Introduction: An Artist Between Eras

Kobayashi Kiyochika stands as a pivotal figure in the history of Japanese art, an artist whose life and work bridged the final years of the feudal Edo period and the rapid, often tumultuous, modernization of the Meiji era. Born in the heart of Edo (later Tokyo) just as Japan began its profound transformation, Kiyochika became renowned not only as the last significant master of the traditional ukiyo-e woodblock print but also as a crucial innovator who incorporated Western artistic techniques to capture the changing face of his nation. His unique style, particularly his exploration of light and shadow, earned his works the name kōsen-ga (light pictures), distinguishing him from his predecessors and contemporaries. Through his landscapes, satirical cartoons, and war prints, Kiyochika provided an invaluable visual record of Japan's dramatic entry into the modern world.

The Dawn of a New Era: Meiji Japan's Transformation

To understand Kobayashi Kiyochika's art, one must first appreciate the context of his time. He was born in 1847, a mere few years before Commodore Perry's arrival forced Japan to open its ports to the West, ending centuries of self-imposed isolation. The subsequent Meiji Restoration in 1868 overthrew the Tokugawa Shogunate, restored imperial rule, and initiated an era of intense modernization and Westernization under the slogan Bunmei Kaika ("Civilization and Enlightenment"). This period saw the dismantling of the feudal system, the decline of the samurai class, the introduction of Western technology like railways, steamships, and gas lighting, and a fundamental shift in Japanese society, culture, and aesthetics. Tokyo, the renamed Edo, became the epicenter of this change, a city rapidly shedding its past and embracing a new, often uncertain, future. This dynamic, sometimes jarring, transition became the primary subject of Kiyochika's most celebrated works.

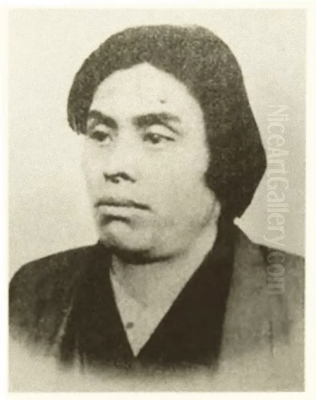

Early Life: From Samurai Scion to Aspiring Artist

Kobayashi Kiyochika was born on September 10, 1847, in the Honjo district of Edo. He was the ninth child of Kobayashi Mohei, a minor samurai official responsible for overseeing rice granaries for the Tokugawa Shogunate. His family belonged to the lower echelons of the samurai class, a group particularly vulnerable to the societal shifts underway. The death of his father just before the Meiji Restoration further destabilized the family's situation as the old feudal stipends disappeared. Following the collapse of the Shogunate, the young Kiyochika demonstrated loyalty by accompanying the last Shogun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, into exile in Shizuoka.

Life in Shizuoka was likely challenging. Sources suggest Kiyochika engaged in various occupations to survive during these formative years, possibly including stints as a wrestler's attendant, a fisherman, or even a traveling entertainer. These experiences outside the traditional confines of samurai life undoubtedly broadened his perspective and perhaps instilled in him a keen observational eye for the realities of everyday existence. He eventually returned to his transformed hometown, now called Tokyo, in 1874, determined to pursue a career in art, a path quite different from his samurai heritage.

Artistic Formation: A Synthesis of East and West

Kiyochika's artistic training was eclectic and largely self-directed, reflecting the transitional nature of the Meiji art world. While rooted in Japanese traditions, he actively sought out and absorbed Western influences. Early on, he is said to have received some instruction in traditional Japanese painting, potentially studying under artists associated with the Kano school, such as Kano Toshun. More significantly, he interacted with prominent figures like the famously eccentric painter Kawanabe Kyōsai and the master lacquer artist and painter Shibata Zeshin. While the exact nature of their tutelage is unclear, exposure to such accomplished artists would have provided a strong foundation in Japanese aesthetics and techniques.

