Pierre Paul Girieud, a significant yet sometimes overlooked figure in early 20th-century European art, carved a unique path through the vibrant and rapidly evolving artistic landscapes of Paris and Munich. Born in Paris on June 17, 1876, and passing away in Le Pradet on September 26, 1948 (though some sources state his death in Paris), Girieud was a French painter whose career spanned several pivotal art movements. He was a self-taught artist who absorbed influences from Post-Impressionism, particularly Paul Gauguin, and became an active participant in Fauvism and a crucial link to German Expressionism. His journey reflects a deep engagement with the avant-garde currents of his time, marked by a distinctive use of color, form, and a persistent decorative sensibility.

Early Life and Artistic Awakening

Born into a Parisian family, Pierre Paul Girieud's early inclinations towards art were strong, leading him to defy his father's wishes for him to pursue a scientific education. This decision set him on a path of independent artistic exploration. Lacking formal academic training in the traditional sense, Girieud immersed himself in the study of masters, drawing inspiration from the romanticism of Eugène Delacroix and the rich, impastoed surfaces of Adolphe Monticelli. He was also significantly influenced by the Provençal painter Guillaume Guigou, whose work likely resonated with Girieud's later connection to the landscapes and light of Southern France.

His formative years were characterized by an intense period of self-discovery, absorbing the lessons of past masters while simultaneously seeking a contemporary voice. The artistic environment of Paris at the turn of the century was a crucible of innovation, and Girieud was well-placed to witness and partake in the dialogues that were reshaping European art. His early development shows a mind open to diverse influences, yet consistently striving for a personal mode of expression.

The Enduring Influence of Gauguin and the Nabis

A paramount influence on Girieud's artistic development was Paul Gauguin. Gauguin's departure from naturalistic representation, his use of bold, flat areas of color, strong outlines (Cloisonnism), and his pursuit of a more symbolic and spiritual dimension in art deeply impacted Girieud. This influence is evident in Girieud's adoption of non-traditional perspective, his preference for large, simplified planes of color, and his use of non-naturalistic hues to evoke emotion and enhance the decorative quality of his compositions.

Girieud's affinity for Gauguin's principles also aligned him with the Nabis, a group of young Post-Impressionist artists active in Paris from the late 1880s. Artists like Paul Sérusier, Pierre Bonnard, and Édouard Vuillard, who were themselves inspired by Gauguin, emphasized the decorative aspects of painting, the subjective experience of the artist, and the spiritual potential of art. Girieud's work, with its emphasis on flat patterns, simplified forms, and often a muted or symbolic palette, shared common ground with the Nabis' aesthetic, even if he wasn't a formal member. He embraced their tenet that a painting, before being a battle horse, a nude woman, or some anecdote, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.

Emergence with the Fauves

Pierre Paul Girieud emerged as a significant figure within the Fauvist movement, one of the first avant-garde movements of the 20th century. Fauvism, characterized by its explosive use of intense, non-descriptive color and vigorous brushwork, had its official debut at the 1905 Salon d'Automne in Paris. It was here that the critic Louis Vauxcelles, upon seeing a Renaissance-style sculpture surrounded by these wildly colored paintings, famously exclaimed, "Donatello au milieu des fauves!" ("Donatello among the wild beasts!"), thus giving the movement its name.

Girieud exhibited alongside key Fauvist figures such as Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Othon Friesz, Charles Camoin, and Georges Braque at this landmark 1905 Salon. His participation underscored his position within this radical group. While perhaps not as strident in his color choices as some of his Fauvist contemporaries, Girieud's work from this period clearly demonstrates a commitment to expressive color and simplified forms. He employed strong contrasts and bold outlines, often in black, to delineate his subjects, enhancing the decorative and emotional impact of his canvases. His Fauvist works often depicted landscapes, particularly those of Provence, imbued with a vibrant, subjective palette.

His involvement with Fauvism was not fleeting. He continued to exhibit with the group and was recognized as one of the "Fauves de Provence," alongside artists like Auguste Chabaud, highlighting his connection to the southern French landscape and its distinctive light, which had also inspired artists like Vincent van Gogh and Paul Cézanne.

Bridging Paris and Munich: Connections with German Expressionism

Beyond his role in French Fauvism, Girieud played a crucial part in fostering connections between the Parisian avant-garde and the burgeoning Expressionist movement in Germany. This was largely facilitated through his close friendship with the Russian émigré artist Wassily Kandinsky, a pioneer of abstract art, whom he met around 1904.

