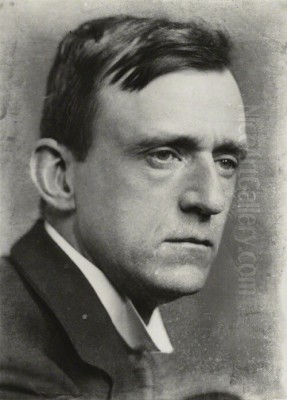

Henry Tonks stands as a unique and formidable figure in the annals of British art history, a man whose life and career were characterized by a remarkable duality. He was both a highly skilled surgeon and an influential artist and art educator, navigating these seemingly disparate worlds with exceptional proficiency. His legacy is etched not only in the delicate pastel portraits and incisive caricatures he created but also in the generations of artists he meticulously trained at the Slade School of Fine Art. Tonks's work during the First World War, documenting the harrowing facial injuries of soldiers, further cemented his place as an artist of profound human insight and technical brilliance, bridging the gap between scientific observation and artistic expression.

Early Life and Medical Aspirations

Born on April 9, 1862, in Solihull, Warwickshire, then a quiet town near Birmingham, Henry Tonks was the son of Edmund Tonks, a successful brass foundry owner, and Julia Johnson Tonks. His upbringing was comfortable, and he received his early education at the prestigious Clifton College in Bristol, a school known for its rigorous academic standards. It was here that the foundations of his disciplined mind were likely laid, though art was not yet his primary focus.

Following his schooling at Clifton, Tonks made the decision to pursue a career in medicine. He commenced his medical studies in Brighton between 1882 and 1886, later continuing at the London Hospital. He proved to be a dedicated and capable student, and in 1888, he achieved the significant milestone of qualifying as a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS), a testament to his surgical aptitude. This qualification opened doors for him in the medical profession, and he soon secured a position as a house surgeon at the London Hospital before moving to the Royal Free Hospital in London.

During his time at the Royal Free Hospital, Tonks not only practiced surgery but also began to share his knowledge. In 1892, he took on the role of teaching anatomy, a subject that would profoundly inform his later artistic practice. His deep understanding of human structure, gained through dissection and surgical experience, provided him with an invaluable foundation for his depiction of the human form in his art. Even as his medical career progressed, another passion was steadily growing within him.

The Irresistible Call of Art

While diligently pursuing his medical career, Henry Tonks cultivated a keen interest in drawing and painting. Initially, this was a private pursuit, a hobby that offered a creative outlet from the demanding world of surgery. However, the allure of art proved too strong to remain merely a pastime. His burgeoning talent and passion led him to seek formal instruction.

In 1887, Tonks enrolled in evening classes at the Westminster School of Art, studying under the influential artist and teacher Frederick Brown. Brown, who would later become the Slade Professor of Fine Art, recognized Tonks's exceptional potential and became a significant mentor. It was Brown who reportedly encouraged Tonks to consider art as a serious profession, even suggesting he might eventually abandon medicine entirely. This period at Westminster was crucial for Tonks, allowing him to hone his technical skills and immerse himself in an artistic environment.

Tonks's artistic development was rapid. He began exhibiting his work, and in 1891, he held his first solo exhibition, a significant step for any aspiring artist. His work started to gain recognition, and he became increasingly involved in the London art scene. He was a founding member of the New English Art Club (NEAC) in 1886, an exhibiting society established by artists who felt that the Royal Academy of Arts was too conservative and out of touch with contemporary artistic developments, particularly those emanating from France, such as Impressionism. The NEAC provided a vital platform for artists like Tonks, Walter Sickert, Philip Wilson Steer, and George Clausen to showcase their more progressive work.

By 1893, the pull of art had become irresistible. Henry Tonks made the momentous decision to largely abandon his promising medical career and dedicate himself more fully to painting and teaching art. While he never entirely relinquished his medical knowledge, which would prove vital later in his life, his primary focus shifted decisively towards the visual arts. This transition marked the beginning of a new, and arguably even more influential, chapter in his life.

