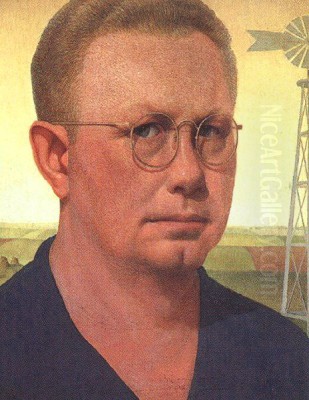

Grant Wood stands as one of the most recognizable and significant figures in twentieth-century American art. Primarily associated with the Regionalist movement, Wood dedicated his career to depicting the landscapes, people, and values of the American Midwest, particularly his native Iowa. His meticulously crafted paintings, most famously American Gothic, have become ingrained in the national consciousness, serving as both celebrations and subtle critiques of rural American life. His unique style, blending the precision of Northern European Old Masters with distinctly American subject matter, created a visual language that resonated deeply during a period of national introspection and change, particularly the Great Depression. Understanding Grant Wood requires exploring his formative experiences, his artistic evolution, his engagement with contemporaries, and the enduring, often complex, legacy of his work.

Early Life and Formative Influences

Grant DeVolson Wood was born in 1891 on a farm near Anamosa, Iowa. His early years were steeped in the rhythms and realities of rural existence, an experience that would profoundly shape his artistic vision. The Midwestern landscape, with its rolling hills, cultivated fields, and distinct architecture, became a recurring motif in his later work. His father's death when Grant was ten years old prompted the family's move to the larger town of Cedar Rapids, a transition that marked a significant shift in his environment but did not erase the deep imprint of his farm beginnings.

His mother, Hattie Weaver Wood, played a crucial role in encouraging his artistic talents. From a young age, Wood displayed an aptitude for drawing and making objects. In Cedar Rapids, he gained exposure to a wider range of cultural influences and began formal art training. He involved himself in various artistic pursuits during high school and briefly attended the Handicraft Guild in Minneapolis, a school focused on Arts and Crafts principles, in 1910. These early experiences instilled in him a strong sense of craftsmanship and design, which remained evident throughout his painting career.

Wood's initial forays into the professional art world involved various jobs, including metalwork and interior design. He also taught art in Cedar Rapids public schools. This period saw him experimenting with different styles, initially leaning towards the Impressionist and Post-Impressionist aesthetics popular at the time, reflecting the influence of artists whose work he would have encountered through reproductions and limited exhibitions available in the Midwest. His lifelong friendship with fellow Cedar Rapids artist Marvin Cone also began during this period; they would later share a studio and travel to Europe together, mutually supporting each other's artistic development.

Education and European Sojourns

Wood sought further formal training at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago intermittently between 1913 and 1916. Chicago provided greater exposure to contemporary art trends and museum collections. His early paintings from this era often reflect an Impressionistic approach, characterized by looser brushwork and an emphasis on light and atmosphere, akin to the works of French masters like Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, whose styles were becoming increasingly influential in American art schools.

A pivotal moment in Wood's development came with his trips to Europe. He traveled there four times between 1920 and 1928. His first trip, in 1920, was with Marvin Cone, primarily spent in Paris soaking up the bohemian atmosphere and visiting museums. Subsequent trips allowed him to study at the Académie Julian in Paris. While initially drawn to Impressionism, his European experiences, particularly his time in Germany in 1928, catalyzed a dramatic stylistic shift.

During a trip to Munich to oversee the fabrication of a stained-glass window he designed for the Cedar Rapids Veterans Memorial Building, Wood encountered the highly detailed realism of 15th and 16th-century Northern European masters, particularly German and Flemish artists like Jan van Eyck, Hans Memling, and Albrecht Dürer. He was profoundly struck by their meticulous technique, clarity of form, sharp focus, and rich detail. This encounter proved transformative, leading him to abandon the looser, atmospheric style of Impressionism in favor of a more precise, sharply defined realism. He recognized that this older tradition offered a way to depict his own world with clarity and conviction.

