Giulio Romano stands as a pivotal figure in the Italian Renaissance, a versatile artist whose talents spanned painting, architecture, and design. Born Giulio Pippi, he rose from being the chief pupil and collaborator of the High Renaissance master Raphael to become a leading force in the development of Mannerism. His career bridged the classical harmony of his teacher with a new, more dynamic and emotionally charged artistic language, leaving an indelible mark on the art of the 16th century, particularly through his extensive work in Mantua.

Early Life and the Shadow of Raphael

The precise origins of Giulio Romano remain somewhat debated among historians. While his death on November 1, 1546, in Mantua is well-documented, his birth year is contested. Some sources point to circa 1499, while others suggest an earlier date, around 1492. He was born in Rome, originally bearing the surname Pippi, later adopting variations like Giulio di Pietro Filippo de' Giannuzzi before becoming universally known as Giulio Romano, signifying his Roman origins.

His artistic journey began under the most auspicious circumstances possible in Renaissance Rome: apprenticeship in the bustling workshop of Raphael Sanzio. Giulio quickly distinguished himself, becoming not just a student but Raphael's most trusted assistant and collaborator. During these formative years, he absorbed the principles of High Renaissance classicism, mastering drawing, composition, and the harmonious integration of figures that characterized Raphael's style.

Giulio's hand is evident in several major projects undertaken by Raphael's workshop. He played a significant role in the execution of frescoes in the Vatican Stanze, particularly in the Stanza dell'Incendio di Borgo. Works like the Fire in the Borgo show evidence of his involvement, likely working from Raphael's designs but already hinting at a more muscular and vigorous treatment of figures compared to his master's typical grace. He also contributed to the decorations of the Villa Farnesina for the wealthy banker Agostino Chigi, another of Raphael's major patrons.

His closeness to Raphael was profound. When the great master died unexpectedly in 1520, Giulio Romano, alongside another key workshop member, Gianfrancesco Penni, was named as Raphael's principal heir. This inheritance included not just drawings and studio materials but also the responsibility of completing the numerous prestigious commissions left unfinished by Raphael's untimely death. This marked a crucial turning point, thrusting Giulio into the forefront of the Roman art scene.

Completing the Master's Vision: Rome After Raphael

The immediate aftermath of Raphael's death saw Giulio Romano and Gianfrancesco Penni jointly managing the workshop and tackling the formidable task of completing outstanding projects. One of the most significant was the Sala di Costantino in the Vatican Palace. While Raphael had conceived the overall decorative scheme and possibly prepared initial designs, the actual execution of the large-scale frescoes, depicting scenes from the life of Emperor Constantine, fell largely to his heirs.

Giulio's dominant role is particularly evident in frescoes like The Battle of the Milvian Bridge (often referred to as The Battle of Constantine). Here, the dense, tumultuous composition, the powerful, almost exaggerated musculature of the figures, and the dramatic intensity mark a departure from Raphael's measured classicism. While fulfilling the commission, Giulio infused the scenes with his own burgeoning Mannerist tendencies, emphasizing energy and force over serene balance.

Another critical work from this period was the completion of Raphael's final altarpiece, the Transfiguration. Raphael had reportedly finished the upper section depicting the transfigured Christ before his death. Giulio is credited with completing the lower, more agitated section showing the apostles attempting to heal a possessed boy. The contrast between the divine calm above and the human turmoil below is stark, and while fulfilling Raphael's likely intent, the execution of the lower part bears the hallmarks of Giulio's more forceful style. This completion itself remains a point of discussion, questioning how much it reflects Raphael's final vision versus Giulio's interpretation.

During these years in Rome, Giulio also undertook independent commissions, establishing his reputation beyond merely being Raphael's successor. He worked for prominent patrons, including Pope Clement VII (Giulio de' Medici), for whom he reportedly designed palace elements, possibly contributing early ideas to projects like the Villa Madama, initially conceived by Raphael. His versatility was already apparent, extending beyond large-scale frescoes to panel paintings and potentially architectural designs.

