Grace Henry stands as a significant figure in the landscape of early 20th-century Irish art. Born Emily Grace Mitchell in Scotland, she became intrinsically linked with the artistic developments in Ireland, particularly through her marriage to the renowned painter Paul Henry and her own distinctive contribution as a colourist and modernist painter. Her life (1868-1953) spanned a period of immense change, both socially and artistically, and her work reflects a journey through various influences, locations, and personal experiences, culminating in a style celebrated for its vibrancy, emotional depth, and expressive freedom. Though sometimes overshadowed by her husband's fame, Grace Henry forged her own path, leaving behind a body of work that continues to captivate audiences and assert her place as a key female artist of her generation.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Emily Grace Mitchell was born in Peterhead, Aberdeenshire, Scotland, in 1868. Her background was one of relative comfort and intellectual engagement; she was the second of ten children born to Reverend John Mitchell, a Presbyterian minister. This upbringing in a large, educated family likely provided a foundation for her later pursuits, although the specific details of her early encouragement in the arts remain somewhat scarce. What is clear is that she possessed a strong artistic inclination that led her to seek formal training beyond Scotland.

Her artistic education took her to the continent, a common path for aspiring artists of the era seeking exposure to more progressive teaching methods and styles than often available in Britain. She studied first at the Blanc Garrins Academy in Brussels, immersing herself in the Belgian art scene. Following this, she moved to Paris, the undisputed centre of the art world at the time. In Paris, she enrolled at the Delecluse Academy, further honing her skills and absorbing the influences swirling through the city, from the lingering legacy of Impressionism to the burgeoning Post-Impressionist movements. It was during this formative period in Paris that her life took a decisive turn upon meeting a fellow artist, the Irish painter Paul Henry.

Marriage and Early Career

The encounter in Paris blossomed into a relationship, and in 1903, Emily Grace Mitchell married Paul Henry, thereafter becoming known professionally as Grace Henry. Their partnership was both personal and artistic, and they initially based themselves in England. Grace began to establish her career, exhibiting her work in London. Notably, she showed paintings at the prestigious Royal Academy (RA), a significant achievement for any artist, particularly a woman, at that time.

Her early work, influenced by her training and the prevailing tastes, sometimes showed an affinity for the tonal harmonies and atmospheric effects championed by artists like James McNeill Whistler. Whistler's subtle nocturnes and evocative cityscapes had a profound impact on many artists of the period, and traces of this aesthetic can be discerned in some of Grace Henry's initial output. However, her own distinct voice was already beginning to emerge. A joint exhibition with Paul Henry at the Baillie Gallery in London in 1910 marked an important moment, showcasing their work side-by-side and highlighting Grace's burgeoning talent, particularly her innate sense as a colourist.

The Achill Island Years

A pivotal moment in both Grace and Paul Henry's lives and artistic careers occurred around 1912 (some sources suggest 1910, but 1912 is frequently cited for the permanent move). Seeking a more authentic, less conventional life and inspired by J.M. Synge's writings about the Aran Islands, they travelled to Achill Island, off the coast of County Mayo in the west of Ireland. Initially intended as a short holiday, the experience proved transformative. They were captivated by the rugged landscape, the dramatic Atlantic light, and the traditional way of life of the islanders. They decided to stay, making Achill their home for the better part of the next decade, until 1919.

This period on Achill Island was profoundly influential for Grace Henry's art. The intense colours of the landscape – the deep blues and greens of the sea and land, the shifting purples of the mountains, the earthy tones of the turf bogs, and the bright flashes of colour in the islanders' shawls – seemed to liberate her palette. Her style moved decisively away from the Whistlerian subtlety towards a much bolder, more expressive use of colour and a freer application of paint. She immersed herself in depicting the island's scenery and the daily lives of its inhabitants.

Works from this period, such as The Top of the Hill (c. 1914-15), now housed in the Limerick City Gallery of Art, exemplify this shift. This painting captures the windswept beauty of the island with vigorous brushwork and a rich palette. Another work, Strand, Achill (c. 1910-12), focuses on the coastal landscape, demonstrating her keen observation of natural forms and light. She painted the cottages, the fields, the women digging potatoes, the men working with boats or turf, capturing the essence of their connection to the land with empathy and a distinct lack of sentimentality. Her Achill paintings are characterised by their energy, their vibrant colour harmonies, and their direct, unpretentious approach to the subject matter.

Developing Modernism and the Dublin Scene

While based in the relative isolation of Achill, Grace Henry remained connected to the broader art world, particularly the developing scene in Dublin. The early 20th century was a time of cultural ferment in Ireland, with the Celtic Revival influencing literature and the arts, and a growing interest in modernist ideas arriving from the continent. Grace and Paul Henry were part of a generation seeking to forge a distinctly modern Irish art.