The Emergence of a Distinctive Style

Returning to Iowa after his 1928 trip, Grant Wood consciously decided to paint the subjects he knew best: the people and landscapes of his native Midwest. He famously stated, "All the good ideas I've ever had came to me while I was milking a cow." This wasn't just a folksy anecdote; it signaled a deliberate turning away from European avant-garde styles and a commitment to finding artistic value in his immediate surroundings. He began applying the meticulous techniques inspired by the Northern Renaissance masters to American themes.

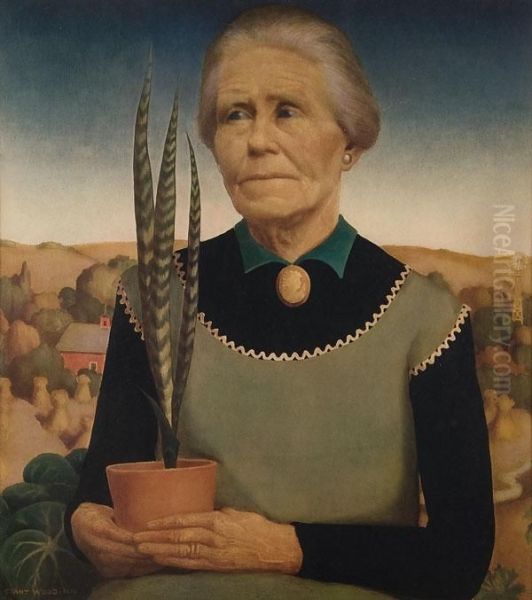

This new direction became evident in works like Woman with Plants (1929), a portrait of his mother, Hattie. The painting showcases the hard-edged precision, detailed rendering of textures (like the potted sansevieria plant), and formal composition that would become hallmarks of his mature style. The portrait possesses a stoicism and dignity that foreshadows the figures in his most famous work, created the following year.

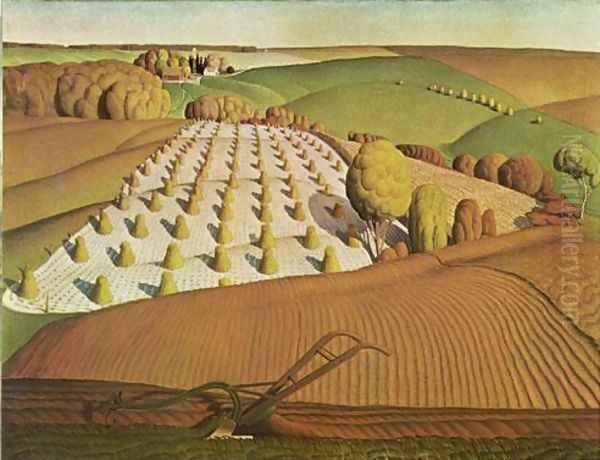

Wood's developing style was characterized by clarity, order, and a high degree of finish. He often simplified forms, particularly in his landscapes, creating stylized, almost decorative patterns of rolling hills and rounded trees. This wasn't photographic realism but a carefully constructed, idealized vision of the Midwest, rendered with painstaking detail. This unique fusion of Old Master technique and American subject matter set him apart and laid the groundwork for his role in the Regionalist movement.

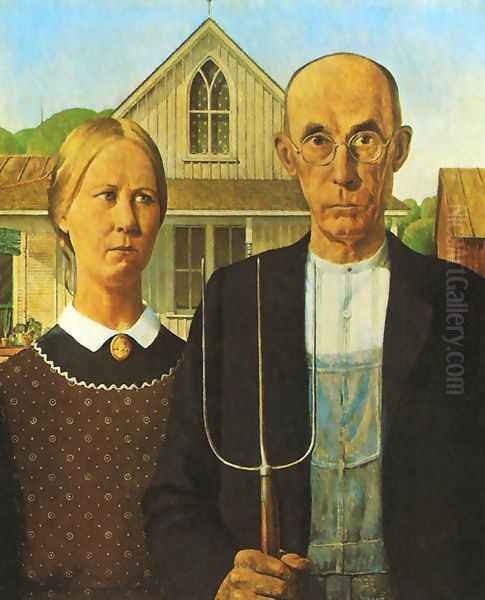

American Gothic: An Icon is Born

In 1930, Grant Wood created the painting that would catapult him to national fame and become one of the most iconic images in American art history: American Gothic. The inspiration came from a small Carpenter Gothic house he saw in Eldon, Iowa, with its distinctive arched window on the upper floor. He was struck by the contrast between the modest house and the "pretentious" architectural detail, imagining the kind of "severe" people he thought should live there.

