Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins stands as one of the most significant and complex figures in the history of American art. Born in Philadelphia on July 25, 1844, and dying in the same city on June 25, 1916, Eakins dedicated his life to the pursuit of an unflinching realism, grounded in scientific observation and a deep understanding of the human form. He was a painter, photographer, sculptor, and influential teacher whose work captured the intellectual, social, and physical life of his native Philadelphia with an intensity that often challenged the conventions of his time. His legacy is one of profound artistic achievement, pedagogical innovation, and enduring controversy.

Early Life and European Training

Eakins grew up in Philadelphia, a city that would remain his lifelong home and primary subject. His father, Benjamin Eakins, was a writing master and calligrapher, fostering an environment where precision and skill were valued. Thomas attended the prestigious Central High School, known for its strong emphasis on science and technical drawing, which undoubtedly shaped his later artistic approach. He demonstrated early artistic talent and enrolled in classes at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) from 1862 to 1866, studying drawing and anatomy.

Seeking more advanced training, Eakins traveled to Paris in 1866, enrolling at the École des Beaux-Arts. There, he studied under the acclaimed academic painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his meticulous technique and historical subjects. He also received instruction from the portraitist Léon Bonnat and the sculptor Augustin-Alexandre Dumont. Unlike many American artists who absorbed French Impressionism, Eakins gravitated towards the rigorous draftsmanship and anatomical precision emphasized by his teachers, though he would apply these skills to distinctly American subjects.

A pivotal trip to Spain in 1869 exposed Eakins to the works of Spanish masters like Diego Velázquez and Jusepe de Ribera. Their powerful realism, dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro), and unidealized depiction of human subjects deeply impressed him. This experience reinforced his commitment to portraying the world as he saw it, without romantic embellishment, a path diverging from the more polished style of Gérôme and the burgeoning Impressionist movement led by artists like Claude Monet and Edgar Degas back in France.

Return to Philadelphia and the Rise of Realism

Upon returning to Philadelphia in 1870, Eakins set out to establish himself as an artist committed to depicting contemporary American life. He rejected the idealized landscapes of the Hudson River School painters like Albert Bierstadt and the sentimental genre scenes popular at the time. Instead, he turned his sharp, analytical eye to the world around him: the athletes, scientists, musicians, and intellectuals of his city.

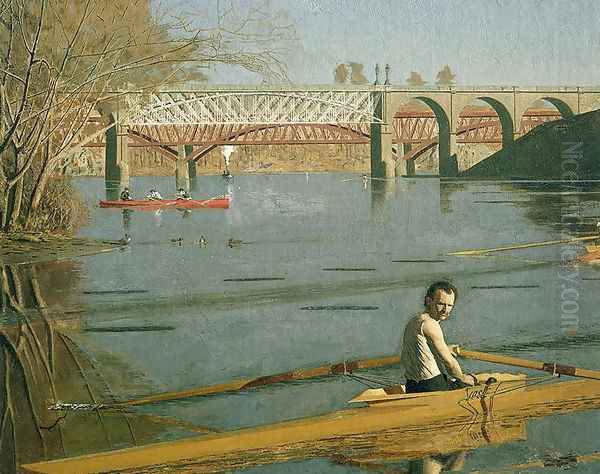

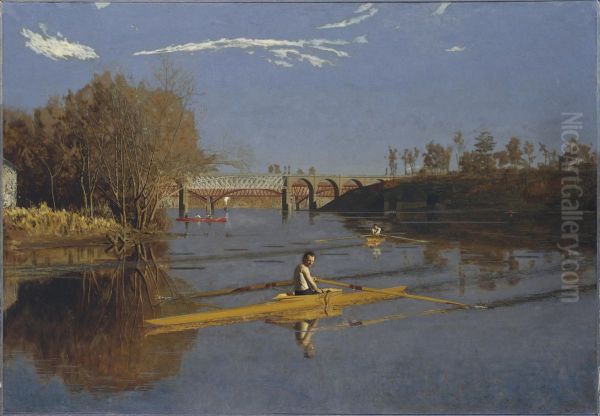

His early masterpieces often focused on outdoor activities, particularly rowing on the Schuylkill River. Works like Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (1871) and The Champion Single Sculls (1871) are remarkable for their precise rendering of light on water, the physical exertion of the rowers, and the specific details of the boats and the Philadelphia landscape in the background. These paintings demonstrate Eakins's early mastery of perspective, anatomy, and the depiction of figures in motion within a specific, identifiable environment. They were a declaration of his realist intent.

Eakins approached these subjects with an almost scientific rigor. He made numerous preparatory sketches, studied the mechanics of rowing, and even built scale models to understand the play of light and reflection. This methodical process, combining direct observation with analytical study, became characteristic of his work throughout his career. He sought not just resemblance, but a deeper truth rooted in the physical reality of the subject.

