Introduction: An American Vision

Jonathan Eastman Johnson stands as a pivotal figure in the landscape of nineteenth-century American art. Born on July 29, 1824, in Lovell, Maine, and passing away on April 5, 1906, in New York City, Johnson forged a career that captured the multifaceted nature of American identity during a period of profound transformation. He was a master of both intimate portraiture and vibrant genre scenes, earning him the laudatory, if somewhat simplifying, nickname "The American Rembrandt." His work provides invaluable visual documentation and insightful commentary on the social fabric, domestic life, and political currents of his era, from the antebellum South to the rural North and the drawing rooms of the Gilded Age elite.

Johnson's artistic journey was marked by a unique blend of native sensibility and sophisticated European training. He possessed an innate talent for observation and a deep empathy for his subjects, whether they were enslaved individuals in Washington D.C., farmers tapping maple trees in Maine, or powerful industrialists in New York. His ability to render detail with precision, combined with a masterful handling of light and shadow, allowed him to create images that were both realistic and deeply resonant. He navigated the complex social and artistic terrains of his time, becoming a co-founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a respected member of the National Academy of Design, solidifying his place not just as a painter, but as a significant cultural force.

Early Life and Artistic Awakenings

Eastman Johnson's roots were firmly planted in New England. Though born in Lovell, he spent much of his youth in Fryeburg and later Augusta, Maine, where his father, Philip Carrigan Johnson, held influential positions, including serving as Maine's Secretary of State. This connection to prominent figures likely provided the young Johnson with early exposure to individuals of note and perhaps eased his entry into certain social circles later in his career. His artistic inclinations emerged early, though not initially through formal academic channels.

Around 1840, at the age of sixteen, Johnson began his professional life not with oil paints, but with the tools of a different trade. He apprenticed briefly at a lithography shop owned by John H. Bufford in Boston. While lithography offered technical training in drawing and reproduction, Johnson quickly gravitated towards portraiture, initially working primarily in crayon and charcoal. This medium allowed him to develop his skills in capturing likenesses with speed and accuracy, a foundation that would serve him well throughout his career.

His burgeoning talent soon led him away from Boston. He established himself as an itinerant portraitist, working in Newport, Rhode Island, and eventually finding significant success in Washington, D.C., beginning around 1845. Leveraging his father's connections, he secured studio space within the U.S. Capitol building and gained commissions to draw leading political and social figures. His sitters during this period included the venerable former First Lady Dolley Madison and the statesman John Quincy Adams, demonstrating his early ability to attract high-profile clients. He also drew the famed poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and his family, forging links with the literary elite.

The European Sojourn: Refining Technique and Vision

By the late 1840s, despite his success as a portrait draftsman, Johnson recognized the need for more formal and rigorous training, particularly in oil painting, which was considered the higher art form. Like many ambitious American artists of his generation, he looked towards Europe. In 1849, funded by the sale of his earlier works and possibly with family support, Johnson embarked on a transformative journey abroad that would last nearly six years.

His first major destination was Düsseldorf, Germany, a prominent center for academic art training. He enrolled at the renowned Kunstakademie and studied alongside or under the influence of figures associated with the Düsseldorf school, known for its detailed realism and narrative clarity. Significantly, he spent time in the studio of the German-American painter Emanuel Leutze, who was then working on his monumental Washington Crossing the Delaware. While historical accounts sometimes overstate Johnson's direct contribution, it's documented that he assisted Leutze, perhaps providing research or details regarding Washington's uniform, gaining invaluable exposure to the creation of large-scale historical compositions.

Seeking broader influences, Johnson moved to The Hague in the Netherlands in 1851. This proved to be a crucial phase. He immersed himself in the study of the Dutch Masters of the 17th century – artists like Rembrandt van Rijn, Johannes Vermeer, Frans Hals, and Jan Steen. The Dutch emphasis on domestic interiors, nuanced light effects, psychological depth in portraiture, and the dignity of everyday life resonated deeply with Johnson. He spent nearly four years there, honing his oil painting technique and absorbing the lessons of light, shadow, and intimate observation that would become hallmarks of his mature style. His affinity for their work led to his later nickname, "The American Rembrandt."

His final European stop was Paris in 1855. He briefly studied with the academic painter Thomas Couture, whose atelier attracted many international students, including Édouard Manet around the same time. While his time with Couture was short – cut off by the news of his mother's death, prompting his return to the United States – the exposure to the Parisian art world, with its competing currents of academicism and emerging realism (Gustave Courbet was a major force), further broadened his artistic perspective. He returned to America not just as a skilled portraitist, but as a painter equipped with sophisticated European techniques and a refined artistic vision.

