Archibald Standish Hartrick (1864-1950) stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in British art at the turn of the 20th century and beyond. A multifaceted artist, he distinguished himself as a painter, a pioneering lithographer, an insightful illustrator, and a dedicated art educator. Born in the colonial setting of Bombay, India, his artistic journey took him through the academic halls of London and the bohemian studios of Paris, where he brushed shoulders with some of the most revolutionary artists of his time, including Vincent van Gogh and Paul Gauguin. Hartrick's legacy is marked by his technical skill, his keen observation of life, and his commitment to portraying the human condition, particularly evident in his evocative wartime lithographs.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Archibald Standish Hartrick's life began far from the art capitals of Europe, in Bombay, India, in 1864. His early years were shaped by the colonial environment before his family relocated to Scotland. This move to the British Isles would prove pivotal for his future path. Initially, Hartrick pursued a career in medicine, enrolling at the University of Edinburgh. However, the allure of the visual arts proved stronger than the call of the medical profession.

His passion for art led him to abandon his medical studies and seek formal training. He made his way to London, the heart of the British art world, and enrolled in the prestigious Slade School of Fine Art. The Slade, under influential figures like Alphonse Legros, was a crucible for young talent, and Hartrick would have been exposed to rigorous academic training focused on drawing and anatomical accuracy. This foundational education would serve him well throughout his diverse artistic career. His contemporaries at or around the Slade period included artists who would also make their mark, such as Augustus John and William Orpen, though their styles would diverge.

Formative Years in Paris: Encounters with the Avant-Garde

Following his studies at the Slade, Hartrick, like many aspiring artists of his generation, was drawn to Paris. The French capital was the undisputed center of the art world in the late 19th century, a vibrant hub of innovation and artistic debate. It was here that Hartrick immersed himself in a dynamic environment, studying further and, crucially, forming connections that would deeply influence his perspective.

His time in Paris brought him into contact with seminal figures of Post-Impressionism. He notably befriended Vincent van Gogh, a relationship that Hartrick would later recount in his memoirs, providing valuable firsthand insights into the Dutch master's personality and working methods. He recalled Van Gogh working on a self-portrait in John Peter Russell's studio, a piece later found to be inscribed "Vincent, in friendship." This personal connection to Van Gogh, even before the latter's posthumous fame, highlights Hartrick's presence within significant artistic circles.

Beyond Van Gogh, Hartrick also knew Paul Gauguin, another towering figure of the era, whose bold use of color and departure from naturalism were revolutionizing painting. He also mentioned an acquaintance with an artist named Thomas Duchamp, a less commonly cited figure compared to his more famous near-contemporary Marcel Duchamp, but indicative of the breadth of his Parisian network. These encounters exposed Hartrick to radical new approaches to art, challenging traditional conventions and undoubtedly broadening his artistic horizons. He also developed an interest in Japanese art forms like chirimen (crepe paper prints), a fascination shared with Van Gogh and many other artists of the period, including Édouile Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard, who were influenced by Japonisme.

A Master of Lithography

While Hartrick was proficient in painting and drawing, it was in the field of lithography that he made some of his most enduring contributions. He became a highly skilled practitioner of this printmaking technique, known for the quality and artistic merit of his lithographs. At a time when lithography was often seen more as a commercial reproductive process, Hartrick was among those who championed its potential as a fine art medium.

He was a founding member of The Senefelder Club, established in London in 1908 to promote artistic lithography. Named after Alois Senefelder, the inventor of the process, the club included other prominent printmakers like Joseph Pennell and aimed to elevate the status of lithography. Hartrick's involvement underscored his commitment to the medium and his role as a pioneer in its revival in Britain. His technical expertise allowed him to explore the rich tonal possibilities of lithography, from delicate lines to deep, velvety blacks.

His mastery is perhaps best exemplified in his series Women's Work (1917), created during the First World War. These lithographs documented the vital roles women played on the home front, particularly in munitions factories. Works like On the Shell Tins, Women's Work in the War. On the Land: The 'Slackers', and The Munition Worker's Canteen are powerful and empathetic portrayals of women engaged in demanding and often dangerous labor. These prints are not only artistically accomplished but also serve as important historical documents.