However, Kiyochika's defining characteristic became his integration of Western methods. He reportedly studied Western-style painting and possibly photography while living near the foreign settlement in Yokohama. A key figure often cited as an influence, and perhaps a direct teacher, is the British artist and cartoonist Charles Wirgman. Wirgman, who resided in Yokohama and published the satirical magazine Japan Punch, was instrumental in introducing Western concepts like linear perspective, shading (chiaroscuro), and anatomical accuracy to Japanese artists. Kiyochika masterfully adapted these elements, particularly the dramatic use of light and shadow, into the woodblock print medium, which traditionally favored flat planes of color and strong outlines.

Kōsen-ga: Painting with Light and Shadow

Kiyochika's innovative approach culminated in the development of kōsen-ga, or "light pictures." This style, which characterized his landscape prints from the mid-1870s to the early 1880s, marked a significant departure from traditional ukiyo-e. While earlier masters like Utagawa Hiroshige had depicted weather and time of day, Kiyochika focused intensely on the effects of light itself – the glow of gas lamps on wet streets, the silhouette of bridges against a fiery sunset, the subtle gradations of moonlight, the hazy atmosphere of a foggy afternoon.

He employed Western perspective to create a sense of depth and realism previously uncommon in ukiyo-e landscapes. More importantly, he utilized sophisticated shading and color gradation, achieved through meticulous carving and printing techniques, to model forms and evoke specific atmospheric conditions and moods. His prints often possess a quiet, melancholic, or dramatic intensity, capturing not just the physical appearance of Meiji Tokyo but also its psychological atmosphere – a city caught between tradition and modernity, light and shadow. This focus on naturalistic light and atmospheric effects was revolutionary for the woodblock medium.

Views of Tokyo (Tōkyō Meisho Zu): A City in Flux

Kiyochika's most famous and enduring contribution is the series Views of Tokyo (Tōkyō Meisho Zu), produced primarily between 1876 and 1881. Comprising 93 known prints, this series offers an unparalleled visual chronicle of the city during its most transformative period. Kiyochika depicted both the remnants of old Edo and the symbols of the new Meiji era, often juxtaposing them within the same scene. Famous landmarks like the Ryōgoku Bridge or temples were shown alongside new Western-style brick buildings, railway lines, steamships puffing smoke on the Sumida River, telegraph poles, and the ubiquitous gas lamps that were altering the city's nocturnal landscape.

Prints like Fireflies at Ochanomizu or Moonlight Night at Miyajima (though technically outside Tokyo, often associated with his style) showcase his mastery of subtle nocturnal light, while View of Takanawa Ushimachi under a Shrouded Moon captures a sense of moody mystery. Others, like depictions of the Ginza after a fire, show the city rebuilding itself with Western architecture. The series was initially popular, tapping into the public's fascination with the changing cityscape. However, as the novelty wore off and perhaps as faster, cheaper printing methods like lithography gained traction, sales declined, and Kiyochika ceased producing landscape prints in this style after 1881 for a period. Despite this, Views of Tokyo remains a landmark achievement, admired for its artistic innovation and historical significance. Some scholars note that even Western artists like Vincent van Gogh, an avid collector of Japanese prints, owned works that showed Kiyochika's influence, demonstrating the reach of his vision.

Expanding Horizons: Satire and War Reportage

While best known for his landscapes, Kiyochika was a versatile artist who also worked extensively in other genres, notably satirical cartoons (ponchi-e, named after Wirgman's Japan Punch) and war prints (sensō-e). In the 1880s, facing declining sales for his landscapes, he turned increasingly to illustration and cartoons for popular magazines and newspapers. His satirical works often targeted political figures and commented on social trends and the absurdities of rapid Westernization.

His sharp wit and critical stance sometimes brought him into conflict with the authorities. During the era of the Freedom and People's Rights Movement (Jiyū Minken Undō), government censorship was strict. Kiyochika produced several prints that were deemed politically sensitive and subsequently banned. The provided source mentions two such examples related to the "Fukushima Incident" (a political uprising in 1882): Portrait of Mr. Hiraoka Kōtarō (likely referring to a figure involved) and Portrait of Mr. Tamono Hideaki. Creating such works demonstrated considerable courage, highlighting the artist's engagement with the pressing issues of his day.

