Kitagawa Utamaro stands as one of the towering figures of Japanese ukiyo-e, the art of the "floating world." Active during the late Edo period, his name became synonymous with bijin-ga, pictures of beautiful women. While the intimate details of his life remain shrouded in some mystery, his prolific output and revolutionary approach to depicting the female form left an indelible mark not only on Japanese art but also on the Western world, significantly shaping the course of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism through the phenomenon of Japonisme. His work offers a captivating window into the culture, aesthetics, and social dynamics of late 18th and early 19th century Japan.

Utamaro's genius lay in his ability to move beyond mere representation, capturing the subtle nuances of personality, emotion, and the intimate moments of women's lives, from the celebrated courtesans of the Yoshiwara pleasure district to ordinary townswomen. He innovated technically and compositionally, creating images of enduring beauty and psychological depth that continue to fascinate viewers today. This exploration delves into the life, art, and lasting influence of this enigmatic master.

Enigmatic Origins and Early Training

The precise details surrounding Kitagawa Utamaro's birth remain uncertain, a common ambiguity for artists of his era whose origins were often humble or deliberately obscured. Born around 1753, potential birthplaces mentioned by various sources include Edo (modern Tokyo), Kyoto, Osaka, Kawagoe, or even Ashikaga, though none are definitively proven. Some traditions even suggest a connection to the Gion district of Edo, but concrete evidence is lacking. His original name is also unknown; "Utamaro" was an art name (gō) adopted later in his career.

![The Complete Set Of 8

Double-page Illustrations From The 1789 Albumshiohi No Tsuto (gifts From

The Ebb Tide) Each With Kyoka Poems,first Printing, Comprising Number

One Shellgathering At Low Tide[shiohi Gari], Number Two Sudare-gai,

Number Three B by Kitagawa Utamaro](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/2881607/m/kitagawa-utamaro-the-complete-set-of-8-doublepage-illustrations-from-the-1789-albumshiohi-no-tsuto-gifts-from-the-ebb-tide-each-with-kyoka-poemsfirst-printing-comprising-number-one-shellgathering-at-low-tideshiohi-gari-number-two-sudaregai-number-three-b-f34bf1d2.jpg)

What is more certain is his artistic tutelage. Utamaro studied under the painter Toriyama Sekien (1712-1788). Sekien was an artist of the Kanō school lineage but is perhaps best known today for his illustrated compendiums of Japanese folklore creatures, the yōkai. This apprenticeship would have provided Utamaro with a solid foundation in traditional painting techniques and composition, even though he would ultimately diverge significantly from the Kanō school's classical style. Sekien's interest in diverse subjects, including the supernatural, might also have subtly encouraged Utamaro's later exploration of varied themes beyond conventional portraiture.

During his formative years, Utamaro would have been exposed to the works of established ukiyo-e masters. The influence of artists like Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815) is particularly noticeable in Utamaro's earlier works. Kiyonaga was renowned for his elegant, full-length depictions of graceful women, often set in panoramic compositions. Utamaro absorbed Kiyonaga's sense of elegance and refined line, but he would soon develop his own distinct artistic voice, moving towards more intimate and psychologically focused portrayals.

The Golden Age: Collaboration and Innovation

Utamaro's career truly flourished from the late 1780s through the 1790s, a period often considered his "golden age." A crucial factor in this success was his close association with the influential publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō (1750-1797). Tsutaya was a discerning and ambitious figure in the Edo publishing world, known for recognizing and nurturing talent. He published works by many leading writers and artists of the day, including the satirical writer Santō Kyōden and, for a brief, intense period, the enigmatic actor-portraitist Tōshūsai Sharaku.

Tsutaya became Utamaro's primary publisher and patron, providing him with commissions and artistic freedom. Their relationship was reportedly close; Tsutaya is said to have frequently accompanied Utamaro on visits to the Yoshiwara pleasure quarters, Edo's licensed red-light district. These excursions were not merely for leisure but served as vital research, allowing Utamaro to observe firsthand the manners, fashions, and intimate lives of the courtesans who would become central subjects in his art. This collaboration provided Utamaro with the platform and resources needed to experiment and refine his unique vision.

