Saburosuke Okada stands as a pivotal figure in the history of modern Japanese art. Born in Saga Prefecture during the dynamic Meiji era (1868-1912), a period of profound societal and cultural transformation as Japan opened its doors to the West, Okada became a leading proponent of yōga, or Western-style painting. His career, spanning several decades into the Shōwa period, was characterized by a delicate and sophisticated fusion of Western artistic techniques with an innate Japanese aesthetic sensibility, particularly evident in his renowned depictions of women. As an artist, educator, and organizer, Okada left an indelible mark on the trajectory of Japanese art, navigating the complex interplay between indigenous traditions and foreign influences.

Early Artistic Inclinations and Formative Training

Okada Saburosuke's artistic journey began in a Japan eagerly absorbing Western knowledge. His formal art education commenced in 1887 when he entered the studio of Yukihiko Soyama , a painter known for his Western-style works. This initial exposure laid the groundwork for his future pursuits. By the early 1890s, Okada sought further instruction under Keiichirō Kume , another significant yōga painter who had himself studied in France. Kume, along with his contemporary Seiki Kuroda , was instrumental in introducing French academic and Impressionist-influenced styles to Japan.

Under Kume's tutelage, Okada honed his skills in oil painting, a medium still relatively new and exciting in Japan. This period was crucial for Okada, as he began to assimilate the foundational techniques of Western art. The influence of these early mentors, particularly their emphasis on direct observation and realistic representation, shaped Okada's developing artistic voice. He was part of a generation of artists grappling with how to adapt these foreign methods to express Japanese subjects and sensibilities.

The Parisian Sojourn: Immersion in the European Art World

A defining moment in Okada's career came in 1897 when he, along with Seiki Kuroda and others, played a role in founding the Hakubakai . This influential art association was established by painters returning from study in France, aiming to promote newer trends in Western art, particularly plein-air painting and a brighter palette, in contrast to the more conservative styles previously dominant. Okada's involvement with the Hakubakai placed him at the forefront of the yōga movement.

Recognizing his talent and potential, the Japanese Ministry of Education sponsored Okada to travel to France for advanced study in 1902. Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world, offered unparalleled opportunities for artistic growth. Okada enrolled in the atelier of Raphael Collin (1850-1916), a prominent academic painter known for his idealized depictions of female figures and his gentle, harmonious color schemes. Collin's style, which blended academic precision with a softer, almost Symbolist sensibility, resonated deeply with Okada.

During his time in Paris, Okada diligently studied oil painting techniques and also immersed himself in the art of printmaking, particularly etching and other metal plate techniques. He absorbed the artistic currents of the city, visiting museums, galleries, and interacting with the vibrant international art community. This period abroad was not merely about technical acquisition; it was a profound cultural immersion that broadened his artistic horizons and refined his aesthetic judgment. Artists like James McNeill Whistler and members of the Symbolist movement also likely informed his evolving tastes.

Return to Japan: A Master's Contribution to Yōga

Upon his return to Japan in 1902, Okada Saburosuke was appointed a professor at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts , now the Tokyo University of the Arts. This prestigious position allowed him to exert considerable influence on subsequent generations of Japanese artists. He taught alongside other luminaries of the yōga world, including his former mentor Seiki Kuroda and his contemporary Takeji Fujishima .

At the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, Okada became known for his meticulous teaching methods and his emphasis on solid draftsmanship and refined technique. He advocated for a style that, while rooted in Western academic traditions, was also imbued with a distinct Japanese grace and subtlety. His own work began to mature, showcasing a remarkable ability to capture the delicate beauty of his subjects, particularly women.

Okada's artistic style is often described as Wayo-setchu , an eclectic blend of Japanese and Western elements. He masterfully applied the principles of Western realism, including anatomical accuracy, perspective, and chiaroscuro, but his choice of palette, the gentle expressions of his figures, and the overall lyrical mood of his paintings often evoked a Japanese aesthetic. He avoided the dramatic intensity of some Western art, opting instead for harmony, elegance, and a quiet introspection.

