Henricus "Han" Antonius van Meegeren, a name that resonates with infamy and a peculiar brand of genius in the annals of art history, remains one of the most intriguing figures of the 20th century. Born on October 10, 1889, in the quaint Dutch town of Deventer, and passing away on December 30, 1947, in Amsterdam, Van Meegeren's life was a complex tapestry of artistic ambition, critical rejection, audacious deception, and ultimately, a bizarre form of national heroism. He was a painter whose original works were largely dismissed by critics, yet whose forgeries of Old Masters, particularly Johannes Vermeer, duped the most esteemed experts, collectors, and even the Nazi elite. His story is not merely one of criminal enterprise but a fascinating exploration of art authentication, the psychology of experts, and the very nature of artistic value.

Early Life and Artistic Stirrings

Han van Meegeren's childhood was marked by a burgeoning artistic talent that clashed with the stern, unyielding disapproval of his father, Henricus Wilhelmus van Meegeren, a history teacher and a man of rigid principles. The elder Van Meegeren viewed art as a frivolous pursuit and actively discouraged his son's creative inclinations, sometimes resorting to tearing up Han's drawings and admonishing him for his "unmanly" interests. This paternal opposition, however, seemed only to fuel young Han's determination.

A crucial figure in Van Meegeren's early artistic development was his art teacher at the Hogere Burger School in Deventer, Bartus Korteling. Korteling, himself an artist, recognized Van Meegeren's innate ability and became a mentor. He instilled in his student a deep appreciation for the techniques of the Dutch Golden Age painters, particularly Johannes Vermeer. Korteling emphasized the importance of traditional methods, the careful grinding of pigments, and the meticulous application of paint, lessons that Van Meegeren would later exploit with astonishing success. Under Korteling's guidance, Van Meegeren learned to revere masters like Vermeer and Frans Hals, whose luminous works and technical brilliance became his obsession.

Despite his father's wishes for him to pursue a more "respectable" career in architecture, Van Meegeren enrolled at the Delft University of Technology in 1907. While ostensibly studying architecture, he continued to nurture his passion for painting, even winning a prestigious gold medal for a drawing in the style of the 17th century from the university. This early success perhaps solidified his belief in his own artistic capabilities, particularly in emulating the classical styles.

The Aspiring Artist and Critical Disdain

After marrying his first wife, Anna de Voogt, in 1912, Van Meegeren dedicated himself more fully to painting. He moved to The Hague and began to establish himself as a portraitist and commercial artist. His early original works, often depicting biblical scenes or romanticized subjects in a somewhat traditional, if uninspired, style, achieved a degree of popular success. He was a skilled draftsman and had a good sense of color, which brought him commissions and a comfortable living.

However, the critical art world of the early 20th century, increasingly dominated by modernist movements like Cubism, Fauvism, and Surrealism, championed by artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, and Salvador Dalí, found Van Meegeren's work to be derivative and anachronistic. Critics dismissed his paintings as lacking originality and vision, essentially branding him a competent but ultimately uninspired technician clinging to outdated aesthetics. This constant barrage of negative criticism deeply wounded Van Meegeren's pride and fostered a simmering resentment towards the art establishment.

He felt that his talent was unjustly overlooked and that the critics, in their adulation of modern art, had lost their ability to appreciate true craftsmanship. This bitterness, coupled with a desire for both financial gain and a spectacular form of revenge, began to steer him down a path that would secure his place in history, albeit not in the way he might have initially envisioned. He decided that if the critics could not appreciate his own art, he would prove their fallibility by creating works they would hail as masterpieces, but under the guise of a revered Old Master.

The Genesis of Deception: Mastering the Masters

Van Meegeren's plan was audacious: to forge paintings by 17th-century Dutch Golden Age masters, particularly Johannes Vermeer, whose known oeuvre was relatively small, making the "discovery" of a new work a sensational event. He meticulously researched the materials and techniques of the period. He learned to grind his own pigments using traditional methods, avoiding anachronistic modern chemicals. He sourced old canvases from the 17th century, often scraping off existing, less valuable paintings to reuse them.

One of his most ingenious innovations was the use of phenolformaldehyde resin, a type of Bakelite, mixed with his oil paints. When baked in an oven, this mixture would harden the paint rapidly, creating the convincing craquelure (network of fine cracks) characteristic of centuries-old paintings. He would then roll the canvas over a cylinder to further enhance the cracking and fill the cracks with India ink to simulate the accumulated dirt of ages. He also studied the lives and supposed stylistic developments of the artists he intended to forge, aiming to create works that could plausibly fit into their known body of work or represent a "lost" period.

His early forgeries included works in the style of Frans Hals, Pieter de Hooch, and Gerard ter Borch. These served as practice, allowing him to refine his techniques and test the waters of the art market. While some of these early attempts were successful, his ultimate target was Vermeer, the enigmatic Sphinx of Delft, whose paintings were, and remain, among the most prized and valuable in the world.