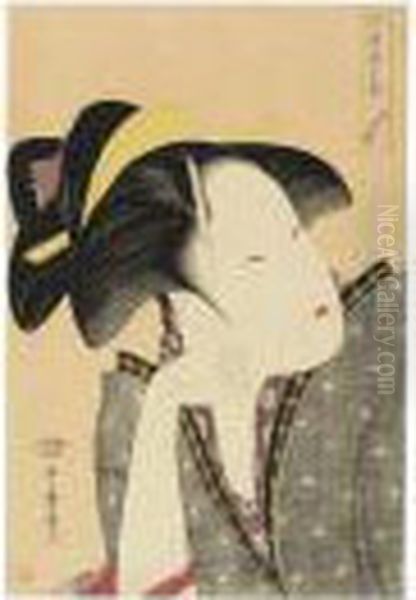

It was during this period, under Tsutaya's patronage, that Utamaro increasingly specialized in bijin-ga. He began to move away from the full-length figures favored by Kiyonaga and pioneered the ōkubi-e format – large-head or bust portraits. This compositional innovation was revolutionary. By focusing closely on the face and upper torso, Utamaro could lavish attention on subtle facial expressions, intricate hairstyles, delicate fabric patterns, and the rendering of skin, bringing an unprecedented level of intimacy and psychological presence to his subjects.

Artistic Style: Capturing Inner Worlds

Kitagawa Utamaro's artistic style is characterized by its elegance, sensitivity, and technical brilliance. His primary focus was the female form, but his approach differed significantly from many predecessors who often depicted women as idealized types. Utamaro sought to capture individuality and inner emotion, presenting his subjects with a sense of realism and psychological depth previously unseen in bijin-ga.

His line work is exceptionally fine and fluid, defining contours with grace and precision. He masterfully conveyed the softness of skin, the weight and texture of fabric, and the intricate details of hairstyles and ornaments. This linear elegance was combined with a sophisticated use of color. Utamaro worked extensively with nishiki-e ("brocade pictures"), the multi-block color printing technique perfected by earlier artists like Suzuki Harunobu (c. 1725-1770). Utamaro, however, expanded the palette and employed subtle color gradations and juxtapositions to enhance the mood and realism of his prints.

A distinctive feature of many of Utamaro's finest prints is the use of mica (kira-zuri) in the background. Pulverized mica powder was dusted onto the wet ink of the background areas, creating a shimmering, iridescent effect that added a sense of luxury and highlighted the figure. He also experimented with other techniques, such as embossing (creating raised areas without ink) to suggest fabric patterns or contours, further adding to the tactile quality of his prints.

The ōkubi-e format allowed Utamaro to explore the nuances of expression. His women are rarely passive beauties; they are shown thinking, feeling, reacting. He captured fleeting moments – a woman wiping sweat from her brow, adjusting a hairpin, reading a letter, lost in thought. This focus on transient moments and subtle gestures imbued his work with a sense of intimacy and voyeurism, as if the viewer has stumbled upon a private scene. He depicted not just the high-ranking courtesans but also geishas, teahouse waitresses, and ordinary mothers, revealing the spectrum of female life in Edo.

Diverse Themes: Beyond the Beauties

While Utamaro is most celebrated for his bijin-ga, his artistic interests were broader. He produced a significant body of work exploring the natural world, particularly in illustrated books (ehon). His Ehon Mushi Erami (Picture Book of Selected Insects, 1788) and Shiohi no Tsuto (Gifts of the Ebb Tide, c. 1789-90), featuring exquisite studies of insects and seashells respectively, demonstrate his keen powers of observation and delicate rendering skills applied to nature. These works are masterpieces of naturalist illustration, combining scientific accuracy with artistic sensibility.

Utamaro was also a master of shunga, or erotic art. These "spring pictures" were a popular and accepted genre within ukiyo-e, though subject to occasional censorship. Utamaro approached shunga with the same artistic refinement and psychological insight he brought to his bijin-ga. His shunga often focus on the emotional connection between lovers, depicted with elegance and sensuality rather than crude explicitness. His most famous shunga album, Utamakura (Poem of the Pillow, 1788), is considered one of the pinnacles of the genre, showcasing his mastery of composition and emotional expression even within the confines of erotic subject matter.

He also created illustrations for kyōka poetry anthologies (a form of humorous, satirical verse) and occasionally depicted historical or legendary scenes. This thematic diversity underscores Utamaro's versatility and his engagement with the wider cultural milieu of Edo. However, it was his depictions of contemporary women that cemented his fame and legacy.

