John White stands as a pivotal yet somewhat enigmatic figure in the annals of both English art and American exploration. Active during the latter half of the 16th century, primarily associated with the dates c. 1540–c. 1593, White was an Englishman of diverse talents: an accomplished artist, a keen-eyed explorer, a cartographer, and ultimately, a colonial governor. His legacy is inextricably linked to Sir Walter Raleigh's attempts to establish a permanent English settlement in North America, particularly the ill-fated Roanoke Colony. White's most enduring contribution lies in his remarkable series of watercolor paintings, which provide an unparalleled visual record of the Algonquian-speaking peoples of the North Carolina coast and the region's unique flora and fauna. These images represent some of the earliest and most informative European depictions of North American indigenous life and environment, securing White's place as a crucial chronicler of the nascent interactions between the Old World and the New.

Navigating Historical Uncertainty

Pinpointing the precise details of John White's life remains a challenge for historians. While the period of his significant activity is well-documented through his involvement in the Roanoke voyages (1584-1590), his exact birth and death dates are subject to some debate and conflicting records. Some sources suggest a birth year around 1540, while others propose closer to 1550. His death is generally placed around 1593, though concrete evidence is scarce. It is also important to distinguish him from other individuals named John White who lived in different periods, such as a John White Sr. (active much later) or a Canadian official. The John White relevant to art history and American colonization is the Elizabethan artist and governor associated with Roanoke. Despite these biographical ambiguities, the impact of his work is undeniable and provides the primary lens through which we understand his significance.

England in the Age of Exploration

John White emerged during a dynamic period in English history – the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. This era was characterized by burgeoning national confidence, maritime expansion, and a growing rivalry with Spain. Exploration and the prospect of New World colonies captured the imagination of adventurers, investors, and the Crown. Figures like Sir Francis Drake, Sir Humphrey Gilbert, and Sir Walter Raleigh were central to these ambitions. Artistically, England was absorbing Renaissance influences from the continent, though it still retained distinct characteristics. Portraiture was dominant, with artists like Nicholas Hilliard excelling in miniatures and George Gower serving as Serjeant Painter to the Queen. While these artists focused on the elite, White's work would take a radically different direction, focusing on ethnographic and natural historical observation in distant lands. The influence of earlier continental masters like Hans Holbein the Younger, who had worked in England, was still felt in the pursuit of realistic representation.

The Call of the New World: The Roanoke Voyages

John White's direct involvement with North America began through his association with Sir Walter Raleigh, a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I who was granted a charter to colonize the region. White likely participated in a reconnaissance voyage in 1584. However, his most significant artistic contributions stem from the 1585 expedition led by Sir Richard Grenville, which established the first settlement on Roanoke Island. During this period, White, alongside the scientist Thomas Harriot, was tasked with documenting the land, its resources, and its inhabitants. White served as the expedition's artist and surveyor, creating maps and, more importantly, the detailed watercolor drawings that would become his legacy. His role was crucial for conveying the nature of this new territory back to Raleigh and potential investors in England.

An Artist's Eye: Style and Technique

John White's artistic style was remarkable for its time and place. Working primarily in watercolor, he developed a technique that combined careful observation with skillful execution. His approach was noted for its naturalism, arguably surpassing much of the contemporary artistic output in England in its directness. He typically began with faint outlines in black lead (graphite), then applied watercolor washes directly onto the paper, often without extensive underdrawing. To enhance the vibrancy and detail, he employed bodycolor (opaque watercolor) and sometimes added highlights using gold, silver, and white pigments. This method allowed for both accuracy and a certain liveliness in his depictions. His focus on capturing the specific details of clothing, tools, plants, and animals set his work apart from the more formalized traditions prevalent in European court painting, as seen in the work of contemporaries like Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger or the Dutch painter Cornelis Ketel, who were active portraitists in England.

