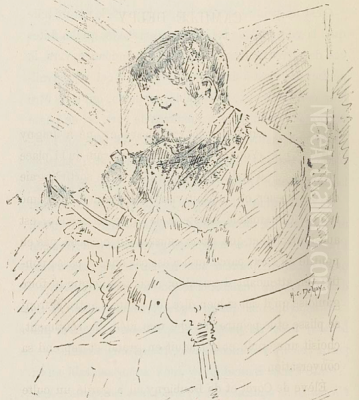

Hippolyte Camille Delpy stands as a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in the rich tapestry of 19th-century French landscape painting. Born in Joigny, in the Yonne department of France, on April 16, 1842, and passing away in Paris on June 5, 1910, Delpy's life spanned a period of immense artistic transformation. He emerged from the traditions of the Barbizon School, directly learning from one of its masters, yet his work evolved, absorbing the atmospheric concerns and brighter palettes that would characterize Impressionism. Primarily a landscape artist, Delpy dedicated his career to capturing the subtle beauties of the French countryside, particularly its rivers, villages, and the fleeting effects of light and weather. His paintings offer a unique blend of naturalistic observation and personal poetic interpretation, securing his place as an important transitional artist.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Born into a comfortably middle-class family, Hippolyte Camille Delpy enjoyed advantages that allowed him to pursue an artistic path. His family's support was crucial in enabling his early training. The most formative influence on the young Delpy was undoubtedly Charles-François Daubigny (1817-1878), a leading figure of the Barbizon School and a pioneer of plein air (outdoor) painting. Daubigny was a friend of the Delpy family, and recognizing the young Hippolyte's talent, he took him under his wing. This mentorship began informally, likely involving observation and guidance during Daubigny's painting excursions.

Daubigny was renowned for his innovative approach, often painting directly from nature aboard his studio boat, "Le Botin," along the rivers Oise and Seine. Delpy frequently accompanied his master on these trips, absorbing Daubigny's techniques for capturing the fluidity of water, the reflections on its surface, and the specific atmospheric conditions of the riverside landscapes. This direct immersion in the practice of outdoor painting, observing Daubigny's methods firsthand, provided Delpy with an invaluable foundation. Daubigny's emphasis on sincerity before nature and his increasingly loose brushwork were key lessons that Delpy would carry throughout his career.

The Influence of the Barbizon School

Delpy's artistic roots lie firmly within the Barbizon School, the movement that dominated French landscape painting from the 1830s to the 1870s. Centered around the village of Barbizon near the Forest of Fontainebleau, this group of artists rejected the idealized, historical landscapes favored by the Neoclassical tradition. Instead, they sought a more truthful, unadorned depiction of rural France. Key figures included Théodore Rousseau, Jean-François Millet, Narcisse Virgilio Díaz de la Peña, Constant Troyon, and Jules Dupré, alongside Delpy's mentor, Daubigny.

While Daubigny was his primary teacher, Delpy was also profoundly influenced by Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796-1875), another giant associated with the Barbizon movement, though distinct in his more lyrical and poetic approach. Corot's mastery of tonal values, his ability to evoke mood through subtle harmonies of color, and his often silvery light left a lasting impression on Delpy. Delpy's work often seems to synthesize the influences of these two masters: the robust naturalism and contemporary feel of Daubigny combined with the softer, more atmospheric and sometimes romanticized sensibility of Corot. He embraced the Barbizon commitment to direct observation but filtered it through his own temperament, often seeking out specific times of day – dawn, dusk, sunset – to capture more evocative lighting effects.

