Maynard Dixon stands as a pivotal figure in the art of the American West, a painter, illustrator, and muralist whose work captured the vastness, solitude, and spirit of the region with a distinctly modern sensibility. Born Henry St. John Dixon in Fresno, California, on January 24, 1875, he later adopted the name Maynard. His life and art were inextricably linked to the landscapes and peoples of the West, a subject he pursued with unwavering dedication from his youth until his death in Tucson, Arizona, on November 11, 1946. Dixon's legacy is that of an artist who moved beyond romantic illustration to forge a powerful, personal vision of the West, influencing generations of artists who followed.

Early Life and Artistic Stirrings

Dixon grew up in the San Joaquin Valley, a landscape that likely imprinted itself on his young mind. His childhood was marked by bouts of asthma, which sometimes limited his physical activity but perhaps encouraged introspection and observation. He was largely self-taught as an artist, finding inspiration in the illustrations of Western life he saw in popular magazines. A defining moment came at age 16 when he sent some of his sketches to the renowned Western artist Frederic Remington. Remington responded with encouragement, advising the young Dixon to draw directly from nature and life, advice Dixon took to heart throughout his career.

Despite this early encouragement towards direct observation, Dixon did pursue formal training briefly. He enrolled at the California School of Design in San Francisco (now the San Francisco Art Institute) but stayed only three months. He found the traditional, European-focused curriculum stifling and irrelevant to his desire to depict the American West he knew. This rejection of academic convention set the stage for his independent artistic journey, prioritizing firsthand experience over established formulas.

Leaving school, Dixon committed himself to becoming an artist of the West. In 1900, he moved to San Francisco, a burgeoning cultural center. He quickly found work as an illustrator, securing a position with the San Francisco Morning Call. This period was crucial for honing his skills in composition and narrative, forcing him to capture scenes quickly and effectively. His illustrations often depicted scenes of Western life – cowboys, Native Americans, and the dramatic landscapes that formed their backdrop.

The Illustrator and the Explorer

For the first two decades of his career, illustration provided Dixon's primary income. He became highly successful, contributing to major publications like Harper's Weekly, Scribner's, McClure's, and notably, Sunset Magazine, the voice of the Southern Pacific Railroad, which heavily promoted the West. His illustrations appeared alongside stories by prominent Western writers like Jack London and Mary Austin. This work, while commercial, allowed him to travel extensively throughout the West, gathering the raw material that would fuel his paintings.

Dixon undertook numerous sketching trips, venturing into California's deserts and mountains, Arizona, Nevada, Utah, Oregon, and Montana. He sought authenticity, spending time on ranches, visiting remote Native American communities (particularly Hopi, Navajo, Blackfeet, and Pueblo peoples), and immersing himself in the landscapes he wished to paint. He believed that understanding the West required living in it, not just observing it from afar. These journeys provided him with a deep well of subjects and a profound connection to the land and its inhabitants.

His experiences directly informed his evolving artistic vision. He moved away from the action-packed, often anecdotal style favored by illustrators like Remington and Charles M. Russell, seeking instead to capture the underlying structure, mood, and spiritual essence of the Western environment. He became increasingly interested in the formal qualities of painting – composition, color, and light – and began to see illustration as a means to an end, the end being the creation of serious, expressive fine art.

Embracing Modernism

Dixon's artistic development coincided with the rise of Modernism in America. While geographically removed from the East Coast centers where European avant-garde art first made its impact (like the 1913 Armory Show in New York), Dixon was not immune to these currents. San Francisco had its own progressive art scene, and Dixon associated with artists like Xavier Martinez and Gottardo Piazzoni, who were exploring more modern approaches. He absorbed influences from Post-Impressionism, particularly the structural concerns of Paul Cézanne and the expressive color of Paul Gauguin, and later, elements of Cubism.

