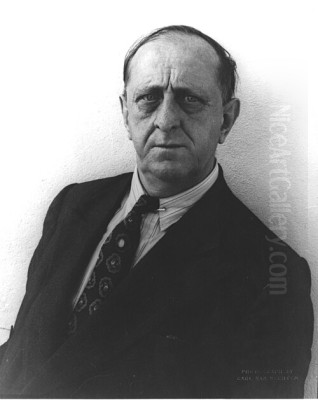

Marsden Hartley stands as one of the most compelling and complex figures in the narrative of American Modernism. A painter, poet, and essayist, his life (1877-1943) was marked by restless travel, profound personal experiences, and an unwavering commitment to forging a unique artistic identity. He navigated the currents of European avant-garde movements, absorbing influences from Cubism and Expressionism, yet ultimately sought to ground his art in an authentic American, particularly New England, sensibility. His work, characterized by bold forms, expressive color, and deep emotional resonance, reflects a lifelong quest for spiritual and artistic belonging.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born Edmund Hartley in Lewiston, Maine, in 1877 to English immigrant parents, his early life was shadowed by instability and loss. The death of his mother when he was only eight, followed by his father's remarriage and the family's relocation, left the young Hartley feeling isolated and adrift. This sense of rootlessness and a yearning for connection would echo throughout his life and art. Maine's rugged landscapes, however, imprinted themselves deeply on his consciousness, becoming a recurring source of inspiration he would return to repeatedly in his later years.

His artistic inclinations emerged early. After the family moved to Ohio, Hartley began his formal art studies, first receiving private lessons in 1896 and then attending the Cleveland School of Art. Seeking broader horizons, he moved to New York City in 1899. There, he enrolled in the New York School of Art, studying under the prominent American Impressionist William Merritt Chase. He also briefly attended the National Academy of Design, benefiting from a scholarship. During these formative years, he absorbed the prevailing academic and Impressionist styles but soon felt drawn to more expressive modes.

A pivotal early influence was the visionary American painter Albert Pinkham Ryder, whose dark, moody, and heavily impastoed canvases resonated with Hartley's own introspective temperament. Hartley admired Ryder's mystical approach to landscape and his independence from mainstream trends. This affinity for the spiritual and the deeply personal in art would remain a constant in Hartley's own development. Early works from this period, such as the Impressionist-inflected Winter's Chaos (1909) or the Pointillist-influenced mountain scene Hall of the Mountain King (1909), show his technical facility and his exploration of contemporary styles while hinting at the bolder directions his art would soon take.

The European Crucible: Paris and Berlin

Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, Hartley recognized the necessity of experiencing European modern art firsthand. Financial support from the influential photographer and gallerist Alfred Stieglitz, who became a crucial early champion, enabled Hartley's first trip abroad in 1912. Paris was his initial destination, a city then electric with artistic innovation. He immersed himself in the avant-garde scene, frequenting the salon of Gertrude Stein and encountering the revolutionary works of Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Henri Matisse, and Paul Cézanne.

The structural logic and fragmented forms of Cubism, particularly the work of Picasso and Braque, profoundly impacted Hartley. He began experimenting with Cubist principles, breaking down objects into geometric planes, although his interpretation often retained a more decorative and symbolic quality than that of his French counterparts. Cézanne's emphasis on underlying structure and his methodical brushwork also proved deeply influential, providing a model for rendering form with solidity and weight.

However, it was Hartley's move to Berlin in 1913 that arguably marked the most intense and transformative period of his European sojourn. Germany, particularly Berlin and Munich, was a center for Expressionism, a movement characterized by subjective emotion, bold color, and distorted forms. Hartley found a powerful affinity with the spiritual intensity and emotional directness of German Expressionist artists like Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, key figures in the Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) group. He exhibited alongside them and absorbed their ideas about art's capacity to convey inner spiritual states.

Berlin's vibrant, militaristic atmosphere before World War I also captivated Hartley. He was fascinated by the pageantry, the uniforms, and the sense of order, which contrasted sharply with his own often-unsettled existence. This environment, combined with his immersion in Expressionism and his ongoing assimilation of Cubism, led to a remarkable synthesis in his work.

The War Years and Personal Tragedy

Hartley's time in Berlin coincided with the lead-up to and outbreak of World War I. This period yielded some of his most celebrated and symbolically rich paintings. He developed a unique abstract style, often referred to as "Kubic-Expressionism," blending Cubist structure with Expressionist color and emotional intensity. His subjects often drew on military symbols – flags, banners, medals like the Iron Cross, epaulets, and numbers – arranged in dynamic, heraldic compositions.