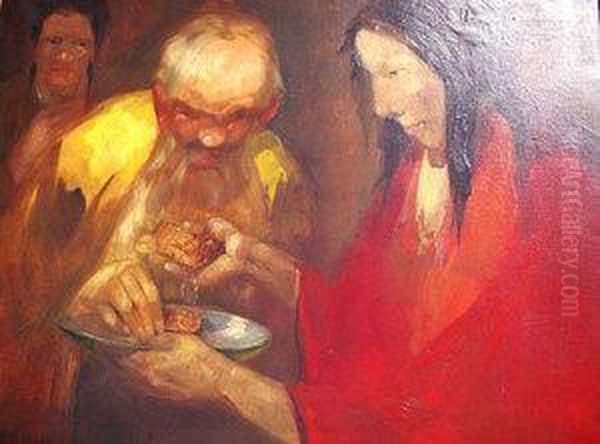

The "Vermeer" Sensation: The Supper at Emmaus

The culmination of Van Meegeren's meticulous preparation came in 1937 with the unveiling of The Supper at Emmaus. He presented this painting as a newly discovered early religious work by Johannes Vermeer. The painting depicted Christ and his disciples in a style that, while recognizably "Vermeer-like" in its lighting and composition, also incorporated elements reminiscent of Italian masters like Caravaggio, whom Vermeer might have been influenced by.

The painting was submitted to Dr. Abraham Bredius, one ofthe most respected art historians and Vermeer experts of the time. Bredius, then in his eighties, was captivated. He had long theorized about a possible early religious phase in Vermeer's career, influenced by Italian art, and The Supper at Emmaus seemed to be the missing link, the definitive proof of his theory. In a glowing article for The Burlington Magazine in November 1937, Bredius declared it "the masterpiece of Johannes Vermeer of Delft," praising its "sublime" and "touching" qualities.

Bredius's enthusiastic endorsement was all Van Meegeren needed. The art world was electrified. The Boymans Museum in Rotterdam (now Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen) purchased The Supper at Emmaus for a substantial sum (520,000 Dutch guilders, equivalent to several million dollars today), with significant contributions from private collectors and foundations. Van Meegeren had not only fooled the experts but had also seen his creation celebrated as a national treasure. The financial rewards were immense, but perhaps more satisfying for Van Meegeren was the validation, albeit under false pretenses, and the humiliation of the critics he so despised.

A Prolific Forger: The "Lost Vermeers" Emerge

Buoyed by the triumph of The Supper at Emmaus, Van Meegeren embarked on a prolific period of Vermeer forgeries. He created at least six more "Vermeers," including Isaac Blessing Jacob, Christ and the Adulteress, The Washing of the Feet, Woman Reading Music, and Woman Playing Music. These paintings were carefully crafted to fit the narrative of Vermeer's supposed early religious period or to fill other perceived gaps in his oeuvre.

Each new "discovery" was met with varying degrees of excitement and acceptance, largely due to the lingering authority of Bredius's initial pronouncements. Collectors and dealers, eager to acquire a rare Vermeer, were often willing to overlook inconsistencies or stylistic oddities. Van Meegeren became wealthy, acquiring a lavish estate and living extravagantly. He cleverly managed the sales of his forgeries through intermediaries, further obscuring his involvement.

His technique continued to evolve. He used badger hair brushes, similar to those Vermeer might have used, and developed methods to make his canvases appear authentically aged. He understood the psychology of collectors and experts, playing on their desires and expectations. The figures in his "Vermeers" often had heavy eyelids and a somewhat sentimental expression, features that later became tell-tale signs of his hand but were initially interpreted as characteristics of Vermeer's early, more emotive style.

The Nazi Connection: A Forgery for Göring

The outbreak of World War II and the subsequent Nazi occupation of the Netherlands provided Van Meegeren with new, albeit dangerous, opportunities. High-ranking Nazi officials were avid art collectors, often plundering works from occupied territories or acquiring them through various means. Hermann Göring, Hitler's second-in-command and head of the Luftwaffe, was particularly notorious for his insatiable appetite for art.

In 1942, one of Van Meegeren's "Vermeers," Christ and the Adulteress, found its way into Göring's vast collection. The painting was sold through an intermediary, and Göring reportedly traded 137 paintings for it, considering it one of the jewels of his collection. Van Meegeren received a huge sum for this transaction, further enriching himself during a time of widespread hardship. This sale, however, would later prove to be a critical turning point in his career.

Selling a Dutch national treasure, especially a work by a revered master like Vermeer, to the enemy was considered an act of collaboration and treason. While Van Meegeren was profiting, he was also unknowingly setting the stage for his eventual downfall. Other Dutch masters whose works were highly sought after by the Nazis included Rembrandt van Rijn, Jan Steen, and Jacob van Ruisdael, highlighting the cultural significance of the art Göring and others were amassing.

