Utagawa Hiroshige, born Andō Tokutarō, stands as one of the most celebrated and influential figures in the history of Japanese art. Active during the late Edo period, he became synonymous with the ukiyo-e genre, particularly renowned for his evocative landscape prints (fūkei-ga) and depictions of birds and flowers (kachō-e). His work captured the transient beauty of Japan's natural scenery, its changing seasons, and the daily life along its famous routes, leaving an indelible mark not only on Japanese art but also profoundly impacting Western artists centuries later. Series like The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo remain iconic, showcasing his unique ability to blend realism with poetic sentiment.

From Samurai Scion to Ukiyo-e Apprentice

Hiroshige entered the world in 1797 in Edo (modern-day Tokyo), specifically in the Yaesu Quay area near Edo Castle. His birth name was Andō Tokutarō. He hailed from a low-ranking samurai family; his father, Andō Gen'emon, held an inherited position as a fire warden (hikeshi dōshin) for the Edo Castle precinct. This hereditary post provided a modest but stable position within the samurai hierarchy. However, Hiroshige's youth was marked by loss. His mother passed away in early 1809, and his father followed later the same year, leaving the young Tokutarō orphaned at the tender age of twelve.

Despite his samurai lineage and the expectation that he might follow in his father's footsteps (a duty he did briefly inherit and perform), Hiroshige displayed a strong inclination towards art from an early age. Sources suggest he may have initially sought instruction from Okajima Rinsai, a painter of the Kanō school. His true path, however, lay within the popular art form of ukiyo-e, woodblock prints and paintings depicting the "floating world" of urban pleasures, famous beauties, kabuki actors, and scenic views.

![From The Series Tokaido Tsugi No

Uchi [the Fifty-three Stations Of The Tokaido], Mariko - Meibutsu

Chamise [mariko - The Local Speciality Shop], Travellers Eating The

Local Yam Paste Delicacy Tororoshiru by Utagawa or Ando Hiroshige](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/2324622/m/utagawa-or-ando-hiroshige-from-the-series-tokaido-tsugi-no-uchi-the-fiftythree-stations-of-the-tokaido-mariko-meibutsu-chamise-mariko-the-local-speciality-shop-travellers-eating-the-local-yam-paste-delicacy-tororoshiru-2bbaf87d.jpg)

Around the age of 14, in 1811, Hiroshige sought apprenticeship under the leading ukiyo-e master Utagawa Toyokuni I, head of the prestigious Utagawa school. However, Toyokuni's studio was already full. Instead, Hiroshige was accepted into the studio of Utagawa Toyohiro, another prominent artist of the Utagawa school known for his graceful bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women) and illustrative work, though less commercially dominant than Toyokuni. This proved to be a fortuitous connection. Toyohiro was a skilled and perhaps more subtle artist, whose influence likely steered Hiroshige towards a more lyrical and atmospheric style than the bolder theatricality often associated with Toyokuni.

In 1812, after just a year of study, Hiroshige was granted his artist's name (gō). Following Utagawa school tradition, he adopted the first character of his master's name (Hiro-) and combined it with an alternative reading of the first character of his given name, Tokutarō (-shige). Thus, Andō Tokutarō became Utagawa Hiroshige, formally joining the lineage of one of the most powerful art schools of the era. Throughout his life, he would use other names and pseudonyms, including variations on his birth name like Andō Jūemon, Andō Tetsuzō, and Andō Tokubei, and later art names like Ichiyūsai and Ryūsai, but Utagawa Hiroshige became the name synonymous with his artistic genius. The informal nickname "Ando Hiroshige," sometimes seen, is a conflation of his family name and art name and was not a name he used himself.

Early Career and the Turn to Landscape

Hiroshige's initial works, starting around 1818, followed the typical trajectory for an Utagawa school apprentice. He produced actor prints (yakusha-e), images of beautiful women (bijin-ga), and book illustrations, genres dominated by his school seniors like Utagawa Kunisada (later Toyokuni III) and Utagawa Kuniyoshi. While competent, his early works in these popular fields did not immediately distinguish him from his contemporaries. He showed skill, but his unique voice had yet to fully emerge.