This shift is evident in his paintings from the 1910s and 1920s. His compositions became bolder and more simplified. He emphasized strong geometric forms, flattened planes, and dramatic arrangements of light and shadow. His color palettes often moved beyond strict naturalism, using color to convey emotion and enhance the design. He developed a characteristic style featuring low horizons, vast, cloud-filled skies, and monumental, simplified landforms, often mesas, buttes, and canyons. This approach aimed to convey the immense scale and profound silence of the Western landscape.

Works like Cloud World and Remembrance of Tusayan Number 2 (also known as Recall of Tuftsianas No. 2) exemplify this modernist leaning. They feature stylized clouds, simplified geological structures, and a focus on pattern and design that goes beyond mere representation. Dixon wasn't interested in photographic accuracy; he sought to distill the essence of the scene, its emotional weight, and its underlying abstract beauty. His approach was often described by his personal motto: "The purpose of painting is the presentation of lasting values."

The Landscape as Soul

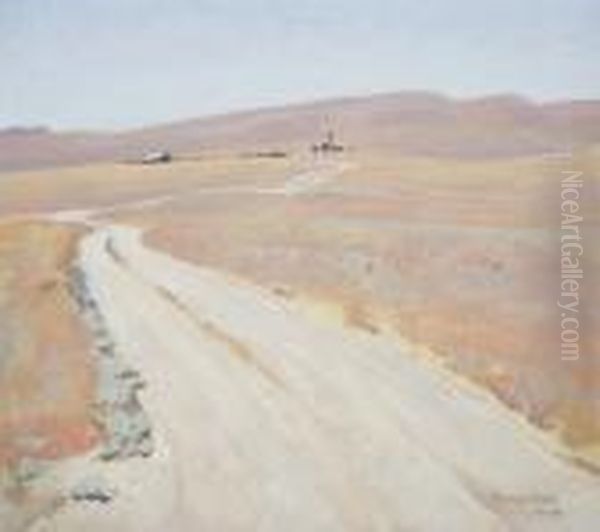

The landscape was arguably Dixon's most profound and enduring subject. He saw the deserts and mountains of the West not just as scenery but as powerful entities possessing a unique spirit and character. His paintings often evoke a sense of timelessness, solitude, and the immense power of nature. He excelled at capturing the quality of light unique to the arid West – the sharp clarity, the intense contrasts, and the subtle atmospheric effects.

His compositions frequently emphasize horizontality, reflecting the vast, open spaces of the region. He often placed small figures, or no figures at all, within these expansive settings, highlighting the relationship between humanity and the overwhelming scale of the natural world. Works like Abandoned Ranch convey a sense of human transience against the enduring backdrop of the land. The low horizon lines draw the viewer's eye upwards into dramatic skies, which Dixon rendered with great skill and variety, from serene blue expanses to turbulent, sculptural cloud formations.

Dixon's travels were essential to this focus. He spent significant time in Arizona, particularly around Tucson and Phoenix, and was deeply drawn to the landscapes of Utah, especially the area near Mount Carmel, and Nevada. The unique geology and light of these places became central motifs in his work. Unlike the earlier Hudson River School painters like Albert Bierstadt or Thomas Moran, who often emphasized the sublime and picturesque aspects of the West, Dixon presented a more austere, sometimes stark, but deeply felt vision. His contemporary in the Southwest, Georgia O'Keeffe, shared a similar interest in abstracting the forms of the desert landscape, though their styles remained distinct.

Depicting the Human Element

While renowned for his landscapes, Dixon also dedicated much of his art to depicting the people of the West. His portrayals of Native Americans stand out for their dignity and lack of romantic sentimentality. Having spent considerable time in various tribal communities, he sought to represent individuals connected to their ancestral lands, often shown in quiet contemplation or integrated harmoniously with the landscape. He aimed to move beyond the stereotypes prevalent in much Western art of the time, presenting figures imbued with presence and resilience. Works like Earth Knower capture this sense of deep connection between the individual and the environment.