He asked his sister, Nan Wood Graham, and his dentist, Dr. Byron McKeeby, to pose as the figures, a farmer and his daughter (though often misinterpreted as husband and wife). Wood elongated their faces and rendered them with the stern, unsmiling expressions he associated with early American portraiture and the perceived character of Midwestern pioneers. The man holds a pitchfork, symbolizing manual labor, its tines echoing the vertical lines of his overalls and the window frame above. The woman looks slightly askance, wearing a colonial-print apron.

The painting was submitted to the annual exhibition at the Art Institute of Chicago, where it won a bronze medal and a $300 prize. Its reception was immediate and widespread, though mixed. Some Iowans were offended, feeling it portrayed them as grim and backward. Nationally, however, it was widely reproduced and quickly became a symbol of American fortitude, rural values, and pioneer spirit, particularly resonant during the hardship of the Great Depression. Its ambiguity—is it a celebration or a satire?—has fueled endless interpretations and parodies, cementing its place in American visual culture.

Regionalism and the American Scene

American Gothic's success coincided with the rise of Regionalism, an art movement that dominated American art during the 1930s. Regionalism, also known as American Scene Painting, emphasized depictions of everyday American life, particularly in rural and small-town settings. It represented a conscious turning away from European modernism (especially abstraction) and a desire to create a distinctly American art rooted in national experience.

Grant Wood, along with Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri and John Steuart Curry of Kansas, formed the triumvirate of leading Regionalist painters. While sharing a focus on American themes, their styles differed. Benton's work was characterized by dynamic, swirling compositions and exaggerated figures, often depicting scenes of labor and folklore. Curry focused on the dramatic aspects of rural life, including storms and religious fervor. Wood's style was more static, precise, and often imbued with a quiet, sometimes unsettling, stillness.

These artists sought to capture the character and values of the American heartland, often celebrating themes of hard work, community, and resilience. Their work found favor with a public weary of the Depression and seeking affirmation of traditional American identity. Other artists associated with the broader American Scene movement included Charles Burchfield, known for his moody depictions of small-town Ohio, and Reginald Marsh, who captured the bustling energy of urban life in New York City. Regionalism provided a comforting, accessible alternative to the perceived elitism and foreignness of abstract art.

Key Themes and Motifs in Wood's Work

Beyond the iconic American Gothic, Grant Wood explored several recurring themes and motifs that define his artistic vision. His deep connection to the Iowa landscape is paramount. Paintings like Stone City, Iowa (1930), Fall Plowing (1931), and Young Corn (1931) present an idealized, almost dreamlike vision of the Midwestern countryside. The hills are perfectly rounded, the trees are stylized and lollipop-like, and the fields are rendered with meticulous, patterned detail. This landscape is orderly, fertile, and bathed in a clear, even light, suggesting harmony and abundance, though some critics find an underlying artificiality or even claustrophobia in this controlled perfection.

The theme of labor, particularly agricultural work, is central to Wood's oeuvre. Dinner for Threshers (1934) depicts a communal meal during harvest time, celebrating the collective effort and bounty of farm life. The figures are sturdy and dignified, embodying the virtues of hard work and community solidarity. The composition is carefully arranged, emphasizing order and ritual.

