Louis Béroud (1852-1930) was a French painter whose life and career were intrinsically linked with the city of Paris, its cultural institutions, and one of the most audacious art thefts in history. While perhaps not as globally renowned as some of his Impressionist contemporaries, Béroud carved a distinct niche for himself with his meticulous realist depictions of Parisian life, particularly the hallowed interiors of its museums. His work offers a valuable window into the artistic and social milieu of late 19th and early 20th century France, and his name is forever etched in the annals of art history due to his connection with the disappearance of the Mona Lisa.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Born in Lyon in 1852, Louis Béroud's destiny as a painter of Parisian scenes was set in motion when his family relocated to the French capital when he was just nine years old. Paris, already the undisputed center of the art world, would become both his home and his primary muse. The vibrant artistic atmosphere of the city, with its bustling academies, influential Salons, and burgeoning avant-garde movements, provided a fertile ground for young artists.

Béroud sought formal training under the tutelage of Léon Bonnat (1833-1922), a highly respected and influential figure in the French academic art world. Bonnat, known for his powerful portraits and religious paintings, was a staunch advocate of traditional techniques, emphasizing strong draftsmanship, anatomical accuracy, and a sober palette. His atelier attracted numerous students, many of whom went on to achieve significant recognition. Under Bonnat's guidance, Béroud honed his skills in the realist tradition, a style that valued faithful representation of the subject matter, often with a focus on everyday life or historical accuracy. Other prominent academic painters of the era, whose influence permeated the Salon system, included Jean-Léon Gérôme and William-Adolphe Bouguereau, both masters of polished technique and grand narrative compositions.

By 1873, at the age of twenty-one, Louis Béroud was ready to present his work to the public. He made his debut at the prestigious Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain recognition, attract patrons, and establish their careers. To be accepted into the Salon was a significant achievement, and for a young artist like Béroud, it marked his formal entry into the competitive Parisian art scene.

The Development of a Realist Style

Throughout his career, Béroud remained largely faithful to the realist principles instilled by Bonnat, though his work also shows a keen awareness of light and atmosphere that sometimes bordered on an Impressionistic sensibility, particularly in his rendering of interior light. However, unlike the Impressionists such as Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, or Pierre-Auguste Renoir, who sought to capture the fleeting moment and the subjective experience of light and color, Béroud's primary focus was on detailed, objective representation. His brushwork was generally more controlled and his compositions more formally structured than those of his Impressionist peers.

His style can be seen as aligning with a broader European tradition of realism that included artists like Gustave Courbet in France, who had championed the depiction of ordinary people and unidealized reality, and later genre painters who meticulously documented urban life. Béroud’s particular strength lay in his ability to capture the intricate details of architecture, furnishings, and the human figure within complex interior spaces. He demonstrated a remarkable skill in rendering textures, from the gleam of polished wood floors to the richness of velvet drapes and the varied surfaces of sculptures and picture frames.

His palette, while often subdued in the academic tradition, was capable of capturing the subtle interplay of light and shadow, especially within the grand halls of museums or the ornate interiors of Parisian buildings. He was a master of perspective, creating convincing illusions of depth that drew the viewer into his scenes. This careful attention to detail and atmosphere made his paintings not just artistic endeavors but also valuable historical documents of the places he depicted.

Paris as Muse: Museums and Cityscapes

Louis Béroud's oeuvre is dominated by scenes of Paris. He was particularly drawn to its cultural landmarks, and above all, its museums. The Louvre, the Musée Carnavalet (dedicated to the history of Paris), and the Musée de Cluny (National Museum of the Middle Ages) were among his favorite subjects. He spent countless hours within their walls, not just as an admirer of their collections but as an artist meticulously documenting their interiors, often populated by visitors, copyists, and guards.

These museum scenes are perhaps his most characteristic works. They reveal his fascination with these temples of art, capturing not only the masterpieces they housed but also the human activity within them. His paintings often depict fellow artists at their easels, diligently copying the Old Masters, a common practice at the time for artistic training and for producing replicas for a wider market. These works provide a glimpse into the daily life of these institutions and the way art was experienced and disseminated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Artists like Edgar Degas also explored Parisian interiors, such as the opera and ballet studios, but Béroud’s focus remained steadfastly on the public spaces of art and history.

Beyond museum interiors, Béroud also painted other Parisian scenes and occasionally ventured into historical or allegorical subjects. His commitment to realism ensured that even his historical pieces were rendered with a concern for accuracy in costume and setting. His works collectively form a loving portrait of Paris during the Belle Époque and into the early decades of the 20th century, a city undergoing rapid modernization yet deeply connected to its rich past.