Return to America: The Genre Painter Emerges

Upon his return to the United States in late 1855, Eastman Johnson initially spent time in Washington D.C. and Cincinnati before settling definitively in New York City by 1858. New York was rapidly becoming the undisputed center of the American art world, offering greater opportunities for exhibition, patronage, and interaction with fellow artists. Johnson established a studio and quickly began to make his mark, shifting his focus significantly from portraiture towards genre painting – scenes of everyday life.

The turning point came in 1859 with the exhibition of Negro Life at the South at the National Academy of Design's annual exhibition. The painting, later popularly retitled Old Kentucky Home (though depicting a scene observed in Washington, D.C.), was an immediate sensation. It portrayed a group of African Americans – enslaved and possibly free – in the dilapidated backyard of a house, engaged in various activities: music-making, courtship, relaxation, and quiet observation. The work's detailed realism, complex composition, and nuanced depiction of its subjects captivated audiences and critics alike.

Negro Life at the South generated considerable discussion and varied interpretations. Abolitionists saw in it the decay and inherent injustice of the slave system, pointing to the crumbling architecture and the figures' confinement. Pro-slavery advocates, conversely, sometimes interpreted it as an idyllic scene showcasing the supposed contentment and communal harmony of enslaved people. This ambiguity reflected the deeply divided national sentiment on the eve of the Civil War and cemented Johnson's reputation as an artist capable of tackling complex and sensitive contemporary themes with technical brilliance. The painting's success led to his election as an Associate of the National Academy of Design that same year, followed swiftly by his elevation to full Academician in 1860.

Depicting a Nation in Transition: Civil War and Beyond

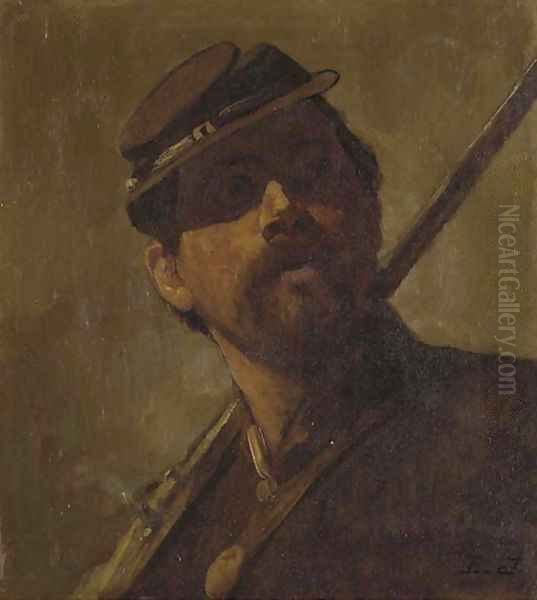

The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 profoundly impacted American society and, consequently, its art. Eastman Johnson, though not a soldier himself, engaged with the conflict through his work. He traveled with Union forces on several occasions, sketching soldiers and camp life. Unlike the grand, heroic battle scenes favored by some artists, Johnson often focused on the more personal, human aspects of the war and its effects.

One of his most powerful works from this period is A Ride for Liberty – The Fugitive Slaves (circa 1862). Based on an event he reportedly witnessed during the Manassas campaign, the painting depicts an African American family – a man, woman, and child – desperately galloping on horseback towards Union lines and freedom. The sense of urgency, fear, and hope is palpable, conveyed through the dynamic composition and the determined expressions of the figures. It stands as a poignant image of the struggle for emancipation during the war.

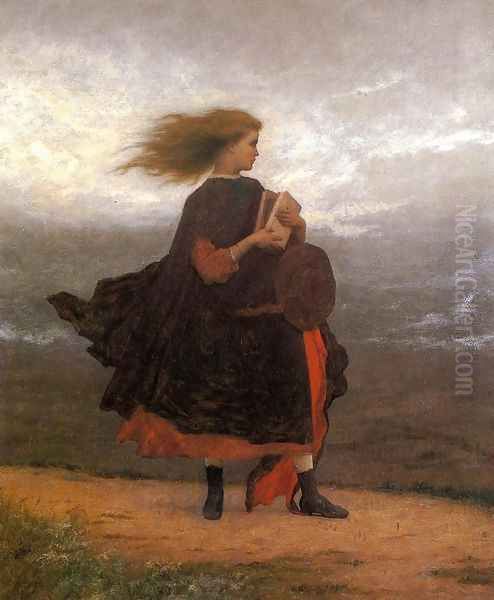

Other war-related works include The Wounded Drummer Boy (1863), showing a young soldier receiving care, and The Girl I Left Behind Me (circa 1870-75), a more reflective piece depicting a solitary young woman looking out a window, perhaps contemplating a loved one away at war or lost to it. These works emphasize the emotional toll and domestic impact of the conflict rather than battlefield glory, aligning with the intimate focus characteristic of his genre painting.