Masterpieces and Major Series

Throughout his prolific career, estimated to encompass over 2,000 individual print designs and dozens of illustrated books, Utamaro produced numerous works now considered icons of ukiyo-e. Several series stand out for their innovation and artistic quality.

The series Fujin Sōgaku Jittai (Ten Studies in Female Physiognomy, c. 1792-93) exemplifies his focus on revealing personality through facial features and expression. Each print isolates a different "type," such as the "wanton" type or the "flirtatious" type, using the ōkubi-e format to scrutinize their faces.

Another important series is Kasen Koi no Bu (Anthology of Poems: The Love Section, c. 1793-94), which pairs portraits of women experiencing different facets of love with relevant kyōka poems. The prints explore themes like hesitant love, deep affection, and heartbreak, showcasing Utamaro's ability to translate complex emotions into visual form. The famous print Fukaku Shinobu Koi (Deeply Hidden Love) from this series is a prime example of his subtle emotional portrayal.

Tōji San Bijin (Three Beauties of the Present Day, c. 1793) is one of his most famous single-sheet prints, depicting three celebrated beauties of the era: the geishas Tomimoto Toyohina and Naniwaya Kita, and the teahouse waitress Takashima Hisa. Grouped together in a skillful triangular composition against a shimmering mica background, the print captures their distinct charms and solidifies their status as contemporary icons.

Other notable series include Meisho Fukei Bijin Juniso (Twelve Physionomies of Women Compared with Famous Places), Seirō Jūnitoki Tsuzuki (Twelve Hours in the Yoshiwara), and Kyōkun Oya no Mekane (Parental Advice, depicting mothers and children). His nature studies, like the aforementioned Ehon Mushi Erami and Shiohi no Tsuto, are also considered masterpieces in their own right. The sheer volume and consistent quality of his output during the 1790s are remarkable.

Contemporaries, Rivals, and Pupils

Utamaro worked within a vibrant and competitive artistic environment in Edo. He was keenly aware of his contemporaries and often seemed to respond to their work in his own. His early career shows the influence of Torii Kiyonaga, whose elegant depictions of women set a high standard. As Utamaro developed his own style, particularly the ōkubi-e, he arguably surpassed Kiyonaga in terms of psychological depth and intimacy.

Another significant contemporary specializing in bijin-ga was Chōbunsai Eishi (1756-1829). Eishi, originally a samurai who studied Kanō painting, turned to ukiyo-e and focused on depicting slender, elegant courtesans, often in refined settings. While both artists excelled at bijin-ga, Eishi's figures tend to be more idealized and less emotionally revealing than Utamaro's, representing a different aesthetic sensibility within the genre. There was likely a degree of rivalry between them as they catered to similar markets.

The brief but brilliant career of Tōshūsai Sharaku (active 1794-95) overlapped with Utamaro's peak. Sharaku, also published by Tsutaya Jūzaburō, focused almost exclusively on dramatic portraits of Kabuki actors, employing startling realism and psychological intensity. While their subject matter differed, both artists pushed the boundaries of portraiture within ukiyo-e during the same period.

Utamaro also had pupils who carried on his style, sometimes leading to confusion in attribution. The most notable was Koide Shunshō, who later took the name Kitagawa Utamaro II (?-c. 1831) after his master's death. While Utamaro II continued to produce bijin-ga in his master's manner, his work generally lacks the subtlety and emotional depth of the original Utamaro. Other artists like Kikumaro (Chikarō) also followed his style.

Conflict with Authority and Later Years

Despite his immense popularity, Utamaro's career was not without conflict. The Tokugawa shogunate enforced censorship laws, known as the Kansei Reforms (late 1780s-early 1790s) and subsequent regulations, which aimed to control perceived extravagance and moral laxity in publications. Erotic prints (shunga) were officially banned, though produced and circulated clandestinely. Utamaro, a prolific creator of shunga, navigated these restrictions throughout his career.

A more serious confrontation occurred in 1804. Utamaro designed a series of prints depicting the 16th-century military leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi and his consorts, based on a popular, though historically inaccurate, book called Ehon Taikōki. Depicting recent historical figures, especially those related to the Tokugawa clan's predecessors or rivals, was strictly forbidden. Utamaro was arrested, interrogated, and sentenced to fifty days of being handcuffed (some accounts suggest imprisonment).