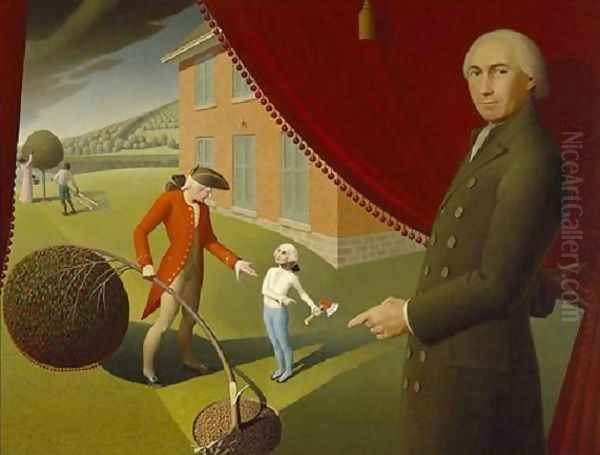

Wood also turned his attention to American history and mythology, often with a satirical or gently critical eye. Daughters of Revolution (1932) portrays three aging members of the Daughters of the American Revolution organization, looking prim and self-important before a reproduction of Emanuel Leutze's Washington Crossing the Delaware. The painting subtly mocks their perceived snobbery and detachment from the revolutionary spirit they claim to uphold. The Midnight Ride of Paul Revere (1931) presents a bird's-eye view of the legendary event, transforming it into an almost toy-like scene, questioning the heroic scale of national myths. Parson Weems' Fable (1939) humorously depicts the apocryphal story of George Washington and the cherry tree, with Parson Weems himself pulling back a curtain to reveal the scene, highlighting the constructed nature of historical narratives.

Other Major Works

While American Gothic remains his most famous painting, several other works are crucial to understanding Grant Wood's artistic range and development. Arnold Comes of Age (1930) is a sensitive portrait marking a young man's transition, set against a stylized landscape that includes symbolic elements like crossing paths. Appraisal (1931) depicts a farm woman presenting a chicken to a more sophisticated town woman, highlighting the cultural and economic tensions between rural and urban life during a period of transition. The contrasting appearances and subtle expressions of the two women invite interpretation regarding value, class, and changing societal norms.

Death on Ridge Road (1935) introduces a rare note of overt drama and danger into Wood's typically serene world. A large black truck crests a hill, looming over a smaller red car, suggesting an impending collision. The stylized landscape elements remain, but the sense of imminent threat creates a powerful tension, perhaps reflecting underlying anxieties beneath the placid surface of Midwestern life. These works demonstrate Wood's ability to infuse his detailed style with psychological depth and social commentary, moving beyond simple depictions of rural scenery.

The Stone City Art Colony and Teaching

Grant Wood was not only a painter but also an active participant in the artistic community, particularly through teaching and organizing. In 1932 and 1933, during the depths of the Great Depression, he helped establish the Stone City Art Colony and Art School near Cedar Rapids. Co-founded with Edward Rowan, director of the Little Gallery of Cedar Rapids, and others, the colony aimed to provide artists with an affordable place to live, work, and study during difficult economic times.

The colony attracted artists and students from across the country, fostering a creative environment centered on Regionalist principles – encouraging artists to paint their local surroundings. Wood was a charismatic and central figure at Stone City, known for his overalls and hands-on approach. Although short-lived due to financial difficulties, the colony was an important experiment in communal artistic living and a significant hub for Regionalism in the Midwest.

In 1934, Wood was appointed director of the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) for Iowa, a New Deal program designed to employ artists. Later that year, he joined the faculty of the School of Art at the University of Iowa in Iowa City. He was a popular teacher, encouraging students to develop strong technical skills and to find subjects in their own experiences. However, his tenure was marked by conflict with colleagues who favored European modernism and abstraction, viewing Wood's Regionalism as provincial and outdated. This academic dispute, coupled with personal issues, eventually led to him taking a leave of absence shortly before his death.

Personal Life and Contextual Complexities

Grant Wood's personal life adds another layer of complexity to understanding his work and career. He was a homosexual man living in a time and place where this was deeply stigmatized and hidden. This aspect of his identity has been increasingly discussed by art historians, particularly since the late 20th century, prompting re-readings of his work. Some scholars suggest that the meticulous control, stylized forms, and occasional satirical distance in his paintings might reflect the coded expressions and guardedness required by his personal circumstances.

The intense scrutiny and pressure he faced likely contributed to his decision to marry Sara Sherman Maxon in 1935. The marriage was reportedly tumultuous and unhappy, ending in divorce in 1939. His sister, Nan Wood Graham (the female model in American Gothic), remained a close confidante and fiercely protective figure throughout his life. After his death from pancreatic cancer in 1942, just shy of his 51st birthday, Nan became a dedicated guardian of his legacy, managing his estate and promoting his reputation, sometimes shaping the narrative around his life and work. The tension between Wood's public persona as the quintessential Midwestern artist and his private life continues to inform interpretations of his art.