Signature Works and Thematic Focus: The Elegance of Femininity

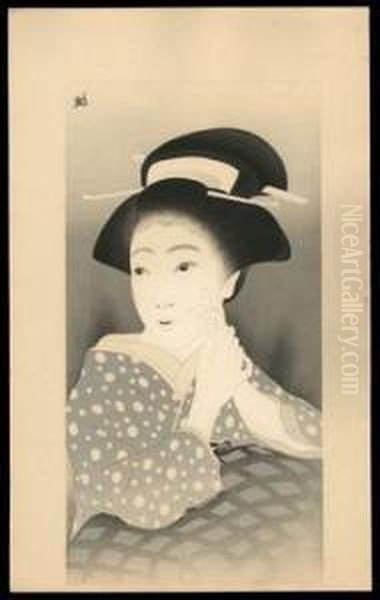

Okada Saburosuke is perhaps best known for his portraits and genre scenes featuring women, often referred to as bijin-ga in a Western-style context. These works are characterized by their refined execution, delicate coloration, and sensitive portrayal of female subjects.

One of his most celebrated masterpieces is "Portrait of a Lady (Wife of a certain Mr. Kume)" (1907), also known as "Portrait of Mrs. Kume" or "Some Lady's Portrait" . This painting, exhibited at the first Bunten exhibition (the annual art exhibition sponsored by the Ministry of Education), showcases his skill in capturing both the likeness and the inner grace of the sitter. The soft lighting, harmonious colors, and the serene expression of the woman are hallmarks of his mature style.

Another iconic work is "Before the Bath" , completed in 1931. This painting depicts a nude woman in an outdoor setting, subtly blending the Western tradition of the female nude with Japanese sensibilities regarding nature and bathing. The figure is rendered with classical grace, yet the atmosphere is imbued with a gentle, almost dreamlike quality. The inclusion of Japanese flora, like the matsumushisō (scabiosa), adds a layer of local symbolism.

"Nude Woman" , painted in 1935, is another significant example of his engagement with the nude. The work is celebrated for its depiction of translucent, pearly skin and its ethereal atmosphere. Okada’s nudes were generally not overtly sensual but rather focused on idealized beauty and formal elegance, reflecting his academic training under Collin.

Other notable works include "Cherry Orchard" , which demonstrates his skill in landscape and his ability to infuse scenes with a poetic lyricism, and "A Lady in Red" , which highlights his sophisticated use of color and composition in portraiture. His "Portrait of Mrs. Okada Yachiyo" , depicting his wife, is a tender and insightful portrayal that further exemplifies his mastery in capturing personality.

Contributions to Printmaking and Art Education

Beyond his achievements in oil painting, Okada Saburosuke made significant contributions to the field of modern Japanese printmaking. Having studied etching in Paris, he was keen to promote this and other Western printmaking techniques in Japan. In 1931, he played a crucial role in founding the Nihon Hanga Kyōkai and served as its first chairman. This organization was vital as it successfully united artists from the Yōfū Hangakai (Western-Style Printmakers' Association) and the Sōsaku Hanga (Creative Print) movement, fostering a collaborative environment for the advancement of Japanese printmaking on an international stage.

His own print work, such as "Osuhime" (おすひめ), created for "The Complete Works of Takeuchi Seihō" , demonstrates his delicate touch in this medium. The woodblock print "Heroine Osan" , completed in 1923 and included in the "Akamatsu Collection," was highly sought after by collectors and showcased his ability to adapt his refined aesthetic to the woodblock medium.

As an educator, Okada's influence was profound. He taught at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts for many years, shaping the skills and artistic philosophies of numerous students. Among those who studied under him or were significantly influenced by his teaching were Chihiro Iwasaki (いわさきちひろ), who later became a renowned illustrator of children's books, and Hasui Kawase , who, though primarily known for his shin-hanga woodblock prints, initially studied Western-style painting with Okada. The Taiwanese artist Yan Shuilong also benefited from Okada's guidance during his studies in Japan.

Furthermore, Okada co-founded the Hongō Painting Institute with his colleague Takeji Fujishima. This private art school provided an alternative venue for art education and further contributed to the dissemination of Western painting techniques and aesthetics in Japan. His dedication to teaching ensured that his artistic principles and technical expertise were passed on, contributing to the richness and diversity of Japanese art in the 20th century. Other artists who were part of his broader circle or who benefited from the environment he helped create include Eisaku Wada , Fusetsu Nakamura , and Shigeru Aoki , all key figures in the yōga movement.

Artistic Circles, Collaborations, and Contemporaries

Saburosuke Okada was an active participant in the Japanese art world, not only as a painter and educator but also as a member and founder of influential art societies. His early involvement with the Hakubakai, alongside Seiki Kuroda, Keiichirō Kume, Takeji Fujishima, and others, was crucial. The Hakubakai championed a brighter, more Impressionistic style of painting, influenced by French plein-air artists like Raphaël Collin himself, and artists such as Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret. This group provided a vital platform for artists to exhibit their work and exchange ideas, significantly shaping the direction of yōga in the late Meiji period.

