Sir Joseph Noel Paton stands as one of the most significant artistic figures to emerge from Scotland during the vibrant and complex era of Queen Victoria. Born in 1821 and living until 1901, his life spanned a period of immense change, and his art reflects a unique blend of the imaginative, the spiritual, and the historical. Renowned primarily for his intricate and captivating paintings of fairies and mythological scenes, Paton also explored religious allegory, historical events, and portraiture, alongside pursuits in poetry, illustration, and sculpture. His dedication to his craft earned him widespread acclaim, culminating in his appointment as Queen's Limner for Scotland and the honour of a knighthood, cementing his legacy as a pivotal figure in 19th-century British art.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Joseph Noel Paton entered the world in Dunfermline, Fife, on December 13, 1821. His upbringing provided a fertile ground for his future artistic inclinations. His father, Joseph Neil Paton, was a successful damask manufacturer and designer, instilling in his son an appreciation for intricate patterns and craftsmanship. His mother, Catherine MacDiarmid, was an antiquarian with a deep interest in Scottish lore and history, nurturing his imagination with tales and legends from a young age. This combination of practical design sense and romantic storytelling would prove foundational to his artistic vision. The family environment was clearly supportive of the arts; his brother, Walter Hugh Paton, also became a noted landscape painter, often working alongside Joseph.

Paton received his initial education at Dunfermline Academy. His artistic talents were evident early on, leading him to further studies at the Dunfermline Art Academy. Practical experience followed when he spent three years working as the head of the design department at a cotton mill in Paisley, honing his skills in pattern and composition. However, his ambitions lay in fine art. In 1842, seeking more formal training, Paton travelled south to London to enrol in the prestigious Royal Academy Schools.

His time at the Royal Academy Schools, though relatively brief, was formative. He studied under the guidance of George Jones, a painter known for his military and historical scenes. London also exposed Paton to a wider artistic milieu, including the burgeoning movements and influential figures of the day. It was during this period that he began to forge connections and develop the distinct style that would characterise his career, blending meticulous technique with imaginative subject matter.

Rise to Prominence: The Fairy Paintings

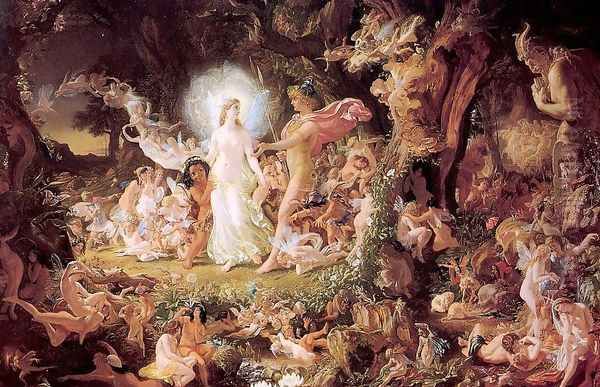

Paton burst onto the major art scene with a series of remarkable paintings centred on fairy lore, particularly drawing inspiration from Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream. These works captivated the Victorian imagination, which held a strong fascination for the supernatural, the miniature, and the unseen world. His two most celebrated works in this genre are The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania and The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania.

The Reconciliation of Oberon and Titania, completed in 1847, was exhibited at the Westminster Hall competition, a significant event designed to select artists for decorating the new Houses of Parliament. The painting was met with considerable praise for its intricate detail, imaginative composition, and delicate handling of the fairy figures. It depicted the moment of harmony restored between the fairy king and queen, surrounded by a host of fantastical creatures rendered with almost microscopic precision.

Two years later, in 1849, Paton completed its companion piece, The Quarrel of Oberon and Titania. This painting, even more complex and densely populated than its predecessor, depicted the moment of conflict from Shakespeare's play. Hundreds of fairy figures, sprites, goblins, and natural elements intertwine in a scene brimming with energy and minute detail. Exhibited again at Westminster Hall, it solidified Paton's reputation as a master of fantasy painting. The sheer density of detail invited viewers into an immersive, otherworldly realm. This work is now a highlight of the collection at the National Gallery of Scotland. These paintings showcased Paton's extraordinary ability for what was termed "mimetic realism" applied to the unreal, making the fantastical seem tangible.

Relationship with the Pre-Raphaelites

During his time in London, Paton encountered key figures of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB), notably John Everett Millais, who became a close friend. Millais, along with other founding members like Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt, admired Paton's meticulous technique and imaginative power. There was a clear stylistic affinity between Paton's work and the Pre-Raphaelite emphasis on truth to nature, bright colours, and complex compositions filled with symbolic detail.