The Scientific Eye: Anatomy and Medicine

Eakins's interest in science, particularly human anatomy, was fundamental to his art. He believed that a thorough understanding of the body's structure was essential for realistic depiction. He attended lectures and dissections at Jefferson Medical College, developing a profound knowledge that surpassed that of most artists of his day. This anatomical expertise became central to his teaching and informed some of his most famous and controversial works.

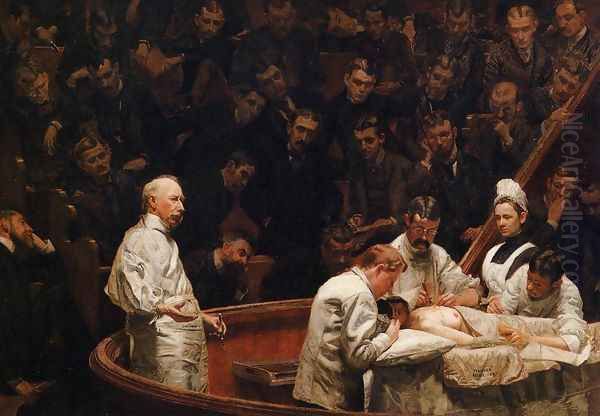

In 1875, Eakins completed Portrait of Dr. Samuel D. Gross (The Gross Clinic). This monumental painting depicts the renowned Philadelphia surgeon Dr. Gross presiding over an operation in an amphitheater at Jefferson Medical College. The work is a startlingly realistic portrayal of 19th-century surgery, complete with blood, surgical instruments, and intense concentration on the faces of the participants. Eakins included himself in the painting, sketching in the background, asserting his role as an objective observer.

The Gross Clinic was submitted to the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia but was rejected by the art jury for its graphic subject matter, deemed inappropriate for display in the art hall. It was eventually shown in the medical section. The painting's uncompromising realism shocked many viewers accustomed to more idealized art, but its power, technical brilliance, and psychological intensity were undeniable. Today, it is considered one of the greatest American paintings ever created.

Fourteen years later, in 1889, Eakins painted The Agnew Clinic, depicting another prominent surgeon, Dr. David Hayes Agnew, performing a mastectomy. While still realistic, this work is brighter and perhaps less brutally graphic than The Gross Clinic. It shows Agnew lecturing to students in a cleaner, more modern surgical environment. Commissioned by Agnew's students, it further cemented Eakins's reputation as a master of medical and scientific portraiture, though it too faced criticism for its realism.

Master of Portraiture

Beyond the large-scale medical scenes, Eakins was a prolific and insightful portrait painter. He approached portraiture with the same commitment to realism and psychological depth. He eschewed flattery and conventional poses, seeking instead to capture the sitter's individual character and intellectual presence. His portraits are often somber, introspective, and intensely focused on the subject's inner life.

Eakins painted prominent figures from Philadelphia's cultural and scientific communities, including scientists, artists, musicians, and clergy. He also frequently painted friends and family members. His subjects often appear lost in thought, their expressions conveying a sense of gravity and experience. He used strong contrasts of light and shadow, reminiscent of Rembrandt, to model form and enhance the psychological mood.

His portrait of the poet Walt Whitman (1887-1888) is a notable example. Whitman, who admired Eakins's directness, reportedly said of the portrait, "Eakins is not a painter, he is a force." The work captures the aged poet's ruggedness and intellectual intensity without sentimentality. Other significant portraits include those of his wife, the artist Susan Macdowell Eakins, his father Benjamin Eakins, and fellow artists like William Merritt Chase (though Chase reportedly disliked his portrait). Compared to the elegant, often society-focused portraits by contemporaries like John Singer Sargent or James McNeill Whistler, Eakins's work feels more grounded, probing, and psychologically complex.

Capturing Motion: Photography and Art

Eakins was a pioneer in the use of photography as a tool for artistic study, particularly in analyzing human and animal motion. In the 1880s, working alongside or in parallel with Eadweard Muybridge, who was also conducting photographic motion studies at the University of Pennsylvania, Eakins developed his own techniques using multiple exposures to capture sequential movements on a single photographic plate.

He saw photography not as a replacement for painting but as a valuable aid to understanding the reality of movement, which happened too quickly for the unaided eye to perceive accurately. His photographic studies of athletes running, jumping, and boxing, as well as animals in motion, informed the anatomical accuracy and dynamic poses in his paintings and sculptures.