Representative Works and Artistic Achievements

Several of Louis Béroud's paintings stand out as representative of his skill and thematic concerns.

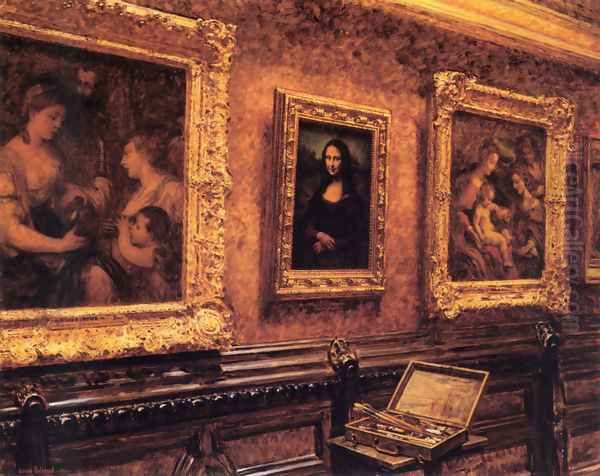

Le Salon Carré du Louvre (1883): This is one of his most celebrated works, depicting the famous Salon Carré in the Louvre Museum. This room was historically one of the most prestigious spaces in the museum, often showcasing masterpieces of the Italian Renaissance and other seminal works. Béroud’s painting captures the grandeur of the room, with its high ceilings, ornate decorations, and walls densely hung with iconic paintings. He meticulously renders the artworks on display, allowing viewers to identify specific masterpieces by artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian, or Veronese, which would have been familiar to the contemporary audience. The painting also includes figures of visitors and copyists, adding a human element and a sense of the room's function as a space for both contemplation and artistic study. Such a work demonstrates not only Béroud's technical prowess but also his deep reverence for the art of the past.

Le dôme central à Paris (1890): This painting likely depicts the central dome of one of the grand exhibition halls constructed for the Paris Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) of 1889, the same exposition for which the Eiffel Tower was built. These expositions were monumental events showcasing industrial, scientific, and artistic achievements from around the world. Béroud’s painting would have captured the architectural splendor and the vibrant atmosphere of such a pavilion, reflecting the era's optimism and pride in technological and artistic progress. The work would have highlighted the intricate ironwork and glass, characteristic of the period's innovative architecture, as seen in structures like the Grand Palais, built for the 1900 Exposition Universelle.

Notre-Dame de Paris (1922): This later work, inspired by Victor Hugo's famous novel, reportedly depicts figures in chains, conveying a sense of oppression and suffering. This suggests a departure from his more straightforward depictions of museum interiors and cityscapes, venturing into a more symbolic or narrative realm. The choice of Notre-Dame, a potent symbol of Paris and French history, combined with the literary inspiration, indicates Béroud's engagement with broader cultural and historical themes. The somber mood described would contrast with the often more serene or bustling atmosphere of his earlier museum scenes.

Throughout his career, Béroud received recognition for his contributions to French art. He was awarded an honorable mention at the Paris Salon in 1882, a significant acknowledgment from the art establishment. His success continued with a bronze medal at the Exposition Universelle of 1889, the very event he may have commemorated in Le dôme central à Paris. He also received a commemorative medal at the Exposition Universelle of 1900. These accolades solidified his reputation as a skilled and respected painter within the academic tradition. His works were acquired by important French museums, including the Louvre, the Musée Carnavalet, and the Musée de Cluny, ensuring their preservation and accessibility for future generations.

The Mona Lisa Incident: An Unexpected Role in Art History

Despite his artistic achievements, Louis Béroud is perhaps most widely remembered today for his unwitting role in one of the most sensational art crimes of the 20th century: the theft of Leonardo da Vinci's Mona Lisa from the Louvre.

On Tuesday, August 22, 1911 (some accounts say he first noticed it on Monday, August 21st, when the museum was closed for cleaning and to artists), Béroud arrived at the Louvre with the intention of sketching or making a painted copy of the Mona Lisa. This was a common practice for artists, and the Louvre, like other major museums, permitted artists to set up easels and work directly from the masterpieces. Upon reaching the Salon Carré, where the Mona Lisa was prominently displayed, Béroud was confronted with an empty space on the wall, marked only by the four iron pegs that had secured Leonardo's masterpiece.

Initially, Béroud assumed the painting had been temporarily removed by the museum's official photographers for documentation or reproduction, a not uncommon occurrence. He inquired with a nearby guard, who also seemed unconcerned, speculating that it was indeed with the photography department. However, after some time passed and the painting did not reappear, further inquiries were made. It soon became alarmingly clear that no one in authority knew the whereabouts of the Mona Lisa. The painting had not been authorized for removal. It was gone.

