Hashiguchi Goyō stands as a colossus in the world of early 20th-century Japanese art, particularly within the Shin-hanga (New Prints) movement. Though his printmaking career was tragically brief, spanning a mere six years before his untimely death, the handful of exquisite woodblock prints he produced cemented his reputation as one of the finest artists of his generation. Revered for his sensitive and elegant portrayals of women, he earned the moniker "the Utamaro of the Taishō period," a testament to his skill in capturing feminine grace, echoing the mastery of the great Edo-period ukiyo-e artist Kitagawa Utamaro. Goyō’s work is a delicate fusion of traditional Japanese aesthetics and subtle Western influences, resulting in images of timeless allure and technical perfection.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born Hashiguchi Kiyoshi on December 21, 1880, in Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan, the artist later adopted the art name Goyō. His father, Hashiguchi Kanemizu, was a samurai with a passion for painting in the traditional Shijō style and an amateur artist in the Kanō school tradition. This artistic environment undoubtedly nurtured young Goyō's inclinations. Under his father's tutelage, he received his initial instruction in Kanō school painting. However, recognizing the shifting artistic tides and perhaps his son's unique talents, his father advised him to explore Western-style painting (Yōga) when he was just ten years old.

In 1899, Goyō moved to Kyoto to further his artistic studies. There, he is said to have briefly studied under the Nihonga painter Takeuchi Seihō, though his primary focus soon shifted. He then relocated to Tokyo, the vibrant heart of Japan's rapidly modernizing art world. He enrolled in the prestigious Tokyo School of Fine Arts (Tokyo Bijutsu Gakkō, now Tokyo University of the Arts), where he dedicated himself to mastering Western oil painting. He was a diligent student, graduating at the top of his class in 1905. One of his influential teachers at the school was Kuroda Seiki, a leading figure in the Yōga movement who had studied in France and championed a more Impressionistic approach to Western painting in Japan.

The Journey Towards Printmaking

Despite his academic success in oil painting, Goyō's early career in this medium was met with mixed critical reception. He participated in the inaugural Bunten exhibition (the Ministry of Education's annual art exhibition) in 1907, where his oil painting received a second-prize commendation. However, he reportedly felt that oil painting was not his true calling, perhaps sensing a disconnect between the medium and his innate artistic sensibilities. His interest began to gravitate towards the rich heritage of Japanese ukiyo-e.

A significant turning point came in 1911. Goyō designed a striking ukiyo-e style poster titled Mitsukoshi gofukuten (Mitsukoshi Kimono Shop) for the prominent Mitsukoshi department store. This poster, depicting a modern Japanese woman, won first prize in a competition held by the store and garnered him considerable acclaim, along with a substantial prize of 1,000 yen. This success seems to have solidified his interest in the ukiyo-e tradition and its potential for contemporary expression. He began to immerse himself in the study of classic ukiyo-e masters like Suzuki Harunobu, Torii Kiyonaga, and especially Kitagawa Utamaro, whose depictions of women deeply resonated with him. He also researched the technical aspects of woodblock printing, a craft that had seen a decline in artistic quality with the advent of modern printing technologies.

The Genesis of a Shin-hanga Master

The year 1915 marked Hashiguchi Goyō's formal entry into the world of Shin-hanga printmaking. He was approached by Watanabe Shōzaburō, a visionary publisher who was the principal driving force behind the Shin-hanga movement. Watanabe aimed to revitalize traditional ukiyo-e by collaborating with contemporary artists to produce high-quality woodblock prints that appealed to both Japanese and Western tastes. He recognized Goyō's exceptional talent for design and his deep understanding of ukiyo-e aesthetics.

Their first collaboration was the print Yuami . This iconic work, depicting a partially nude woman stepping from a traditional wooden bath, her skin subtly rendered and her pose exuding a quiet intimacy, was an immediate success. It perfectly encapsulated the Shin-hanga ideal: a modern sensibility combined with traditional subject matter and exquisite craftsmanship. The print showcased Goyō's meticulous attention to detail, from the delicate rendering of the woman's hair to the subtle gradations of color (bokashi) in the background.

