Isaac Lazarus Israels stands as one of the most significant figures in Dutch art during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Aligned primarily with the Amsterdam Impressionism movement, he forged a distinct path, capturing the vibrant, fleeting moments of modern urban existence with an energy and immediacy that continues to resonate. Born into an artistic dynasty, he navigated the influences of his heritage and the burgeoning trends of European art to create a body of work celebrated for its dynamism, keen observation, and empathetic portrayal of everyday life, from the bustling streets of Amsterdam to the chic salons of Parisian fashion houses.

An Artistic Heritage and Early Promise

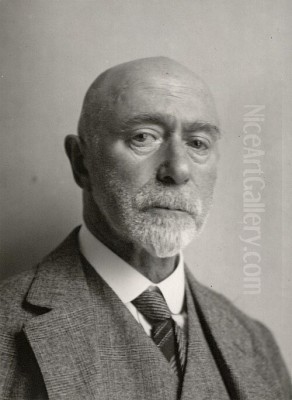

Isaac Israels was born in Amsterdam on February 3, 1865. Artistry was in his blood; his father was Jozef Israels, already a highly respected and internationally renowned painter associated with the Hague School. This connection provided young Isaac with an unparalleled immersion in the art world from his earliest years. Recognizing his son's burgeoning talent – Isaac reportedly began drawing and painting seriously by the age of six – Jozef provided encouragement and guidance. The family's move to The Hague in 1871 placed them at the heart of the Dutch art scene.

This environment proved fertile ground for Isaac's development. He received formal training at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague (Haagse Teekenacademie) starting around 1878. Here, he honed his technical skills but, perhaps more importantly, formed connections with other aspiring artists who would become significant figures in their own right. Among his fellow students were George Hendrik Breitner, Floris Verster, and Marius Bauer, individuals who, like Israels, would contribute significantly to the evolution of Dutch art.

Even in his youth, Israels demonstrated remarkable precocity. Before the age of twenty, he was already exhibiting work. An early painting, "Military Funeral" (1882), showcased his technical proficiency and ability to handle complex compositions, drawing favourable attention. Another work from this period, "Bugle Practice," was purchased by the artist and collector Hendrik Willem Mesdag even before it was completed, signalling the arrival of a major new talent. Despite this early success, particularly with military subjects, Israels felt his artistic education was incomplete, sensing a need to break away from the more traditional constraints of the Hague School style favoured by his father and many contemporaries like Anton Mauve or Willem Maris.

Amsterdam Impressionism and the Urban Scene

Seeking a different environment and artistic stimulus, Israels made a pivotal move to Amsterdam in 1886. There, he enrolled briefly at the Rijksakademie van beeldende kunsten (State Academy of Fine Arts) to further his studies, but his true education came from the city itself and his association with the literary and artistic movement known as the Tachtigers (The Eighties Movement). This group championed individualism, realism, and a focus on contemporary life, rejecting the perceived sentimentality of earlier styles.

In Amsterdam, Israels reconnected with George Hendrik Breitner. The two artists, though possessing distinct temperaments and eventually developing slightly different stylistic nuances, shared a profound fascination with the dynamism of the modern city. They became the leading figures of what is known as Amsterdam Impressionism. Unlike their French counterparts such as Claude Monet or Camille Pissarro, who often focused on the optical effects of light and landscape, Israels and Breitner were more concerned with capturing the raw energy, movement, and social fabric of urban life. Their work often possessed a grittier, more direct quality, reflecting the bustling, sometimes harsh realities of the rapidly industrializing city.

Israels set up a studio overlooking a lively canal, immersing himself in the daily theatre of Amsterdam. His canvases began to fill with scenes of crowded streets like the Kalverstraat or the Leidseplein, trams rattling by, people hurrying through rain-slicked avenues, servant girls chatting on bridges, and the vibrant chaos of marketplaces. He worked quickly, using bold, fluid brushstrokes and a relatively sober palette, often dominated by greys, browns, and blacks, punctuated by flashes of colour, to convey the immediacy of the moment. He sought not just the visual appearance but the feeling of the city – its pace, its atmosphere, its human stories unfolding in public spaces.

The World of Women and Work

A significant portion of Isaac Israels's oeuvre is dedicated to the depiction of women, particularly those occupying the diverse roles within the modern city. He moved beyond the idealized or purely domestic representations common in earlier art, focusing instead on women in the public sphere and the workplace. Shop girls ("winkeljuffers"), seamstresses, factory workers, telephone operators, and nursemaids became frequent subjects.

His interest often lay in capturing them during moments of unguarded activity – chatting during a break, concentrating on their tasks, or navigating the city streets. Works like "Two Shop Girls" or paintings depicting women sorting coffee beans reveal his keen eye for posture, gesture, and the subtle indicators of social class and occupation. He approached these subjects with empathy, portraying their lives without overt sentimentality but with a clear appreciation for their presence and vitality within the urban landscape.