This integration of photography into the artistic process was innovative and forward-thinking. While some traditionalists criticized the use of mechanical aids, Eakins embraced the camera as another tool, alongside anatomical study and direct observation, in his quest for truth. His photographic work, though primarily intended as studies, is now recognized for its own artistic and historical significance, anticipating aspects of modern photography and cinema. Works like A May Morning in the Park (The Fairman Rogers Four-in-Hand) (1879-80) benefited directly from his photographic research into the gait of horses.

Eakins the Educator

Eakins's dedication to realism extended to his influential role as an educator. He began teaching at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts (PAFA) in 1876, eventually becoming its director in 1882. His teaching methods were radical for the time. He emphasized working directly from the live nude model, insisted on rigorous anatomical study (including dissections, which he encouraged students to attend), and incorporated photography and perspective studies into the curriculum.

He believed that students should understand the underlying structure of the human body to depict it accurately. He famously discarded the academy's collection of plaster casts of antique sculptures, insisting that students learn from life itself. His demanding, science-based approach attracted devoted students who admired his integrity and commitment to truth.

Among his notable students were Thomas Anshutz, who succeeded him at PAFA and taught future members of the Ashcan School; Henry Ossawa Tanner, one of the first internationally acclaimed African American artists; and the sculptor Samuel Murray, who became a close friend and collaborator. Eakins's influence extended through his students to subsequent generations of American artists, particularly those committed to realism and depicting contemporary urban life, such as Robert Henri, John Sloan, George Luks, and Everett Shinn, all of whom studied under Anshutz.

Controversy and Dismissal

Eakins's uncompromising methods and personality inevitably led to conflict. His insistence on the use of fully nude models, for both male and female students, clashed sharply with Victorian-era sensibilities regarding propriety. While Eakins saw nudity as essential for anatomical understanding, many found his approach shocking and inappropriate.

The breaking point came in 1886. During a lecture to a class that may have included female students (accounts vary), Eakins removed the loincloth from a male model to demonstrate a point about pelvic anatomy. This incident caused an uproar among some students and the PAFA board of directors. Faced with mounting criticism and accusations of misconduct, Eakins was forced to resign.

His dismissal was a major scandal and a significant blow to his career. Many of his students resigned in protest and formed the Art Students' League of Philadelphia, where Eakins continued to teach briefly. The controversy, however, solidified his reputation in some circles as a difficult and morally questionable figure. In later years, more serious accusations of psychological and possibly physical abuse towards family members and models have surfaced, particularly through the research of biographer Henry Adams, adding further complexity and darkness to his personal legacy, though these remain subjects of debate among scholars.

Later Life and Work

After his dismissal from PAFA, Eakins continued to paint, focusing increasingly on portraiture. Commissions became scarcer, partly due to his reputation and his refusal to flatter sitters. He often painted friends, family, scientists, and fellow artists who appreciated his unvarnished approach. His later portraits possess a profound sense of psychological weight and introspection, perhaps reflecting his own experiences of professional isolation and societal disapproval.

During this period, he also created some of his most iconic works depicting sports and the human form. The Swimming Hole (1884-1885), painted just before his dismissal, shows Eakins himself and several students swimming nude in a pastoral setting. It is a celebration of the male form and camaraderie, rendered with classical compositional structure but grounded in realistic observation. It has also been interpreted as an exploration of male relationships and homoerotic undertones, reflecting modern scholarly interest in Eakins's complex relationship with the body and sexuality.

