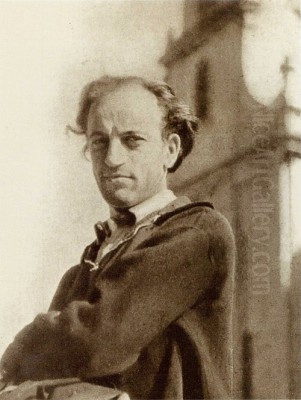

Lajos Vajda stands as one of the most significant and original figures of the Hungarian avant-garde in the interwar period. Despite a tragically short life, his prolific output and unique artistic vision left an indelible mark on Hungarian modern art. Vajda masterfully synthesized diverse influences, ranging from Eastern Orthodox icons and Hungarian folk art to Cubism, Surrealism, and Constructivism, creating a visual language that was both deeply personal and universally resonant. His work explored themes of spirituality, human suffering, and the looming catastrophe of war, often employing a distinctive technique of layering transparent motifs.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Lajos Vajda was born in Zalaegerszeg, Hungary, on August 6, 1908. His early years were marked by familial movement; in 1923, the Vajda family relocated from Serbia to Szentendre, a picturesque town on the Danube Bend. Szentendre, with its rich tapestry of Serbian Orthodox churches, Baroque architecture, and vibrant folk traditions, would later become a crucial source of inspiration for Vajda's art. This environment, steeped in diverse cultural and religious influences, undoubtedly planted early seeds in the young artist's mind.

Vajda's formal artistic education began in 1927 when he enrolled at the Hungarian Academy of Fine Arts in Budapest. He studied under István Csók, a prominent figure associated with Post-Impressionism and the Nagybánya artists' colony, though Csók's more traditional approach likely served more as a foundational base than a direct stylistic influence on Vajda's later radicalism. During his time at the Academy, which lasted until 1930, Vajda was already beginning to absorb the currents of modern European art, showing an early inclination towards abstraction and avant-garde principles. He formed a significant friendship with the philosopher and art theorist Lajos Szabó, a connection that would prove intellectually stimulating.

Even in these formative years, Vajda was drawn to the work of Hungarian cultural giants like composers Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály, who were similarly engaged in a project of modernizing Hungarian identity by drawing on authentic folk sources. This parallel interest in bridging tradition and modernity would become a hallmark of Vajda's artistic quest. His early works from this period, though still developing, began to hint at his later preoccupations with symbolic forms and a departure from purely representational art.

The Parisian Crucible: Exposure to the Avant-Garde

Between 1930 and 1934, Lajos Vajda immersed himself in the vibrant artistic milieu of Paris, a period that proved transformative for his development. Paris was then the undisputed capital of the art world, a melting pot of revolutionary ideas and movements. Vajda absorbed these influences voraciously, studying informally and engaging with the works of leading avant-garde figures. He encountered the radical formal innovations of Cubism, pioneered by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, which deconstructed objects into geometric forms and multiple perspectives.

He also came under the spell of Surrealism, a movement spearheaded by André Breton that sought to unlock the power of the unconscious mind through dream-like imagery and unexpected juxtapositions, as seen in the works of Salvador Dalí and Max Ernst. While in Paris, Vajda is said to have studied under Fernand Léger, whose own work evolved from a dynamic, machine-aesthetic Cubism towards a more figurative, monumental style. Léger's emphasis on strong outlines and bold, flat colors may have resonated with Vajda's developing graphic sensibilities.

Crucially, Vajda was exposed to the theories and techniques of Russian avant-garde cinema, particularly the principles of montage as developed by filmmakers like Sergei Eisenstein and Dziga Vertov. The concept of juxtaposing disparate images to create new meanings and a dynamic visual rhythm deeply influenced his approach to composition. He began to experiment with photomontage, a technique that allowed him to combine photographic elements with drawn or painted forms, creating complex, layered images. This period in Paris was also marked by his close association with fellow Hungarian artist Dezső Korniss, with whom he would later collaborate significantly. The intellectual ferment of Paris provided Vajda with the tools and conceptual framework to forge his unique artistic path.

Return to Hungary and the Szentendre Programme

Upon his return to Hungary in 1934, Lajos Vajda, together with his friend and fellow artist Dezső Korniss, embarked on an ambitious artistic endeavor known as the "Szentendre Programme." This project, developed between 1935 and 1936, aimed to create a distinctly Hungarian form of modern art by systematically collecting and synthesizing local motifs. Szentendre, with its rich multicultural heritage—Serbian Orthodox, Catholic, Jewish, and Hungarian folk traditions coexisting—provided a fertile ground for their research.