However, this period also saw criticism emerge. While acknowledging his technical skill, some contemporaries and later critics, like the influential biographer Giorgio Vasari, felt Giulio lacked Raphael's innate grace, subtlety, and perhaps the profound intellectual or spiritual depth that animated his master's greatest works. His figures were sometimes seen as overly robust or even coarse, prioritizing anatomical display and dramatic effect over idealized beauty. This tension between inheritance and innovation would define much of his career.

The Call to Mantua: Service to the Gonzaga

A decisive shift occurred in 1524 when Giulio Romano accepted an invitation from Federico II Gonzaga, the Duke of Mantua. This move was facilitated by Baldassare Castiglione, the diplomat and author of The Book of the Courtier, a close friend of Raphael and an admirer of Giulio's talents. Leaving the competitive environment of Rome, where artists like Michelangelo Buonarroti cast long shadows, Giulio found in Mantua an opportunity to become the dominant artistic force, enjoying the consistent patronage of an ambitious ruler eager to transform his court into a major cultural center.

Federico II Gonzaga granted Giulio extraordinary authority, appointing him prefect of the city's artistic projects and superintendent of streets. This position gave Giulio control not only over ducal commissions but also over urban planning and public works. He essentially became the chief architect and image-maker for the Gonzaga court, a role that allowed his multifaceted talents to flourish unimpeded for the rest of his life.

His arrival in Mantua marked the beginning of the most productive and arguably most significant phase of his career. He established a large and active workshop, attracting numerous assistants and pupils who helped execute his designs and disseminate his style. This workshop became a vital hub for artistic production in Northern Italy, influencing a generation of artists. Mantua provided the canvas upon which Giulio could fully express his artistic vision, moving further from Raphael's shadow and solidifying his position as a leading exponent of Mannerism.

Architectural Dominance: The Palazzo del Tè

Giulio Romano's architectural genius found its most spectacular expression in Mantua, most notably in the design and decoration of the Palazzo del Tè. This suburban villa, built between roughly 1524 and 1534 on the outskirts of Mantua, was conceived as a place of leisure and pleasure (originally stables transformed) for Federico II Gonzaga. It stands as a landmark of Mannerist architecture, a playful, sophisticated, and often deliberately rule-breaking engagement with classical forms.

The exterior of the Palazzo del Tè immediately signals its unconventional nature. Giulio employed classical elements like Doric columns, triglyphs, and metopes, but arranged them in unexpected ways. Rusticated stucco surfaces contrast with smooth finishes. Triglyphs appear to "slip" down in the entablature, keystones seem oversized or dropped in window pediments, and the rhythm of columns and bays is intentionally irregular. These architectural "jokes" or licenze (licenses) subvert the strict rules of classical orders codified by architects like Vitruvius and Bramante, creating a sense of dynamism, surprise, and intellectual wit aimed at a sophisticated courtly audience.

The interior courtyard continues this theme, with its massive, heavily rusticated columns and seemingly "unfinished" or deliberately crude surfaces juxtaposed with more refined elements. The entire structure avoids monumentality in favour of a sprawling, almost theatrical layout designed for entertainment and the display of Gonzaga power and culture.

Beyond the architecture itself, Giulio oversaw the complete interior decoration, designing intricate stucco work and illusionistic frescoes that covered the walls and ceilings of the main state rooms. These decorative schemes, executed with his workshop, are integral to the building's effect and represent the pinnacle of his Mannerist vision. The Palazzo del Tè is not merely a building but a total work of art, a Gesamtkunstwerk, orchestrated by Giulio Romano.

Other significant architectural projects in Mantua included the extensive renovation and rebuilding of the Mantua Cathedral (Duomo di San Pietro) after a fire, where he redesigned the interior. He also worked on the church of San Benedetto Po, a major Benedictine abbey near Mantua, contributing designs for its rebuilding. Furthermore, demonstrating his civic role, he designed his own impressive house in Mantua (now known as the Casa di Giulio Romano), showcasing his architectural ideas on a domestic scale, and even tackled practical urban problems by designing improvements to the city's drainage system to combat flooding.

