazzo became a model studied by artists and architects for its innovative design and spectacular decorations. His workshop trained numerous artists, spreading his style throughout Northern Italy.

Perhaps most significantly, Giulio's influence extended north of the Alps, primarily through his pupil Francesco Primaticcio. Summoned to the French court by King Francis I, Primaticcio, along with Rosso Fiorentino, became a key figure in the School of Fontainebleau, decorating the royal palace in a style heavily indebted to Giulio's Mantuan Mannerism. This established a sophisticated Mannerist idiom in France that dominated artistic production for decades.

Giulio's fame was such that he is the only Italian Renaissance artist mentioned by name in the works of William Shakespeare. In The Winter's Tale, the statue of Hermione, so lifelike that it seems to come alive, is attributed to "that rare Italian master, Julio Romano," a testament to his reputation for naturalism and artistic skill, even if Shakespeare conflates his painting and architectural fame with sculpture.

Art Historical Evaluation: A Complex Legacy

Art historical assessment of Giulio Romano has evolved over time. For centuries, particularly influenced by Vasari and later classicist critics, he was often viewed primarily as Raphael's talented but less refined successor. His Mannerist tendencies – the complexity, artifice, and sometimes jarring elements – were frequently judged negatively against the perceived perfection and harmony of Raphael's High Renaissance style. He was sometimes criticized for a certain coarseness or lack of subtlety compared to his master.

However, with the reassessment of Mannerism in the 20th century, Giulio's reputation has been significantly rehabilitated. Art historians now recognize him not just as an imitator of Raphael, but as a highly original artist who creatively transformed his inheritance. He is acknowledged as a central figure in the development and definition of Mannerism, praised for his inventiveness, his technical virtuosity, and his ability to integrate painting, architecture, and decoration into unified ensembles.

His work at the Palazzo del Te is now celebrated as a masterpiece of Mannerist design, admired for its wit, sophistication, and dramatic power. His drawings are highly valued for their energy and insight into his creative process. While the comparison with Raphael remains inevitable, Giulio Romano is now understood on his own terms: a versatile, prolific, and highly influential master whose work embodies the dynamic and often contradictory spirit of the 16th century. He was a crucial bridge between the High Renaissance and the subsequent developments of Italian and European art.

Conclusion: An Enduring Influence

Giulio Romano, born Giulio Pippi, remains a towering figure in the landscape of Italian Renaissance art. From his beginnings as Raphael's most gifted pupil to his mature career as the driving artistic force at the Gonzaga court in Mantua, he navigated the transition from High Renaissance ideals to the complexities of Mannerism with extraordinary skill and imagination. As both a painter and architect of the first rank, he created works, most notably the Palazzo del Te, that continue to fascinate and impress with their inventiveness, technical brilliance, and sophisticated play on classical forms. Though sometimes overshadowed by his master, Raphael, or compared to the intense spirituality of Michelangelo, Giulio forged a unique and powerful artistic identity. His influence, spread through his own works, his workshop, and artists like Primaticcio, was instrumental in shaping the course of Mannerism across Europe, leaving a rich and complex legacy that continues to be studied and admired.