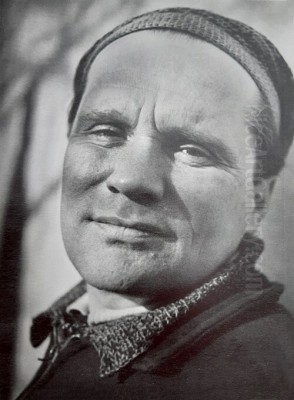

István Dési Huber stands as a significant figure in twentieth-century Hungarian art, an artist whose work navigated the complex currents of European modernism while remaining deeply rooted in the social and political realities of his time. Born István Huber on February 6, 1895, in Nagyenyed, Transylvania (then part of Hungary, now Aiud, Romania), he adopted the name Dési Huber later in his career. His relatively short life, ending prematurely in Budapest in 1944 due to tuberculosis, was marked by personal hardship, dedicated artistic study, and a profound commitment to using art as a means of social commentary. Primarily known as a painter and graphic artist, his oeuvre includes powerful still lifes, expressive landscapes, and poignant depictions of working-class life, all characterized by a distinctive blend of formal experimentation and humanist concern.

Early Life and Formative Experiences

Dési Huber's early years were shaped by instability. His father, a jeweler, faced bankruptcy, plunging the family into financial difficulty. This hardship forced the young István to leave home and wander through nearby villages before eventually making his way to Budapest, the vibrant cultural heart of Hungary. The city offered opportunities for artistic development, though his path was not straightforward. He initially apprenticed as a goldsmith, a trade that provided him with foundational skills in metalworking and engraving – techniques that would later inform his graphic art.

Alongside his apprenticeship, he sought formal art education, studying painting in Budapest. His pursuit of artistic knowledge was interrupted by the outbreak of World War I. Like many young men of his generation, he was conscripted into the Austro-Hungarian army in 1914. The war years undoubtedly exposed him to the harsh realities of conflict and societal upheaval, experiences that likely deepened his awareness of social issues and human suffering, themes that would resonate throughout his later work.

Post-War Studies and Artistic Development

Returning to Budapest after the war's end in 1918, Dési Huber resumed his artistic pursuits with renewed determination. The post-war period was a time of political turmoil and cultural ferment in Hungary, witnessing the brief Hungarian Soviet Republic followed by a conservative counter-revolution. Amidst this charged atmosphere, Dési Huber continued his studies, focusing particularly on graphic techniques. He honed his skills in copperplate engraving at a private art school, reportedly run by the respected graphic artist Artúr Podolini-Volkmann. This technical mastery would become a crucial aspect of his artistic identity.

Seeking broader horizons, Dési Huber moved to Vienna in 1921. There, he studied painting under Otto Prowe, further expanding his artistic vocabulary. Vienna, still a major cultural center despite the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, exposed him to different artistic currents. His time abroad also included a period in Milan, Italy, where he continued to refine his engraving techniques. This period of travel and study broadened his perspective and technical abilities, preparing him for his mature artistic career back in Hungary.

Around 1927-1928, he married Stefánia Sugár, herself an artist and the sister of the painter Andor Sugár. This union brought him into closer contact with other artists. He is known to have exhibited alongside his brother-in-law, Andor Sugár, indicating his growing integration into the Budapest art scene upon his return. These personal and professional connections provided support and stimulus as he began to forge his unique artistic path.

The Emergence of a Distinctive Style: Cubism and Expressionism

By the late 1920s and early 1930s, Dési Huber had developed a distinctive artistic style that synthesized influences from major European modernist movements, particularly Cubism and Expressionism, adapting them to his own thematic concerns. The analytical approach of Cubism, pioneered by artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, is evident in Dési Huber's tendency to break down objects and figures into geometric planes and reassemble them, exploring structure and form beyond superficial appearances.

However, his work rarely embraced the purely formal or abstract concerns sometimes associated with Cubism. Instead, he infused his structured compositions with an emotional intensity and social awareness characteristic of Expressionism. The heightened color, distorted forms, and focus on subjective experience found in the work of German Expressionists like Käthe Kollwitz or George Grosz, or even earlier figures like Edvard Munch, find echoes in Dési Huber's depictions of poverty, labor, and urban life. He sought an art that was formally rigorous yet emotionally resonant and socially relevant.

This synthesis allowed him to create images that were both modern in their formal language and deeply engaged with the human condition. He rejected what he perceived as the decorative superficiality of some contemporary art, striving instead for a style that could convey the weight and gravity of his subjects. His paintings and prints from this period often feature strong outlines, simplified forms, and a somber palette, contributing to their powerful, often unsettling, impact.