Frescoes and Paintings: The Mannerist Vision Unleashed

Giulio Romano's work as a painter reached its zenith in the decorative schemes of the Palazzo del Tè. Here, freed from the constraints of purely religious commissions and working for a secular patron eager for novelty, he unleashed his imagination, creating complex mythological narratives filled with energy, sensuality, and illusionistic bravura.

The Sala di Psiche (Room of Psyche) recounts the mythological love story of Cupid and Psyche, based on Apuleius's The Golden Ass. The walls are filled with vibrant, often erotic scenes depicting the trials and tribulations of Psyche and the banquets of the gods. The figures are muscular, dynamic, and arranged in complex, overlapping groups. The overall effect is one of opulent, sensual celebration, perfectly suited to the villa's function as a place of pleasure.

Even more famous is the Sala dei Giganti (Room of the Giants). This staggering room is perhaps Giulio's most radical creation. Covering the walls and ceiling entirely, the fresco depicts the mythological Gigantomachy – the Olympian gods casting down the rebellious giants who sought to storm Mount Olympus. Giulio creates a complete illusionistic environment; the architecture of the room seems to dissolve as painted clouds, rocks, and colossal figures tumble down around the viewer. Jupiter hurls thunderbolts from the ceiling oculus, while the giants are crushed by collapsing architecture below. The perspective is deliberately distorted and unstable, immersing the viewer directly in the chaotic, overwhelming scene. It is a tour-de-force of illusionism and dramatic power, a prime example of Mannerist theatricality and emotional intensity.

Beyond the Palazzo del Tè, Giulio continued to produce panel paintings, although large-scale fresco cycles and architectural design dominated his Mantuan years. Works like the Madonna and Child with Saints (various versions exist, including the Madonna della Gatta) show his adaptation of Raphaelesque compositions but with a cooler palette, elongated figures, and a more complex interplay of gazes and gestures typical of Mannerism. The Stoning of St. Stephen, created for the church of Santo Stefano in Genoa, is another powerful example of his dramatic narrative style, filled with dynamic action and intense emotion.

His drawings were also highly influential. Often characterized by strong outlines and energetic hatching, they served as models for his workshop and were disseminated through prints made by engravers like Marcantonio Raimondi. This included the controversial series I Modi (The Positions), explicit erotic prints based on Giulio's designs accompanied by sonnets by Pietro Aretino, which caused a scandal but also attest to the less inhibited aspects of Renaissance court culture.

Artistic Style: Defining Mannerism

Giulio Romano's art is central to the definition and understanding of Mannerism, the complex artistic style that emerged in Italy around the 1520s, largely succeeding the High Renaissance. Mannerism is often characterized by its artificiality, elegance, and intellectual sophistication, moving away from the naturalism and harmonious balance of artists like Raphael and Leonardo da Vinci.

Giulio's style embodies many key Mannerist traits. He embraced complexity in composition, often filling his canvases and frescoes with numerous figures in intricate, sometimes contorted poses. There is a deliberate emphasis on figura serpentinata – the twisting, serpentine pose – which imbues figures with grace and dynamism but can also appear artificial.

He took liberties with classical proportion and anatomy, elongating limbs, exaggerating musculature, and creating figures that prioritize elegance or power over strict naturalism. This is evident in both his paintings and his architectural designs, where classical rules are knowingly bent or broken for expressive effect. His use of color could be vibrant and decorative, as in the Sala di Psiche, but also sometimes cooler and more artificial than the rich palettes of the High Renaissance or contemporary Venetians like Titian.

A strong sense of drama and emotional intensity pervades his work, particularly in narrative scenes like the Battle of the Milvian Bridge or the Fall of the Giants. He favoured dynamic movement, theatrical gestures, and charged psychological interactions between figures. This contrasts with the serene composure often found in Raphael's work.

His deep knowledge of classical antiquity, absorbed during his Roman years, is evident everywhere, but he treated ancient motifs with a new freedom. Mythological subjects allowed for explorations of sensuality, violence, and complex allegory that appealed to the sophisticated tastes of his courtly patrons. His architecture, while using the classical vocabulary, does so with wit, irony, and a deliberate display of artistic license.