Contemporaries and Artistic Comparisons

Placing Grant Wood within the context of his contemporaries helps illuminate his unique position. His relationship with fellow Regionalists Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry was one of shared goals but distinct styles. While they collectively championed American subjects, Wood's meticulous, almost miniaturist technique contrasted sharply with Benton's energetic, mural-like approach and Curry's focus on dramatic action.

Compared to Edward Hopper, another major American realist of the era, Wood's work offers a different perspective. Hopper focused primarily on urban and suburban scenes, exploring themes of isolation, alienation, and the psychological weight of modern life. While both artists often depicted solitary figures or quiet scenes, Hopper's mood is typically one of melancholy or unease, whereas Wood's, even when potentially satirical, often maintains a surface of order and stability.

Wood's idealized vision of America stands in contrast to the more illustrative, sentimental depictions found in the work of Norman Rockwell, though both artists tapped into a popular desire for images reflecting American values. Unlike Rockwell, Wood's work often contains layers of ambiguity and subtle critique beneath the polished surface. His commitment to realism also set him against the rising tide of abstraction championed by artists like Georgia O'Keeffe or Stuart Davis, and later the Abstract Expressionists like Jackson Pollock, who would come to dominate the post-war American art scene. His style can also be seen as a precursor, in some ways, to the detailed realism of later artists like Andrew Wyeth, although Wyeth's work possesses a different psychological tenor and regional focus (Pennsylvania and Maine).

Critical Reception and Evolving Legacy

The critical reception of Grant Wood's art has fluctuated significantly over time. During the 1930s, he enjoyed immense popularity, celebrated as a truly American artist capturing the spirit of the heartland. American Gothic became an instant sensation, widely reproduced and embraced by the public. Regionalism was lauded for providing accessible, affirmative images during a time of national crisis.

However, even during his lifetime, critics debated the meaning and merit of his work. Was American Gothic a celebration or a satire? Was his idealized landscape painting genuine affection or sophisticated irony? Some modernist critics dismissed Regionalism altogether as provincial, illustrative, and nationalistic, lacking the formal innovation and universal concerns of European avant-garde art. Figures associated with the New York School, like critic Clement Greenberg, would later champion Abstract Expressionism partly as a reaction against the perceived limitations of Regionalism.

After World War II, with the international ascendancy of Abstract Expressionism, Wood's reputation, along with that of Benton and Curry, declined sharply. Regionalism was often viewed as a nostalgic, conservative, and artistically insignificant interlude. For several decades, Wood's work was largely relegated to the status of popular culture icon (American Gothic) rather than serious art historical study.

Beginning in the late 20th century, however, a critical reappraisal of Grant Wood began. Art historians started to explore the complexities and ambiguities within his work, moving beyond simplistic labels of celebration or satire. Exhibitions and scholarly publications examined his sophisticated engagement with art history, his technical mastery, the social and economic commentary embedded in paintings like Appraisal, and the potential influence of his personal life and sexuality on his art (queer theory interpretations). His work is now often seen as a nuanced reflection on American identity, grappling with themes of tradition versus modernity, rural versus urban life, myth versus reality, and conformity versus individuality.

Enduring Significance

Grant Wood's legacy remains potent and multifaceted. He created some of the most indelible images in American art, works that continue to resonate in popular culture and provoke discussion. As a leading figure of Regionalism, he played a crucial role in the search for a distinctly American artistic identity during a pivotal period in the nation's history. His unique style, merging meticulous Old Master techniques with Midwestern subjects, offered a compelling vision of America, albeit an often idealized and sometimes subtly questioned one.

His work continues to be analyzed for its technical brilliance, its complex thematic content, and its reflection of the cultural anxieties and aspirations of its time. While the initial wave of Regionalism faded, Wood's art endures, prompting ongoing debates about American values, the nature of rural identity, and the relationship between art, myth, and national consciousness. Grant Wood remains a vital figure, not just as a painter of Iowa, but as a chronicler of the complexities of the American experience itself. His art invites us to look closely, not only at the rolling hills and stern faces he depicted, but also at the deeper currents of history, culture, and identity flowing beneath the surface.