Ivan Aguéli, born John Gustaf Agelii, stands as a unique and compelling figure in the annals of art history. A Swedish painter, writer, and profound spiritual seeker, his life (1869-1917) was a vibrant tapestry woven with threads of European avant-garde art, deep engagement with Islamic mysticism, and a restless quest for universal truths. His journey took him from the quiet landscapes of Sweden to the bustling art circles of Paris, and ultimately to the spiritual heart of Egypt, leaving behind a legacy of art that is both aesthetically captivating and intellectually profound. Aguéli's work, characterized by its subtle coloration, spiritual luminosity, and synthesis of Western and Eastern sensibilities, continues to fascinate and inspire, offering a window into a soul that tirelessly sought to bridge worlds.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening in Sweden

John Gustaf Agelii was born on May 24, 1869, in Sala, a small town in Västmanland, Sweden. His father, Johan Gabriel Agelii, was a respected veterinarian. His mother, Anna Stina Nyberg, had familial connections to the lineage of Emanuel Swedenborg, the renowned 18th-century Swedish scientist, philosopher, theologian, and mystic. This ancestral link to Swedenborgian thought, with its emphasis on the spiritual world and correspondences between the material and the divine, may have subtly shaped the young Agelii's intellectual and spiritual inclinations from an early age.

His childhood and adolescence were marked by a burgeoning interest in both art and religion. These dual passions would become the guiding forces of his life. He received his early education in Gotland, an island known for its distinct medieval churches and serene landscapes, which likely provided early visual inspiration. He later continued his studies in Stockholm, the vibrant capital, where he would have been exposed to the prevailing artistic currents of the time, including the National Romanticism that was gaining traction in Scandinavia, as well as the lingering influences of academic art.

It was during these formative years that Aguéli began to seriously pursue painting. He initially studied under the Swedish artist Richard Bergh, a prominent figure in the "Opponenterna" (The Opponents) group, which rebelled against the conservative Royal Swedish Academy of Fine Arts. He also attended the Artists' Association School (Konstnärsförbundets skola) in Stockholm, a school founded by artists like Bergh, Karl Nordström, and Nils Kreuger, who advocated for a more modern and nationally rooted art. This environment fostered a spirit of independence and experimentation, which Aguéli would carry with him throughout his career. His early works from this period, though less known, began to show his sensitivity to landscape and a penchant for introspective moods.

Parisian Sojourns and Symbolist Encounters

The allure of Paris, then the undisputed capital of the art world, drew Aguéli, like many aspiring artists of his generation. He first traveled to Paris around 1890, a city teeming with new ideas and artistic movements. It was here that he adopted the name Ivan Aguéli, perhaps finding it more cosmopolitan or easier for French speakers. This period was crucial for his artistic development. He immersed himself in the avant-garde scene, seeking out instruction and inspiration.

A significant encounter during his early Parisian years was with Émile Bernard. Bernard, a complex figure associated with Cloisonnism and Synthetism, had been a close associate of Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh. Aguéli studied with Bernard in 1894, and Bernard's emphasis on simplified forms, bold outlines, and the subjective interpretation of reality resonated deeply with Aguéli's own evolving aesthetic. Through Bernard, Aguéli would have been further exposed to the ideas of Gauguin, who advocated for a move away from Impressionism towards a more symbolic and spiritually infused art. Some accounts even suggest Aguéli may have briefly been a student of Gauguin himself, though this is less definitively established than his tutelage under Bernard.

The Symbolist movement was at its zenith in Paris during the 1890s, and its influence on Aguéli was profound. Symbolism, reacting against Naturalism and Impressionism, sought to depict not objective reality but the subjective world of ideas, dreams, and emotions, often through allegorical or mythological imagery. Artists like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Puvis de Chavannes were leading figures, and their work, with its emphasis on mystery, spirituality, and the inner life, would have provided a rich intellectual and artistic environment for Aguéli. He was particularly drawn to the idea that art could be a vehicle for expressing profound spiritual truths, a concept that aligned with his early Swedenborgian influences and his burgeoning interest in esoteric thought.

During his time in Paris, Aguéli also associated with other Scandinavian artists, such as Carl Wilhelmson, and was part of a circle that included figures like Olof Sager-Nelson, another Swedish painter whose work shared certain Symbolist and introspective qualities. He also interacted with French artists like Maximilien Luce, a Neo-Impressionist with anarchist sympathies, which hints at Aguéli's developing political consciousness. His artistic output during this period began to reflect these influences, moving towards a more simplified, expressive style, with a focus on conveying mood and atmosphere rather than precise detail.