While influenced by Raphael's compositional clarity and Michelangelo's powerful figural style, Giulio forged these influences into a distinct personal idiom. His work is less about idealized beauty and harmonious order, and more focused on invention, technical virtuosity, emotional impact, and a certain stylishness or maniera.

Relationships with Contemporaries: Collaboration and Competition

Giulio Romano operated within a rich network of artists, patrons, and intellectuals. His most defining relationship was, of course, with Raphael, his master and mentor. The complexities of inheriting Raphael's legacy – both the opportunities and the burdens of comparison – shaped his early independent career. His collaboration with Gianfrancesco Penni was crucial in the years immediately following Raphael's death, though Giulio gradually emerged as the more dominant artistic personality.

In Mantua, his primary relationship was with his patron, Federico II Gonzaga, who provided unwavering support and artistic freedom. He also interacted with other figures at the Mantuan court, including the aforementioned Baldassare Castiglione.

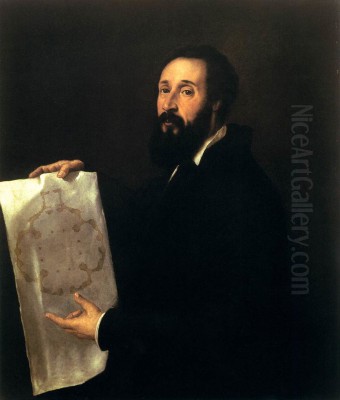

His relationship with other major artists of the time involved both connection and rivalry. Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), the leading figure of the Venetian school, was a contemporary. Evidence suggests they knew each other; Titian painted a portrait of Giulio Romano (now lost, but known through copies and descriptions). Both artists worked for Federico II Gonzaga, with Titian providing portraits and mythological paintings for the Duke, sometimes destined for the same environments Giulio was decorating. While their styles differed significantly – Giulio rooted in Roman drawing and composition, Titian in Venetian color and brushwork – they represented the two dominant poles of North Italian art, likely engaging in a form of professional competition while maintaining some level of mutual respect.

Giulio was certainly aware of the towering figure of Michelangelo, whose work in Rome, particularly the Sistine Chapel ceiling, profoundly impacted all artists of the period. Giulio's emphasis on muscular anatomy and powerful figures owes a debt to Michelangelo, although Giulio's interpretations often lack Michelangelo's deep pathos and spiritual intensity, leaning more towards physical energy and decorative effect.

He also interacted with writers and intellectuals like Pietro Aretino, notorious for his sharp wit and sometimes scandalous writings, who provided the verses for the I Modi prints based on Giulio's drawings. The engraver Marcantonio Raimondi played a crucial role in disseminating Giulio's designs (and those of Raphael) throughout Europe via prints, significantly contributing to his fame and influence.

His workshop trained and influenced numerous artists. One of the most important was Francesco Primaticcio, who assisted Giulio in Mantua before being summoned to France by King Francis I. Primaticcio played a key role in establishing the Mannerist style at the French court, particularly through his work at the Palace of Fontainebleau, directly transmitting Giulio's influence abroad. Other contemporaries whose work provides context include Andrea del Sarto in Florence, Correggio in Parma (known for his own illusionistic ceilings), and Sebastiano del Piombo, a rival of Raphael in Rome who blended Roman and Venetian elements. Giorgio Vasari, whose Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects is a foundational text of art history, knew Giulio and wrote extensively, if sometimes critically, about his life and work. Even figures like Benvenuto Cellini, the famed sculptor and goldsmith, moved in the same circles and faced similar challenges of patronage and artistic rivalry.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Giulio Romano's impact on the art of the 16th century was substantial. As Raphael's primary heir, he ensured the continuation and adaptation of the Raphaelesque tradition, albeit transformed through his own Mannerist sensibility. His work in Rome, particularly the completion of Raphael's projects, set a standard for large-scale decorative painting.