The Still Life as a Vehicle for Meaning

While Dési Huber worked across genres, his contribution to the still life (csendélet in Hungarian) is particularly noteworthy. Traditionally considered a lower genre in the academic hierarchy, still life painting underwent a significant re-evaluation in modern art, becoming a key site for formal experimentation for artists from Jean-Baptiste-Siméon Chardin to Paul Cézanne and the Cubists. Dési Huber embraced the genre, transforming it into a potent vehicle for symbolic meaning and social commentary.

His still lifes are far from mere arrangements of inanimate objects. Instead, they are carefully constructed compositions where everyday items – books, tools, plants, personal belongings – are imbued with deeper significance. He explored what the provided text refers to as "verisimilitude," not in the sense of photographic realism, but in conveying the essential truth or reality of the objects and their interconnections, often creating symbolic narratives within the frame.

A prime example is his Still Life with Liebknecht Print (Csendélet Liebknecht-nyomattal), dating from around 1930. This work features a collection of objects, including what appears to be a print referencing Karl Liebknecht, the German socialist leader murdered in 1919. The inclusion of such a politically charged image within a domestic setting immediately signals the artist's socio-political engagement. Other elements mentioned in analyses, such as symbolic representations of a bride, a cypress tree, or a red cigarette, further contribute to a complex layering of personal and political meaning, speaking to themes of commitment, ideology, and perhaps loss or remembrance.

Another significant work, Still-Life with Bauhaus Book (Csendélet Bauhaus-könyvvel, c. 1930), similarly uses objects to create a dialogue about art, ideology, and modernity. The inclusion of a Bauhaus publication points to contemporary debates about functionalism, design, and the role of art in society – themes central to Dési Huber's own thinking. These works demonstrate his ability to elevate the still life genre, using it not just for formal exploration but as a platform for intellectual and social discourse, connecting the private sphere of objects with the public sphere of ideas and politics.

Social Consciousness and Political Engagement

István Dési Huber was not an artist confined to his studio; he was an active participant in the intellectual and political life of his time. He was deeply involved in the Hungarian left-wing intellectual movement, a milieu that included writers, artists, and thinkers critical of the conservative Horthy regime that governed Hungary during the interwar period. His commitment went beyond mere sympathy; he actively contributed through his writings and his art.

He authored articles discussing the role of art in society, arguing for an art that engaged with contemporary realities and served the cause of social progress. He was critical of art that retreated into formalism or aestheticism, detached from the struggles of ordinary people. His own work consistently reflected this conviction, focusing on themes of labor, poverty, social injustice, and the lives of the urban proletariat. His depictions of workers, often rendered with a stark, monumental quality, convey both hardship and dignity.

His engagement led him to associate with organized groups of like-minded artists. He was connected with the KÚT (Képzőművészek Új Társasága – New Society of Artists), a significant association that brought together various strands of modern Hungarian art, including artists like the expressive landscape painter József Egry and former members of the influential avant-garde group 'The Eight' (Nyolcak) such as Róbert Berény. Later, and perhaps more centrally to his identity, he became a leading figure in the Socialist Artists' Group (Szocialista Képzőművészek Csoportja), founded in 1934. This group explicitly aimed to create art aligned with socialist ideals, focusing on realistic depictions of working-class life and social critique. His involvement placed him alongside other socially committed Hungarian artists, such as Gyula Derkovits, whose powerful depictions of the marginalized also combined modernist form with social commentary.

Dési Huber's political stance and socially conscious art put him at odds with the prevailing cultural politics of the Horthy era, which favored more traditionalist and nationalist themes. Despite this, he persisted in creating work that spoke truth to power, using his art as a tool for awareness and advocacy.

Artistic Techniques: Painting and Printmaking

Dési Huber's technical proficiency was integral to his artistic expression. His training as both a painter and an engraver equipped him with a versatile set of skills. In his paintings, he often employed oil on canvas or board, using strong brushwork and a deliberate application of color. His palette, while capable of vibrancy, often leaned towards more somber tones – earth colors, deep blues, grays, and blacks – punctuated by strategic use of brighter hues for emphasis. The influence of Cubism is visible in the faceting of forms and the structured composition, while Expressionist tendencies emerge in the sometimes-raw energy of the brushstrokes and the emotional weight conveyed.

His mastery of graphic arts, particularly copperplate engraving and etching, was equally important. Printmaking allowed for wider dissemination of his images and suited the stark, linear quality often desired for social commentary. Figures like Käthe Kollwitz had demonstrated the power of printmaking for social critique, and Dési Huber embraced the medium with similar conviction. His prints often possess a graphic power and clarity that complements his painted work. The precise lines and tonal contrasts achievable through engraving allowed him to create images of striking intensity and detail, whether depicting urban landscapes, portraits, or symbolic still lifes. His early training as a goldsmith likely contributed to his meticulous approach to the engraving process.