Vajda and Korniss meticulously documented the visual culture of Szentendre and its surrounding villages. They sketched architectural details from houses and churches, patterns from folk costumes and textiles, religious icons, gravestone carvings, and everyday objects. Their goal was not merely ethnographic documentation but the distillation of these elements into a modern artistic vocabulary. They sought to connect the "archaic" and "primitive" forms of folk art with the structural principles of Cubism and the symbolic resonance of Surrealism.

This program was a conscious effort to find an authentic, local wellspring for avant-garde expression, moving beyond direct imitation of Parisian trends. It was an attempt to create what they termed a "constructive surrealism," where the irrational and dreamlike qualities of Surrealism were grounded in a strong formal structure derived from folk and religious art. The Szentendre Programme was pivotal in Vajda's development, leading him to a deeper understanding of the symbolic power of local forms and providing him with a rich repertoire of motifs that would populate his mature works. Artists like Jenő Barcsay were also working in Szentendre, contributing to the town's reputation as an important artists' colony.

Mature Style: Transparency, Icons, and Premonitions

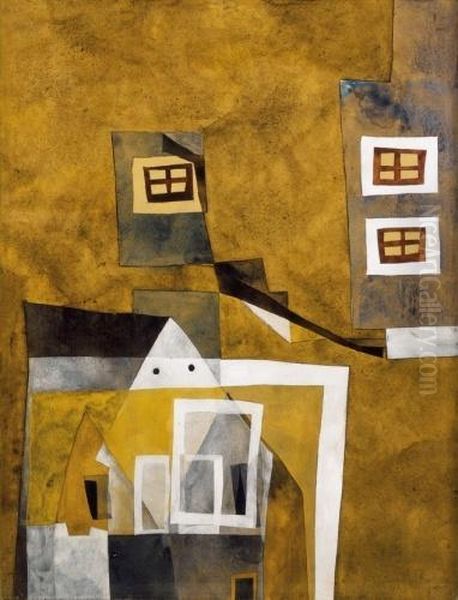

Lajos Vajda's mature style, which crystallized in the mid-to-late 1930s, is characterized by a unique synthesis of constructive principles and surreal, dream-like imagery. He developed a distinctive technique of "transparent" or "superimposed" drawing and painting, where multiple motifs—often derived from his Szentendre research—were layered one on top of another. These motifs, including fragments of icons, folk patterns, architectural elements, human figures, and natural forms, would interpenetrate and coexist on the picture plane, creating a sense of spatial ambiguity and multiple realities.

Icons, particularly Serbian Orthodox icons, held a profound fascination for Vajda. He was drawn not only to their spiritual content but also to their formal qualities: the flattened perspective, the strong outlines, the symbolic use of color, and the hierarchical arrangement of figures. In works like Self-Portrait with Icon and Hand (c. 1936) or Icon Self-Portrait, he often merged his own likeness with iconic imagery, suggesting a deep personal identification with these sacred forms and perhaps a search for spiritual solace in a troubled world. The influence of artists like Mikhail Vrubel or even the earlier icon painters themselves can be felt in this reverence for the iconic form.

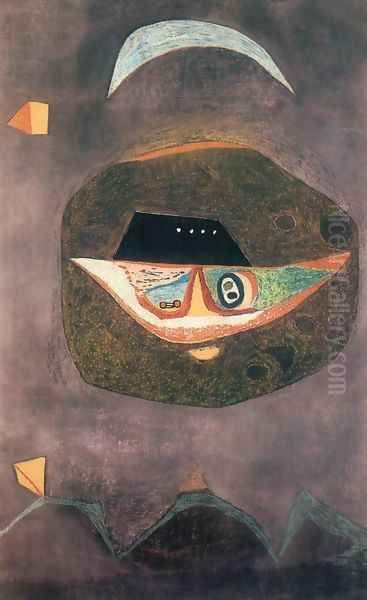

His works from this period, such as Floating Houses (1937) and Monster in Blue Space (1939), exhibit a growing sense of unease and foreboding. The familiar motifs of Szentendre houses might appear unmoored, floating in an undefined space, while strange, biomorphic or monstrous forms begin to emerge. These images can be interpreted as premonitions of the impending catastrophe of World War II and the rising tide of fascism in Europe. Vajda's art became a vessel for expressing a profound anxiety about the human condition and the fragility of existence. His unique visual language, blending the sacred and the mundane, the local and the universal, achieved a powerful symbolic resonance.