A significant turning point appears to have occurred around 1830-1831. While he continued to produce prints in various genres, Hiroshige began to focus more intently on landscapes and nature studies. This shift coincided with, and was likely influenced by, the immense success of Katsushika Hokusai's groundbreaking series Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (c. 1830-1832). Hokusai, an older, independent master outside the major schools, had dramatically elevated landscape as a primary subject for ukiyo-e, demonstrating its popular appeal.

There's an anecdote, possibly apocryphal, that Hiroshige sought to study under Hokusai but was rebuffed. Whether true or not, Hokusai's work undoubtedly made a significant impression. However, Hiroshige did not merely imitate Hokusai's dynamic compositions and dramatic flair. Instead, he began developing his own distinct approach to landscape – one characterized by a quieter, more poetic sensibility, focusing on atmosphere, weather, and the subtle interplay of human activity within the natural world. His early landscape series, such as Famous Places in the Eastern Capital (Tōto Meisho), began to showcase this emerging style.

The Tōkaidō Road: A Journey to Fame

The breakthrough that cemented Hiroshige's reputation came in 1832. An opportunity arose for him to travel from Edo to Kyoto along the Tōkaidō, the main coastal highway connecting the two capitals. He journeyed as part of an official procession transporting horses as a symbolic gift from the Shōgun to the Emperor. This journey provided him with firsthand experience of the diverse landscapes, bustling post stations, and varied weather conditions along this famous route.

Upon his return to Edo, Hiroshige translated his sketches and memories into what would become his most celebrated work: The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (Tōkaidō Gojūsan-tsugi). Published between 1833 and 1834 by the Hōeidō publishing house, the series consists of 55 prints in total – one for each of the 53 post stations, plus one for the starting point in Edo (Nihonbashi) and one for the final destination in Kyoto (Sanjō Ōhashi).

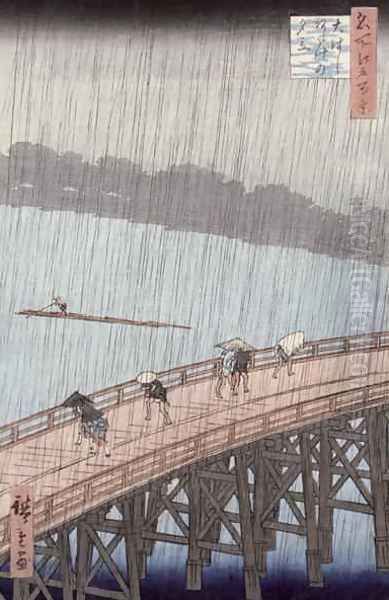

The series was an unprecedented success. Unlike earlier depictions of the Tōkaidō, which often focused on processions or famous landmarks in a more documentary style, Hiroshige captured the experience of the journey. He depicted travelers battling sudden rain showers (Shōno), crossing rivers, resting at inns, and admiring scenic vistas under snow (Kanbara) or moonlight. His masterful use of perspective, atmospheric effects achieved through sophisticated color gradation (bokashi), and his ability to convey mood and narrative within each scene resonated deeply with the public. The series established Hiroshige as a leading landscape artist, rivaling even the great Hokusai in popularity. Its success led to numerous subsequent Tōkaidō series by Hiroshige himself, produced for different publishers and in various formats.

Mastering the View: Signature Style and Techniques

Following the triumph of the Hōeidō Tōkaidō, Hiroshige became primarily known as the "poet of landscape." His style, while evolving over his career, maintained several key characteristics that distinguished him from other ukiyo-e artists, including his Utagawa school colleagues like the prolific Kunisada or the dramatic Kuniyoshi, and the singular Hokusai.

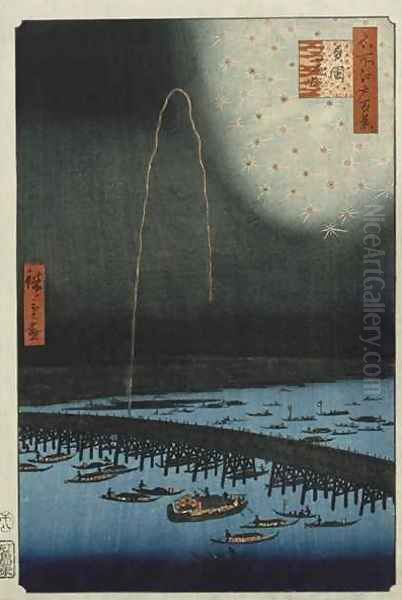

Hiroshige excelled at capturing atmosphere and specific weather conditions. Rain, snow, mist, and moonlight feature prominently in his work, rendered with remarkable subtlety and effectiveness. His print Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake from the later Edo Views series is a prime example, conveying the immediacy and sensory experience of a downpour. He achieved these effects through masterful collaboration with his block carvers and printers, utilizing techniques like bokashi (tonal gradation) to create soft transitions in sky and water, and intricate carving to depict fine lines of rain or delicate snowflakes.