The Egyptian Years: Transformation and Artistic Flourishing

Aguéli's fascination with the East, particularly with Islamic culture and spirituality, grew steadily. This interest led him to make a life-altering decision: to travel to Egypt. He first arrived in Egypt in 1894 for a short period, but it was his extended stay from 1902 to 1912 that proved most transformative. He settled in Cairo, immersing himself in the local culture, learning Arabic, and studying Islamic philosophy and art.

This decade in Egypt was a period of intense artistic production and profound spiritual development. The light, colors, and architectural forms of Egypt captivated him. His paintings from this period are considered among his finest achievements. Works such as Egyptian Landscape, Mosque Tomb (The Dome of the Mamluk Tomb), and Egyptian Domed House (often titled Kupolbyggnad i Egypten) showcase his mature style. These paintings are characterized by their subtle, harmonious color palettes, often featuring soft ochres, blues, and grays, and a remarkable ability to capture the unique quality of Egyptian light – a "sacred light," as some critics have described it.

His Egyptian landscapes and cityscapes are not mere topographical records. They are imbued with a sense of stillness, timelessness, and spiritual presence. He often focused on simple architectural forms – domes, minarets, vernacular buildings – rendering them with a reductive clarity that borders on abstraction. This simplification was not for formalist ends alone; it was a way of distilling the essence of his subject, of conveying its spiritual resonance. His approach to composition was often intimate, focusing on small, carefully selected views rather than grand panoramas, lending his works a contemplative quality.

Beyond landscapes, he also painted portraits of Egyptians, capturing their dignity and inner life with sensitivity. These portraits, like his landscapes, often feature a muted palette and a focus on essential forms, sometimes with a subtle stylization, such as the slightly enlarged eyes in some figures, which can be seen as a way of emphasizing the spiritual or inner gaze. His deep respect for the culture and people he depicted is evident in these works, which stand in contrast to the often exoticizing or superficial portrayals of the "Orient" by some of his European contemporaries.

Spiritual Path: From Swedenborg to Sufism

Aguéli's journey into Islamic mysticism, or Sufism, was a natural progression of his lifelong spiritual quest. While his early exposure to Swedenborgianism had instilled in him a belief in a spiritual reality underlying the material world, his experiences in Paris and his studies of Eastern religions led him to explore other paths. In Egypt, he found a profound connection with Sufism, the esoteric dimension of Islam that emphasizes direct, experiential knowledge of God.

He formally converted to Islam, taking the name Abd al-Hādi (Servant of the Guide). This was not a rejection of his Western heritage but rather an expansion of his spiritual horizons, a search for universal truths that he believed transcended cultural and religious boundaries. He was initiated into the Shadhiliyya Sufi order, a prominent order known for its intellectual depth and its emphasis on spiritual purification and remembrance of God. His teacher was Sheikh ‘Abd al-Rahman Ilaysh al-Kabir, a respected scholar at Al-Azhar University.

Aguéli became a devoted practitioner and a keen student of Sufi metaphysics, particularly the teachings of Muhyiddin Ibn 'Arabi, the 13th-century Andalusian Sufi master whose concept of Wahdat al-Wujud (the Unity of Being) profoundly influenced him. Ibn 'Arabi's complex metaphysics, which posits that all existence is a manifestation of the One Divine Reality, resonated with Aguéli's artistic and spiritual search for unity and essential truth.

His engagement with Sufism was not merely personal; he saw himself as a bridge between East and West. He became one of the earliest Westerners to articulate Sufi teachings for a European audience. He collaborated with the Italian esotericist and convert to Islam, Gino (Abd al-Wahid) Pallazzi, and was instrumental in introducing the French philosopher René Guénon to Sufism. Guénon, who would later become a highly influential figure in the Traditionalist School of perennial philosophy (and also convert to Islam as Sheikh ‘Abd al-Wahid Yahya), acknowledged Aguéli's pivotal role in his own spiritual path. Aguéli founded a Sufi-oriented journal in Paris called Al-Maʿrifa (Gnosis) in 1904, though it was short-lived.

Philosophical and Literary Contributions

Beyond his painting, Ivan Aguéli was a thoughtful writer and philosopher. His writings, though not voluminous, offer valuable insights into his artistic theories, his spiritual understanding, and his critique of modern Western society. He contributed articles to various journals, often focusing on art criticism, Islamic philosophy, and the need for a spiritual renewal in the West.