This punishment seems to have had a devastating effect on the artist. Released later in 1804, his spirit was reportedly broken. While he continued to produce prints, some critics observe a decline in the quality and emotional intensity of his work during these final years, suggesting a shift towards more formulaic or conventional depictions. The vibrant spark that characterized his golden age seemed diminished. Kitagawa Utamaro died just two years later, in 1806, in Edo. The exact cause of death is unknown, but the humiliation and psychological toll of his punishment likely contributed to his decline.

Utamaro's Enduring Influence in Japan

Within Japan, Utamaro's impact was immediate and lasting. He set a new standard for bijin-ga, emphasizing psychological portrayal and intimate observation. His innovations, particularly the popularization of the ōkubi-e format, were widely adopted by subsequent ukiyo-e artists. While later masters like Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) and Andō Hiroshige (1797-1858) would become more famous for landscapes, the influence of Utamaro's figure drawing and compositional sense can still be discerned.

The tradition of bijin-ga continued after Utamaro, carried on by his pupils and other artists like Keisai Eisen and Utagawa Kunisada, though arguably none quite matched the unique blend of elegance, sensuality, and psychological insight found in Utamaro's best work. His prints remained popular and were collected and admired throughout the 19th century, solidifying his position as one of the undisputed masters of the ukiyo-e genre. He captured an essential aspect of the Edo period's aesthetic and social life, particularly the world of its women.

Utamaro and the West: Fueling Japonisme

Perhaps Utamaro's most profound and far-reaching influence occurred posthumously and geographically distant – in Europe and America during the latter half of the 19th century. Following the opening of Japan to the West in the 1850s, Japanese art, particularly ukiyo-e prints, began to flood European markets. These prints, with their bold compositions, flat areas of color, unconventional perspectives, and focus on everyday life, were a revelation to Western artists struggling to break free from academic conventions.

Utamaro's works were among the most admired and collected. Artists associated with Impressionism and Post-Impressionism were particularly captivated. Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, Claude Monet, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and James McNeill Whistler, among others, fell under the spell of Japonisme. They were drawn to Utamaro's asymmetrical compositions, his use of cropping and close-ups (akin to his ōkubi-e), his elegant linearity, and his intimate portrayal of women in private moments.

Mary Cassatt, for instance, directly echoed Utamaro's themes of mothers and children and his intimate domestic scenes, adapting his compositional devices and flattened perspective in her own prints and paintings. Degas admired the candidness and unusual viewpoints in Utamaro's work, which resonated with his own depictions of dancers and women bathing. Van Gogh copied Japanese prints, including some attributed to or in the style of Utamaro, absorbing their approach to line and color. Toulouse-Lautrec's posters clearly show the influence of Japanese print composition and line work. Utamaro's emphasis on expressive line and decorative pattern profoundly impacted the development of Art Nouveau as well.

Utamaro's prints offered Western artists a new way of seeing and representing the world, validating their own experiments with form, color, and subject matter. His focus on the ephemeral, the everyday, and the intimate resonated deeply, contributing significantly to the visual language of modern Western art.

Legacy of a Master Observer

Kitagawa Utamaro remains a pivotal figure in the history of art. As a master of ukiyo-e, he refined the genre of bijin-ga, infusing it with unprecedented psychological depth and sensuality. His technical innovations, particularly his mastery of color printing and his pioneering use of the ōkubi-e format, expanded the expressive possibilities of the woodblock print. He captured the allure and complexity of women in Edo Japan, from the heights of the Yoshiwara courtesans to the quiet moments of domestic life, with unparalleled sensitivity.

His life, marked by artistic triumph and eventual conflict with authority, reflects the dynamic and sometimes restrictive cultural environment of the late Edo period. While biographical details remain elusive, his artistic legacy is clear and substantial. His work provides invaluable insight into the aesthetics and social fabric of his time.

Furthermore, Utamaro's posthumous influence on Western art underscores the universal appeal of his vision. His unique way of observing and depicting the human form, particularly the female figure, transcended cultural boundaries, inspiring a generation of European artists and contributing fundamentally to the development of modern art. Kitagawa Utamaro was not just a master of the Japanese print; he was a world artist whose keen eye and elegant hand continue to captivate and inspire.