Despite the success of Yuami, Goyō's relationship with Watanabe was not without its complexities. Goyō was a perfectionist, deeply involved in every stage of the printmaking process, from the initial design to the carving of the blocks and the final printing. He found Watanabe's commercial approach and desire for greater output at odds with his own painstaking methods and uncompromising standards. After Yuami, Goyō chose to take full control of his print production, becoming his own publisher, carver, and printer for subsequent works, a highly unusual and demanding path for a Shin-hanga artist. This decision, while ensuring the utmost quality, also limited his output.

Artistic Style, Themes, and Meticulous Craftsmanship

Hashiguchi Goyō's artistic style is characterized by a harmonious blend of traditional Japanese aesthetics and a subtle, refined modernism influenced by his Western art training. His primary subjects were bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women), a genre central to ukiyo-e. However, Goyō's women were not mere idealized figures; they possessed a distinct individuality and a quiet, introspective quality that resonated with the changing social landscape of Taishō-era Japan (1912-1926). His women often appear self-possessed, engaged in everyday activities like combing their hair, applying makeup, or relaxing in a hot spring inn.

His compositions are marked by their elegance, balanced design, and exquisite line work. He had an exceptional ability to capture the textures of fabric, the softness of skin, and the intricate details of hairstyles and accessories. His use of color was subtle yet rich, often employing delicate pastels and sophisticated harmonies. A distinctive feature in many of his prints is the use of mica (kirazuri) in the background, which lends a shimmering, luxurious quality to the image, a technique revived from classic ukiyo-e.

Goyō's perfectionism was legendary. He was intimately involved in every aspect of the printmaking process. He would create detailed preparatory sketches and meticulously oversee the carving of the woodblocks by skilled artisans like Takano Shichinosuke and Maeda Kentarō, and the printing by printers such as Somekawa Kanzō. He insisted on the highest quality materials, including fine cherry wood for the blocks and expensive hōsho paper. This unwavering commitment to quality meant that his editions were often very small, sometimes fewer than 80 impressions, and each print was a testament to his artistic vision. This hands-on approach distinguished him from many other Shin-hanga artists who relied more heavily on the publisher's workshop system.

Masterpieces of Fleeting Beauty

In his short printmaking career, Hashiguchi Goyō produced only fourteen completed woodblock prints (thirteen supervised by him before his death, and one completed posthumously based on his designs). Each is considered a masterpiece of the Shin-hanga movement.

_Yuami_ (Woman in a Bath, 1915): As mentioned, his debut print with Watanabe, setting a high standard for modern bijin-ga. The depiction of the woman's damp skin and the steam-filled atmosphere is particularly masterful.

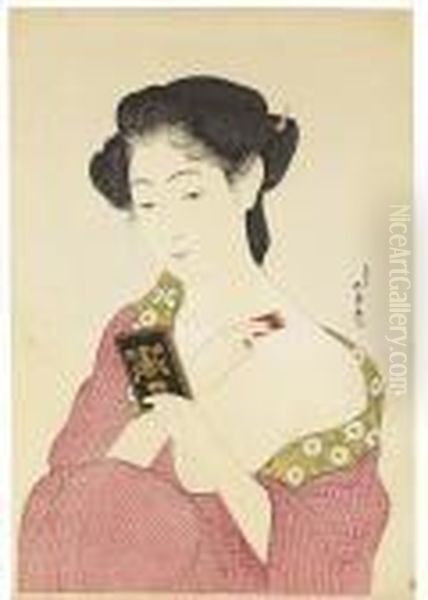

_Keshō no Onna_ (Woman Applying Makeup, 1918): This print shows a woman in a patterned kimono, intently applying lipstick while looking into a hand mirror. The rich colors of her robe and the delicate rendering of her face and hands are exemplary. The mica background adds a touch of opulence.