His art criticism was informed by his spiritual perspective. He believed that true art must transcend mere representation and connect with a deeper, universal reality. He was critical of what he saw as the materialism and superficiality of much contemporary Western art and society. He advocated for an art that was imbued with spiritual significance, one that could serve as a means of contemplation and inner transformation. His ideas on art often echoed Symbolist principles but were further deepened by his understanding of Sufi aesthetics, which emphasize harmony, balance, and the reflection of divine beauty in the created world.

Aguéli's writings on Islam and Sufism were pioneering for their time. He sought to present these traditions to a Western audience in a way that was both authentic and accessible, challenging prevalent Orientalist stereotypes. He emphasized the intellectual and spiritual richness of Islamic civilization and the universal relevance of Sufi teachings. His efforts to promote a deeper understanding of Islam in the West were part of his broader vision of fostering a dialogue between cultures and spiritual traditions. He believed that the West had much to learn from the spiritual wisdom of the East, particularly in an age of increasing secularization and spiritual crisis.

His involvement with René Guénon and the nascent Traditionalist movement was significant. The Traditionalists, or Perennialists, argue for the existence of a primordial and universal tradition, a philosophia perennis, underlying all authentic religions and spiritual paths. Aguéli's own spiritual journey and his writings align with many of these ideas, particularly his emphasis on esoteric knowledge, traditional metaphysics, and the critique of modernity.

Artistic Style and Influences: A Synthesis

Ivan Aguéli's artistic style is a unique synthesis of various influences, filtered through his distinct personality and spiritual vision. It can be broadly characterized as a form of spiritualized Post-Impressionism with strong Symbolist underpinnings and an Orientalist subject matter approached with profound empathy.

Symbolism and Mysticism: The core of Aguéli's art lies in its Symbolist sensibility. Like other Symbolist painters such as Odilon Redon or the early Edvard Munch, he sought to evoke moods, ideas, and spiritual states rather than simply depict external reality. His use of light is particularly noteworthy; it often seems to emanate from within the painting, creating an atmosphere of serenity and contemplation. This "sacred light" is not merely descriptive but symbolic of spiritual illumination. His simplified forms and harmonious compositions contribute to this sense of otherworldly calm.

Post-Impressionist Techniques: Aguéli absorbed lessons from Post-Impressionism, particularly in his approach to color and form. While not adhering strictly to any single Post-Impressionist school, his work shares with artists like Paul Gauguin or Émile Bernard a move away from the fleeting perceptions of Impressionism towards more solid, structured compositions and a more subjective use of color. His palette, especially in his Egyptian works, is often characterized by subtle harmonies and a sophisticated use of muted tones, though he could also employ stronger contrasts for expressive effect. He was less interested in the scientific color theories of Neo-Impressionists like Georges Seurat or Paul Signac, and more focused on color's emotive and symbolic potential.

Orientalist Themes, Unconventional Approach: While his subject matter in Egypt places him within the broad category of Orientalist painters, Aguéli's approach differed significantly from many of his predecessors and contemporaries, such as Jean-Léon Gérôme or Ludwig Deutsch, whose work often emphasized the exotic, the sensual, or the picturesque in a way that catered to Western fantasies. Aguéli's depictions of Egypt are born from deep immersion and respect. He sought to capture the spiritual essence of the land and its people, avoiding clichés and focusing on the quiet dignity of everyday life and the timeless beauty of its sacred architecture.

Proto-Cubist Tendencies? Some art historians have noted certain formal qualities in Aguéli's work, particularly in his later portraits and architectural studies, that seem to anticipate aspects of early Cubism. His tendency to simplify forms into geometric planes, his interest in structure, and the way he sometimes subtly distorts or reconfigures elements for expressive or compositional purposes, can be seen as sharing a certain affinity with the explorations of form undertaken by artists like Paul Cézanne (a key precursor to Cubism) and, later, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque in their early Cubist phases. However, Aguéli's primary motivation was always spiritual and expressive rather than purely formal or analytical in the Cubist sense. The "exaggerated eyes" in some portraits, for instance, serve a symbolic, spiritual purpose rather than a purely formal deconstruction.

Influence of Swedenborg and Sufi Aesthetics: Underlying all these stylistic elements are the deeper influences of Emanuel Swedenborg's mystical cosmology and Sufi aesthetics. Swedenborg's doctrine of correspondences—the idea that every natural object corresponds to a spiritual reality—likely informed Aguéli's belief that art could reveal the spiritual in the material. Sufi aesthetics, with their emphasis on harmony, unity, and the reflection of divine attributes in art, further reinforced his quest for an art that was both beautiful and spiritually meaningful.