Key Themes and Artistic Language

The thematic concerns in Lajos Vajda's art are deeply intertwined with his personal experiences and the socio-political climate of his time. A recurring theme is human suffering, often conveyed through fragmented figures, distorted faces, and a general atmosphere of disquiet. This was not merely a personal angst but a reflection of the broader anxieties of an era marked by economic depression, political instability, and the looming threat of war. His Jewish heritage, in the context of rising anti-Semitism, undoubtedly added another layer to this sensitivity to persecution and vulnerability.

Spirituality is another central theme. Vajda's engagement with religious symbols—Orthodox, Catholic, and Jewish—was not necessarily an expression of conventional religious faith but rather an exploration of universal spiritual archetypes and a search for meaning in a world increasingly dominated by materialism and conflict. He saw in these ancient symbols a repository of collective memory and enduring human values. His use of iconographic elements, for instance, aimed to tap into their timeless power and integrate them into a contemporary artistic discourse.

Vajda's artistic language is characterized by its synthesis of abstraction and figuration. While his motifs are often recognizable, they are subjected to a process of simplification, fragmentation, and geometric stylization influenced by Cubism and Constructivism. The layering of these motifs, creating a sense of transparency and simultaneity, is a hallmark of his style. This technique, akin to a visual palimpsest, allows different temporal and spatial realities to coexist, suggesting the complexity and interconnectedness of experience. His palette often ranged from muted, earthy tones to more vibrant, expressive colors, depending on the emotional tenor of the work. The influence of artists like Paul Klee, with his own mystical and symbolic visual language, can be seen as a parallel exploration.

Representative Works: A Closer Look

Several works stand out as particularly representative of Lajos Vajda's artistic achievements and stylistic evolution.

Film (1928), an early work likely created during or shortly after his initial studies, already shows his interest in modern visual culture and dynamic composition. This piece, often a charcoal and watercolor, reflects the influence of cinematic montage, with fragmented images and a sense of movement, hinting at his later complex layering techniques. It demonstrates an early engagement with the dynamism of urban life and new media, a common theme among avant-garde artists of the 1920s like László Moholy-Nagy.

Houses at Szentendre with Crucifix (c. 1936-37) exemplifies the Szentendre Programme's fusion of local architecture and religious symbolism. The familiar gabled houses of the town are rendered with a constructive clarity, but they are overlaid or juxtaposed with a prominent crucifix, imbuing the everyday scene with a spiritual dimension. The work showcases his method of drawing motifs from his immediate environment and elevating them through symbolic association.

Floating Houses (1937) is a powerful example of his mature style, blending Surrealist dislocation with his characteristic transparency. Houses, detached from their foundations, drift in an ambiguous, dream-like space, conveying a sense of instability and vulnerability. The meticulous rendering of the individual elements contrasts with the irrationality of the overall composition, creating a poignant and unsettling image that speaks to the anxieties of the period.

Monster in Blue Space (or Mask with Moon) (1939-1940) is one of his late, haunting works. Here, a grotesque, mask-like face or monstrous form dominates a dark, ethereal space, often accompanied by a crescent moon. The imagery is stark and disturbing, reflecting the encroaching darkness of war and perhaps Vajda's personal struggles with illness and persecution. These late works often feature a more abstract and symbolic language, charged with emotional intensity. The raw power of these images can be compared to the wartime works of artists like Picasso (e.g., Guernica) or fellow Hungarian Imre Ámos, who also depicted suffering with visceral intensity.

Late Works, Persecution, and Tragic Death

The final years of Lajos Vajda's life were overshadowed by the escalating political crisis in Europe and his deteriorating health. As a Jew in Hungary, which was increasingly aligning itself with Nazi Germany, Vajda faced growing persecution. In the autumn of 1940, despite his already fragile health due to tuberculosis, he was conscripted into a forced labor battalion. This experience, common for Jewish men in Hungary during this period, was physically and emotionally devastating.

