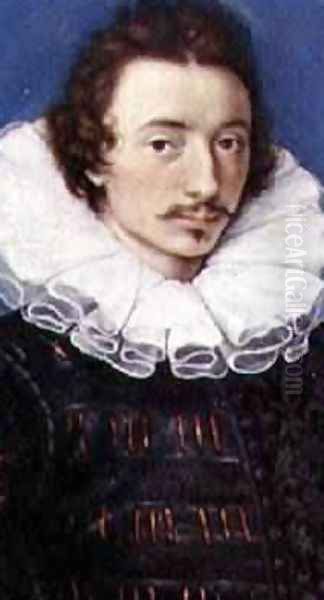

Isaac Oliver stands as one of the most accomplished and influential miniaturists of the late Elizabethan and early Jacobean periods in England. A French-born Huguenot refugee who found fame and fortune in his adopted land, Oliver transcended the prevailing artistic conventions of his time, infusing the intimate art of the portrait miniature with a new level of naturalism, psychological depth, and continental sophistication. His work not only captured the likenesses of royalty and aristocracy but also reflected the complex cultural and artistic currents of a transformative era in English history.

Early Life and Huguenot Origins

Isaac Oliver's story begins not in England, but in Rouen, France, where he was likely born around 1565, though some sources suggest a slightly earlier date, closer to 1560. His family were Huguenots, French Protestants who faced increasing persecution in their homeland, particularly in the years leading up to and following the St. Bartholomew's Day Massacre of 1572. Fleeing religious strife, his father, Pierre Ollivier, a goldsmith, brought the young Isaac and the rest of the family to London in 1568. This migration was part of a larger wave of skilled Protestant artisans and professionals from France and the Low Countries who sought refuge in England, enriching its cultural and economic life.

The Oliver family settled in London, a burgeoning metropolis that was becoming a significant centre for trade and the arts. Growing up in this environment, surrounded by fellow émigrés who often excelled in crafts such as jewelry, engraving, and painting, would have provided a stimulating backdrop for a young man with artistic inclinations. His father's profession as a goldsmith is also significant, as the meticulous skills required for goldsmithing – precision, attention to detail, and an understanding of precious materials – share common ground with the art of miniature painting, or "limning" as it was then known.

Artistic Apprenticeship and the Influence of Hilliard

The most crucial step in Isaac Oliver's artistic development was his apprenticeship under Nicholas Hilliard (c. 1547–1619), the preeminent English miniaturist of the Elizabethan era. Hilliard, who held the prestigious position of limner to Queen Elizabeth I, was the undisputed master of the art form in England. His style was characterized by its exquisite linearity, bright, even lighting, intricate detail, particularly in costume and jewelry, and a tendency towards emblematic and symbolic representation, often incorporating mottos or allegorical devices. Hilliard's miniatures, typically painted on vellum stuck to a playing card, were jewel-like objects, reflecting the Queen's own taste for elaborate and symbolic portraiture.

Oliver would have learned the foundational techniques of limning from Hilliard: the careful preparation of vellum, the grinding and mixing of pigments (often precious, like ultramarine from lapis lazuli and carmine from cochineal insects), the delicate application of watercolour and bodycolour with fine brushes, and the use of gold and silver for highlights and inscriptions. Hilliard himself documented some of these techniques in his treatise, A Treatise Concerning the Arte of Limning, written around 1600.

While Oliver absorbed Hilliard's technical mastery, he soon began to develop his own distinct artistic voice. By the late 1580s, Oliver's work started to show a departure from Hilliard's more insular, late-Gothic style, moving towards a greater naturalism and a more sophisticated understanding of light and shadow, or chiaroscuro. This divergence would eventually position him as Hilliard's chief rival, particularly appealing to a younger generation of patrons who were perhaps more attuned to continental artistic trends.

Emergence as an Independent Master

Around 1590, Isaac Oliver established himself as an independent artist. His burgeoning reputation was built on a style that, while retaining the exquisite detail of the miniature tradition, offered a more three-dimensional and psychologically nuanced portrayal of his sitters. He softened the hard outlines favored by Hilliard, using subtle gradations of tone to model faces and create a sense of volume. His figures often appear more relaxed and less formally posed than those in Hilliard's works, hinting at an inner life and a more personal connection between artist and sitter.

This period saw Oliver attract significant patronage from the English aristocracy. Among his early sitters were prominent figures at court, including Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I. Oliver's miniatures of Essex, often imbued with a fashionable melancholy, capture the charisma and ambition of this ill-fated nobleman. These works demonstrate Oliver's skill in conveying not just a physical likeness but also the sitter's personality and social standing.

His growing success allowed him to cultivate a sophisticated circle of acquaintances, including other artists and intellectuals. The émigré community in London remained a vital network, and Oliver's connections within this group, as well as his increasing access to the English court, were crucial for his career.