Key Works: A Glimpse into Aguéli's World

While Aguéli was not a prolific painter due to his peripatetic life and other intellectual pursuits, the works he did create are highly valued. Some of his most significant pieces include:

Egyptian Landscape (Egyptiskt landskap): These paintings, often small in scale, capture the unique atmosphere of the Egyptian countryside or city outskirts. They are characterized by their subtle light, harmonious colors, and a sense of profound stillness.

Mosque Tomb (Kupolbyggnad i Egypten / The Dome of the Mamluk Tomb): This is one of his most iconic images, depicting a Mamluk-era domed tomb. The simplified, almost abstract rendering of the dome against a luminous sky exemplifies his ability to convey spiritual monumentality through reductive means.

Egyptian Domed House (Egyptiskt kupolhus): Similar to the Mosque Tomb, these works focus on the simple, powerful geometry of vernacular Egyptian architecture, imbued with a sense of timelessness.

Portrait of a Woman (Egyptisk kvinna): Aguéli painted several portraits of Egyptian individuals. These works are notable for their sensitivity and dignity, capturing the sitter's inner presence. The forms are often simplified, and the gaze can be particularly expressive.

Gotland Landscape (Gotländskt landskap): From his earlier period or visits back to Sweden, these landscapes show his connection to his native land, often rendered with a similar sensitivity to light and atmosphere, though with a different palette reflecting the Nordic environment.

The Blind Man (Den blinde): A poignant work that reflects his interest in figures on the margins of society and perhaps carries symbolic weight regarding inner vision versus outer sight.

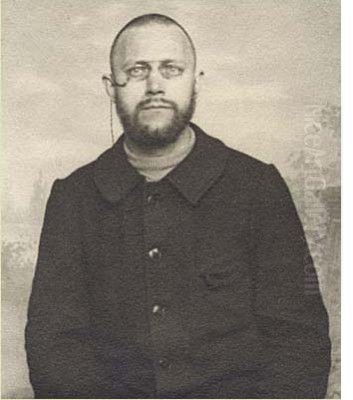

Self-Portraits: Aguéli painted a few self-portraits that offer a glimpse into his intense and introspective personality.

His works are primarily housed in Swedish collections, notably the Nationalmuseum in Stockholm, the Moderna Museet (Museum of Modern Art) in Stockholm, and the Aguéli Museum in Sala, his birthplace, which is dedicated to his life and art.

Contemporaries and Artistic Milieu

Ivan Aguéli's life and career intersected with a rich and diverse array of artists, thinkers, and movements. In Sweden, he was part of a generation that included established figures like Anders Zorn and Carl Larsson, whose styles were generally more naturalistic or National Romantic. However, Aguéli's path diverged towards a more modernist and international orientation, aligning him more with figures like Richard Bergh and the members of the Konstnärsförbundet, who sought new forms of expression. Olof Sager-Nelson, another Swedish Symbolist, shared some of Aguéli's introspective and spiritual concerns.

In Paris, the crucible of modern art, Aguéli moved within avant-garde circles. His association with Émile Bernard connected him to the legacy of Paul Gauguin and Vincent van Gogh, artists who had radically challenged artistic conventions. He would have been aware of the major Symbolist painters like Gustave Moreau, Odilon Redon, and Puvis de Chavannes, whose work explored themes of myth, dream, and spirituality. The intellectual climate of Paris also exposed him to anarchist thinkers and artists like Maximilien Luce.

His engagement with Eastern thought and his conversion to Islam set him apart from most of his European artistic contemporaries. While Orientalism was a popular theme, few Western artists immersed themselves as deeply in Islamic culture and spirituality as Aguéli did. His connection with René Guénon placed him at the forefront of the Traditionalist School, a philosophical movement that attracted intellectuals seeking alternatives to modern materialism. He also had a friendship with Marie Huot, a French writer and animal rights activist, with whom he corresponded, and Marie-Eugénie Wacha, an Egyptian woman who may have figured in his life in Egypt.

His artistic style, while unique, can be seen in dialogue with broader European trends. His simplification of form and expressive use of color resonate with the work of Post-Impressionists and early modernists. The spiritual intensity of his work might find parallels in the art of figures like the Norwegian Edvard Munch, though their modes of expression differed. Aguéli's contribution was his unique synthesis of these Western artistic currents with a profound understanding and personal experience of Eastern spirituality, particularly Sufism.