In 1920, shortly after leaving Achill and settling in Dublin, Grace Henry played a crucial role, alongside Paul Henry and other artists including Letitia Marion Hamilton and possibly figures associated with the modernist circle like Mainie Jellett and Evie Hone (though founding member lists can vary), in establishing the Society of Dublin Painters. This group aimed to provide an alternative exhibition venue to the more conservative Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA), creating a space where artists exploring more modern styles could show their work regularly. The Society held frequent group and solo exhibitions at their premises on St Stephen's Green, becoming an important hub for modernist activity in the city.

Grace Henry exhibited regularly with the Society of Dublin Painters during the early 1920s. Her work from this period continued to evolve, showing an increasing confidence and experimentation. Her bold use of colour and simplified forms placed her at the forefront of Irish modernism. Her paintings were included in significant exhibitions showcasing contemporary Irish art, both domestically in Dublin and Belfast, and internationally, such as the Exposition d’Art Irlandais held in Paris in 1922. Her style, while individual, resonated with the explorations of colour and form being undertaken by contemporaries like Mainie Jellett, though often retaining a more representational core compared to Jellett's move towards Cubism. She was certainly aware of, and contributing to, the dialogue around modern art in Ireland, alongside major figures like Jack B. Yeats, whose expressive style also defined Irish modernism.

Travels and Transitions

The mid-1920s marked a period of significant personal change for Grace Henry. Her relationship with Paul Henry deteriorated, and they separated, although they never formally divorced. This separation led Grace to embark on a more independent and peripatetic phase of her life. She travelled extensively throughout the 1920s and 1930s, spending considerable time in Britain and on the continent, particularly in France and Italy. These travels provided fresh inspiration and subject matter for her art.

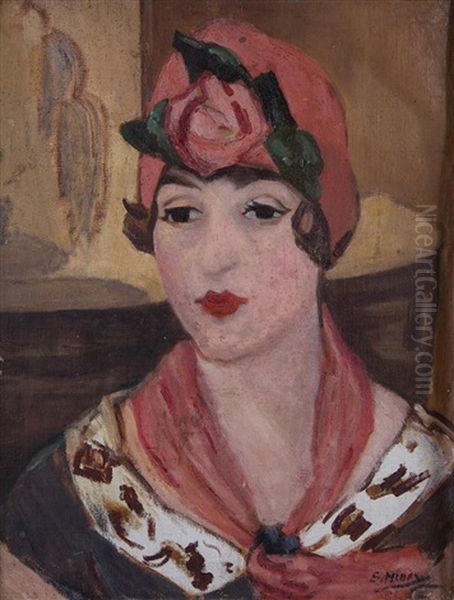

During this time, she formed a close relationship with the writer and politician Stephen Gwynn, who became a companion on some of her European travels. Her experiences abroad are reflected in paintings that capture the light and atmosphere of different locales. Works like La Parisienne (1924), a portrait imbued with a chic French sensibility, demonstrate her engagement with European culture and her ability to adapt her style to different subjects. Her travels likely reinforced the Post-Impressionist tendencies in her work, echoing the expressive colour and brushwork seen in artists like Van Gogh or Gauguin, or perhaps closer to home, the Irish Post-Impressionist Roderic O'Conor, who had worked directly with Gauguin's circle in Pont-Aven.

Despite her travels, she maintained her connections with the art scenes in London and Dublin, continuing to exhibit her work in both cities. This period reflects a mature artist, confident in her vision, exploring new environments while retaining the core elements of her style – the vibrant colour, the fluid brushwork, and the focus on capturing the essential character of her subjects, whether landscapes or people.

Artistic Style and Technique

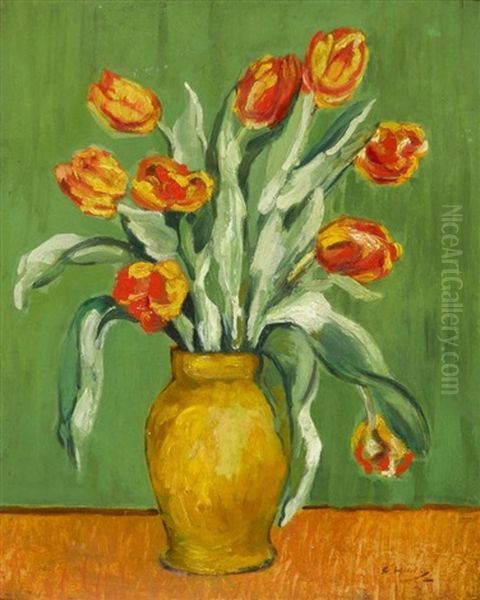

Grace Henry's artistic style is perhaps best defined by her mastery of colour. She was fundamentally a colourist, using colour not just descriptively but emotionally and structurally. Her palette was often bold and unconventional for the time, employing strong contrasts and harmonies to create vibrant and expressive compositions. She was known to use complementary colours, such as greens and reds, placed side-by-side to enhance their intensity, a technique considered quite avant-garde in the context of early 20th-century Irish painting.