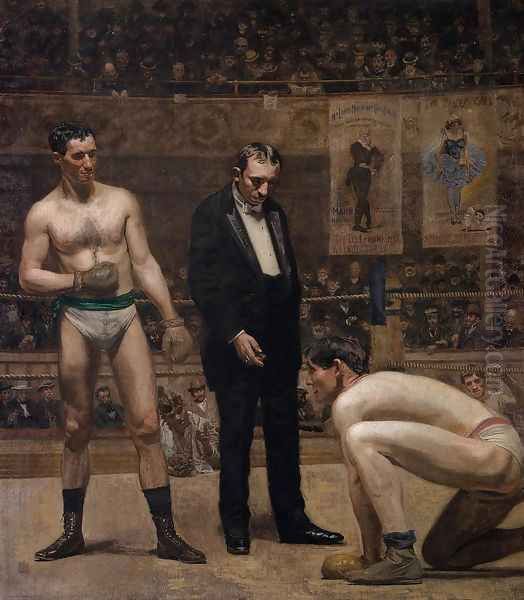

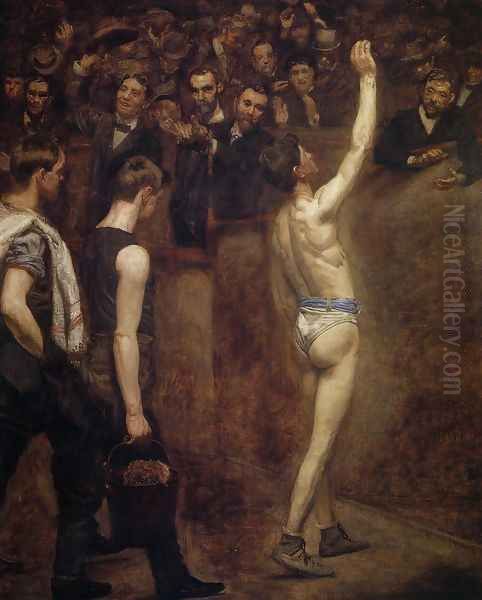

He also painted several powerful boxing scenes, such as Taking the Count (1896) and Salutat (1898), which capture the brutal energy and drama of the sport with intense realism. Additionally, Eakins produced significant work in sculpture, often focusing on anatomical accuracy, including reliefs for the Trenton Battle Monument and figures of prophets for the Witherspoon Building in Philadelphia. His wife, Susan Macdowell Eakins, a talented painter in her own right who had been his student, remained a steadfast supporter throughout his later years, managing his career and promoting his work after his death.

Artistic Style and Philosophy

Thomas Eakins's art is defined by its rigorous realism, scientific objectivity, and psychological depth. He believed that beauty and truth were found in the accurate depiction of the observable world, particularly the human form. His style is characterized by:

Anatomical Accuracy: A profound understanding of human and animal anatomy underlies all his figures.

Scientific Observation: He employed careful study, perspective analysis, and photographic aids to achieve realism.

Unflinching Honesty: Eakins refused to idealize or sentimentalize his subjects, whether depicting surgery, athletics, or portrait sitters.

Mastery of Light and Form: He used light and shadow effectively to model three-dimensional form and create dramatic or introspective moods, often drawing inspiration from masters like Rembrandt and Velázquez.

Psychological Insight: His portraits, in particular, delve beneath the surface to reveal the character and inner life of the individual.

Focus on American Life: His subjects were drawn from his immediate environment – the people, activities, and intellectual life of Philadelphia.

His approach stood in contrast to the prevailing trends of his time, such as the decorative elegance of American Impressionism (practiced by artists like Childe Hassam) or the visionary symbolism of painters like Albert Pinkham Ryder. Eakins carved a unique path, committed to a realism that was both intellectually rigorous and deeply human.

Contemporaries and Context

Eakins worked during a dynamic period in American art. While he remained largely based in Philadelphia, his career intersected with major national and international developments. He was a contemporary of Winslow Homer, another giant of American realism, though Homer focused more on nature, the sea, and narrative genre scenes, often with a more heroic or elemental feel.

Other contemporaries included the expatriate painters James McNeill Whistler and John Singer Sargent, whose cosmopolitan styles and focus on aesthetic effects differed greatly from Eakins's grounded realism. Mary Cassatt, another Philadelphia native who studied briefly at PAFA before finding fame in Paris as an Impressionist alongside Degas, represents a contrasting artistic direction.

Eakins's influence was most directly felt through his students, particularly Thomas Anshutz, who carried forward aspects of his realist teaching. Anshutz, in turn, taught key figures of the Ashcan School – Robert Henri, John Sloan, George Luks, Everett Shinn, and William Glackens – who depicted gritty urban life in the early 20th century. While their style was often looser and more painterly than Eakins's, their commitment to portraying contemporary American reality owes a debt to his pioneering work.

Legacy and Reappraisal

During his lifetime, Thomas Eakins achieved recognition within certain circles but never widespread fame or financial success. His uncompromising realism and controversial teaching methods often alienated potential patrons and the art establishment. However, following his death in 1916, his reputation began to grow steadily.

A major memorial exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1917 helped bring his work to greater public attention. Throughout the 20th century, critics and art historians increasingly recognized him as a pivotal figure in American art – perhaps the most profound and powerful realist the nation had produced. His major works, particularly The Gross Clinic, The Agnew Clinic, Max Schmitt in a Single Scull, and The Swimming Hole, are now considered icons of American painting.

Today, Eakins is celebrated for his technical mastery, his psychological insight, and his unflinching dedication to truth. His integration of science and art, his pioneering use of photography, and his influential teaching methods are all acknowledged as significant contributions. His works are held in major museums across the United States, including the Philadelphia Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the National Gallery of Art.

His legacy is not without complexity. Ongoing discussions about his controversial teaching practices, his difficult personality, and the interpretations of his personal life continue to shape our understanding of the man and his art. Yet, Thomas Eakins remains an essential figure, an artist whose intense, uncompromising vision captured the character of his time and place with enduring power and relevance. He set a standard for realism and psychological depth that continues to challenge and inspire artists today.