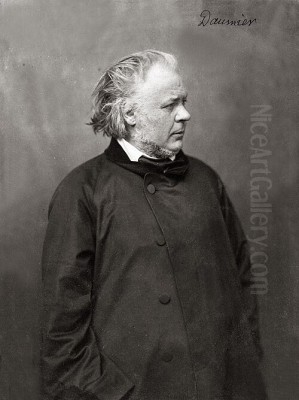

Honoré-Victorin Daumier (1808-1879) stands as one of the most formidable figures in 19th-century French art. A prolific master of caricature, a powerful painter, and an expressive sculptor, Daumier dedicated his life to observing and commenting on the social and political landscape of his turbulent times. His vast body of work, comprising thousands of lithographs, hundreds of paintings, and dozens of sculptures, offers an unparalleled visual record of Parisian life, marked by sharp wit, profound empathy, and an unwavering commitment to exposing hypocrisy and injustice. Though primarily known in his lifetime for his widely circulated satirical prints, Daumier's genius extended across mediums, earning him posthumous recognition as a key precursor to modern art movements.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born in Marseille in 1808, Daumier's origins were modest. His father, Jean-Baptiste Louis Daumier, was a glazier with literary ambitions, who moved the family to Paris in hopes of achieving recognition as a poet. This relocation plunged the young Honoré into the bustling heart of the French capital. Financial necessity forced him into the workforce at a young age; he served as an errand boy for a bailiff and later worked as a clerk in a bookstore. These early experiences provided him with intimate, firsthand exposure to the workings of the legal system and the diverse strata of Parisian society, particularly its less privileged members. This immersion would profoundly shape his artistic vision.

Despite the demands of work, Daumier's artistic inclinations were evident early on. He sought out instruction, initially studying drawing with Alexandre Lenoir, an archaeologist and artist who had himself been a student of the great Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David. This connection provided Daumier with a link, however indirect, to the academic tradition. However, Daumier was largely self-directed in his artistic development. He spent countless hours sketching at the Louvre, absorbing the lessons of the Old Masters, and crucially, he apprenticed himself to the lithographer Belliard, mastering the relatively new printmaking technique that would become his primary vehicle for expression and social commentary.

The Voice of Satire: Daumier the Lithographer

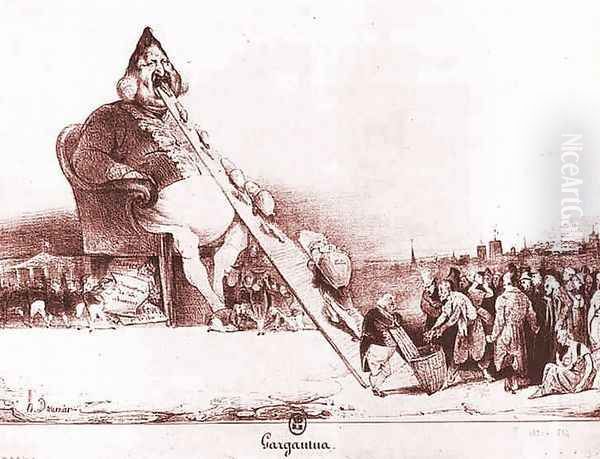

Daumier's career as a professional artist took flight in the politically charged atmosphere following the July Revolution of 1830, which installed Louis-Philippe as the "Citizen King." He began contributing sharp, insightful caricatures to newly established satirical journals, most notably La Caricature, founded by Charles Philipon, and later its successor, Le Charivari. These publications thrived on opposition to the regime, and Daumier quickly became their star contributor. His lithographs targeted the perceived greed, incompetence, and pomposity of the ruling bourgeoisie, politicians, lawyers, and judges.

His fearless satire often courted controversy and danger. In 1831, Daumier created one of his most infamous prints, Gargantua. This scathing caricature depicted King Louis-Philippe as the gluttonous giant from Rabelais's novel, consuming bags of coins extorted from the poor and excreting honours and positions for his favourites. The image was a direct and provocative attack on the monarch and the perceived corruption of his government. Its publication led swiftly to Daumier's arrest, prosecution, and a six-month prison sentence in Sainte-Pélagie in 1832.

Imprisonment did little to dampen Daumier's critical spirit. Upon his release, he resumed his work with renewed vigour, albeit sometimes employing slightly more veiled allegories. He produced masterpieces of graphic satire, including the chilling Rue Transnonain, le 15 Avril 1834, which depicted the brutal aftermath of a massacre where government troops killed innocent residents of a working-class apartment building following civil unrest. The print's stark realism and emotional power conveyed the horror of state violence with devastating effect.