He also painted cowboys and settlers, but often focused on the solitary figure or the quiet moments of life, rather than the dramatic action scenes favored by Remington or the nostalgic camaraderie often seen in the work of Charles M. Russell. Dixon and Russell, despite stylistic differences, shared a deep respect for the West and developed a friendship, even sketching together in Montana. Dixon's figures, whether Native American or Anglo, often seem shaped by the vast, demanding environment they inhabit.

His interest in the human condition took a more pointed turn during the Great Depression of the 1930s. Influenced partly by the social consciousness of his then-wife, the photographer Dorothea Lange, Dixon created a powerful series of paintings addressing the economic hardship and social unrest of the era.

Marriage, Influence, and Social Conscience

Dixon's personal life significantly intersected with his artistic career. His first marriage, to artist Lillian West, ended in divorce around 1917, reportedly due to her struggles with alcoholism. In March 1920, he married Dorothea Lange, who was already establishing herself as a portrait photographer in San Francisco. Their marriage lasted fifteen years and produced two sons, Daniel and John. This period was artistically fertile for both. Lange's photographic eye may have influenced Dixon's sense of composition and his focus on capturing essential forms.

The onset of the Great Depression profoundly affected both artists. Lange would go on to create iconic images of Dust Bowl migrants and the rural poor for the Farm Security Administration (FSA). Dixon, sharing her concern for the plight of ordinary people, turned his attention to social realist themes. He created stark, powerful images like Forgotten Man, Shapes of Fear, The Laborer, and The Demonstrator, depicting striking workers, displaced individuals, and the pervasive anxiety of the times. These works marked a departure from his more serene landscapes but shared their compositional strength and emotional directness. Artists like Ben Shahn were exploring similar themes on the East Coast.

Despite their shared social concerns and mutual respect, the demands of their separate, intense careers and perhaps differing temperaments led to strain. They divorced in 1935. Lange's subsequent work continued to define documentary photography, while Dixon increasingly sought refuge and inspiration back in the landscapes of the remote West.

The Muralist

Alongside his easel painting and earlier illustration work, Dixon was also a significant muralist. Murals offered him the opportunity to work on a large scale and engage with public audiences. His simplified, powerful style translated well to mural dimensions. He completed several important commissions, often funded through New Deal programs like the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) and later the Treasury Section of Fine Arts.

One of his most notable mural projects was for the Bureau of Indian Affairs offices within the Department of the Interior building in Washington, D.C., completed in the late 1930s. These murals depicted scenes of Native American life with dignity and cultural sensitivity. He also created murals for post offices and other public buildings.

Perhaps his most famous mural cycle was created for the Arizona Biltmore Hotel in Phoenix, Arizona (commissioned in 1929, though sometimes mistakenly placed in San Diego). These large canvases depict desert scenes and Southwestern motifs, perfectly complementing the hotel's architecture (influenced by Frank Lloyd Wright). His third wife, Edith Hamlin, whom he married in 1937, was also a talented muralist, and they sometimes collaborated or worked on related projects. Dixon's mural work connected him to the broader mural movement of the era, which included artists like Thomas Hart Benton and the Mexican muralist Diego Rivera, though Dixon's style remained distinctly his own.

Later Years in Utah

In 1937, Dixon married Edith Hamlin. Seeking distance from the urban art world and a deeper connection to the landscapes he loved most, they established a home and studio in Mount Carmel, Utah, near Zion National Park, in 1939. This southern Utah location provided Dixon with constant inspiration. The dramatic plateaus, deep canyons, and unique light of the region dominate his later work. He built a log cabin studio where he could paint directly from the environment that surrounded him.

His paintings from this period often possess a profound sense of peace and spiritual connection to the land. Works like Bright Morning, Utah capture the crystalline light and majestic forms of the region. He and Hamlin envisioned their Utah home as a place where other artists could visit and work, fostering a creative community rooted in the Western landscape.

Despite his love for Utah, Dixon's health, particularly his asthma and emphysema, worsened. He began spending winters in the warmer, drier climate of Tucson, Arizona. His final years were marked by declining health, and according to some accounts, periods of withdrawal and sadness, possibly exacerbated by the global turmoil of World War II. He reportedly experienced a significant emotional or mental crisis near the end of his life. He passed away in Tucson in 1946.