Developing a Personal Style

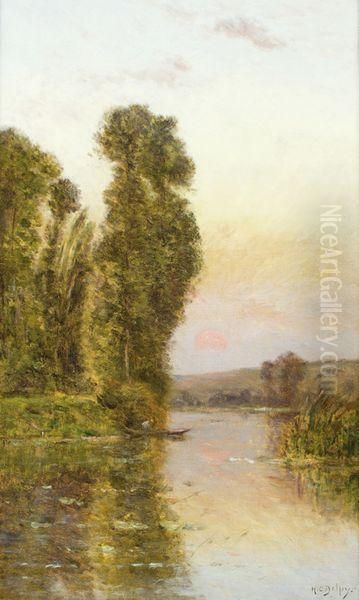

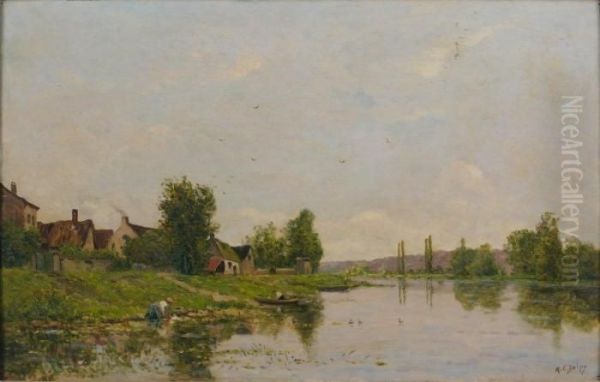

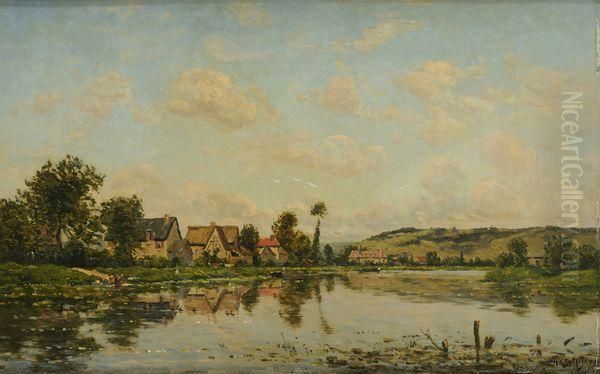

While deeply indebted to his Barbizon predecessors, Delpy was not merely an imitator. He forged a distinct artistic identity, characterized by a sensitive handling of light and atmosphere, a preference for certain motifs, and an evolving technique that reflected the changing artistic currents of his time. His primary subjects were landscapes, often featuring water – rivers, ponds, and coastal scenes. The Seine and Oise rivers, familiar from his excursions with Daubigny, remained favorite locales throughout his career.

Delpy excelled at capturing the nuances of changing light. His sunset and twilight scenes are particularly noteworthy, often featuring warm, glowing skies reflected in calm waters. He employed a palette that could range from the subtle, silvery grays and greens reminiscent of Corot to richer, more vibrant hues, especially in his depictions of sunsets or autumnal foliage. His brushwork, while grounded in Barbizon naturalism, often displayed a greater freedom and texture than that of the earlier generation, hinting at the burgeoning Impressionist aesthetic. He paid close attention to detail but avoided photographic precision, focusing instead on the overall mood and harmony of the scene.

His depictions of snow scenes, such as the notable La Rue des Martyrs; Paris in the Snow (1890), showcase his skill in handling cool palettes, primarily blues and grays, to convey the specific light and atmosphere of a winter's day. In this particular work, the use of a narrow street perspective creates a sense of depth and intimacy, demonstrating his compositional abilities. Delpy's landscapes frequently include elements of rural life – washerwomen by the river, fishermen in boats, small villages nestled in the countryside – grounding his poetic visions in observed reality.

Engagement with Auvers-sur-Oise and Impressionism

Around 1873, Delpy settled for a time in Auvers-sur-Oise, a village on the Oise river that had become a magnet for artists. This period proved significant for his artistic development, bringing him into contact with key figures associated with Impressionism. While living in Auvers, he encountered Camille Pissarro (1830-1903) and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906), who were both working there, exploring new ways of representing landscape and light. Claude Monet (1840-1926), another leading Impressionist, was also part of this artistic milieu, though perhaps less directly connected to Delpy during this specific period.

Although Delpy never formally joined the Impressionist group or exhibited in their independent shows, his interactions with these artists undoubtedly influenced his work. His palette sometimes brightened, his brushwork became looser, and his interest in capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere intensified, aligning him with Impressionist concerns. However, he retained a stronger sense of structure and a more traditional approach to composition derived from his Barbizon training. He can be seen as occupying a space between the established Barbizon tradition and the radical innovations of Impressionism, absorbing elements from the latter without fully abandoning the former. His connection with Cézanne, noted as one of mutual appreciation during Salon encounters, highlights his engagement with the evolving art scene. Other Impressionists like Alfred Sisley (1839-1899) and Berthe Morisot (1841-1895) were also active during this period, contributing to the vibrant artistic dialogue from which Delpy drew inspiration, even if indirectly.