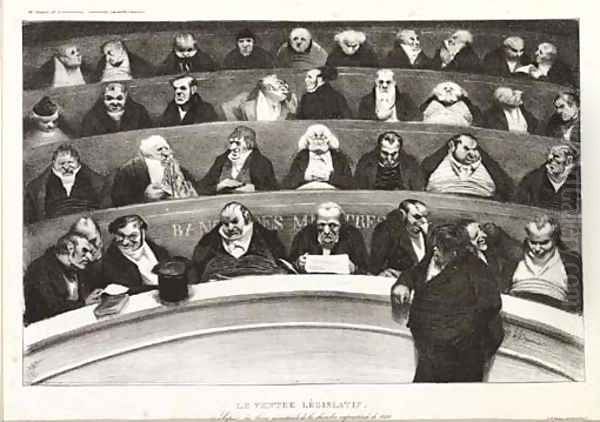

Another landmark work from this period is Le Ventre Législatif (The Legislative Belly, 1834), a group portrait of the members of the Chamber of Deputies. Rendered with unflattering accuracy, the politicians appear smug, self-absorbed, and largely inert, a collective indictment of a political system Daumier viewed as stagnant and self-serving. He also created popular series like the adventures of "Robert Macaire," a roguish charlatan figure used to satirize the dishonesty and speculation rampant in contemporary society. Through thousands of prints, Daumier became a visual chronicler of his era, his sharp lines and expressive exaggerations capturing the very essence – the "spiritual likeness" or 神肖 – of his subjects and their world.

A Different Vision: Daumier the Painter

While Daumier earned his living primarily through lithography, he harboured ambitions as a painter and sculptor throughout his career. His work in these mediums, often created privately and rarely exhibited during his lifetime, reveals a different facet of his artistic personality. While satire remained a component, his paintings often explored themes with greater nuance, depth, and a profound sense of humanity, particularly concerning the lives of the urban poor and working class.

His painting style was influenced by his deep understanding of form derived from drawing and sculpture, as well as his admiration for masters like Rembrandt, whose dramatic use of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) finds echoes in Daumier's own work. He was also connected to the burgeoning Realist movement, friendly with its leading figure, Gustave Courbet, and acquainted with Jean-François Millet, who shared his interest in depicting labourers. Though perhaps not formally part of the Barbizon School, his close friendship with Camille Corot and Charles-François Daubigny placed him within their circle. Some art historians also note affinities with the expressive intensity of Goya or the painterly touches reminiscent of Fragonard in certain works.

One of Daumier's most celebrated paintings is The Third-Class Carriage (c. 1862-1864). This work captures a group of working-class passengers huddled together in the cramped, dimly lit compartment of a railway carriage. Unlike his caricatures, there is no overt mockery here; instead, Daumier portrays his subjects with quiet dignity and empathy. The figures – a weary grandmother, a young mother nursing her child, a sleeping boy – convey the fatigue and resilience of ordinary people navigating the realities of modern industrial life. The composition is powerful, the forms simplified but solid, the light used effectively to highlight the central figures against the shadowed background.

Another recurring theme was that of The Washerwoman (La Blanchisseuse), which Daumier depicted in several paintings and drawings. These images show women burdened by heavy laundry, often accompanied by a child, trudging along the quays of the Seine. They are powerful representations of physical toil and maternal care, imbued with a sense of monumentality despite their humble subject matter. Daumier elevates the everyday labour of the poor to a subject worthy of serious artistic consideration.

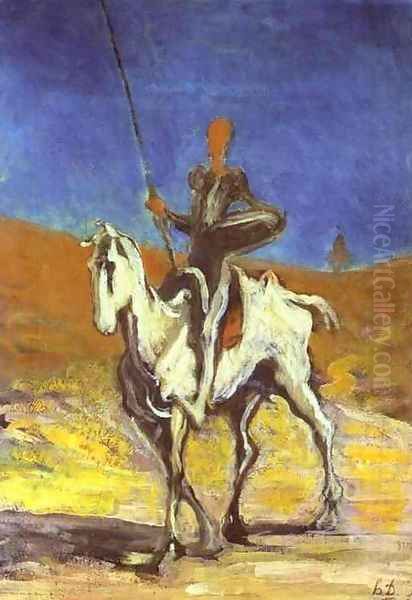

He also turned to literary and historical themes, notably producing a series of paintings and drawings depicting Don Quixote. These works capture the tragicomic essence of Cervantes's hero, the idealistic knight errant adrift in a mundane world. Daumier's interpretations often emphasize the loneliness and vulnerability of Quixote and Sancho Panza against vast, empty landscapes, exploring themes of illusion, reality, and the human condition with a blend of Realism and Romantic sensibility. Other subjects included scenes from the theatre, like Crispin and Scapin, and depictions of social unrest, such as The Uprising (L'Émeute).

Daumier's painting technique was often bold and direct, characterized by strong, expressive outlines, simplified forms, and a focus on capturing movement and essential character rather than minute detail. His canvases sometimes have an "unfinished" look that anticipates later modern developments, prioritizing emotional impact and structural solidity over polished surfaces.