Illustrative Work and Other Ventures

Hartrick's artistic talents also found an outlet in illustration. He contributed to various publications, bringing texts to life with his observational skills and draughtsmanship. One of his notable illustrative projects was for Rudyard Kipling's The Jungle Book. While perhaps not the primary field for which he is remembered, his work in illustration demonstrates his versatility and his ability to adapt his style to different narrative contexts.

During his earlier career, he also worked for the Daily Graphic, an illustrated newspaper. This experience, shared with friends and fellow artists like Frank Dean and E.J. Sullivan, would have honed his ability to work quickly and capture scenes effectively, skills valuable for both illustration and reportage. E.J. Sullivan, a renowned illustrator himself, even proposed Hartrick for membership in the Chelsea Arts Club, indicating his standing among his peers. His work also appeared in The Yellow Book, a leading avant-garde literary and art journal of the 1890s, placing him within the currents of the Aesthetic and Decadent movements, alongside artists like Aubrey Beardsley, though Hartrick's style was generally more traditional.

Hartrick the Educator

Beyond his own artistic practice, Archibald Standish Hartrick was a dedicated and influential art educator. He served as a painting instructor at the Camberwell School of Arts and Crafts in London, a role in which he could impart his knowledge and principles to a new generation of artists. His approach to teaching was thoughtful and grounded in his own experiences and observations.

This pedagogical commitment is further evidenced by his book, Drawing: From its Educational Power to its Emotional Expression. In this publication, Hartrick articulated his philosophy of art education, emphasizing the importance of keen observation and the training of touch as fundamental to drawing. He believed that art education should cultivate not just technical skill but also understanding and the ability to coordinate hand and eye to express emotion and perception authentically. He advocated for artists to draw what they truly saw, rather than relying on preconceived notions or formulas, a principle that resonated with the realism underpinning much of his own work. His teaching would have influenced numerous students, contributing to the broader landscape of British art education.

Personal Life and Artistic Circle

Archibald Standish Hartrick's personal life was intertwined with his artistic pursuits. He was married to Lily Blatherwick (1854-1934), herself a talented painter. Lily, also known as Mrs. A.S. Hartrick, exhibited her work and was part of the artistic community. Hartrick proudly recounted an anecdote where the eminent portraitist John Singer Sargent praised one of Lily's paintings, comparing its qualities to the work of Paul Cézanne – high praise indeed, linking her work to one of the foundational figures of modern art.

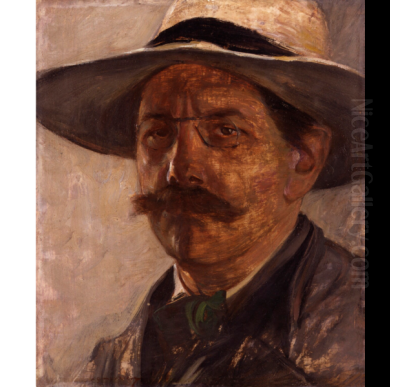

His friendships extended beyond his Parisian acquaintances. In London, he shared lodgings and a close camaraderie with Frank Dean and E.J. Sullivan. These relationships provided mutual support and intellectual exchange, common in artistic circles. His connection with Van Gogh, though perhaps brief in the grand scheme of their lives, left a lasting impression, with Hartrick creating a poignant portrait of Van Gogh from memory many years later, around 1913. This act of remembrance speaks to the significance of their encounter. He also recorded his interactions with Paul Gauguin, providing valuable, if personal, accounts of these artists' lives and characters.

Artistic Style and Philosophy

Hartrick's artistic style was characterized by a strong foundation in draughtsmanship, a keen eye for detail, and a commitment to realism, albeit a realism infused with personal observation and empathy. His portraits, such as the one of Van Gogh, are noted for their quick, precise lines that capture the sitter's character. In his lithographs, particularly the Women's Work series, he demonstrated an ability to convey the atmosphere of a scene and the humanity of his subjects.