Among the most powerful works from this era is the Portrait of a German Officer (1914), now housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This painting is not a traditional likeness but an abstract composite portrait, believed to memorialize Karl von Freyburg, a Prussian lieutenant with whom Hartley had formed a deep emotional attachment and who was killed early in the war. The canvas is filled with symbols associated with von Freyburg: his initials ("Kv.F."), his age (24), his regiment number (4), and various military insignia. It is a vibrant, coded elegy, expressing both admiration for the perceived masculine ideal embodied by the officer and profound grief over his loss.

Other works in his Berlin Abstraction or "War Motif" series (1914-1915) similarly employ this symbolic language. They are complex arrangements of shapes and colors that convey the energy, tension, and underlying tragedy of the era. While visually dazzling, these paintings carried significant personal weight for Hartley, reflecting his complex feelings about Germany, masculinity, and the devastating reality of war.

His open admiration for Germany and his use of German military symbols, however, proved problematic upon his return to the United States in late 1915, as anti-German sentiment intensified. The perceived "Germanic" nature of his recent work led to criticism and suspicion, hindering his career prospects for a time. This experience underscored the challenges Hartley faced as an artist whose personal experiences and aesthetic choices often ran counter to prevailing nationalistic moods.

Return to America and Shifting Styles

Forced back to America by the war, Hartley struggled to find his footing. The vibrant Berlin art scene was replaced by a different atmosphere in New York. While he reconnected with Alfred Stieglitz and his circle – which included groundbreaking artists like Georgia O'Keeffe, John Marin, Arthur Dove, and Charles Demuth – Hartley felt a degree of alienation. His European experiences had set him apart, and the initial reception of his German paintings was cool.

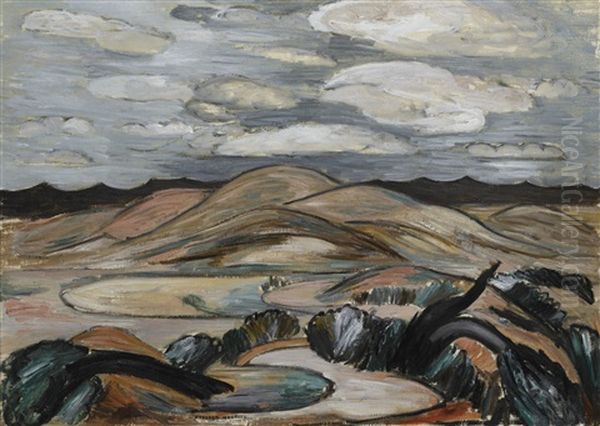

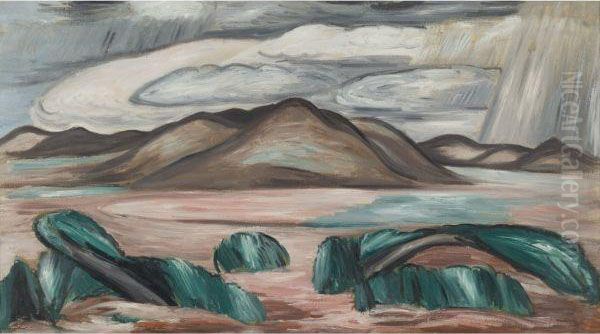

Seeking new environments and inspiration, Hartley embarked on a period of extensive travel within North America. He spent time in Provincetown, Massachusetts, and then journeyed to the American Southwest, living in Taos and Santa Fe, New Mexico, from 1918 to 1919. The stark desert landscapes, vibrant indigenous cultures, and intense quality of light offered a dramatic contrast to both Maine and Europe. His New Mexico paintings often feature simplified, powerful forms and a brighter, earthier palette, reflecting the region's distinct character. He depicted the local landscape and still life arrangements incorporating Native American pottery and textiles.

The 1920s saw Hartley return to Europe, spending time in Paris, Berlin, and Italy. His style continued to evolve, sometimes revisiting abstraction, other times exploring a more representational approach influenced by French modernists like André Derain. He produced landscapes of Provence and still lifes that showed a renewed interest in painterly texture and classical composition. However, this period was also marked by financial instability and a continued sense of searching. A 1925 exhibition of his Recollections series at Stieglitz's gallery received unfavorable reviews, with critics finding fault with the color and composition, highlighting the ongoing difficulty Hartley faced in gaining consistent critical acceptance.

He also briefly engaged with the Dada movement, connecting with artists like Marcel Duchamp, though this influence was less pronounced in his overall oeuvre compared to Cubism or Expressionism. Throughout these years of travel and stylistic exploration, Hartley remained a restless spirit, seeking a place and a mode of expression where his art and his identity could fully coalesce.

A Search for Roots: Maine and Regional Identity

By the early 1930s, Hartley began to feel an increasingly strong pull back to his origins. Encouraged by critics and friends to cultivate a distinctly "American" subject matter, and perhaps driven by his own internal need for grounding, he turned his attention once more to New England. He spent time painting the rugged, granite landscapes around Gloucester, Massachusetts, producing the starkly powerful Dogtown series. These paintings depict a desolate, boulder-strewn common, rendered with a raw energy and simplified forms that convey a sense of primal force and endurance.