Picturing the Algonquian Peoples

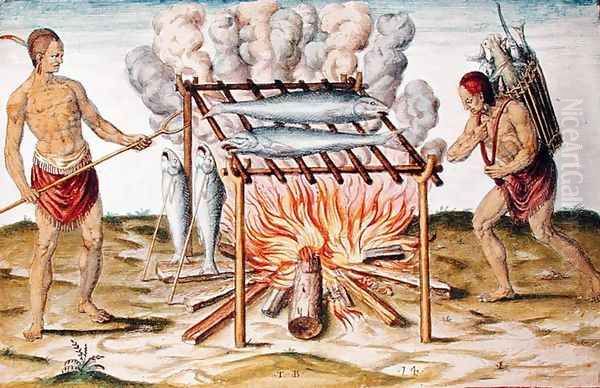

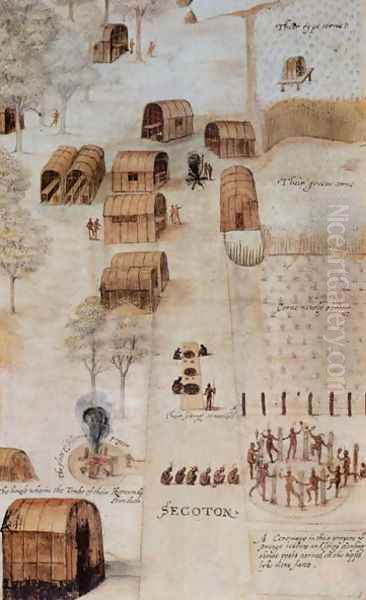

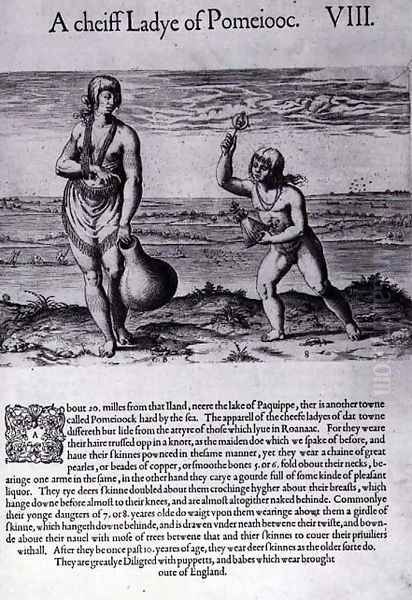

The most celebrated aspect of White's work is his depiction of the Algonquian peoples of the Outer Banks region, such as the Secotan and Pamlico tribes. His watercolors offer intimate glimpses into their daily lives, social structures, and cultural practices. He painted images of their villages, like Secotan, showing its layout and dwellings. He documented their attire, body paint, and hairstyles with meticulous detail. Scenes of everyday activities, such as The Manner of Their Fishing, Cooking in a Pot, and Cooking Fish, provide invaluable ethnographic information. He also recorded their ceremonies and rituals, including depictions of dancers (like A Dancer, which shows classical influences, perhaps recalling Greek sculpture) and religious figures. While inevitably viewed through a European lens, White's portrayals are generally considered more objective and less sensationalized than many other contemporary European representations of indigenous peoples. His work can be compared to that of the French Huguenot artist Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, who had documented the Timucua people in Florida two decades earlier, though White's style is often seen as more direct and less stylized.

Chronicling New World Nature

Beyond the human inhabitants, John White possessed a keen interest in the natural world of North America. His drawings include detailed studies of various plants and animals encountered along the Carolina coast. He depicted fish, birds (like pelicans and swans), turtles, crustaceans (like the horseshoe crab and hermit crab), and insects. His botanical illustrations captured species unfamiliar to Europeans, noting their appearance and sometimes their uses. These natural history drawings were significant not only for their artistic merit but also for their scientific value, contributing to the growing European understanding of American biodiversity. This careful observation of nature echoes, in spirit, the detailed studies produced by earlier Renaissance masters like Albrecht Dürer, although White's context and medium were entirely different. His work provided tangible evidence of the resources and novelties the New World offered.

Mapping the Unknown Coast

While primarily remembered for his watercolors, John White was also a cartographer. He produced maps of the Virginia and Carolina coastal regions based on the explorations undertaken during the expeditions. These maps, though perhaps less accurate by modern standards, were crucial navigational and informational tools for the English colonists and their sponsors back home. They represented some of the earliest English attempts to chart this part of the North American coastline systematically. His mapmaking activities demonstrate the close link between art, science, and exploration during this period, where visual representation was essential for understanding and claiming new territories. His skills likely complemented those of Thomas Harriot, the expedition's scientist and surveyor.