With the outbreak of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895) and later the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), Kiyochika, like many ukiyo-e artists such as Tsukioka Yoshitoshi (though Yoshitoshi died in 1892, his influence on war prints was significant), turned to producing war prints. These prints served as a form of visual journalism and patriotic propaganda, depicting battles, heroic soldiers, and Japanese victories. Kiyochika produced hundreds of these often dramatic and brightly colored triptychs. While popular at the time, these works are viewed more critically today. They often relied on nationalistic fervor and presented stereotypical, sometimes dehumanizing, portrayals of enemy soldiers, particularly the Chinese. Nonetheless, they represent an important facet of Kiyochika's output and reflect the intense nationalism that characterized Meiji Japan during these conflicts.

Teaching and Influence: Passing the Torch

Despite his struggles, Kiyochika remained a respected figure in the Tokyo art world. In 1894, demonstrating his commitment to the future of Japanese art, he opened his own art school, the Kyōsai-juku, likely named in homage to his former associate Kawanabe Kyōsai. He took on students, passing on his skills and unique approach to printmaking.

His most notable student was Tsuchiya Kōitsu (not to be confused with the Western-style painter Tsuguharu Foujita). Kōitsu began studying with Kiyochika as a teenager and reportedly lived and worked in his household for some 19 years. Kōitsu absorbed his master's sensitivity to light and atmosphere, later becoming a significant artist in the shin-hanga (new prints) movement, known for his beautifully rendered landscapes that echo Kiyochika's pioneering kōsen-ga style.

Other artists, such as Inoue Yasuji (also known as Inoue Tankei) and Ogura Ryūson, worked in a style closely related to Kiyochika's kōsen-ga during the late 1870s and 1880s. While their exact relationship to Kiyochika as formal students is debated, their work clearly shows his influence, suggesting the formation of a distinct artistic circle or sensibility centered around his innovative approach to depicting the modern Tokyo landscape. Their prints, often focusing on similar subjects and employing comparable techniques for light and shadow, further cemented the kōsen-ga style's place in Meiji art history.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

In his later years, Kiyochika's focus shifted away from the landscape prints that had made his name. He continued to work as an illustrator and cartoonist, but the golden age of ukiyo-e was definitively over, eclipsed by photography, lithography, and other Western media. Traditional woodblock printing was increasingly seen as outdated. Like many artists of his generation, Kiyochika faced financial difficulties and was sometimes forced to sell personal belongings or earlier works to make ends meet.

Despite these challenges, he continued to create art until shortly before his death. Kobayashi Kiyochika passed away on November 28, 1915, at the age of 68. At the time of his death, his groundbreaking contributions may not have been fully appreciated, overshadowed by newer artistic trends. However, the 20th century saw a resurgence of interest in his work, particularly his kōsen-ga landscapes.

Today, Kobayashi Kiyochika is recognized as a major figure in Japanese art history. He is celebrated as the "last master of ukiyo-e," not just chronologically, but because he infused the tradition with a new vitality and relevance during a period of immense change. His willingness to experiment and synthesize Japanese and Western aesthetics makes him a crucial precursor to the shin-hanga movement, which saw artists like Kawase Hasui and Hiroshi Yoshida revive the landscape print tradition in the early 20th century, often employing the atmospheric effects Kiyochika had pioneered. While perhaps not as widely influential in the West as predecessors like Katsushika Hokusai or Utagawa Hiroshige, whose works profoundly impacted Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists like Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, and Van Gogh through the wave of Japonisme, Kiyochika's art holds a unique and indispensable place.

Conclusion: A Light in the Meiji Transition

Kobayashi Kiyochika's artistic journey mirrors the complex trajectory of Meiji Japan itself. Rooted in the traditions of Edo, he embraced the challenges and opportunities of a modernizing world. Through his innovative kōsen-ga, he captured the ephemeral beauty and underlying tensions of Tokyo's transformation, mastering the interplay of light and shadow to create works of enduring atmospheric power. His satirical eye documented the social shifts, while his war prints reflected the fervent nationalism of the era. As a teacher, he helped nurture the next generation of print artists. More than just the last great ukiyo-e artist, Kiyochika was a visionary chronicler of his time, leaving behind a body of work that continues to illuminate the dawn of modern Japan. His prints remain a poignant testament to a world in transition, seen through the eyes of an artist who skillfully navigated the currents between tradition and modernity.