The Slade Professor: Shaping a Generation

Henry Tonks's association with the Slade School of Fine Art, University College London, began in 1892, initially as an assistant to Professor Frederick Brown, his former mentor from Westminster. He was appointed to teach anatomy, a role for which his surgical background made him uniquely qualified. The Slade, at this time, was emerging as a leading art school in Britain, known for its emphasis on drawing from life and its relatively liberal atmosphere compared to the more rigid Royal Academy Schools.

Tonks quickly established himself as a formidable and highly respected, if somewhat feared, teacher. His teaching methods were rigorous and demanding, rooted in a profound understanding of draughtsmanship and the classical tradition. He insisted on meticulous observation and an unwavering commitment to technical skill. His critiques were known for their directness and, at times, their biting sarcasm, but they were invariably aimed at pushing his students to achieve their full potential. He famously championed the importance of "good drawing" above all else.

In 1918, Tonks succeeded Frederick Brown as the Slade Professor of Fine Art, a position he held with distinction until his retirement in 1930. Over his remarkable 38-year tenure at the Slade, he exerted an immense influence on several generations of British artists. His students included some of the most significant figures of early 20th-century British art, such as Stanley Spencer, Mark Gertler, Christopher R.W. Nevinson, William Roberts, Paul Nash, David Bomberg, Isaac Rosenberg, Gwen John, and Augustus John. While many of these artists would go on to embrace various forms of modernism, often diverging from Tonks's own more traditional aesthetic preferences, they all benefited from the rigorous grounding in drawing and composition he provided.

Tonks was somewhat conservative in his artistic tastes, famously wary of the more radical developments in modern art, such as Post-Impressionism, which he felt could lead students astray from fundamental principles. He encouraged his students to study the Old Masters and the great draughtsmen of the past. His emphasis on anatomical correctness and structural integrity in drawing had a lasting impact on British art education. Despite his traditional leanings, the Slade under his leadership fostered an environment where individual talent could flourish, producing artists of remarkable diversity and originality.

Artistic Style and Influences

Henry Tonks's artistic style is often characterized by its refined draughtsmanship, subtle use of color, and a quiet, introspective quality, particularly in his portraits and interior scenes. While he was a key figure in the New English Art Club, which championed Impressionist-influenced painting in Britain, Tonks's own work was not a straightforward adoption of French Impressionism. Instead, he developed a more personal style that synthesized various influences with his own distinct sensibility.

One of the most significant influences on Tonks was James McNeill Whistler. He admired Whistler's tonal harmonies, his elegant compositions, and his emphasis on the aesthetic qualities of painting. This influence can be seen in Tonks's delicate handling of light and atmosphere, and his preference for subtle gradations of color. Like Whistler, Tonks was interested in capturing the mood and character of his subjects rather than merely a literal likeness.

The French Impressionists, such as Edgar Degas, also left their mark on Tonks's work, particularly in his depiction of figures in interior spaces and his interest in capturing fleeting moments of everyday life. Degas's influence is evident in Tonks's compositional choices and his ability to convey a sense of intimacy and psychological depth. However, Tonks's approach was generally more restrained and less overtly experimental than that of many of his French contemporaries.

His deep knowledge of anatomy, honed through his medical training, was a constant underpinning of his art. This understanding allowed him to depict the human form with authority and conviction, even when his style was relatively loose or suggestive. He believed that good drawing was the foundation of all good art, and his own work exemplified this principle.

Tonks was also a keen observer of 18th and 19th-century British and French art. He admired artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres for his linear precision and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot for his lyrical landscapes and sensitive figure studies. His work often displays a quiet classicism, a sense of order and balance, even when depicting informal scenes. He was not an avant-garde revolutionary, but rather an artist who sought to build upon the best traditions of the past while developing his own distinctive voice.

Representative Works: A Glimpse into Tonks's World

Henry Tonks's oeuvre includes a range of subjects, but he is perhaps best known for his intimate interior scenes, often featuring women and children, his insightful portraits, and his later, deeply moving, wartime drawings.

One of his most celebrated early works is "The Torn Dress" (c. 1890-1900, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford). This painting depicts a young girl standing forlornly, her dress visibly torn, while an older woman, possibly her mother or governess, kneels to inspect the damage. The scene is rendered with great sensitivity, capturing the child's distress and the quiet domestic drama. The subtle play of light and the delicate brushwork are characteristic of Tonks's style.