Following the war, Johnson continued to explore American life, but his focus gradually shifted away from the direct depiction of African American subjects, although they occasionally appeared in his later works. He increasingly turned his attention to rural life, particularly in New England. He spent considerable time in Maine and on the island of Nantucket, Massachusetts, capturing scenes that often evoked a sense of nostalgia for simpler, pre-industrial ways of life, a common theme in post-war American culture. He also traveled to the North Shore of Lake Superior, where he painted sympathetic portraits and scenes of the Ojibwe people.

Master of American Genre: Rural Life and Community

During the 1860s and 1870s, Eastman Johnson solidified his reputation as one of America's foremost genre painters, rivaled perhaps only by Winslow Homer in popularity and critical acclaim, though their styles differed significantly. Johnson excelled at depicting scenes of rural labor, community gatherings, and domestic interiors, often imbued with a warm, anecdotal quality. His European training, particularly the influence of Dutch and Flemish masters, is evident in his careful compositions, attention to detail, and masterful use of light, especially warm interior illumination.

His series depicting the process of maple sugaring in Maine, created during the 1860s, exemplifies this focus. Paintings like Maple Sugaring: The Camp show figures engaged in the communal activity of collecting sap and boiling it down, set within detailed woodland environments. These works celebrate rural traditions and the connection between community and landscape. Similarly, his Corn Husking Bee (circa 1876) captures the lively social atmosphere of a traditional agricultural gathering, filled with numerous figures interacting in a barn illuminated by lanterns, reminiscent of 17th-century Dutch barn interiors by artists like Adriaen van Ostade.

Perhaps his most celebrated late genre work is The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket (1880). This large, luminous painting depicts workers, primarily women and children, gathering cranberries in the expansive, sunlit fields of Nantucket. The painting is admired for its beautiful rendering of light and atmosphere, its detailed depiction of labor, and its evocation of a specific time and place. Unlike some genre paintings that could veer into sentimentality, Johnson's best works maintain a sense of dignity and realism, even when depicting picturesque subjects. Other notable genre scenes include The Old Stagecoach (1871), a nostalgic look at an earlier mode of transport filled with lively children, and various intimate interior scenes focusing on family life and childhood. These works resonated with a public seeking images that affirmed traditional values and community bonds during a time of rapid industrialization and social change.

The Portraitist of the Gilded Age

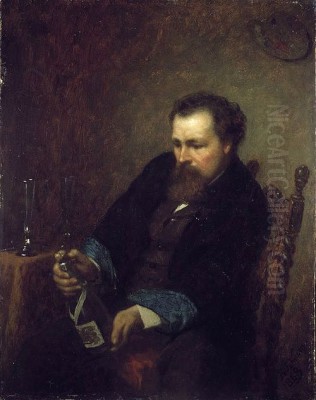

While Eastman Johnson achieved widespread fame through his genre paintings, portraiture remained a constant and increasingly important part of his practice, especially in the later decades of his career. As the Gilded Age progressed, with its accumulation of vast fortunes and the rise of a powerful new elite, the demand for formal portraits surged. Johnson, with his established reputation, technical skill, and ability to capture not just a likeness but a sense of presence and character, was perfectly positioned to meet this demand.

From the late 1870s onwards, portrait commissions began to dominate his output. This shift was likely driven by both financial considerations – portraits of prominent individuals were highly lucrative – and perhaps a change in artistic fashion or personal inclination. He painted many of the leading figures of the era, including presidents (Ulysses S. Grant, Chester A. Arthur, Grover Cleveland, Benjamin Harrison), powerful industrialists and financiers (Cornelius Vanderbilt, William H. Vanderbilt, Jay Gould), cultural leaders, and society figures.

His portrait style, refined through years of practice and informed by his study of masters like Rembrandt, was characterized by solid draftsmanship, a rich but often subdued color palette, and a focus on capturing the sitter's personality and psychological depth. He often employed strong chiaroscuro (contrast of light and dark) to model forms and create a sense of gravitas. While adhering to the conventions of formal portraiture expected by his clientele, his best portraits avoid stiffness and convey a sense of the individual's character and social standing. His success in this field further solidified his position within the highest echelons of the American art world. Notable contemporaries in American portraiture included John Singer Sargent, known for his dazzling brushwork, and Thomas Eakins, renowned for his uncompromising realism, providing different approaches against which Johnson's more traditional, yet insightful, style can be measured.

Artistic Style and Technique: The "American Rembrandt"

Eastman Johnson's artistic style is best characterized as a form of realism deeply informed by his academic training and his admiration for 17th-century Dutch painting. His nickname, "The American Rembrandt," while perhaps overly simplistic, points to a genuine affinity with the Dutch master's use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), his psychological insight in portraiture, and his interest in depicting everyday life with dignity. Johnson masterfully employed light not just for illumination but also to create mood, define form, and direct the viewer's eye, particularly in his warm, inviting interior scenes.