His definitive return, however, was to his native Maine. Declaring himself "the painter from Maine," Hartley sought to immerse himself in the state's landscapes, maritime culture, and people. This late phase of his career, from the mid-1930s until his death in 1943, is often considered his most powerful and integrated period. He found inspiration in the state's dramatic coastline, its dense forests, and especially the towering presence of Mount Katahdin, Maine's highest peak.

His late Maine landscapes are characterized by bold outlines, simplified, almost monumental forms, and expressive, often somber colors. Works like Mount Katahdin, Maine (1942) are not merely topographical representations but powerful distillations of the mountain's spiritual and physical presence. He painted the sea with equal force, capturing the relentless energy of the North Atlantic and the hardy lives of the fishermen who worked its waters.

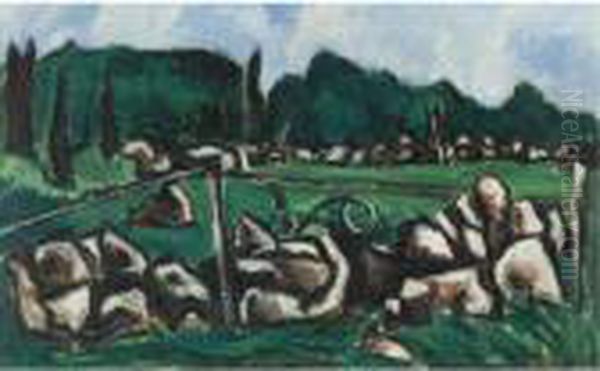

During this period, he also spent time living with a fishing family, the Masons, in Nova Scotia, Canada. This experience deeply affected him, providing a sense of belonging he had long sought. Tragically, the two Mason sons drowned, a loss that resonated with Hartley's earlier grief over Karl von Freyburg. This led to powerful figurative works like Fishermen's Last Supper (1940-41), which memorializes the family with a raw, folk-art-inspired directness and profound empathy. His late portraits of fishermen and loggers possess a similar iconic, rugged quality. These late works solidified Hartley's reputation as a major voice in American regionalism, albeit one infused with modernist sensibilities and deep personal feeling.

Beyond Painting: Hartley the Writer

Marsden Hartley's creative output was not limited to the visual arts. He was also a prolific writer, producing poetry, essays, and art criticism throughout his life. His writing often paralleled the themes and concerns found in his paintings: a deep engagement with nature, a search for spiritual meaning, reflections on art and artists, and explorations of personal identity and place.

His poetry, collected in volumes such as Twenty-five Poems (published 1923), often employed modernist techniques, including fragmented syntax and unconventional imagery. Like his paintings, his poems could range from intimate reflections to broader meditations on the American landscape and spirit. He admired the work of American Transcendentalist writers like Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, as well as the expansive verse of Walt Whitman. Their emphasis on individualism, the spiritual significance of nature, and the search for an authentic American voice resonated deeply with Hartley's own artistic project.

Hartley also wrote extensively about art and artists he admired, including essays on Cézanne, Ryder, and folk art. His critical writings provide valuable insights into his own aesthetic principles and his understanding of modern art history. He championed intuition, emotional expression, and a connection to place as vital components of artistic creation. His dual identity as painter and writer underscores the intellectual depth and multifaceted nature of his engagement with the world. His writings reveal a mind constantly grappling with questions of aesthetics, spirituality, and cultural identity, enriching our understanding of his visual work. His interest in mysticism and Eastern religions, including Buddhism and Hinduism, also occasionally surfaced in his writings, reflecting another dimension of his quest for meaning.

Artistic Influences and Connections

Hartley's artistic journey was shaped by a diverse array of influences and interactions. His early engagement with William Merritt Chase provided a foundation in academic technique, while his admiration for Albert Pinkham Ryder pointed towards a more mystical and personal path. The European avant-garde, however, proved transformative. Paul Cézanne's structural approach to form, the Cubist innovations of Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and the expressive color of Henri Matisse all left indelible marks on his style.

In Germany, the spiritual intensity and bold aesthetics of Wassily Kandinsky and Franz Marc, leading figures of Der Blaue Reiter, were crucial. Hartley absorbed their belief in art's power to express inner necessity and spiritual realities. He also shared affinities with other Expressionists, navigating the vibrant, if fraught, cultural scene of pre-war Berlin.