His relationships with contemporaries were multifaceted. With figures like Kuroda and Fujishima, there was a sense of shared mission in establishing Western-style painting in Japan. They studied abroad, brought back new knowledge, and worked to institutionalize yōga through teaching and exhibitions. While there was undoubtedly a spirit of collegiality, the art world is also inherently competitive. Artists vied for recognition in major exhibitions like the Bunten (later Teiten and Shin-Bunten), and stylistic differences naturally led to varied artistic paths.

Okada's refined, academic style, with its emphasis on elegance and technical polish, contrasted with the more rugged or expressive styles of some other yōga painters, such as Ryūsei Kishida in his later phases, or the more avant-garde explorations that emerged later in the Taishō and early Shōwa periods. However, Okada's consistent dedication to his vision of beauty earned him widespread respect and numerous accolades, including the prestigious Order of Culture in 1937, one of Japan's highest honors for artistic and cultural contributions. He also worked alongside other prominent artists of his time like Umehara Ryūzaburō and Yasui Sōtarō , who also studied in France and became leading figures in Japanese modern art, though their stylistic trajectories often diverged from Okada's more classical approach.

Art Historical Evaluation and Points of Discussion

In the annals of Japanese art history, Saburosuke Okada is lauded as a master of yōga, particularly for his elegant and sensitive portrayals of women. He successfully navigated the challenge of adapting Western oil painting techniques to a Japanese cultural context, creating a body of work that is both technically accomplished and aesthetically pleasing. His paintings are celebrated for their harmonious compositions, subtle color palettes, and the graceful demeanor of his subjects.

However, like many artists of his time who embraced Western styles, Okada's work was occasionally subject to contemporary and later discussions regarding "Westernization." Some critics, particularly those championing Nihonga (Japanese-style painting) or more nationalistic artistic expressions, might have viewed the enthusiastic adoption of Western techniques as a dilution of indigenous artistic traditions. The debate over how to modernize Japanese art while retaining a distinct cultural identity was a central theme of the Meiji, Taishō, and early Shōwa periods.

The depiction of the female nude, a common subject in Western academic art, also presented complexities in the Japanese context. While Okada’s nudes were generally idealized and devoid of overt eroticism, the public display of nude figures was still a relatively new and sometimes controversial phenomenon in Meiji and Taishō Japan. Artists like Okada, by engaging with this genre, were participating in a broader cultural dialogue about changing social norms, artistic freedom, and the reception of Western cultural forms. His approach, influenced by Collin's chaste nudes, aimed for a universal, aestheticized beauty rather than provocation.

Despite these discussions, Okada's enduring legacy is that of a refined and influential artist who significantly contributed to the establishment and development of Western-style painting in Japan. His commitment to beauty, his technical mastery, and his dedication to education secured his place as a foundational figure in modern Japanese art.

Later Years and Enduring Influence

Saburosuke Okada continued to paint and teach throughout his later years, remaining an esteemed figure in the Japanese art world. He consistently participated in major exhibitions, and his work was widely collected. His influence extended not only through his direct students but also through the broader artistic climate he helped to shape. The institutions he was part of, such as the Tokyo School of Fine Arts and the Japan Print Association, continued to flourish, fostering new generations of artists.

His dedication to a refined aesthetic, which balanced Western techniques with a Japanese sensibility, provided a model for artists seeking to create a modern yet culturally resonant art form. Even as more radical artistic movements emerged in Japan, Okada's classicism remained a touchstone of elegance and technical skill.

Saburosuke Okada passed away in 1939, leaving behind a rich legacy of paintings and prints, as well as a significant impact on art education. His works are now held in major museum collections across Japan, including the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, the Saga Prefectural Art Museum (his home prefecture), and many others, where they continue to be admired for their timeless beauty and historical importance.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Grace and Synthesis

Saburosuke Okada's life and work represent a crucial chapter in the modernization of Japanese art. As a pioneer of yōga, he masterfully synthesized the techniques and aesthetics of Western academic painting with an inherent Japanese grace. His elegant depictions of women, his contributions to printmaking, and his long and influential career as an educator solidified his status as one of the most important Japanese artists of the early 20th century. Okada navigated the cultural currents of his time with sophistication, creating an art that was both international in its language and deeply personal in its expression of beauty. His legacy endures in his captivating artworks and in the continuing dialogue between tradition and modernity in Japanese art.