Her brushwork was equally distinctive – fluid, energetic, and often visible. She applied paint with confidence, simplifying forms and focusing on the overall rhythm and movement of the composition rather than on minute detail. This technique lent her work a sense of immediacy and spontaneity. While influenced by Impressionism and Post-Impressionism, particularly in her handling of light and colour and her expressive brushwork, her style remained uniquely her own. It combined keen observation with a subjective, emotional response to the world around her.

She had a remarkable ability to simplify complex scenes down to their essential elements, capturing the core spirit of a place or the inner humanity of a person. Her portraits and figure studies, though perhaps less numerous than her landscapes, are noted for their psychological insight and their depiction of quiet dignity. This simplification of form and emphasis on expressive colour aligns her with broader European modernist trends, but her work always retained a strong connection to the representational world.

Subject Matter

Grace Henry's subject matter was diverse, reflecting her life experiences and travels. Landscapes formed a significant part of her output, particularly during her time on Achill Island. She captured the dramatic cliffs, rolling hills, turbulent seas, and vast skies of the west of Ireland with unparalleled vigour. Her Achill paintings are considered iconic representations of that landscape, standing alongside those of her husband, Paul, yet possessing their own distinct energy and chromatic brilliance.

Beyond Achill, she painted landscapes in other parts of Ireland, Britain, and continental Europe, always responding to the specific light and atmosphere of each location. Italy, with its sun-drenched vistas, provided a different palette and mood compared to the wildness of the Atlantic coast.

Figure studies and portraits also feature prominently in her work. On Achill, she painted the local people, often women, engaged in their daily tasks, capturing their resilience and connection to the environment. Later works include portraits like La Parisienne and studies of children, such as Boy School in Striped Blazer. In these works, her fluid brushwork and bold colour choices serve to highlight the personality and presence of the sitter, conveying a sense of their inner life and character. Her focus was often on capturing a sense of unassuming humanity and quiet dignity.

Later Career and Recognition

Throughout the 1930s and 1940s, Grace Henry continued to paint and exhibit, primarily in Dublin and London. Although she may have been less visible than in the formative Achill and Dublin Painters Society years, she remained a respected figure in the art world. Her work continued to be acquired by collectors and institutions. While perhaps not achieving the same level of establishment recognition as some of her male contemporaries, like the highly successful portraitist Sir William Orpen or the established landscape painter Nathaniel Hone the Younger, her contribution was acknowledged.

A significant mark of recognition came late in her life. In 1949, she was elected an Honorary Member of the Royal Hibernian Academy (RHA). While not a full member, this honorary status conferred by Ireland's leading academic art institution was a testament to her standing and lifelong contribution to Irish art. It acknowledged her importance within the artistic community, even though her more modernist leanings had earlier placed her somewhat outside the RHA's traditional orbit.

She continued to paint until shortly before her death in Dublin in 1953. Her passing marked the end of a long and productive career that had significantly enriched the tapestry of Irish art.

Legacy and Collections

Grace Henry's legacy is that of a pioneering modernist painter and an exceptional colourist within the Irish context. She navigated the complexities of being a female artist in the early 20th century and forged a distinct artistic identity, separate from but connected to her famous husband. Her work provides a vital perspective on Irish landscape and life, particularly her vibrant and empathetic depictions of Achill Island. Her bold use of colour and expressive technique influenced subsequent generations of Irish artists.

Her importance has been increasingly recognized in recent decades through exhibitions and scholarly attention. The publication of studies such as Dr. James Cruickshank's Grace Henry: The Person and the Art has helped to further illuminate her life and work, securing her position in Irish art history. Her paintings are held in major public collections across Ireland, including the National Gallery of Ireland, the Hugh Lane Gallery Dublin City, Limerick City Gallery of Art, the Crawford Art Gallery in Cork, the Royal Hibernian Academy Collection, and the Trinity College Dublin Art Collections.

Her work also appears periodically on the art market, demonstrating continued collector interest. The sale of La Parisienne for €3,000 in 2017, while perhaps modest compared to prices for works by Paul Henry or Jack B. Yeats, indicates an ongoing appreciation for her unique contribution. She remains a key figure for understanding the development of modernism in Ireland and the vital role played by women artists in shaping its course.

Conclusion

Grace Henry's artistic journey took her from the academies of Brussels and Paris to the rugged landscapes of Achill Island and the bustling art scenes of London and Dublin. Born in Scotland, she became an integral part of Irish art history, contributing a unique vision characterized by vibrant colour, fluid brushwork, and a deep empathy for her subjects. As a co-founder of the Society of Dublin Painters, she actively participated in the promotion of modernism in Ireland. Her work stands as a testament to her individual talent, offering a perspective that is both aesthetically compelling and historically significant. Alongside contemporaries like Paul Henry, Jack B. Yeats, Mainie Jellett, and Mary Swanzy, Grace Henry helped to define the course of Irish painting in the 20th century, leaving a legacy that continues to be celebrated for its artistic merit and its spirited depiction of life and landscape.