Travels to Venice and Continental Influences

A pivotal moment in Oliver's artistic development was his journey to Venice in 1596. Italy, and Venice in particular, was a powerhouse of Renaissance art, and exposure to its masterpieces had a profound impact on Oliver. In Venice, he would have encountered the rich colours and dynamic compositions of artists like Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), Tintoretto (Jacopo Robusti), and Paolo Veronese. He would also have seen the work of Northern Italian Mannerists such as Parmigianino, whose elegant and elongated figures may have resonated with Oliver's own refined aesthetic.

The Venetian school's emphasis on colour, light, and atmospheric effects seems to have reinforced Oliver's move away from Hilliard's linear style. His subsequent work often displays a richer palette, more dramatic use of chiaroscuro, and a greater sense of spatial depth. He also began to experiment with larger miniature formats and more complex compositions, including full-length figures and allegorical or mythological scenes, which were rare in English miniature painting before him. This exposure to Italian art, and possibly also to Flemish art through his travels or connections in London (artists like Frans Pourbus the Younger were active and influential), broadened his artistic horizons considerably.

The influence of continental art is also evident in his drawing style. A number of preparatory drawings by Oliver survive, revealing a confident and fluid hand, often using pen and wash to explore compositions and capture the play of light on form. These drawings, sometimes on a larger scale than his finished miniatures, show an artist thinking in terms of volume and plasticity, akin to his European contemporaries.

Mature Style and Royal Patronage

Upon his return from Venice, Oliver's style continued to mature, solidifying his reputation as a leading artist. With the accession of King James I in 1603, the artistic landscape in England began to shift. While Hilliard retained some royal favor, Oliver's more modern, continental style found particular appeal with the new Stuart court, especially with James's consort, Anne of Denmark, and their son, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales.

Anne of Denmark was a significant patron of the arts, with a taste for the sophisticated and the novel. She appointed Oliver as her official limner in 1604, a position that brought him prestige and a steady stream of commissions. He painted numerous portraits of the Queen, her children, and members of her circle. His miniatures of Prince Henry, a cultured and promising young heir, are particularly notable. These portraits often depict the Prince with an air of thoughtful intelligence and regal bearing, reflecting the hopes pinned on him. One famous example is the full-length miniature of Prince Henry (c. 1610-12), which shows him in a landscape setting, a format that Oliver helped popularize in English miniature art.

Oliver's work for the Jacobean court also included portraits of King James I himself, though perhaps fewer than of his family. His style, with its emphasis on naturalism and psychological insight, was well-suited to the more informal and intellectually inclined atmosphere of the Jacobean court, contrasting with the more iconic and symbolic imagery favored by Elizabeth I.

Other prominent patrons during this period included Lucy Russell, Countess of Bedford, a leading cultural figure and patron of poets like John Donne, and Thomas Howard, 2nd Earl of Arundel, one of England's first great art collectors. Oliver's association with such figures underscores his status within the cultural elite of Jacobean England.

Representative Works and Artistic Innovations

Isaac Oliver's oeuvre is rich and varied, showcasing his technical brilliance and artistic vision. Several key works highlight his innovations and stylistic characteristics.

One of his most iconic images is the Young Man Seated under a Tree (circa 1590-1595). This enigmatic full-length miniature depicts a melancholic young man, possibly a self-portrait or a portrait of a poet, in a pastoral landscape. The figure's introspective mood, the subtle modelling of his features, and the atmospheric rendering of the landscape all point to Oliver's departure from Hilliard's more decorative approach. It captures the fashionable Elizabethan and Jacobean trope of the melancholic lover or scholar.

His portraits of Queen Elizabeth I, though fewer than Hilliard's, are significant. An example from around 1595-1600 shows the aging queen with a degree of realism that is striking, yet still maintains her regal dignity. He does not shy away from depicting her age but does so with sensitivity, focusing on the power of her presence.

The so-called Rainbow Portrait of Elizabeth I (c. 1600-1602), a large-scale oil painting, has sometimes been associated with Oliver or his circle, possibly in collaboration with a painter like Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger. While his primary medium was miniature, the stylistic affinities, particularly in the modelling of the face, have led to such attributions, though they remain debated. This highlights the interconnectedness of artists working in different scales at the time.

A particularly innovative work is his miniature of Jesus Christ (c. 1600-1610). This piece demonstrates his mastery of a stippling or pointillist technique, using tiny dots of color to build up form and create soft transitions, reminiscent of the sfumato of Leonardo da Vinci or the delicate modelling of Correggio or Federico Barocci, whose work he may have encountered or seen through prints. This technique allowed for exceptional subtlety in rendering flesh tones and expressions.

Oliver also produced a number of "cabinet miniatures," which were larger than typical locket-sized portraits and intended for display in private cabinets or collections. These often featured full-length figures or small group scenes, such as The Three Brothers Browne and their Cousin, Sir Thomas Hanmer, with a Page (c. 1598), which showcases his ability to handle complex compositions and group dynamics within the miniature format.

His religious and mythological subjects, such as The Annunciation to the Shepherds or The Entombment, are rare but significant. These works, often based on prints after continental masters like Hendrick Goltzius or Abraham Bloemaert, demonstrate his ambition to elevate the status of miniature painting beyond mere portraiture, engaging with the grand themes of European art.