This focus extended to women in leisure and entertainment. He painted scenes in cafes, dance halls ("Café Chantant"), and theatres, capturing performers and audience members alike. His fascination with movement and artificial light found ample expression in these settings. The quick, sketch-like quality of many of these works enhances the sense of a fleeting moment observed and recorded.

Parisian Chic: Fashion and Modernity

Around 1904, Israels began spending significant time in Paris, the undisputed capital of art and fashion. This period marked a notable shift in his subject matter and, to some extent, his palette, which brightened considerably under the influence of the Parisian atmosphere and French art. He established a studio there and became deeply involved in the world of haute couture, gaining access to prominent fashion houses like Paquin and Drecoll.

His Parisian works offer a fascinating glimpse into the exclusive world of high fashion at the height of the Belle Époque. He painted elegant clients trying on dresses, mannequins displaying the latest creations, seamstresses diligently working in ateliers, and the bustling activity behind the scenes. Works such as "Transport des modistes" (Transport of Milliners) or intimate views inside the salons of Maison Paquin capture the glamour, artistry, and labour involved in the fashion industry.

His connection with the fashion house Paquin, run by the innovative designer Jeanne Paquin, was particularly fruitful. He was allowed privileged access, enabling him to observe and sketch models, fittings, and the general milieu. These paintings are not just fashion plates; they are lively observations of social interaction, female elegance, and the modern spectacle of consumption and style. His brushwork remained energetic, perfectly suited to capturing the rustle of silk, the shimmer of fabric, and the animated gestures of models and clients. During his time in Paris, he also encountered leading figures of the avant-garde, including Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse, though his own style remained rooted in his Impressionistic approach rather than embracing Cubism or Fauvism. His work found more common ground with artists like Édouard Manet and Edgar Degas, who had earlier explored themes of modern Parisian life, cafes, and backstage scenes.

London Sojourn

Israels's restless spirit and quest for new subjects led him to London, where he lived and worked from 1913 to 1914, just before the outbreak of World War I. Although his time there was relatively brief, it was productive. He applied his characteristic style to capture the unique atmosphere of the British capital.

His London paintings often depict scenes different from his Amsterdam or Paris work. He painted young women practicing fencing, scenes of daily life in Hyde Park, and the ceremonial spectacle of horse guards. Theatre scenes also continued to attract him. While his London works retain his signature loose brushwork and focus on capturing movement and light, they sometimes reflect the different quality of light and the distinct social environment of London compared to the continental cities he knew so well. The impending war forced his return to the Netherlands.

Scheveningen Summers: Light, Air, and Leisure

Throughout his career, Israels frequently returned to the seaside resort of Scheveningen, near The Hague. These visits, often during the summer months, provided a counterpoint to his urban subjects. Here, his palette often became brighter and more luminous, reflecting the open skies and sun-drenched beaches.

His Scheveningen paintings are among his most beloved works. He captured the leisurely atmosphere of the beach, depicting elegantly dressed women strolling along the shore, children playing in the sand, and, most famously, the donkey rides that were a popular attraction. "Donkey riding on the beach at Scheveningen" is a recurring theme, rendered numerous times with variations in composition and light. These works perfectly encapsulate a sense of carefree summer days, the interaction of figures with the natural elements of sun, sea, and sand, and the simple pleasures of seaside life.

He demonstrated a remarkable ability to capture the specific light and atmosphere of the coast, differentiating the bright glare of midday sun from the softer tones of morning or evening. His figures, though often rendered quickly, possess individuality and charm. These beach scenes showcase a lighter, more relaxed aspect of Israels's art, complementing the dynamic energy of his cityscapes. His skill in capturing the subtle variations in the colour of wet and dry sand was particularly noted, earning him praise as a "poet of colour" even within the context of these seemingly simple leisure scenes.

Master of Portraiture

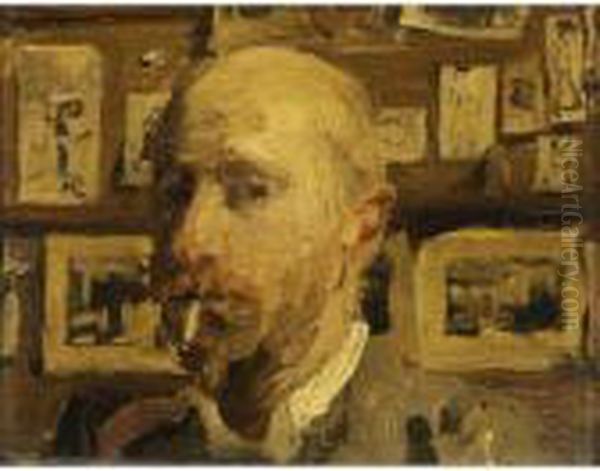

Alongside his scenes of daily life, Isaac Israels was a highly sought-after portrait painter. His approach to portraiture was consistent with his overall style: direct, insightful, and focused on capturing the sitter's personality and presence rather than achieving photographic likeness through meticulous detail. He worked quickly, often completing a portrait in a relatively short session, which contributed to the sense of immediacy and vitality in the finished work.