His move to Mantua proved decisive not only for his own career but also for the dissemination of the Mannerist style in Northern Italy and beyond. The Palazzo del Tè became a pilgrimage site for artists and connoisseurs, a stunning demonstration of the new artistic language. Its integration of architecture, stucco, and fresco, and its playful subversion of classical rules, profoundly influenced subsequent palace and villa design.

Through his active workshop and the circulation of prints after his designs, Giulio's style reached a wide audience across Europe. Artists like Primaticcio carried his influence directly to France, contributing significantly to the development of the School of Fontainebleau. His architectural ideas resonated with later architects who explored the expressive potential of breaking classical conventions.

While Vasari praised his facility and invention, later critics, particularly during the Baroque and Neoclassical periods, sometimes viewed his work less favourably, criticizing its perceived lack of naturalism, its occasional coarseness, or its departure from the perceived purity of High Renaissance ideals. His reputation fluctuated over the centuries.

However, modern art history recognizes Giulio Romano as a major innovator. He is seen as a key figure in the transition from High Renaissance to Mannerism, an artist whose work embodies the complexity, sophistication, and expressive power of the new style. His ability to synthesize influences from Raphael and Michelangelo into a unique and dynamic personal language, and his mastery across multiple artistic disciplines, secure his place as one of the most important and versatile artists of his time.

Controversies and Unanswered Questions

Despite his fame, aspects of Giulio Romano's life and work remain subjects of debate and speculation. The uncertainty surrounding his exact birth year (1492 vs. 1499) is a persistent minor puzzle.

More significant are the questions surrounding his completion of Raphael's works. The Transfiguration remains a focal point: how much of the lower section reflects Raphael's final intentions versus Giulio's own interpretation? Did Giulio fully grasp the spiritual and intellectual depth of his master, or did his focus on dynamism and anatomical power represent a fundamental shift, perhaps even a misunderstanding, of Raphael's ideals? Some critics argue that Giulio's translation of Raphaelesque forms into a more muscular, forceful idiom contributed to a decline in classical grace within the Roman school.

There are legends surrounding unrealized projects, such as the purported design for a magnificent door for Milan Cathedral that was never executed – tantalizing hints of "what might have been." The question of whether Giulio himself practiced sculpture remains murky; while primarily known as a painter and architect, occasional references might confuse him with other contemporary artists named Romano, like the sculptor Giovanni Romano.

His artistic style itself has generated controversy. While praised for its invention and energy, it has also been criticized, particularly in painting, for sometimes appearing monochromatic, lacking fine detail, or prioritizing effect over substance. The interpretation of his masterpiece, the Palazzo del Tè, also varies: is it a sophisticated Mannerist playground, a romanticized vision of antiquity, or a display of ducal power bordering on the excessive?

These ambiguities and debates enrich the study of Giulio Romano. They highlight the complexities of artistic inheritance, the challenges of defining stylistic evolution, and the varied ways in which an artist's work can be interpreted by contemporaries and posterity.

Conclusion: A Bridge Between Worlds

Giulio Romano died in Mantua in 1546, reportedly while considering a prestigious offer to become the architect of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome, succeeding Antonio da Sangallo the Younger – a testament to his enduring reputation. His career trajectory was remarkable: from the star pupil of the quintessential High Renaissance master to a leading architect of Mannerist innovation.

He successfully navigated the immense pressure of succeeding Raphael, forging his own distinct artistic identity. While perhaps lacking the sublime grace of his teacher, he brought a new energy, complexity, and psychological intensity to Italian art. His work in Mantua, particularly the Palazzo del Tè, remains a breathtaking monument to his genius and the sophisticated culture of the Gonzaga court.

As both painter and architect, Giulio Romano was a crucial bridge figure, absorbing the lessons of the High Renaissance and transforming them into the dynamic, often unsettling, but always inventive language of Mannerism. His influence extended far beyond Italy, shaping the course of European art in the 16th century. He remains a fascinating and essential figure for understanding the artistic shifts and cultural richness of the later Italian Renaissance.