_Kamisuki_ (Woman Combing Her Hair, 1920): Perhaps his most famous work, this print features a woman with her back to the viewer, her long black hair cascading down as she combs it. The graceful lines of her body, the intricate pattern of her under-robe, and the serene atmosphere make this an iconic image of Japanese beauty. The subtle use of embossing (karazuri) on the comb and parts of the robe adds tactile interest.

_Obon o Motsu Onna_ (Woman Holding a Tray, 1920): This print depicts a woman in a summer yukata carrying a lacquer tray. The simplicity of the composition and the gentle expression of the woman convey a sense of quiet domesticity.

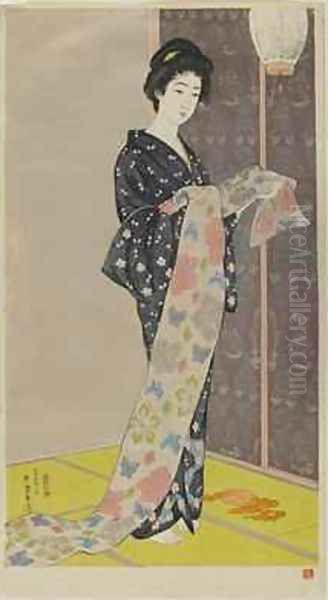

_Onsen Yado_ (Hot Spring Inn, 1921): This was the last print Goyō supervised before his death. It shows a young woman in a yukata standing on the veranda of a hot spring inn, looking out at an unseen view. The mood is one of peaceful contemplation, and the print is noted for its beautiful depiction of the fabric and the subtle evening light.

_Natsu Ishō no Musume_ (Young Woman in Summer Clothing, 1920): A portrait of a woman in a light, patterned summer kimono, holding a fan. Her direct gaze and relaxed posture give her a modern, approachable feel.

_Tenugui Motsu Onna_ (Woman Holding a Towel, 1920): This print captures a woman, possibly after a bath, holding a small towel. The focus is on her serene expression and the delicate rendering of her skin and hair.

Beyond his celebrated bijin-ga, Goyō also produced a few exquisite landscapes and nature studies, though these are less numerous.

_Yabakei no Ame_ (Rain at Yabakei, 1918): A beautifully atmospheric landscape depicting rain falling over the Yabakei valley. The soft, misty quality is reminiscent of traditional ink painting, yet it possesses a modern graphic sensibility.

_Ahiru_ (Ducks, 1919): A charming depiction of two ducks, showcasing his versatility and skill in capturing nature with the same finesse he applied to his human subjects.

Contemporaries and the Shin-hanga Milieu

Hashiguchi Goyō operated within a vibrant artistic community, even if his independent approach to production set him somewhat apart. The Shin-hanga movement itself was a collective endeavor, largely orchestrated by publishers like Watanabe Shōzaburō, who also worked with other prominent artists.

Watanabe Shōzaburō was, of course, central. His stable of artists included Kawase Hasui, who became renowned for his evocative landscape prints, capturing the beauty of Japan's countryside and urban scenes with a nostalgic and poetic sensibility. Another key artist working with Watanabe was Itō Shinsui, who, like Goyō, specialized in bijin-ga. Shinsui's women often possessed a more overtly sensual or melancholic beauty compared to Goyō's introspective figures. Shinsui and Goyō are often considered the two leading masters of Shin-hanga bijin-ga, though their styles differed.

Hiroshi Yoshida was another major figure in Shin-hanga, known for his stunning and technically complex landscape prints. Unlike most Shin-hanga artists, Yoshida eventually established his own studio and supervised his own printing, much like Goyō, allowing him greater artistic control. His works often featured scenes from his extensive travels in Japan and abroad.

Other notable Shin-hanga artists active during or shortly after Goyō's time include:

Yamakawa Shūhō: A student of Itō Shinsui, also known for his elegant bijin-ga.