He painted numerous prominent figures of his time. Perhaps his most famous portrait subject was the dancer and courtesan Mata Hari, whom he depicted multiple times, capturing her exotic allure and enigmatic persona. He also painted portraits of the pioneering physician and feminist Aletta Jacobs, the actress Fie Carels, and fellow artist Thérèse Schwartze, a successful portraitist in her own right with whom he shared a studio building in Amsterdam for a time.

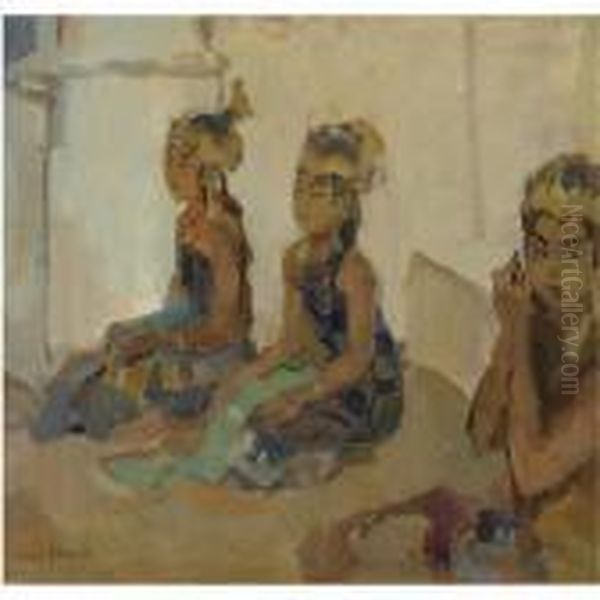

His portraits were not limited to the famous or wealthy. He also painted ordinary people, including some of the working-class women who featured in his genre scenes. A notable example reflecting a different aspect of his work is the portrait of Kees Pop, a soldier in the Royal Netherlands East Indies Army (KNIL). This work, painted during a period when Israels also documented military life in the Dutch East Indies (modern-day Indonesia) during travels there in the early 1920s, touches upon the complexities of Dutch colonial history. Regardless of the sitter's status, Israels aimed to convey their character through expressive brushwork and a focus on essential features and posture.

Style, Technique, and the Breitner Connection

Isaac Israels's style is characterized by its energy and spontaneity. His brushwork is typically loose, fluid, and visible, contributing to the sense of movement and the fleeting nature of the moments he depicted. While clearly aligned with Impressionism, particularly in his focus on light and contemporary life, his approach differed from the more analytical methods of some French Impressionists. He was less concerned with the scientific decomposition of colour and more interested in capturing the overall atmosphere and emotional tone of a scene. His use of colour could range from the relatively subdued palettes of his early Amsterdam street scenes to the brighter, more vibrant hues of his Parisian fashion paintings and Scheveningen beachscapes.

The relationship with George Hendrik Breitner is crucial to understanding Israels's place in Dutch art. They shared studios at times, explored similar subjects (particularly Amsterdam street life), and are often discussed together as the twin pillars of Amsterdam Impressionism. However, their styles were distinct. Breitner's work often feels heavier, more rugged, and perhaps more melancholic, while Israels's touch is generally lighter and more fluid. A famous anecdote recounts Breitner's feeling of being overshadowed by Israels's talent, suggesting a dynamic of both friendship and intense artistic rivalry. Breitner reportedly once remarked that true Dutch Impressionism was discovered in Amsterdam, but seeing Israels's work made him feel his own efforts were lacking in comparison. This highlights the significant impact Israels had even on his closest contemporaries. Comparisons can also be drawn with German Impressionists like Max Liebermann, who similarly depicted urban labour and leisure with vigorous brushwork.

Later Years, Recognition, and Legacy

After his travels, which also included trips to Spain and Italy, Israels eventually settled back in The Hague in 1923, moving into his late father's studio. He continued to paint actively, revisiting familiar themes but perhaps with a calmer, more reflective approach in his later years. His reputation was firmly established both in the Netherlands and internationally.

A significant honour came in 1928 when he won a gold medal at the Olympic Games in Amsterdam. At that time, art competitions were part of the Olympics, and Israels triumphed in the painting category with his work "Cavalier Rouge" (Red Rider), a dynamic depiction of a horseman likely inspired by his London observations of cavalry.

Isaac Israels died in The Hague on October 7, 1934, following a street accident a few days earlier. He was 69 years old. He left behind a vast and varied body of work that continues to be celebrated for its vitality and its insightful portrayal of an era of significant social and cultural change.

His legacy lies in his role as a key proponent of Dutch Impressionism, effectively bridging the gap between the Hague School and twentieth-century modernism. He captured the essence of modern life – its energy, its fashions, its work, its leisure – with a unique blend of keen observation and expressive technique. While some contemporary critics occasionally found his rapid execution superficial, his work has endured, appreciated for its immediacy, its atmospheric quality, and its empathetic connection to the human subjects he portrayed. Isaac Israels remains a pivotal figure, a chronicler of the pulse of Dutch life at the turn of the century, whose paintings offer a vibrant window onto a bygone world.