His philosophy, as expressed in his teaching and writings, emphasized the importance of visual truth. He encouraged artists to trust their own eyes and to depict the world as they experienced it. This did not necessarily mean a photographic reproduction of reality, but rather an authentic response to the visual world, filtered through the artist's sensibility. While he was exposed to the radical experiments of Post-Impressionism and other avant-garde movements in Paris, his own work largely retained a more representational approach, focusing on capturing the essence of his subjects and their environments. His interest in social themes, as seen in his wartime art, also suggests a belief in art's capacity to comment on and record human experience. He often sought to convey deeper meaning and value, sometimes deviating from conventional forms to achieve this.

Wartime Contributions: Documenting Women's Roles

The First World War provided a significant, if somber, context for Hartrick's work. He was officially commissioned as a war artist, a role that saw many artists, such as Paul Nash, C.R.W. Nevinson, and Muirhead Bone, create powerful records of the conflict. Hartrick's specific focus, however, was unique and historically important: he was tasked with documenting the work of the Women's Land Army and women in munitions factories.

His series of lithographs, Women's Work, stands as a crucial visual record of the immense contribution women made to the war effort on the home front. These images depicted women undertaking physically demanding and often perilous jobs previously considered the domain of men. Hartrick approached these subjects with sensitivity and respect, capturing not only the labor itself but also the spirit and resilience of the women. He was reportedly the first artist to be commissioned to record the work of the Women's Land Army. These works are invaluable for their social historical content, reflecting a shift in societal roles and perceptions of women's capabilities during a period of profound upheaval. His art in this period transcended mere documentation, offering an empathetic portrayal of a transformative moment in social history.

Reception and Legacy

During his lifetime, Archibald Standish Hartrick achieved a degree of recognition, particularly for his lithographs and his role in The Senefelder Club. He exhibited his work and was respected as an educator. However, he may not have achieved the same level of widespread fame as some of his more revolutionary Parisian contemporaries like Van Gogh or Gauguin, or even some of his British peers such as Walter Sickert or Philip Wilson Steer, who were prominent in the New English Art Club.

Some contemporary assessments, such as a comment regarding his work in The Yellow Book Volume VI, suggested his contributions could seem "ordinary" when placed alongside more flamboyant or experimental pieces. This likely refers to a general critique by Henry Harland (writing as "The Yellow Dwarf") about the state of British book reviewing, rather than a specific slight against Hartrick, but it indicates the competitive and critical environment of the time.

However, Hartrick's legacy has endured and, in many respects, grown in appreciation. His firsthand accounts of Van Gogh and Gauguin are valuable historical resources for art historians. His book on drawing offers insights into art education philosophies of the period. Most significantly, his lithographs, especially the Women's Work series, are now recognized for their artistic quality and their importance as social documents. They are held in major collections, including the Imperial War Museum and the British Museum, and are frequently studied for their depiction of women's roles during WWI. His dedication to the art of lithography also contributed to its acceptance and development as a fine art medium in Britain.

Conclusion: A Quietly Influential Force

Archibald Standish Hartrick's career was one of quiet dedication, technical skill, and insightful observation. From his early training at the Slade to his formative experiences in Paris alongside giants of modern art, and through his mature work as a lithographer, illustrator, and educator, he consistently demonstrated a commitment to artistic integrity. While he may not have sought the spotlight in the same way as some of his contemporaries, his contributions to British art are undeniable.

His sensitive portrayal of wartime women's labor, his advocacy for lithography, and his thoughtful approach to art education have secured his place in art history. Hartrick's work serves as a reminder that artistic significance can be found not only in radical innovation but also in the skillful and empathetic depiction of the human experience and the steadfast championing of artistic craft. His life and art offer a fascinating window into the artistic currents that flowed between London and Paris at a pivotal moment in the history of modern art, and his legacy continues to be appreciated for its depth, skill, and humanity. Artists like Spencer Gore or Harold Gilman of the Camden Town Group also explored everyday British life, and Hartrick's work, particularly his observational drawings and prints, shares some of this commitment to depicting contemporary reality.