Torii Kotondo: Another artist famed for his sensual and psychologically nuanced depictions of women, often with a striking modern flair.

Ohara Koson (Shōson): Specialized in kachō-ga (bird-and-flower prints), producing incredibly detailed and lifelike images of nature.

Natori Shunsen: Famous for his powerful and expressive portraits of Kabuki actors (yakusha-e).

Kasumatsu Shirō: Created a wide range of landscapes and scenes of modern Japanese life.

Tsuchiya Koitsu: Known for his romantic and atmospheric landscape prints, often published by Doi Sadaichi.

Kobayakawa Kiyoshi: Another artist who produced striking bijin-ga, sometimes with a more daring or modern feel.

Hirano Hakuhō: Produced a very small number of exquisite bijin-ga in the 1930s, showing a clear influence from artists like Goyō.

Ishiwata Kōitsu: A landscape artist whose work, like Hasui's, captured the serene beauty of Japan.

While Goyō's direct collaborative interactions might have been limited after he began self-publishing, he was undoubtedly aware of and influenced by the broader artistic currents of his time. His decision to focus on such high quality, even at the expense of quantity, set a benchmark within the Shin-hanga movement.

A Brief but Brilliant Career and Posthumous Legacy

Tragically, Hashiguchi Goyō's flourishing career was cut short. He contracted meningitis and, despite efforts to save him, passed away on February 24, 1921, at the young age of 40 (41 by Japanese counting). It is said that even on his deathbed, he was giving instructions for the printing of his final work, Onsen Yado.

His death was a significant loss to the Japanese art world. He left behind a small but exceptionally refined body of work. After his passing, his elder brother, Hashiguchi Yasuo, and his nephew, Hashiguchi Gorō, undertook the task of printing from some of his remaining designs to honor his legacy. These posthumous prints, while still beautiful, are generally distinguished by collectors from the lifetime editions that Goyō himself supervised.

A further tragedy struck when many of Goyō's original woodblocks and some existing prints were destroyed in the Great Kantō Earthquake of 1923. This event further increased the rarity and value of his surviving works. Despite the limited number of original designs, his prints were so highly regarded that later publishers, such as Yūyūdō and Tanseisha, obtained permission from his heirs to create posthumous editions from newly carved blocks based on his original designs or from the few remaining original blocks. These later editions, while not carrying the same cachet as lifetime impressions, helped to keep his art accessible to a wider audience.

Goyō's Enduring Influence and Place in Art History

Hashiguchi Goyō's influence on subsequent generations of artists and his standing in art history are undeniable. He is consistently ranked among the foremost masters of the Shin-hanga movement and, indeed, of 20th-century Japanese printmaking. His work demonstrated that the traditional ukiyo-e format could be revitalized and imbued with a modern sensibility without sacrificing its inherent beauty or technical sophistication.

His meticulous approach to craftsmanship and his unwavering pursuit of artistic perfection set a high standard. While other Shin-hanga artists produced far more extensive oeuvres, Goyō's concentrated body of work is prized for its consistent quality and refined aesthetic. His bijin-ga are particularly celebrated for their psychological depth and their portrayal of women who are both elegant and relatable. He managed to capture a sense of intimacy and introspection that was unique in the genre.

Collectors worldwide highly covet Goyō's lifetime prints, which command significant prices at auction. His work is featured in major museum collections globally, including the Tokyo National Museum, the Art Institute of Chicago, the British Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Exhibitions of his art continue to draw admiration, and scholarly research further illuminates his contributions.

In conclusion, Hashiguchi Goyō, despite his short life, left an indelible mark on Japanese art. He was a bridge between the rich legacy of ukiyo-e and the modern artistic expressions of the 20th century. His dedication to beauty, his technical mastery, and his sensitive portrayal of the feminine ideal ensure his enduring legacy as a true master, whose exquisite visions of Japanese women continue to captivate and inspire.