Another notable painting is "A Girl with a Parrot" (c. 1898, location varies/private collections). This work, often featuring a young woman in an interior setting with a parrot, showcases Tonks's skill in capturing character and mood. The compositions are carefully balanced, and the interaction, or lack thereof, between the figure and the bird often creates a sense of quiet contemplation or gentle melancholy.

"An Evening in the Vale" (c. 1900, Tate Britain) depicts a group of figures, including children, in a softly lit interior, possibly engaged in a quiet evening activity. The painting evokes a sense of warmth and domesticity, with Tonks's characteristic attention to the nuances of light and shadow creating an intimate atmosphere. It reflects his interest in capturing the subtle dramas of everyday life.

"Rosamund and the Purple Jar" (c. 1900, Tate Britain) is another charming depiction of childhood, inspired by a moral tale by Maria Edgeworth. The painting shows a young girl, Rosamund, gazing wistfully at a chemist's shop window filled with colorful jars, having chosen a purple jar over a much-needed pair of shoes. Tonks captures the innocence and longing of the child with great tenderness.

His portraiture was also highly regarded. He painted many of his friends and colleagues, including a well-known portrait of the artist Philip Wilson Steer. These portraits are characterized by their psychological insight and their unpretentious, direct quality. He also produced a series of striking caricatures of his contemporaries, revealing a sharp wit and a keen eye for human foibles. These works, often executed in a looser, more expressive style, demonstrate another facet of his artistic personality.

The works mentioned, such as "The Rehearsal for the Soirée" (or "The Soirée," or "An Evening Rehearsal," c. 1900-1904, Tate), further exemplify his skill in depicting social interiors with a subtle narrative quality, often focusing on the interplay of figures within a carefully composed space. These paintings are not grand historical statements but rather quiet observations of human interaction and domestic life, rendered with technical finesse and emotional sensitivity.

The New English Art Club and Artistic Circles

The New English Art Club (NEAC), founded in 1885 and holding its first exhibition in 1886, played a pivotal role in Henry Tonks's artistic career and in the broader landscape of British art at the turn of the 20th century. Tonks was not only a founding member but also a central figure within the group for many years. The NEAC emerged as a vital alternative to the Royal Academy of Arts, which was perceived by many younger artists as insular and resistant to new artistic ideas, particularly those inspired by French Impressionism and Post-Impressionism.

The NEAC provided a platform for artists who were exploring new approaches to painting, emphasizing direct observation, plein air techniques, and a more modern sensibility. Tonks, alongside fellow artists such as Walter Sickert, Philip Wilson Steer, Frederick Brown, and George Clausen, helped to shape the direction and character of the club. These artists, while diverse in their individual styles, shared a commitment to artistic excellence and a desire to break free from the constraints of academic convention.

Tonks's involvement with the NEAC brought him into close contact with many of the leading artists of his day. He formed lasting friendships and professional relationships within this circle. His close friendship with Philip Wilson Steer, another influential figure at the Slade, was particularly significant. They often discussed art, shared ideas, and supported each other's work. The social and intellectual life of the NEAC was vibrant, with members gathering for dinners and discussions, creating a stimulating environment for artistic exchange.

Other notable artists associated with the NEAC during Tonks's active years included John Singer Sargent, who, although an established international figure, exhibited with the NEAC and shared some of its progressive aims. The club also attracted younger talents who would go on to become major figures in British art, many of whom were Tonks's own students from the Slade, such as Augustus John and William Orpen. The NEAC thus served as a bridge between established artists and emerging talents, fostering a dynamic and evolving artistic community.

Tonks's influence within the NEAC was considerable. He was respected for his artistic integrity, his critical judgment, and his unwavering commitment to the principles of good draughtsmanship. He served on the club's selection and hanging committees, helping to maintain its high standards and to promote the work of promising young artists. Through his active participation in the NEAC, Tonks played a crucial role in shaping the course of British art in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, championing a more modern and outward-looking approach to painting.