Travels and Broadening Horizons

Delpy's quest for landscape subjects was not confined to France. Driven by a desire for new motifs and perhaps different qualities of light, he undertook travels abroad. Records indicate he visited the Netherlands, a country with a rich tradition of landscape painting dating back to the Dutch Golden Age masters like Jacob van Ruisdael and Meindert Hobbema. The flat landscapes, canals, and distinctive skies of Holland likely offered fresh inspiration.

He also traveled to England. While specific influences are not always documented, exposure to the English landscape tradition, perhaps the works of John Constable or J.M.W. Turner known for their atmospheric effects and innovative techniques, could have resonated with Delpy's own artistic interests. Furthermore, evidence suggests he even traveled to the United States, a less common destination for French landscape painters of his generation. These journeys broadened his visual vocabulary and provided him with diverse subjects, enriching the scope of his work beyond the familiar French countryside. This willingness to explore demonstrates an artistic curiosity and a commitment to finding the ideal landscape to match his vision.

Exhibitions, Recognition, and the Salon System

Delpy was a consistent participant in the official Paris Salon, the most important art exhibition in France for much of the 19th century. Making his debut likely in the late 1860s, he achieved early recognition with an honorable mention in 1870. The Salon was the primary venue for artists to gain visibility, attract patrons, and build their reputations. Delpy's regular participation indicates his ambition and his ability to meet the standards of the Salon jury, even as his style evolved.

He achieved significant milestones within the Salon system. In 1884, he was awarded a third-class medal for a work titled Solitude Medal. This recognition affirmed his standing among his peers. His success continued, and his work was selected for inclusion in the prestigious Exposition Universelle (World's Fair) held in Paris in 1889, where he received another honorable mention. This international showcase brought his art to a wider audience. He also received accolades later in his career, including recognition at the 1900 Salon.

Beyond the official Salon, Delpy also exhibited in other venues. A notable exhibition took place in 1894 at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris, a prominent gallery that often showcased artists who bridged traditional and more modern styles. His participation suggests his established reputation and market appeal. These exhibitions, both within the official system and at private galleries, were crucial for Delpy's career, allowing him to sell works and solidify his position in the Parisian art world.

Notable Works and Artistic Themes

Hippolyte Camille Delpy's oeuvre is rich with evocative landscapes that capture the essence of the French countryside. Several works stand out as representative of his style and thematic concerns:

La Rue des Martyrs; Paris in the Snow (1890): This painting exemplifies his skill in depicting urban winter scenes. Using a cool palette dominated by blues and grays, Delpy captures the muffled quietude of snow-covered Paris. The narrow perspective of the street draws the viewer in, emphasizing the verticality of the buildings and creating a strong sense of place and atmosphere. It showcases his ability to handle complex light conditions and render architectural details within a cohesive atmospheric envelope.

Solitude Medal (1884): The work that earned him a medal at the Salon, its title suggests a more symbolic or allegorical dimension than his typical landscapes. While the specific imagery isn't described in the provided sources, the title points towards themes of introspection, quietude, or perhaps the solitary experience of nature, themes often subtly present in landscape painting.

River Scenes (e.g., Sunset by the River, The Dusk of the River, Pêcheur au soleil couchant, Bord de Seine): These titles represent a recurring and central theme in Delpy's work. He was fascinated by the play of light on water, especially during the transitional hours of dawn and dusk. His sunset scenes often feature vibrant colors reflected in the water, while his dusk paintings evoke a sense of tranquility and mystery. The presence of fishermen or washerwomen adds a human element, suggesting the harmonious relationship between rural life and the natural environment. These works clearly show the legacy of Daubigny's river studies but are infused with Delpy's own sensitivity to color and mood.

Rural Landscapes (e.g., Harvest in the Morning, Village en bord d'étang): Delpy also painted broader countryside views, depicting agricultural activities like harvesting or capturing the charm of small villages situated near ponds or rivers. These works celebrate the pastoral beauty of France, continuing the Barbizon tradition of finding significance in everyday rural scenes.

A Painting to-Come (Undated): This intriguing work, mentioned in connection with the Arts Incohérents, stands apart. Described as a blank canvas within a frame decorated with characters, it represents a radical departure and a conceptual gesture unusual for a landscape painter of his time. It suggests an experimental side to Delpy, willing to question the very nature of painting and representation.