Artistic Philosophy and Style Revisited

Dixon's art was guided by a consistent philosophy centered on truth to his subject, simplification of form, and the expression of underlying emotional and spiritual values. He famously stated, "My object has always been to get as close to the real nature of the country as possible." This meant rejecting picturesque clichés and seeking the essential character of the land and its people.

His style is characterized by:

Strong Composition: Often utilizing low horizons, dynamic diagonals, and balanced arrangements of mass and space.

Simplified Forms: Reducing landscapes and figures to their essential geometric structures, influenced by Post-Impressionism and Cubism.

Emphasis on Light and Shadow: Using dramatic contrasts to define form and create mood.

Expressive Color: Employing color palettes that ranged from subtle and harmonious to bold and symbolic.

Monumentality: Conveying the vast scale and enduring presence of the Western landscape.

Emotional Resonance: Imbuing his scenes with feelings of solitude, peace, power, or, in his social realist work, anxiety and resilience.

He stood apart from many of his contemporaries. While respecting the narrative skills of Remington and Russell, his focus shifted towards formal concerns and mood. Unlike the Taos Society of Artists (members like Joseph Henry Sharp, E. Irving Couse, Oscar Berninghaus), who often focused on colorful depictions of Pueblo life, Dixon maintained a more independent, modernist path, though he shared their interest in Native American subjects. His work offers a bridge between traditional Western representation and 20th-century modernism.

Legacy and Historical Evaluation

Maynard Dixon is widely regarded as one of the most important artists of the American West in the 20th century. His unique vision, which combined direct observation with modernist principles, created a powerful and enduring portrayal of the region. He successfully moved beyond illustration to create a significant body of fine art that captured the physical and spiritual essence of the West.

His work is held in major museum collections across the United States, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum (formerly the National Museum of American Art), the Autry Museum of the American West, the Phoenix Art Museum, the Brigham Young University Museum of Art (which holds a significant collection), and the University of Utah Museum of Fine Arts. His home and studio in Mount Carmel, Utah, are preserved and operated by the Thunderbird Foundation for the Arts, continuing his legacy.

Numerous exhibitions have celebrated his work, including major retrospectives that have solidified his reputation. The 2019 exhibition "Wilderness and Solitude: Maynard Dixon in Nevada" at the Nevada Museum of Art and the 2024 show "Space, Silence, Spirit: Maynard Dixon’s West" at the Museum of Northern Arizona attest to the ongoing interest in his art. Critics and historians recognize his ability to convey the unique character of the Western landscape – its vastness, its silence, its harsh beauty, and its spiritual depth – through a distinctive and modern artistic language.

His influence extends to subsequent generations of artists drawn to the Western landscape. His commitment to authenticity, his bold compositions, and his ability to evoke mood continue to inspire. He remains a key figure for understanding the evolution of American art in the first half of the 20th century and the complex ways artists have interpreted the iconic landscapes of the American West.

Conclusion

Maynard Dixon's life was a journey into the heart of the American West, a journey reflected in an artistic output of remarkable consistency and power. From his early days as a self-taught illustrator inspired by Remington to his mature phase as a modernist painter deeply connected to the deserts of Arizona and Utah, he sought to capture the "lasting values" of the land and its people. Through simplified forms, evocative light, and masterful compositions, he conveyed the solitude, grandeur, and spirit of a region undergoing profound change. His marriage to Dorothea Lange brought a period of intense social awareness, while his later years with Edith Hamlin solidified his connection to the Utah landscape he loved. More than just a "Western artist," Dixon was a significant American modernist who chose the West as his subject, leaving behind a body of work that continues to resonate with its unique blend of observation, abstraction, and emotional depth. His ashes were scattered, according to his wishes, on the hillside above his Mount Carmel home, forever linking the artist to the landscape that defined his life and art.