The Crucible of War: Art, Surgery, and Humanity

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 marked a profound turning point in Henry Tonks's life and career, compelling him to draw upon both his artistic skills and his dormant medical expertise in a unique and deeply impactful way. Despite having largely left his surgical career behind decades earlier, the unprecedented scale of casualties and the horrific nature of the new industrial warfare called him back to service.

In 1916, at the age of 54, Tonks was commissioned as a temporary lieutenant in the Royal Army Medical Corps (RAMC). He was initially sent to the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot. It was here that he began his extraordinary work documenting facial injuries, collaborating closely with the pioneering plastic surgeon Sir Harold Gillies. Gillies was at the forefront of developing new techniques for facial reconstruction, a field that was tragically burgeoning due to the devastating wounds inflicted by shrapnel, bullets, and burns.

Tonks was tasked with creating detailed pastel drawings of soldiers' faces before, during, and after surgical procedures. These were not mere medical illustrations; they were profoundly human documents. Working with pastels, a medium he handled with exceptional sensitivity, Tonks captured not only the physical trauma but also the psychological toll of these injuries. His drawings are remarkable for their clinical accuracy, their delicate rendering of damaged flesh and bone, and their empathetic portrayal of the sitters' vulnerability and resilience. He produced hundreds of these pastel studies, which became an invaluable part of the medical record and a testament to the human cost of war.

His collaboration with Gillies extended to the Queen's Hospital, Sidcup, which became a specialist center for facial and jaw injuries. Tonks's drawings served multiple purposes: they aided surgeons in planning reconstructive procedures, provided a record of the techniques being developed, and were used for teaching. Some of his illustrations were later included in Gillies's seminal textbook, "Plastic Surgery of the Face" (1920).

Beyond his work with Gillies, Tonks also served as an official war artist from 1918. In this capacity, he traveled to the Western Front in France, where he created works depicting scenes of war, including field dressing stations and the aftermath of battle. One notable painting from this period is "An Advanced Dressing Station in France, 1918" (Imperial War Museum), which conveys the grim reality of frontline medical care with a stark, unsentimental honesty.

Tonks's wartime art, particularly his facial injury portraits, stands as a unique contribution to the visual record of the First World War. These works blur the lines between art and medicine, science and humanity. They are often described as "anti-portraits" because they challenge conventional notions of portraiture by confronting the viewer with the brutal realities of disfigurement. Yet, in their unflinching gaze and compassionate rendering, they affirm the dignity and humanity of their subjects. This body of work remains a powerful and haunting reminder of the devastating impact of conflict. He also collaborated with the French illustrator Raphaël Freida in documenting these injuries, though their artistic styles differed, with Tonks's work often seen as more aligned with Impressionistic sensibilities and Freida's perhaps more narrative.

Caricatures and Social Commentary

Alongside his more formal portraits, interior scenes, and wartime drawings, Henry Tonks possessed a sharp wit and a keen eye for caricature, an aspect of his artistic output that reveals a different dimension of his personality and observational skills. His caricatures were often of his friends, colleagues, and prominent figures in the art world, and they display a humorous, sometimes satirical, but rarely malicious, insight into their characters and mannerisms.

These works were typically executed in a quicker, more spontaneous style than his paintings, often in pen and ink or watercolor. They demonstrate his mastery of line and his ability to capture a likeness and a personality with a few deft strokes. His subjects included fellow artists like Walter Sickert and Philip Wilson Steer, as well as art critics and other personalities of the day. These caricatures were often circulated privately among his circle, providing amusement and a lighthearted commentary on the art world's personalities.

Tonks's skill in caricature was not merely about exaggerated features; it was rooted in his deep understanding of human anatomy and his acute observation of posture, gesture, and expression. He could pinpoint the essential characteristics of a person and translate them into a vivid and often very funny visual statement. This ability to distill character into a few lines also informed his more serious portraiture, lending it a sense of psychological acuity.

Some historians note that his satirical impulse could also subtly infuse his more formal portraits, adding a layer of nuanced commentary. His understanding of human nature, sharpened by both his medical and artistic experiences, allowed him to perceive and depict the complexities and occasional absurdities of the people around him.