During his brief and harrowing periods of leave or hospitalization, Vajda continued to create art with a desperate urgency. His late works, primarily charcoal drawings, are stark, powerful, and deeply unsettling. They often feature grotesque, mask-like faces, skeletal figures, and abstract, tormented forms, reflecting his personal suffering and the collective trauma of war and persecution. These drawings, such as Charcoal Drawing with Yellowish-Brownish Monster Head (1940), are stripped of any decorative elements, conveying a raw, existential anguish. The expressive power of these late works is immense, bearing witness to the darkest chapter of European history.

Lajos Vajda's battle with tuberculosis, exacerbated by the harsh conditions of the labor service and the general deprivation of the times, ultimately proved fatal. He died in a sanatorium in Budakeszi on September 7, 1941, at the young age of 33. His premature death cut short a brilliant artistic career that was still evolving, leaving behind a legacy that would only be fully appreciated in the decades to come.

Artistic Affiliations and Collaborations

Throughout his career, Lajos Vajda was connected with various artistic currents and individuals, though he largely maintained a singular path. His most significant collaboration was with Dezső Korniss on the "Szentendre Programme." This partnership was foundational in shaping his approach to integrating folk motifs with modernism.

In his earlier years, Vajda was associated with the Munka-Circle (Work Circle), an avant-garde group active around 1928-1929, led by the influential artist and writer Lajos Kassák. Kassák was a towering figure in the Hungarian avant-garde, promoting Activism and Constructivism, and his journal Munka was a key platform for progressive artists. Vajda's involvement, though perhaps peripheral, indicates his early alignment with radical artistic tendencies.

While Vajda did not formally belong to many organized groups later in his career, his work resonated strongly with the aims of the European School (Európai Iskola), an important post-war Hungarian art group founded in 1945. Artists associated with the European School, such as Endre Bálint, Margit Anna (who was also deeply influenced by Vajda), Jenő Gadányi, and Ernő Kállai (the group's leading theorist), sought to reconnect Hungarian art with contemporary European modernism, particularly Surrealism and abstraction, while also valuing authentic local traditions. Vajda's oeuvre became a crucial point of reference and inspiration for this generation. Endre Bálint, in particular, played a role in promoting Vajda's legacy, though their personal relationship was complex, with Bálint sometimes seen as attempting to build his own artistic persona partly through his association with the deceased Vajda.

The Lajos Vajda Studio (Vajda Lajos Stúdió - VLS), founded in Szentendre in 1972, long after his death, was named in his honor. This group of younger, often neo-avant-garde artists, including figures like András Wahorn, saw Vajda as a spiritual predecessor, admiring his experimental spirit and his commitment to artistic integrity.

Legacy and Influence on Hungarian Art

Despite the brevity of his life and career, Lajos Vajda's impact on Hungarian art has been profound and enduring. He is widely regarded as one of the most original and important figures of the Hungarian avant-garde, a bridge between the early modernist pioneers like József Rippl-Rónai or Tivadar Csontváry Kosztka (in terms of seeking unique Hungarian expression) and the post-World War II generation.

His "Szentendre Programme," co-developed with Dezső Korniss, provided a model for how artists could engage with local traditions in a way that was neither sentimental nor academic, but rather a source for vital, contemporary artistic expression. This approach resonated deeply in a country often grappling with its cultural identity in relation to Western Europe.

Vajda's unique synthesis of Cubism, Surrealism, Constructivism, and folk/iconographic elements created a visual language that was distinctly his own. His technique of transparent layering and his exploration of spiritual and existential themes offered a rich alternative to both purely abstract art and social realism, the latter of which would dominate Hungarian art officially for several decades after his death.

His influence was particularly strong on the artists of the European School, who saw him as a key precursor. Figures like Endre Bálint, Margit Anna, and Imre Ámos shared his interest in Surrealist-inflected imagery, folk art, and themes of suffering and spirituality. The Lajos Vajda Studio (VLS) in Szentendre, founded in 1972, explicitly invoked his name and spirit, continuing his legacy of experimentation and critical engagement with tradition.

Today, Vajda's works are held in major Hungarian collections, including the Hungarian National Gallery in Budapest and the Ferenczy Museum Centre in Szentendre, which houses the Lajos Vajda Museum. His art continues to be studied and exhibited, recognized for its visionary quality, its technical innovation, and its poignant reflection of a turbulent era. He remains a testament to the power of art to confront difficult truths and to forge a unique vision against the odds. His work serves as an inspiration, demonstrating how an artist can draw from deep cultural roots while simultaneously engaging with the most advanced international currents of their time.