Back in the United States, Alfred Stieglitz was a pivotal figure, providing not only financial support but also a crucial platform through his '291' gallery and later venues. Hartley was part of Stieglitz's circle, which included major American modernists like Georgia O'Keeffe, John Marin, Arthur Dove, and Charles Demuth. While Hartley maintained his distinct artistic personality, his association with this group placed him at the heart of American modern art's development. He also maintained connections with writers and intellectuals, including Gertrude Stein in Paris and later, figures like Hart Crane and William Carlos Williams in America.

Hartley's own work, in turn, exerted an influence. His bold handling of paint, his expressive use of color, and his powerful engagement with the American landscape resonated with later generations of artists. Figures associated with Abstract Expressionism, such as Milton Avery with his simplified forms and evocative color, and perhaps even Philip Guston in his later, rugged figurative work, show echoes of Hartley's pioneering spirit and his commitment to deeply personal expression rooted in place.

Hartley's Enduring Legacy

Marsden Hartley's path was rarely easy. He faced financial struggles, critical misunderstanding, and the personal challenges of being a gay man in an often intolerant society. His nomadic life, driven by both artistic curiosity and a search for belonging, meant he often felt like an outsider. Critical reception during his lifetime was inconsistent; while recognized by key figures like Stieglitz, he never achieved widespread fame or financial security. His German-themed works faced political backlash, and later stylistic shifts sometimes confused critics seeking a consistent "American" style.

However, since his death in 1943, Hartley's reputation has steadily grown. He is now firmly established as a major figure in American Modernism, recognized for his crucial role in bridging European avant-garde ideas with American subjects and sensibilities. His willingness to experiment across different styles – from Impressionism and Cubism to Expressionism and a powerful late Regionalism – is seen not as inconsistency but as evidence of a restless, searching intellect.

His late Maine paintings, in particular, are celebrated for their raw power, emotional depth, and profound connection to place. They are considered among the most compelling depictions of the New England landscape in American art. His Berlin-period works are acknowledged as a unique and significant contribution to early 20th-century abstraction, notable for their complex symbolism and historical resonance.

Major retrospectives, such as the one organized by the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art and the large-scale European survey at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in 2019, have brought renewed attention to the breadth and depth of his achievements. His life story, marked by both artistic triumphs and personal struggles, continues to fascinate scholars and the public alike. Hartley's legacy lies in his powerful, often deeply personal body of work, his pioneering role in American abstraction, and his enduring quest to create an art that was both modern and deeply rooted in his experience of the world.

Major Works and Where to Find Them

Marsden Hartley's works are held in major museum collections across the United States and internationally. Key institutions where his art can be viewed include:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York: Holds iconic works such as Portrait of a German Officer (1914).

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York: Possesses a significant collection spanning his career, frequently featuring his work in exhibitions on American Modernism.

Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York: Includes important examples of his work, particularly relating to his engagement with modernism and landscape.

National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.: Features major late works like Mount Katahdin, Maine (1942).

Bates College Museum of Art, Lewiston, Maine: Located in his hometown, it holds the Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection, including paintings, drawings, and personal effects.

Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut: Has a strong collection and has organized major retrospectives of his work.

Cleveland Museum of Art: Holds works such as Military (1913), reflecting his Berlin period.

Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.: Features several Hartley paintings, showcasing different phases of his career.

Art Institute of Chicago: Includes notable examples of his oeuvre.

Walker Art Center, Minneapolis: Holds important works, including paintings from his Berlin period.

Key representative works that encapsulate his diverse output include:

Hall of the Mountain King (1909) - Early landscape showing Post-Impressionist influence.

Portrait of a German Officer (1914) - Masterpiece of his Berlin abstract period.

Berlin Abstraction (1914-15) - Emblematic of his "War Motif" series.

Movement, Sails (c. 1916) - Example of his post-Berlin abstraction.

Landscape, New Mexico (1919-1920) - Reflecting his Southwestern period.

Eight Bells' Folly, Memorial for Hart Crane (1933) - Symbolic seascape.

Dogtown series (early 1930s) - Stark Massachusetts landscapes.

Fishermen's Last Supper (1940-41) - Powerful figurative work from his Nova Scotia experience.

Mount Katahdin, Maine (1942) - Iconic late landscape painting.

Madawaska - Acadian Light-Heavy (1940) - Example of his late, rugged portraiture.

Conclusion

Marsden Hartley remains a vital and resonant figure in American art history. His life was a testament to the complexities of navigating personal identity, artistic influence, and cultural belonging in a rapidly changing modern world. As a painter, he moved fluidly between abstraction and representation, between European avant-garde styles and a deeply felt American regionalism. As a writer, he articulated the spiritual and aesthetic quests that drove his visual art. From the coded symbolism of his Berlin abstractions to the raw, elemental power of his late Maine landscapes, Hartley forged a unique and enduring artistic language. His work continues to speak to themes of place, loss, spirituality, and the persistent search for authenticity, securing his position as a foundational, if often solitary, pioneer of American Modernism.