Associations and Artistic Circles

Throughout his career, Dési Huber interacted with a network of artists, intellectuals, and institutions that shaped his development and reception. His teachers, Artúr Podolini-Volkmann in Budapest and Otto Prowe in Vienna, provided crucial technical and artistic grounding. His marriage to the artist Stefánia Sugár and his collaboration with her brother, Andor Sugár, placed him within a supportive artistic family.

His involvement with KÚT connected him to a broader circle of Hungarian modernists exploring various styles, from Expressionism to Post-Impressionism and Constructivist tendencies. While KÚT was diverse, it represented a progressive force in Hungarian art. His later leadership role in the Socialist Artists' Group solidified his position within the politically engaged wing of the Hungarian art scene. This group provided a platform for artists committed to social realism and critique, distinguishing them from artists favored by the establishment, such as the more decorative Vilmos Aba-Novák or the lyrical István Szőnyi, who represented different facets of interwar Hungarian art.

He also engaged with contemporary European art movements through publications and exhibitions. His Still-Life with Bauhaus Book indicates an awareness of and engagement with international currents like the Bauhaus movement, even if his own style differed significantly from the functionalist aesthetic often associated with it. He was also aware of socially critical art elsewhere in Europe, drawing parallels with artists like Kollwitz and Grosz in Germany.

Exhibitions, Collections, and Recognition

Despite the challenges posed by his political leanings and the difficult economic climate of the interwar years, Dési Huber achieved recognition during his lifetime and has been celebrated posthumously. His works were exhibited in Budapest, including shows potentially linked to the Haas Gallery (though the provided source confusingly gives a Salzburg address for a gallery associated with Budapest curators János Haas, Anna Kopoczy, and Ferencs Závada, suggesting a Budapest connection is more likely for Dési Huber's work) and the Budapest Gallery of Contemporary Art (Budapest Galéria, located at Lajos utca 158, which held an exhibition featuring his work as recently as 2015).

His paintings and prints entered important public collections. The Hungarian National Gallery (Magyar Nemzeti Galéria) in Budapest holds a significant collection of his works, solidifying his place in the canon of Hungarian art. Works may also be found in other Hungarian institutions, potentially including university collections like those associated with ELTE University, located near the Hungarian National Museum on Múzeum körút (the address mentioned as "Múzeum Egyetemi" in the source).

Posthumous exhibitions and publications have continued to explore his legacy. The 2007 exhibition and accompanying publication associated with Haas Gallery, focusing on works like Still Life with Liebeskind Print, attest to ongoing scholarly and curatorial interest. His work is studied as a key example of Hungarian modernism that successfully integrated avant-garde formal language with profound social engagement.

Later Life, Illness, and Legacy

István Dési Huber's promising career was tragically cut short. He suffered from tuberculosis, a disease that plagued many in the era, particularly those living in difficult conditions. Despite his illness, he continued to work, producing powerful images even in his final years. He died in Budapest on February 25, 1944, at the age of 49, during the tumultuous final years of World War II in Hungary.

His legacy, however, endured. He is remembered as one of the most important Hungarian artists of the interwar period, a painter and graphic artist who forged a unique path between aesthetic innovation and social responsibility. His work stands as a testament to the power of art to reflect, critique, and engage with the complexities of modern life. He demonstrated that modernist formal languages like Cubism and Expressionism could be effectively employed not just for aesthetic exploration but also to convey deep human empathy and sharp social commentary.

His influence can be seen in subsequent generations of Hungarian artists who grappled with questions of realism, social engagement, and the role of the artist in society, particularly in the post-war era. Figures like Sándor Bortnyik, though an earlier avant-garde figure who later adapted to socialist realism, represent the ongoing dialogue about art and ideology that Dési Huber participated in. Dési Huber's commitment to depicting the lives of ordinary people and his fusion of modern form with humanist content continue to resonate, securing his position as a crucial figure in the narrative of 20th-century Hungarian art history.

Conclusion: A Bridge Between Art and Society

István Dési Huber occupies a vital place in Hungarian art history as an artist who successfully bridged the gap between formal modernist experimentation and deep social consciousness. In a period marked by political tension and social inequality, he chose not to retreat into purely aesthetic concerns but to use his considerable artistic talents to engage with the world around him. His powerful still lifes, expressive depictions of labor, and poignant graphic works remain compelling examples of art that is both formally sophisticated and profoundly human. By synthesizing influences from Cubism and Expressionism and infusing them with his own experiences and convictions, he created a body of work that continues to speak to the enduring relationship between art, society, and the human condition. His life and art serve as a powerful reminder of the artist's potential role as both an innovator and a social commentator.