The tradition of caricature has a long and distinguished history in British art, with figures like William Hogarth, Thomas Rowlandson, and James Gillray setting a high standard. While Tonks's caricatures were generally more private and less overtly political than those of his 18th and early 19th-century predecessors, they share a similar incisiveness and a delight in the idiosyncrasies of human behavior. This facet of his work underscores his versatility as an artist and his engagement with the social and cultural milieu in which he lived and worked.

Later Years, Recognition, and Enduring Legacy

After his retirement from the Slade School of Fine Art in 1930, Henry Tonks continued to paint, though his output naturally lessened in his later years. He remained a respected figure in the British art world, his long career as both an artist and an educator having left an indelible mark. His contributions were formally recognized in various ways.

A significant honor came in 1936 when a major retrospective exhibition of his work was held at the prestigious Tate Gallery in London. This was a rare accolade for a living British artist at the time and a testament to the high regard in which he was held. The exhibition showcased the breadth of his artistic achievements, from his early interior scenes to his wartime drawings and later portraits.

Tonks's influence extended far beyond his own paintings. His impact as a teacher was profound and long-lasting. Many of his former students, who had gone on to become leading figures in British art, acknowledged the importance of his rigorous training and his unwavering commitment to the fundamentals of art. Artists like Stanley Spencer, despite developing a highly individual and visionary style, benefited greatly from the solid grounding in draughtsmanship they received from Tonks. The "Slade tradition" of strong drawing, which he championed, continued to influence British art education for many years.

His unique role during the First World War, documenting facial injuries, also contributed significantly to his legacy. These works, initially created for medical and historical purposes, have gained increasing recognition as powerful and important works of art in their own right. They offer a unique perspective on the human cost of war and the intersection of art and medicine. Exhibitions and publications in more recent decades have brought this aspect of his work to a wider public, highlighting its historical and artistic significance.

Henry Tonks passed away on January 8, 1937, in London, at the age of 74. His life had been one of extraordinary dedication to two demanding professions. He successfully navigated the worlds of medicine and art, bringing the discipline and observational skills of a surgeon to his artistic practice, and the sensitivity and insight of an artist to his understanding of the human condition. His letters and writings were later compiled, and a biography, "The Life of Henry Tonks" by Joseph Hone, was published in 1939, further documenting his remarkable life and contributions.

Conclusion: The Harmonious Duality of Henry Tonks

Henry Tonks remains a compelling and somewhat enigmatic figure in British art history. His career was a testament to the possibility of excelling in seemingly disparate fields, demonstrating that the precision of science and the expressiveness of art could not only coexist but also enrich one another. As a surgeon, he possessed a deep understanding of the human form; as an artist, he translated this knowledge into works of quiet beauty, psychological depth, and, in the case of his wartime drawings, profound pathos.

His tenure at the Slade School of Fine Art was transformative, shaping generations of British artists through his rigorous emphasis on draughtsmanship and anatomical understanding. While sometimes viewed as a conservative force in an era of burgeoning modernism, his dedication to fundamental skills provided a crucial foundation for many artists who would go on to explore diverse and innovative paths. His students, a veritable who's who of early 20th-century British art, including figures like Mark Gertler, C.R.W. Nevinson, Paul Nash, and Winifred Knights, carried his influence forward in myriad ways.

His involvement with the New English Art Club placed him at the heart of a movement that sought to revitalize British painting, engaging with contemporary European developments while forging a distinctly British modernism. His collaborations, whether with fellow artists like Philip Wilson Steer or medical pioneers like Sir Harold Gillies, underscore his ability to connect and contribute across different spheres.

Perhaps his most enduring and unique legacy lies in his poignant pastel drawings of facially injured soldiers from the First World War. These works transcend mere medical illustration, offering a compassionate and unflinching record of human suffering and resilience. They stand as a powerful testament to Tonks's ability to fuse his medical knowledge with his artistic sensitivity, creating images that continue to resonate deeply.

Henry Tonks's life and work offer a rich study in dedication, skill, and humanity. He was a master draughtsman, an influential teacher, and a compassionate observer of the human condition, leaving an indelible mark on both the art and, indirectly, the medical history of his time. His legacy is a reminder of the profound connections that can exist between seemingly separate disciplines and the enduring power of art to illuminate the human experience in all its complexity.