Louis Béroud was thus one of the very first, if not the first, to officially raise the alarm about the missing masterpiece. His discovery triggered a massive investigation and a media frenzy that catapulted the Mona Lisa from a celebrated artwork to a global icon. The Louvre was closed for a week to facilitate the search. The theft was a profound embarrassment for the French government and the museum authorities, highlighting significant lapses in security.

The newspapers were filled with speculation. Theories abounded: was it an act of sabotage by a disgruntled modernist artist? Was it stolen by a wealthy, eccentric collector? Was it a prank? Prominent figures like the poet Guillaume Apollinaire and even Pablo Picasso were briefly questioned by police, reflecting the authorities' wide net and the avant-garde's perceived rebelliousness.

The Mona Lisa remained missing for over two years. The thief was eventually revealed to be Vincenzo Peruggia, an Italian handyman who had previously worked at the Louvre. Peruggia claimed he stole the painting out of patriotic duty, believing it belonged in Italy (though Leonardo had gifted it to King Francis I of France). He was caught in December 1913 when he attempted to sell the painting to an art dealer in Florence. The Mona Lisa was recovered, exhibited briefly in Italy, and then triumphantly returned to the Louvre in early 1914.

Louis Béroud's role as the artist who discovered the theft ensured his name would be forever linked with this extraordinary event. While he continued to paint and exhibit, this incident undoubtedly became a defining, if unexpected, moment in his public persona. The story of the artist arriving to paint the world's most famous portrait, only to find it vanished, added a layer of human drama to the already sensational crime.

Béroud in the Context of His Contemporaries

Louis Béroud worked during a period of immense artistic ferment in Paris. While he adhered to a broadly academic and realist style, he was a contemporary of artists who were radically reshaping the landscape of Western art. The Impressionists had already challenged academic conventions in the 1870s and 1880s. By the time Béroud was an established painter, Post-Impressionist artists like Vincent van Gogh (though he died in 1890, his influence grew posthumously), Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, and Georges Seurat were pushing the boundaries of color, form, and expression even further.

The early 20th century saw the rise of Fauvism with artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain, and Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque. These movements represented a decisive break from the representational traditions that Béroud upheld. While Béroud's art did not engage with these avant-garde explorations, his work provides a valuable counterpoint, reflecting the enduring appeal of realism and the continued importance of academic institutions and the Salon system, even as they were being challenged.

His dedication to depicting museum interiors can be seen as a form of cultural preservation, a meticulous recording of how art was displayed and experienced. In this, he shares some common ground with earlier artists like Hubert Robert (1733-1808), who famously painted picturesque views of Roman ruins and the Louvre's galleries, sometimes in states of imagined decay or transformation. However, Béroud's approach was less romanticized and more documentary.

It is also interesting to note the existence of another Parisian painter of city life, Jean Béraud (1849-1935, note the different spelling). Though not related, Jean Béraud was also known for his lively depictions of Parisian society, street scenes, and interiors, often with a slightly more anecdotal or socially observant character than Louis Béroud's more formal museum views. Both artists, however, contributed significantly to the visual record of Belle Époque Paris.

Legacy and Historical Significance

Louis Béroud passed away in Paris in 1930. His legacy is multifaceted. As a painter, he was a skilled practitioner of realism, creating works of considerable charm and technical proficiency. His paintings of Parisian museums are particularly important, offering detailed and atmospheric records of these institutions at a specific point in time. They document not only the architecture and the art collections but also the social dynamics of museum-going and artistic practice.

His works are held in the collections of major French museums, a testament to their artistic and historical value. For art historians and social historians, Béroud's paintings serve as visual documents, providing insights into the cultural life of Paris, the organization of its museums, and the tastes of the era. They capture a world where the museum was a central institution for artistic education and public edification.

Beyond his artistic output, Béroud's accidental involvement in the Mona Lisa theft has secured him a unique place in art history. He became an eyewitness to a pivotal moment, and his actions helped to initiate the response to one of the most famous art heists ever. This connection, while perhaps overshadowing his other achievements in popular memory, also serves to draw attention to his life and work.

In conclusion, Louis Béroud was more than just the man who noticed the Mona Lisa was missing. He was a dedicated artist who lovingly chronicled the cultural heart of Paris. His paintings invite us to step back in time, to wander the hallowed halls of the Louvre alongside him, and to appreciate the enduring power of art, both as a subject for creation and as a treasure to be cherished and protected. His art reflects a deep understanding of Parisian culture and history, and his career stands as a testament to the enduring appeal of realist painting in an age of revolutionary artistic change.