The Post-War Reckoning: From Collaborator to Confessor

After the liberation of the Netherlands in 1945, Allied authorities began the arduous task of recovering looted art and prosecuting collaborators. The trail of Christ and the Adulteress led investigators to Han van Meegeren. In May 1945, he was arrested, not for forgery, but on charges of collaboration with the enemy for selling a Dutch cultural property to Göring. The penalty for treason was severe, potentially even death.

Faced with this dire situation, Van Meegeren made a stunning confession: he had not sold a real Vermeer to Göring; he had sold a fake, one that he himself had painted. He claimed that Christ and the Adulteress, along with The Supper at Emmaus and other "Vermeers" and "Pieter de Hoochs," were all his own creations. His motive, he asserted, was to dupe the art world, particularly the critics who had scorned him, and, in the case of Göring, to swindle a Nazi.

Initially, the authorities and the art world were incredulous. The idea that so many esteemed experts, including the venerable Bredius, had been fooled seemed preposterous. The paintings had been authenticated, celebrated, and purchased for enormous sums. To prove his claim, Van Meegeren, under police guard, agreed to paint another "Vermeer" in his characteristic style. Over a period of several weeks, between July and November 1945, he created his final forgery, Jesus Among the Doctors (also known as Young Christ in the Temple). He used his familiar techniques, including the Bakelite resin, and produced a work that was recognizably in the style of his previous forgeries.

The Trial and Scientific Vindication

Van Meegeren's trial began in October 1947 and became a media sensation. The charges had shifted from collaboration to forgery and fraud. The public, initially viewing him as a traitor, began to see him in a new light: a cunning trickster who had made fools of art critics and, most deliciously, had swindled Hermann Göring, one of the most reviled Nazi leaders. He became a sort of folk hero.

A key element of the trial was the scientific evidence. An international commission of experts, led by Dr. Paul Coremans from Belgium, conducted extensive technical examinations of the disputed paintings. They analyzed pigments, binding media, and the craquelure. Their findings were conclusive: the paintings contained phenolformaldehyde resins (Bakelite), a modern synthetic material that Vermeer could not possibly have used. Specific pigments, like cobalt blue, were found in ways inconsistent with 17th-century practice. The artificial aging techniques were also exposed.

The evidence was irrefutable. Van Meegeren was telling the truth. He had indeed painted the "Vermeers." On November 12, 1947, Han van Meegeren was convicted of forgery and fraud and sentenced to a relatively lenient one year in prison. The collaboration charges were effectively dropped, as he had sold a fake, not a national treasure, to Göring.

However, Van Meegeren would never serve his sentence. His health, already strained by years of alcohol and drug abuse, deteriorated rapidly. On December 30, 1947, just weeks after his conviction, Han van Meegeren died of a heart attack in Amsterdam, at the age of 58.

Legacy: The Forger Who Changed Art History

Han van Meegeren's legacy is complex and multifaceted. He was a criminal who perpetrated one of the most audacious art frauds in history, yet his actions had profound and lasting consequences for the art world.

His forgeries exposed the fallibility of connoisseurship – the reliance on an expert's subjective eye and intuition for authentication. The ease with which he duped renowned scholars like Abraham Bredius sent shockwaves through the art establishment and forced a re-evaluation of authentication methods. While the "eye" of the expert remains important, Van Meegeren's case underscored the critical need for rigorous scientific analysis as a complementary tool. Institutions became more reliant on techniques like X-radiography, infrared reflectography, pigment analysis, and dendrochronology (for panel paintings).

The scandal also raised uncomfortable questions about the nature of artistic value. If a forgery could evoke the same aesthetic pleasure and emotional response as a genuine masterpiece, what did that say about the intrinsic value of art versus the value ascribed by attribution and provenance? Van Meegeren's The Supper at Emmaus, hailed as a sublime work when believed to be a Vermeer, was suddenly demoted to a mere curiosity once revealed as a fake. Yet, the painting itself had not changed.

His story also highlighted the allure of the Dutch Golden Age, a period that produced not only Vermeer and Frans Hals, but also giants like Rembrandt van Rijn, and masters of genre scenes like Pieter de Hooch, Jan Steen, and Gabriel Metsu, as well as landscape artists like Jacob van Ruisdael and still-life painters such as Rachel Ruysch. The scarcity of Vermeer's works, in particular, created a fertile ground for a forger who could convincingly fill the perceived gaps in his oeuvre.

Van Meegeren became a figure of popular fascination, his story adapted into books, plays, and films. He was seen by some as a rebel who exposed the pretentiousness of the art elite, a Dutch folk hero who outsmarted the Nazis. To others, he was simply a gifted but cynical fraudster.

Today, Han van Meegeren's forgeries, particularly The Supper at Emmaus and Christ and the Adulteress, are held in museum collections and are studied as much for their historical significance as for their artistic qualities. They serve as a permanent reminder of a remarkable episode in art history, a testament to one man's talent for deception and the enduring challenge of distinguishing the authentic from the imitation. His life, a blend of artistic skill, resentment, and audacious cunning, ensures his place as one of history's most notorious and fascinating forgers.