This friendship led to Girieud becoming the first French member of the Neue Künstlervereinigung München (NKVM), or New Artists' Association of Munich, co-founded by Kandinsky in 1909. The NKVM was a progressive group that sought to provide a platform for new artistic tendencies, and Girieud's involvement helped to create a dialogue between French and German artists. Other members of the NKVM included Alexej von Jawlensky, Gabriele Münter, Marianne Werefkin, and Franz Marc. Girieud exhibited with the NKVM, further solidifying his international presence.

When Kandinsky, Marc, and others broke away from the NKVM to form Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) group in 1911, Girieud also became associated with this seminal Expressionist collective. Der Blaue Reiter artists were interested in expressing spiritual truths through their art, exploring abstraction, and drawing inspiration from diverse sources including folk art and non-European cultures. Girieud's participation in their exhibitions, such as the first Der Blaue Reiter exhibition in Munich (1911-1912), demonstrates his alignment with their quest for an art that transcended mere surface representation to explore "inner life" and "spiritual elements." His correspondence with Marianne Werefkin further attests to his active engagement with this circle.

Artistic Style and Evolving Techniques

Girieud's artistic style, while rooted in Post-Impressionism and Fauvism, evolved throughout his career. A consistent thread was his commitment to the decorative. He often utilized simplified, almost monumental forms, and his compositions were carefully structured with an eye towards overall harmony and impact.

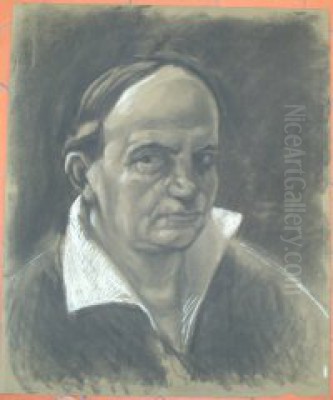

His use of color was a defining characteristic. In his Fauvist phase, colors were bold and often non-naturalistic, chosen for their expressive potential rather than descriptive accuracy. He employed strong contrasts to create visual dynamism. Even as his style shifted, a sophisticated understanding of color relationships remained central to his work. He was adept at using color to create mood and atmosphere, whether in his vibrant landscapes or his more introspective portraits and figure studies.

The influence of Gauguin's Synthetism, with its emphasis on flat planes of color and strong outlines, remained a recurring feature. Girieud often used dark contours to define shapes, a technique that lent a certain graphic strength to his paintings and enhanced their decorative quality. His perspective was often unconventional, flattening space to emphasize the two-dimensional nature of the canvas, a common trait among Post-Impressionist and Fauvist painters.

Later in his career, particularly after World War I, Girieud's style showed a tendency towards a form of classicism, a "return to order" that was seen in the work of many European artists during this period, including figures like Pablo Picasso and André Derain. This phase saw him engage more with traditional genres and a more tempered palette, though his inherent decorative sense persisted.

Representative Works and Thematic Concerns

Several works stand out in Pierre Paul Girieud's oeuvre, illustrating his stylistic development and thematic interests.

_Homage à Gauguin_ (1906): This painting, now in the collection of the Centre National des Arts Plastiques (CNAP) in Paris, is a clear testament to Girieud's admiration for the master of Pont-Aven. The work likely depicts figures in a landscape, rendered with the simplified forms, flat color planes, and symbolic undertones characteristic of Gauguin's influence. It serves as a pivotal piece acknowledging his artistic lineage.

_Portrait de jeune fille_ (Portrait of a Young Girl): This work is often cited as representative of his talent. While specific details of its execution and date might vary, portraits by Girieud typically show a sensitivity to the sitter combined with his characteristic stylistic traits – simplified forms, expressive use of color, and a focus on the decorative arrangement of the composition. Some critics, however, noted that such works, while showing talent, sometimes felt "too old" or not fully aligned with the most radical contemporary trends, perhaps reflecting his unique position between established influences and new movements.

Landscapes: Girieud produced numerous landscapes, often inspired by Provence. Works like _Paysage à la chapelle_ (Landscape with Chapel, 1927) and _Le Village_ (The Village, 1927) showcase his continued engagement with this genre. These later landscapes might exhibit a more subdued palette compared to his Fauvist period but retain a strong sense of composition and atmosphere. His interest in nature and rural scenes, including religious elements like chapels, was a recurring theme.

_Jeune femme nue au drapé_ (Young Nude Woman with Drapery, c. 1920): This work indicates his engagement with the classical theme of the nude, interpreted through his modernist lens. The simplification of form and the decorative treatment of drapery would be characteristic.