Relationship with Contemporaries

Isaac Oliver's career unfolded within a vibrant artistic community in London, which included both native-born English artists and a significant number of émigrés from the Low Countries and France.

His relationship with his former master, Nicholas Hilliard, evolved into one of respectful rivalry. While Hilliard remained influential, particularly with older patrons, Oliver's more naturalistic and psychologically penetrating style increasingly appealed to the Jacobean court and a younger generation. There is no evidence of animosity between them, but they represented distinct stylistic paths within the art of limning.

Oliver had close ties with the Gheeraerts family, another prominent artistic dynasty of Flemish origin. His third wife, Sara Gheeraerts, whom he married in 1602, was the daughter of Marcus Gheeraerts the Elder (c. 1520-c. 1590), a painter and printmaker, and the sister of Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (1561/2–1636), one of the leading large-scale portrait painters in Jacobean England. This marriage would have further integrated Oliver into the network of Netherlandish artists working in London and provided opportunities for artistic exchange. It is plausible that Oliver and Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger may have influenced each other, or even collaborated on occasion.

Other notable portrait painters active in England during Oliver's career included Robert Peake the Elder (c. 1551–1619), John de Critz (c. 1551/2–1642), who held the post of Serjeant Painter to the King, and later, William Larkin (early 1580s–1619), known for his strikingly patterned and detailed full-length portraits. While these artists primarily worked in oil on panel or canvas, their stylistic concerns and patronage circles often overlapped with Oliver's. The exchange of motifs and compositional ideas, often facilitated by prints, was common.

Oliver also had pupils, the most important being his own son, Peter Oliver (c. 1594–1647). Peter became a highly accomplished miniaturist in his own right, initially working in a style very close to his father's, and later developing his own distinct manner. He inherited his father's studio and continued to serve the Stuart court, notably producing miniature copies of Old Master paintings from the collection of King Charles I.

Personal Life and Family

Isaac Oliver's personal life is partially documented through records of his marriages and children. He married three times. His first wife was Elizabeth, with whom he had his son Peter. After Elizabeth's death, he married a woman named Luce in 1599. His third marriage, in 1602, was to Sara Gheeraerts, which, as mentioned, connected him to the influential Gheeraerts artistic family. Through his marriages, he had several children, though Peter is the most well-known due to his artistic career.

Oliver resided for much of his career in Blackfriars, London, an area popular with artists and craftsmen, partly due to its traditional liberties which offered some protection from City guild regulations. His will, dated 4 June 1617, provides insights into his possessions, his faith, and his concern for his family. He bequeathed his drawings and limning materials to his son Peter, ensuring the continuation of his artistic legacy. The will also expresses his Protestant faith, reflecting his Huguenot heritage.

Later Years and Death

Isaac Oliver continued to work actively until his death. He remained in demand as a portraitist, and his later works show a continued refinement of his style, often characterized by a subtle melancholy and a deep understanding of character. He died in London in October 1617 and was buried on October 2nd in St. Anne's, Blackfriars, the same church where his contemporary, the playwright Ben Jonson, also worshipped and where Anthony van Dyck would later be buried.

His death marked the end of an era for English miniature painting. He had taken the art form to new heights of naturalism and psychological expression, bridging the gap between the more symbolic art of the Elizabethan age and the burgeoning Baroque sensibilities of the 17th century.

Legacy and Art Historical Significance

Isaac Oliver's legacy is substantial. He is considered, alongside Hilliard, one of the two greatest masters of the English Renaissance miniature. However, while Hilliard perfected a distinctly English, late-Gothic style, Oliver opened English art to broader European currents, particularly those emanating from Italy and the Netherlands.

His key contributions include:

1. Enhanced Naturalism: He introduced a greater degree of realism and three-dimensionality to the miniature, using chiaroscuro and subtle modelling to create more lifelike and less stylized portraits.

2. Psychological Depth: His portraits often convey a sense of the sitter's inner life and personality, moving beyond mere likeness or social status.

3. Continental Sophistication: Through his travels and connections, he absorbed and adapted European artistic trends, enriching the insular tradition of English limning.

4. Expansion of Subject Matter: He experimented with mythological, allegorical, and religious subjects in miniature, as well as full-length portraits and group scenes, broadening the scope of the art form.

5. Influence on Subsequent Artists: His son, Peter Oliver, directly continued his tradition. More broadly, his emphasis on naturalism and sophisticated modelling paved the way for later miniaturists like John Hoskins (c. 1590–1665) and the supreme master of the English Baroque miniature, Samuel Cooper (1609–1672), who was Hoskins' nephew and pupil. Cooper, in particular, built upon the psychological intensity and painterly qualities that Oliver had introduced.

Isaac Oliver's miniatures are treasured today not only as exquisite works of art but also as invaluable historical documents, providing intimate glimpses into the faces and personalities of the men and women who shaped late Renaissance England. His ability to combine meticulous craftsmanship with profound artistic vision ensured his place as a pivotal figure in the history of English art, a master whose delicate creations continue to fascinate and impress. His journey from a refugee fleeing religious persecution to a celebrated court artist is a testament to his talent, resilience, and the rich cultural exchanges that characterized his era.