Governorship and the "Lost Colony"

White's involvement with Roanoke deepened significantly in 1587 when he sailed again, this time as the governor of a new group of colonists, including women and children, intended to establish a permanent settlement, "The Cittie of Raleigh," planned for the Chesapeake Bay area but ultimately landing back at Roanoke. This group included his own daughter, Eleanor White Dare, and his son-in-law, Ananias Dare. Shortly after their arrival, on August 18, 1587, Eleanor gave birth to Virginia Dare, the first English child born in the Americas. Facing dwindling supplies, the colonists persuaded Governor White to return to England to organize relief. He departed in late August 1587, expecting to return quickly.

However, White's return was disastrously delayed. England's impending conflict with Spain, culminating in the Spanish Armada of 1588, meant that all available ships were commandeered for national defense. White's frantic efforts to secure passage back to Roanoke were thwarted for nearly three years. When he finally managed to return with a relief expedition in August 1590, he found the settlement deserted. The only clues left behind were the word "CROATOAN" carved on a post of the fort palisade and "CRO" carved on a tree. Croatoan was the name of a nearby island (modern Hatteras Island) and the Native American group who lived there. Bad weather and reluctance from the ship's crew prevented White from sailing to Croatoan to investigate further. He was forced to return to England, never knowing the fate of his family and the other colonists. The disappearance of the Roanoke settlers remains one of American history's most enduring mysteries, known as the "Lost Colony."

Dissemination and Influence: The De Bry Engravings

While John White's original watercolors were seen by a limited audience in England, his images reached a much wider European public through the work of the Flemish engraver and publisher Theodor de Bry. Based in Frankfurt, de Bry included engravings based on White's drawings (alongside those of Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues) in the first volume of his grand illustrated collection of voyages, America, published in 1590. Thomas Harriot's A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia was published with these engravings. De Bry and his workshop adapted White's watercolors into copperplate engravings, sometimes altering details, adding Europeanized features, or composing scenes more dramatically to appeal to European tastes. Despite these modifications, the engravings were hugely influential, shaping European perceptions of North American peoples and landscapes for generations. They became the standard visual reference for the region, copied and re-copied in numerous publications across Europe.

Later Life and Enduring Legacy

After his heartbreaking return from Roanoke in 1590, John White seems to have faded into relative obscurity. Records suggest he may have retired to property in Ireland. The exact circumstances and date of his death remain uncertain, but it is often cited as occurring around 1593. Despite the personal tragedy and the colonial venture's failure, the body of work he created during his American voyages survived. His original watercolors eventually passed into the collection of the British Museum, where they remain treasured artifacts. These delicate works stand in contrast to the more robust oil portraits of the English elite created by contemporaries like William Scrots (painter to Edward VI) or the Flemish émigré Lucas de Heere, highlighting the unique nature of White's contribution.

John White's significance lies in his unique position as an artist-explorer who provided a firsthand visual account of a specific Native American culture and environment at the moment of early contact with Europeans. His watercolors are invaluable historical documents, offering insights into Algonquian society, material culture, and the natural world of coastal Carolina that written accounts alone cannot provide. They are also works of considerable artistic merit, demonstrating skill, sensitivity, and a remarkable degree of observational accuracy for their time. While modern scholarship acknowledges the inherent European perspective and potential biases within his work, his images are generally regarded as relatively faithful representations, especially when compared to later, more fanciful depictions.

White's Place in Art and History

John White occupies a distinct niche in art history. He was not a court painter or a producer of grand religious or mythological scenes. Instead, he was an expeditionary artist whose work served the practical needs of exploration and colonization while simultaneously achieving artistic excellence. His focus on ethnographic detail and natural history aligns him with a tradition of documentary illustration that gained increasing importance with European global expansion. His watercolors are considered among the most important visual sources for understanding Elizabethan England's engagement with the Americas and the indigenous cultures it encountered. They continue to be studied by historians, anthropologists, art historians, and the public, offering a compelling window onto a lost world and the complex beginnings of Anglo-American history. His legacy is preserved not only in the originals but also in the widespread influence of the de Bry engravings, which cemented his images in the European consciousness for centuries. John White remains a testament to the power of art to record, interpret, and shape our understanding of the past.