His compositions often displayed a quiet lyricism and intimacy. While Hokusai's landscapes frequently emphasized dramatic power and monumental scale, Hiroshige's views often felt more personal and relatable. He skillfully integrated human figures into his landscapes, not as dominant subjects, but as small elements whose activities – traveling, working, resting – added narrative interest and scale, emphasizing the harmony or sometimes the struggle between humanity and nature.

Hiroshige also demonstrated a keen understanding of perspective, likely influenced by Western prints (uki-e, or perspective pictures) that were circulating in Japan. He effectively used foreground elements, diagonal lines, and receding planes to create a sense of depth and space, drawing the viewer into the scene. This is particularly evident in his later works, where bold cropping and unusual vantage points add dynamism and modernity to his compositions. His use of color was typically harmonious and evocative, often employing blues and greens to create serene moods, though he could also use vibrant colors effectively when the scene demanded it.

Edo in Focus: One Hundred Famous Views

Towards the end of his life, between 1856 and 1858, Hiroshige embarked on his last great masterpiece, the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Edo Hyakkei). Published posthumously in part, this ambitious series eventually comprised 119 prints (plus a title page), showcasing the landscapes, temples, shrines, entertainment districts, and seasonal beauty of his beloved home city.

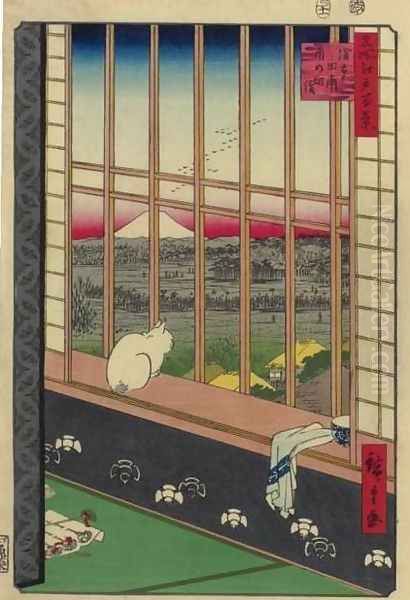

This series is notable for its innovative compositions and striking use of a vertical format, which was unusual for landscape prints at the time. Hiroshige frequently employed bold foreground elements – an oversized lantern, the mast of a boat, blossoming plum branches – dramatically cropped to frame the distant view. This technique created a sense of immediacy and visual dynamism, anticipating compositional devices later explored by Western photographers and painters.

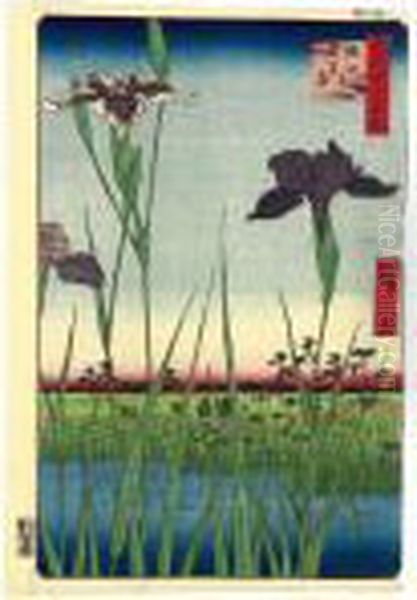

Prints like Plum Garden at Kameido, with its striking abstract pattern of branches dominating the foreground, and Asakusa Ricefields and Torinomachi Festival, with its unsettlingly intimate view of a cat looking out from a window high above the city, demonstrate his continued artistic experimentation even late in his career. The series as a whole provides an unparalleled visual record of Edo at a specific moment in time, just before Japan's rapid modernization began in the Meiji era. It captures the city's unique blend of urban energy and natural beauty, its festivals, and its quiet corners, solidifying Hiroshige's status as the definitive visual chronicler of mid-19th century Edo.