Sculptural Expressions

Daumier's sculptural work, though less extensive than his graphic output, is equally significant and reveals his profound understanding of three-dimensional form. Starting in the early 1830s, he modeled a series of small, unbaked clay busts caricaturing prominent politicians and personalities of the July Monarchy. Known as The Celebrities of the Juste Milieu (roughly, "The Establishment Figures"), these sculptures served as models for his lithographs published in La Caricature. They are remarkable for their incisive characterization and expressive modeling, capturing the vanity, arrogance, or foolishness of their subjects with startling immediacy. Thirty-six of these fragile clay originals survive, later cast in bronze.

His most famous sculpture is likely Ratapoil (c. 1851), a full-figure statuette representing a swaggering, disreputable Bonapartist agent. With his lean physique, battered top hat, and menacing cudgel, Ratapoil became a symbol of the political thuggery and intimidation associated with Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte's rise to power. The sculpture embodies Daumier's critical stance towards the Second Empire, rendered with dynamic energy and psychological acuity. Like his paintings, Daumier's sculptures demonstrate his ability to convey complex ideas and social commentary through powerful, simplified forms.

Artistic Circle, Influences, and Impact

Throughout his long career, Daumier moved within the vibrant artistic and literary circles of Paris. His closest friend was perhaps the landscape painter Camille Corot, who provided crucial support, especially in Daumier's later years. He was also part of the circle associated with Charles-François Daubigny and frequented gatherings that included other artists. He maintained a friendly relationship with Gustave Courbet, the standard-bearer of Realism, and knew Jean-François Millet, whose depictions of peasant life resonated with Daumier's own focus on the working class. He worked alongside fellow lithographer Paul Gavarni for the same journals.

Daumier's work was admired by prominent figures. The great Romantic painter Eugène Delacroix respected his abilities and reportedly copied his works for study. The poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire was one of Daumier's earliest and most perceptive champions, recognizing the profound artistry beneath the surface of his caricatures. Baudelaire praised him lavishly, calling him "one of the most important men... not only in caricature, but also in modern art." Daumier's work also resonated with writers like Victor Hugo, who shared his republican ideals and concern for social justice.

While Daumier absorbed lessons from past masters like Rembrandt and Goya, and received foundational training linked to David via Lenoir, his own influence on subsequent generations was immense. His unflinching look at modern life, his candid compositions, and his expressive technique anticipated many aspects of Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. Artists like Edgar Degas and Édouard Manet were particularly drawn to his depictions of Parisian scenes and his bold drawing style; Degas himself was an avid collector of Daumier's work. Later artists, from Vincent van Gogh, who admired his draughtsmanship, to the Expressionists, found inspiration in his emotional intensity and social critique.

Enduring Themes and Social Commentary

Across all mediums, Daumier's work is unified by its persistent engagement with the social and political realities of his time. He was an eyewitness to decades of profound change and upheaval in France, living through the July Monarchy, the Revolution of 1848, the Second Republic, Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte's coup d'état and the Second Empire, the Franco-Prussian War, the Paris Commune, and the establishment of the Third Republic. His art serves as a running commentary on these events and the society they shaped.

His primary targets were hypocrisy, corruption, and abuse of power. He relentlessly satirized the legal system, portraying judges as indifferent or incompetent and lawyers as avaricious and manipulative. He mocked the pretensions of the bourgeoisie, their social climbing, and their cultural aspirations. He exposed the follies and failures of politicians across various regimes. Yet, his critique was balanced by a deep and abiding sympathy for the common people – the labourers, the laundresses, the street performers, the ordinary citizens caught in the machinery of the modern city and state. His work consistently champions the underdog and implicitly calls for greater justice and humanity.

Later Life, Recognition, and Legacy

Despite his productivity and the popularity of his prints, Daumier struggled financially throughout much of his life. Censorship laws under the Second Empire sometimes restricted his political satire, forcing him to focus more on general social commentary. In the 1870s, his eyesight began to fail, eventually leaving him nearly blind and unable to work. His financial situation became dire. In a gesture of profound friendship, Camille Corot gifted him a small house in Valmondois, a village outside Paris, allowing Daumier to live out his final years in modest security. He died there in 1879.

During his lifetime, Daumier was celebrated primarily as a caricaturist. His paintings and sculptures were rarely exhibited and remained largely unknown to the wider public. It was only towards the very end of his life and, more significantly, after his death that his full stature as an artist began to be recognized. An exhibition organized by his friends in 1878 at the Durand-Ruel galleries helped bring his paintings to greater attention. Critics and fellow artists increasingly acknowledged the power and originality of his work across all mediums.

Today, Honoré Daumier is universally regarded as a master of 19th-century art. He holds a unique position as both a brilliant satirist whose work reached a mass audience through print, and a profound painter and sculptor whose more personal creations explored the depths of the human condition. His incisive critique of society, his empathetic portrayal of ordinary life, and his bold, expressive style secured his place as a pivotal figure in the development of Realism and a significant precursor to Modernism. His works are housed in major museums around the world, including the Louvre, the Musée d'Orsay, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Museum of Modern Art, testament to his enduring power and relevance as an artist who captured the pulse of his time with unparalleled honesty and artistry.