His draftsmanship was consistently strong, a skill honed during his early years creating crayon portraits. This underlying structure is evident even in his most painterly works. His compositions, especially in multi-figure genre scenes like Corn Husking Bee or Negro Life at the South, are carefully constructed, balancing numerous elements to create a cohesive and engaging narrative. He paid meticulous attention to detail – the texture of fabrics, the grain of wood, the specific features of individuals – which lends authenticity to his scenes.

Compared to his contemporary Winslow Homer, whose work often featured bolder compositions, more fluid brushwork, and a focus on the power of nature and outdoor light, Johnson's style was generally tighter, more detailed, and more focused on interior or communal scenes. While Homer often explored themes of human struggle against nature, Johnson typically focused on social interactions, labor, and domesticity. Unlike the stark, often unflinching realism of Thomas Eakins, Johnson's realism was usually tempered with a degree of warmth and sometimes sentiment, making his work highly accessible and popular with the public. His color palette tended towards rich earth tones, deep reds, and warm browns, contributing to the often cozy or nostalgic feel of his genre paintings.

Johnson's Circle and Institutional Roles

Beyond his individual artistic production, Eastman Johnson was an active participant in the burgeoning art institutions of New York City. His election as a full Academician to the National Academy of Design in 1860 was a significant recognition of his standing. The Academy was the premier art organization in the country at the time, holding influential annual exhibitions and operating an art school. Johnson remained involved with the NAD throughout his career, serving on its council and occasionally teaching.

Perhaps most significantly, Johnson was among the group of artists, patrons, and civic leaders who founded the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1870. This endeavor aimed to create a world-class art museum in New York, comparable to those in Europe. Johnson served on the museum's initial board of trustees and remained involved in its early years. His name is inscribed on the museum's facade, honoring his role as a founder. This involvement demonstrates his commitment to fostering a broader appreciation for art in America and building the cultural infrastructure of the nation.

Johnson was also a member of prominent social and cultural clubs frequented by artists, writers, and patrons, such as the Century Association and the Union League Club of New York. These affiliations placed him at the center of the city's cultural life, facilitating connections with potential clients and fellow artists. While detailed records of his day-to-day interactions with specific artists like Homer, Sargent, George Inness, or Worthington Whittredge might be sparse, his prominent position ensured he was a well-known figure within this milieu. His studio was a recognized fixture, and his participation in major exhibitions ensured his work was seen alongside that of his leading contemporaries.

Legacy and Influence: Chronicler of an Era

Eastman Johnson's legacy rests on his remarkable ability to capture the diverse facets of American life during a critical period of its history. He provided sensitive and insightful depictions of subjects ranging from the complexities of slavery and the impact of the Civil War to the communal rituals of rural life and the formal appearances of the Gilded Age elite. His work serves as an invaluable historical record, offering visual narratives of experiences and social dynamics often overlooked in written histories.

His influence extended to subsequent generations of American artists, particularly those working within the realist tradition. His commitment to depicting everyday American subjects helped validate genre painting as a significant field, paving the way for later artists who focused on American scenes, such as the Ashcan School painters like Robert Henri and John Sloan early in the 20th century, although their styles and urban focus differed greatly. His technical skill, particularly his handling of light and composition, provided a model for academic realists.

The nickname "The American Rembrandt" speaks to the high regard in which he was held, acknowledging his technical mastery and his ability to imbue ordinary scenes and portraits with emotional depth. While American art would evolve dramatically after his death with the advent of modernism, Johnson's work retained its appeal. His paintings continue to be studied for their artistic merit, their historical significance, and their nuanced portrayal of American identity. He remains a key figure for understanding the transition in American art from mid-century romanticism and the Hudson River School (exemplified by artists like Frederic Edwin Church or Albert Bierstadt) towards a more direct, yet often nostalgic, engagement with contemporary life.

Conclusion: A Lasting Vision

Jonathan Eastman Johnson carved a unique and enduring path through nineteenth-century American art. From his early, precise crayon portraits to his complex, evocative genre scenes and his dignified portrayals of Gilded Age leaders, his work consistently demonstrated technical brilliance and a keen observational eye. He navigated the influences of European tradition, particularly the Dutch Masters, while remaining deeply engaged with the specific realities and evolving identity of the United States.

His paintings, such as the controversial yet pivotal Negro Life at the South, the dynamic A Ride for Liberty, and the luminous The Cranberry Harvest, Island of Nantucket, are more than just depictions; they are complex documents reflecting the social, political, and cultural currents of his time. As a co-founder of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a respected member of the National Academy of Design, he also played a vital role in shaping the institutional landscape of American art. Eastman Johnson's legacy is that of a masterful painter and a crucial visual chronicler, whose art continues to offer rich insights into the American experience during a century of profound change.