Other Notable Works and Series

While the Tōkaidō and Edo Views are his most famous series, Hiroshige was incredibly prolific, credited with designing over 5,000 prints during his career. His landscape work extended far beyond these two series. He created numerous other sets depicting famous places, including:

The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kiso Kaidō (Kiso Kaidō Rokujūkyū-tsugi, c. 1834–1842): A collaboration with Keisai Eisen, depicting the inland mountain route connecting Edo and Kyoto. Hiroshige completed the majority of the prints, showcasing his ability to render rugged mountain scenery.

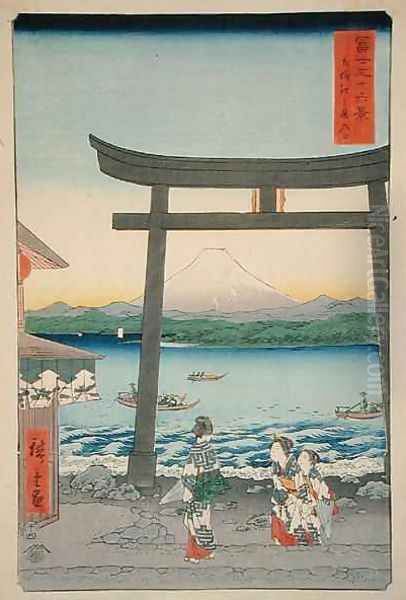

Famous Views of the Sixty-odd Provinces (Rokujūyoshū Meisho Zue, 1853–1856): An extensive series depicting a famous site from each of Japan's traditional provinces, demonstrating his versatility in capturing diverse geographical features.

Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji (Fuji Sanjūrokkei, 1852 and 1858): Hiroshige produced two series with this title, inevitably inviting comparison with Hokusai's earlier masterpiece. While perhaps less iconic than Hokusai's set, Hiroshige's Fuji views display his characteristic lyricism and atmospheric sensitivity.

Beyond landscapes, Hiroshige was also a master of kachō-e, prints depicting birds, flowers, fish, and insects. These smaller-format prints often combined meticulous observation of nature with poetic inscriptions (haiku or kyōka), showcasing his delicate brushwork and refined sense of design. He continued to produce other types of prints throughout his career, including historical scenes and illustrations, though landscapes remained his primary focus and legacy.

Life's Challenges and Final Years

Despite his artistic success and popularity, Hiroshige's later life was not without hardship. The economic and social instability of the late Edo period, coupled with reforms aimed at curbing luxury (the Tenpō Reforms), impacted the publishing industry and artists' incomes. There are accounts suggesting that Hiroshige faced financial difficulties in his later years, sometimes referred to disparagingly as a "three-mon painter," implying his work sold cheaply. While the extent of his poverty may be debated, it seems clear he did not achieve the lasting financial security his fame might suggest.

He continued working diligently until the end. In 1858, Edo was struck by a devastating cholera epidemic. Hiroshige contracted the disease and died on the 12th day of the ninth month (October 12th according to the Western calendar), aged 61. He left behind a poignant death poem: "I leave my brush in the East / And set forth on my journey. / I shall see the famous places in the Western Land." The "Western Land" refers to the Buddhist paradise. It is said that his funeral expenses were covered by friends and colleagues, a testament to the personal regard in which he was held, even if official accolades were modest during his lifetime. His artistic legacy was carried on, albeit with less distinction, by his pupils, notably Hiroshige II (his adopted son) and later Hiroshige III.

Hiroshige's Enduring Legacy in Japan

Within the history of ukiyo-e, Hiroshige is universally acknowledged as one of the last great masters of the tradition. Alongside Katsushika Hokusai and perhaps Kitagawa Utamaro (the master of bijin-ga), he represents the pinnacle of Japanese woodblock printing. While Hokusai is often lauded for his dynamism, imaginative power, and technical brilliance, Hiroshige is celebrated for his poetic sensibility, his mastery of atmosphere, and his intimate portrayal of the Japanese landscape and its relationship with human life.

His work marked a high point in landscape ukiyo-e, bringing a new level of emotional depth and atmospheric realism to the genre. He captured the specific character of places and moments in time with unparalleled sensitivity. His prints were widely disseminated and enjoyed by the urban populace of Edo, offering vicarious travel experiences and celebrating the beauty of their own city and country. Even today, his images profoundly shape the popular imagination of traditional Japan.