These examples illustrate the range of Delpy's subjects and his consistent focus on capturing atmospheric effects and the poetic qualities of the landscape. His works are held in various public collections, including the Musée Carnavalet and the Musée de la Ville de Paris, as well as numerous private collections worldwide.

The "Arts Incohérents" and Artistic Innovation

Delpy's participation in the Salon des Arts Incohérents (Salon of Incoherent Arts) in 1883 reveals a lesser-known, more experimental facet of his artistic personality. Founded by the Parisian writer and publisher Jules Lévy, the Arts Incohérents movement was satirical and deliberately anti-establishment, poking fun at the seriousness of the official Salon and the emerging avant-garde movements. It featured humorous, absurd, and often conceptually driven works, predating later movements like Dada and Surrealism in its playful iconoclasm.

Delpy's contribution, the aforementioned A Painting to-Come – essentially a blank canvas presented as art – fits perfectly within the spirit of the Arts Incohérents. This piece can be interpreted in several ways: as a critique of artistic conventions, a commentary on the potentiality of the blank canvas, or simply a witty gesture. Its creation demonstrates that Delpy, despite his grounding in the more traditional landscape genre, was aware of and willing to engage with the more radical artistic currents and conceptual ideas circulating in Paris. This participation, alongside figures often associated with humor and satire like Alphonse Allais, adds an unexpected layer to our understanding of Delpy, suggesting an artist with intellectual curiosity and a willingness to step outside conventional boundaries.

Later Life, Legacy, and Market Presence

In the later years of his life, specifically after 1909, Hippolyte Camille Delpy's health began to decline significantly, eventually confining him to bed for extended periods. Despite his failing health, his dedication to his art remained strong. Remarkably, he managed to participate in the Salon of 1910, submitting work even while gravely ill. He passed away shortly thereafter, on June 5, 1910, in Paris, the city where he had established his career.

Delpy left behind a substantial body of work that continues to be appreciated for its sensitivity and technical skill. His legacy lies in his successful synthesis of Barbizon naturalism with a lighter palette and more atmospheric approach that anticipated Impressionism. He occupies an important position as a transitional figure, demonstrating how the lessons of Corot and Daubigny could be adapted to reflect newer artistic sensibilities without fully embracing the Impressionist revolution. While perhaps not as famous today as the leading Impressionists like Monet or Renoir, or the core Barbizon figures like Millet, Delpy was highly regarded during his lifetime and maintained a successful career.

His works remain popular on the art market. Auction records show consistent sales at reputable houses like Sotheby's, Doyle New York, and Osenat Fontainebleau. For instance, a painting titled The Dusk of the River sold for €5,200 in October 2024, exceeding its estimate, indicating continued collector interest. The prices achieved for his works reflect his established reputation as a skilled and appealing painter of the French landscape tradition. His paintings are valued for their aesthetic charm, historical significance, and their connection to two major movements in French art history.

Conclusion: An Enduring Vision of the French Landscape

Hippolyte Camille Delpy was more than just a follower of Daubigny or an echo of Corot. He was a distinct artistic voice who carved out his own niche within the competitive Parisian art world of the late 19th century. Grounded in the Barbizon school's dedication to nature, he embraced the lessons of plein air painting and realistic observation. Yet, he infused his work with a personal lyricism, a sensitivity to the nuances of light and atmosphere, and an evolving technique that acknowledged the innovations of Impressionism.

His landscapes, particularly his beloved river scenes at dawn and dusk, capture a specific, often tranquil and poetic, vision of the French countryside. His participation in the official Salons, the awards he won, and his presence in international exhibitions testify to the recognition he achieved during his lifetime. Even his brief foray into the conceptual humor of the Arts Incohérents adds depth to his profile. Today, Delpy's paintings continue to resonate, offering viewers serene and beautifully rendered glimpses of a bygone era, and securing his place as a significant contributor to the enduring tradition of French landscape painting, a vital link connecting the realism of Barbizon with the light-filled canvases of the Impressionists. His contemporaries included not only his teachers and Impressionist contacts but also figures like Eugène Boudin, known for his coastal scenes, and Henri Harpignies, another long-lived landscape painter who bridged similar stylistic periods. Delpy's art remains a testament to a dedicated career spent observing and interpreting the subtle beauties of the natural world.