Political Engagements and Personal Turmoil

Aguéli's life was not solely dedicated to art and spirituality; he was also a man of strong political convictions, particularly drawn to anarchist ideals. During his time in Paris in the 1890s, he became involved in anarchist circles. Anarchism, with its emphasis on individual liberty, social justice, and critique of established power structures, appealed to his independent spirit and his concern for human dignity.

His political activities led to his arrest in Paris in 1894, implicated in anarchist plots, though the charges were likely tenuous. He spent several months in Mazas Prison. This experience, while undoubtedly difficult, may have further solidified his critique of societal injustices. His letters from prison reveal his longing for freedom and his intellectual resilience.

His life was often marked by financial precarity. He relied on intermittent support from patrons, including Prince Eugen of Sweden, himself an accomplished painter, and sales of his works, which were not always forthcoming. This lack of consistent financial stability added to the challenges of his peripatetic existence.

In 1900, while in Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), he was arrested by the British colonial authorities for allegedly shooting a sacred bull, though accounts of this incident vary and some suggest he was trying to protect the animal or was involved in an animal rights protest. This event underscores his often-impulsive nature and his willingness to confront authority or perceived injustice.

His later years in Egypt were also not without difficulty. In 1916, during World War I, with Egypt under British protectorate status, Aguéli, as a European with known unconventional views and associations, likely came under suspicion. He was accused of being an Ottoman spy—a charge that seems improbable given his character but plausible in the wartime atmosphere of paranoia. He was expelled from Egypt by the British colonial authorities.

Final Years and Tragic End

Forced to leave Egypt in 1916, Aguéli's health was reportedly declining, and he was suffering from increasing deafness. He made his way to Spain, a country with a rich Islamic heritage that perhaps appealed to him. He intended to travel on to Sweden. However, his journey was cut tragically short.

On October 1, 1917, at the age of 48, Ivan Aguéli was killed in a train accident near L'Hospitalet de Llobregat, just outside Barcelona. The exact circumstances of his death remain somewhat obscure. While officially an accident, some have speculated about other possibilities, given his past entanglements and the turbulent times. He was reportedly trying to board a moving train when he fell.

His death marked the premature end of a remarkable life dedicated to the pursuit of art, knowledge, and spiritual realization. His relatively small oeuvre, scattered and not widely known during his lifetime, would only gradually gain recognition.

Legacy and Enduring Influence

Despite the challenges and relative obscurity he faced during his lifetime, Ivan Aguéli's legacy has grown steadily, particularly in Sweden and among scholars of esoteric thought and East-West cultural exchange. He is now recognized as one of Sweden's most important early modernist painters and a key figure in Swedish Symbolism. His unique artistic vision, characterized by its spiritual depth, subtle beauty, and synthesis of diverse influences, has secured him a distinct place in art history.

The Aguéli Museum in Sala, his hometown, stands as a testament to his importance, preserving his works and promoting his legacy. His paintings are also held in major Swedish museums, ensuring their accessibility to new generations. Exhibitions of his work, though infrequent internationally, continue to draw attention to his unique contribution.

Beyond his artistic achievements, Aguéli's role as a pioneer in introducing Sufism to the West is of lasting significance. His influence on René Guénon and, through Guénon, on the broader Traditionalist School, has had a lasting impact on the study of comparative religion and esoteric philosophy. He is remembered as one of the first Europeans to embrace Islam not merely as an object of study but as a lived spiritual path, and to articulate its inner dimensions for a Western audience with authenticity and intellectual rigor.

His life and work continue to resonate with those who seek to bridge cultural divides, to find common ground between different spiritual traditions, and to explore the intersection of art, mysticism, and philosophy. Ivan Aguéli remains a compelling figure—an artist, a thinker, and a spiritual seeker whose journey offers profound insights into the human quest for beauty, truth, and unity.

Conclusion

Ivan Aguéli was a man of extraordinary complexity and depth. His life was a testament to an unyielding search for meaning, a journey that took him across geographical, cultural, and spiritual frontiers. As a painter, he created a body of work that is both visually enchanting and spiritually resonant, capturing the ethereal light of the North and the sacred landscapes of the East with a unique and sensitive vision. As a thinker and writer, he grappled with profound questions of art, philosophy, and religion, seeking to articulate a universal wisdom that could nourish a spiritually impoverished modern world. His embrace of Islam and Sufism, far from being an act of cultural exoticism, was a deeply personal and intellectually grounded commitment that enriched his art and his understanding of the divine. Though his life was cut short, Ivan Aguéli's legacy endures, inviting us to explore the luminous spaces he created and the bridges he sought to build between worlds.