Influence Across Borders: Hiroshige and the West

Hiroshige's influence extends far beyond Japan. Following the opening of Japan to the West in the mid-19th century, Japanese art, particularly ukiyo-e prints, began to flood European and American markets. This influx sparked a craze known as Japonisme, profoundly impacting Western art and design. Hiroshige, along with Hokusai and Utamaro, was among the most collected and admired Japanese artists.

Impressionist and Post-Impressionist painters were particularly captivated by Hiroshige's work. His innovative compositions, flattened perspectives, use of bold outlines, asymmetrical arrangements, and atmospheric effects offered a fresh alternative to Western academic traditions.

Vincent van Gogh was an ardent admirer and collector. He famously created oil painting copies of two prints from One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi Bridge and Atake and Plum Garden at Kameido (retitled Japonaiserie: Bridge in the Rain and Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree). He absorbed Hiroshige's compositional ideas and vibrant color sense into his own expressive style.

Claude Monet amassed a large collection of Japanese prints, including works by Hiroshige, which are still displayed at his home in Giverny. The influence can be seen in Monet's series paintings (like the Haystacks or Rouen Cathedral), which explore changing light and atmosphere, echoing Hiroshige's sensitivity to transient effects. His Japanese bridge at Giverny was directly inspired by prints like Hiroshige's.

James Abbott McNeill Whistler incorporated Japanese aesthetic principles, including asymmetrical compositions and tonal harmonies reminiscent of Hiroshige, into his paintings, particularly his "Nocturnes."

Other artists like Edgar Degas, Mary Cassatt, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Paul Gauguin also drew inspiration from the compositional freedom, everyday subject matter, and decorative qualities found in Hiroshige's prints and ukiyo-e in general.

Hiroshige's art thus served as a crucial bridge between Eastern and Western artistic sensibilities, contributing significantly to the development of modern art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Collecting Hiroshige: Where to Find His Art

Today, Hiroshige's prints are held in numerous museums and private collections worldwide. Due to the nature of woodblock printing, multiple impressions exist for many of his designs, varying in quality, condition, and color state depending on when they were printed.

Major institutional collections holding significant numbers of Hiroshige's works include:

Tokaido Hiroshige Museum of Art, Shizuoka, Japan: The first museum dedicated primarily to Hiroshige, holding around 1,400 works, focusing on his landscape series.

Tokyo National Museum, Japan: Holds a vast collection of ukiyo-e, including many Hiroshige prints.

Ōta Memorial Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan: Specializes in ukiyo-e and has a substantial Hiroshige collection.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, USA: Possesses one of the largest and finest collections of Japanese art outside Japan, including extensive holdings of Hiroshige.

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA: Features a strong collection of Japanese prints, with numerous examples by Hiroshige.

British Museum, London, UK: Holds a significant collection of Japanese art, including iconic Hiroshige prints.

Victoria and Albert Museum, London, UK: Also has important holdings of Japanese prints.

Art Institute of Chicago, USA: Known for its excellent collection of Japanese prints.

Harvard Art Museums, Cambridge, USA: Holds notable examples, including prints from the Edo Views series.

Guimet Museum (Musée national des arts asiatiques-Guimet), Paris, France: A major European center for Asian art with significant Japanese print collections.

Other Japanese institutions mentioned in the source material, such as the Izumi City Kuboso Memorial Museum of Arts, Yamaguchi Prefectural Hagi Uragami Museum, and potentially others, also house important works.

Conclusion: The Enduring Vision

Utagawa Hiroshige remains a towering figure in Japanese art history and a globally recognized master of the woodblock print. His genius lay in his ability to transform ordinary landscapes and scenes of daily life into images of extraordinary beauty and poetic resonance. He captured the specific moods of places and moments – the quiet hush of snow, the drama of a sudden storm, the tranquility of moonlight – with unparalleled skill and sensitivity. Through series like The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō and One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, he not only created an enduring visual record of 19th-century Japan but also crafted a unique artistic language that transcended cultural boundaries, inspiring artists across the globe. His vision of Japan, imbued with lyricism, atmosphere, and a deep appreciation for the transient beauty of the natural world, continues to captivate viewers today.