Throughout his career, Girieud explored various themes, including landscapes, portraits, nudes, and scenes with religious or symbolic overtones. His approach was consistently marked by a desire to imbue his subjects with an emotional and decorative resonance, rather than a purely naturalistic depiction.

Later Career and Decorative Arts

The period following World War I saw a shift in the artistic climate, with many avant-garde artists moving towards a more classical or restrained mode of expression. Girieud's work also reflected this trend. He increasingly turned his attention to decorative arts, a field that naturally aligned with his inherent stylistic preferences.

In 1924, he notably collaborated with architects on the decoration of transatlantic ocean liners, a prestigious commission that allowed him to apply his artistic vision on a large scale. This involvement in decorative projects extended to creating murals, designs for opera sets, and illustrations. This phase of his career underscores his versatility and his enduring interest in the integration of art into broader architectural and design contexts. His work in these areas would have emphasized harmonious compositions, stylized figures, and a sophisticated use of color suited to large-scale decorative schemes. This focus on decorative work continued until his death in 1948.

Relationships, Collaborations, and Artistic Circles

Pierre Paul Girieud was an artist who thrived on interaction and exchange within the artistic community. His friendship with Wassily Kandinsky was particularly significant, providing a vital link between the Parisian and Munich avant-gardes. Through Kandinsky, he connected with the NKVM and Der Blaue Reiter, participating in their exhibitions and intellectual dialogues.

His involvement in the Fauvist movement placed him in direct contact with its leading figures: Henri Matisse, André Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Othon Friesz, Charles Camoin, and Georges Braque. He exhibited alongside them and shared their revolutionary approach to color and form. He was also associated with the "Fauves de Provence," including Auguste Chabaud.

Girieud's network extended to other influential figures. His works were exhibited at the gallery of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, a key dealer who championed Cubist artists like Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, indicating Girieud's recognition within prominent avant-garde circles. He also painted a portrait of the celebrated writer Romain Rolland, suggesting connections beyond the immediate visual arts sphere.

He participated in significant group exhibitions, such as a 1910 show that featured works by Impressionist and Post-Impressionist masters like Claude Monet and Paul Cézanne, alongside contemporary artists. This demonstrates his engagement with the broader artistic currents and his place within the evolving narrative of modern art. His correspondence with artists like Marianne Werefkin further illustrates the breadth of his connections within the European art world.

Legacy and Historical Assessment

In art history, Pierre Paul Girieud is recognized as an important transitional figure. He was a dedicated participant in Fauvism, contributing to its development with his distinctive style. His deep admiration for Paul Gauguin and his alignment with Nabis principles shaped his aesthetic, emphasizing decorative qualities and subjective expression.

Perhaps one of his most significant contributions was his role as a conduit between French and German art movements. His membership in the NKVM and his association with Der Blaue Reiter facilitated crucial cross-cultural exchanges at a time when Munich was emerging as a major center for Expressionism. He helped to introduce French artistic ideas to Germany and, conversely, was exposed to the burgeoning spiritual and abstract concerns of the German Expressionists.

While Girieud may not have achieved the same level of international fame as some of his contemporaries like Matisse or Kandinsky, his work is valued for its unique synthesis of influences and its consistent artistic integrity. His paintings are characterized by a thoughtful use of color, strong compositional structure, and an enduring decorative sensibility. Critical reception during his lifetime was sometimes mixed, with some acknowledging his talent while others found his style occasionally retrospective. However, later reassessments, including retrospective exhibitions such as one at the Lehmbruck Museum in 1998, have helped to re-evaluate his contributions and affirm his place in the history of modern art.

His works are held in several prestigious museum collections, including the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, the Musée National d'Art Moderne at the Centre Pompidou in Paris, the Bavarian State Painting Collections in Munich, and the Centre National des Arts Plastiques (CNAP) in Paris. This presence in public collections ensures that his artistic legacy continues to be accessible for study and appreciation.

Conclusion

Pierre Paul Girieud's artistic journey was one of dedicated exploration and synthesis. From his self-taught beginnings and profound admiration for Paul Gauguin, he navigated the exhilarating currents of Fauvism and forged vital links with German Expressionism. His distinctive style, characterized by expressive color, simplified forms, and a strong decorative impulse, remained consistent even as he adapted to the changing artistic landscape of the early 20th century.

Though perhaps not always in the brightest spotlight, Girieud was an active and respected member of the avant-garde, a friend and collaborator to some of the era's most influential artists, and a painter whose work offers a unique perspective on the transition from Post-Impressionism to the radical innovations of modernism. His legacy lies in his distinctive body of work and in his role as a cultural bridge, enriching the dialogue between two of Europe's most vibrant artistic centers during a period of profound transformation.