Millais formally invited Paton to join the PRB. However, Paton ultimately declined the invitation. While sympathetic to their aims of revitalising British art and their commitment to detailed observation, his artistic path was diverging. He felt a strong pull back to his native Scotland and was perhaps less inclined towards the specific medievalist and modern-life subjects often favoured by the core PRB members. His interests remained rooted in mythology, folklore, history, and increasingly, religious allegory.

Despite not becoming an official member, Paton remained on friendly terms with Millais and others associated with the movement, such as Ford Madox Brown. His work continued to share certain characteristics with Pre-Raphaelitism – the jewel-like colours, the intricate detail, the narrative intensity – but he pursued these within his own thematic framework, establishing a distinct identity rather than adhering strictly to the Brotherhood's evolving doctrines. His decision reflected a desire for artistic independence and a commitment to his Scottish roots.

Broadening Horizons: Illustration, Poetry, and Sculpture

Paton's creative energies were not confined solely to painting. He was a man of diverse talents, actively engaging in illustration, poetry, and even sculpture throughout his career. His skill in detailed drawing and narrative composition made him a natural illustrator. He contributed illustrations to significant publications, including the Book of British Ballads (edited by S.C. Hall) and editions of Shakespeare's plays, most notably The Tempest. These illustrations often mirrored the intricate detail and imaginative flair of his paintings.

He was also a published poet, releasing volumes such as Poems by a Painter (1861) and Spindrift (1867). His poetry often explored similar themes to his visual art – mythology, spirituality, nature, and human emotion. This literary output underscores the deep connection between visual and verbal storytelling in his creative process, suggesting a mind constantly exploring different avenues for expressing complex ideas and narratives.

While less known than his paintings or illustrations, Paton also worked in sculpture. This aspect of his oeuvre is not as extensively documented or celebrated, but it demonstrates the breadth of his artistic interests and his willingness to experiment across different media. His engagement with multiple art forms highlights a holistic approach to creativity, common among some Victorian artists like William Morris or Rossetti, who also excelled in various disciplines.

Themes of History, Myth, and Legend

Beyond the realm of fairies, Paton delved deeply into historical subjects, mythology, and folklore, particularly drawing upon Scotland's rich cultural heritage. His mother's influence likely played a role here, fostering his interest in Celtic legends and national history. He shared this fascination with folklore with contemporaries like the Irish painter Daniel Maclise, who also explored mythological and historical themes with dramatic flair. Paton and Maclise are noted for their shared expertise in folklore, contributing significantly to the visual representation of these narratives in the 19th century.

His historical paintings often carried strong moral or patriotic messages. A notable example is In Memoriam (1858), created in response to the Indian Mutiny of 1857. The painting depicts a group of British women and children huddled together, anxiously awaiting their fate, a powerful and emotive image that resonated deeply with contemporary audiences grappling with the events of the Empire. This work showcased his ability to handle dramatic human emotion and historical context.

Paton's engagement with Scottish history and legend connected him to a longer tradition of Scottish artists interested in national identity, following in the footsteps of earlier figures like Sir David Wilkie, known for his genre scenes of Scottish life, and William Dyce, another versatile Scottish painter who worked across historical, religious, and decorative modes. Paton's contribution was unique in its particular blend of meticulous realism with romantic and often allegorical interpretations of these native themes.

The Shift Towards Religious Art

From around the 1860s onwards, while not entirely abandoning other subjects, Paton's focus increasingly shifted towards religious and allegorical themes. This later phase of his career produced works imbued with profound spiritual contemplation and moral seriousness. These paintings often took the form of large-scale allegories, aiming to convey complex Christian doctrines and ethical messages to a wide audience.

Works like The Man of Sorrows, Thy Will Be Done, and Beati Mundo Corde (Blessed are the Pure in Heart) exemplify this period. Valley in the Shadows of Death is another significant religious work from this time. These paintings often feature solitary figures or small groups in moments of spiritual trial, revelation, or devotion, rendered with clarity and emotional intensity.

The style of these later religious works is sometimes discussed in relation to the Nazarene movement, an earlier group of German Romantic painters based in Rome (including artists like Johann Friedrich Overbeck and Peter von Cornelius) who sought to revive Christian art through principles of simplicity, clarity, and moral purpose, inspired by early Renaissance masters. While Paton was not part of the Nazarene movement, his later works share a similar emphasis on clear narrative, didactic intent, and a departure from purely sensuous or decorative effects towards more austere spiritual expression. This shift reflected both his personal faith and a broader Victorian concern with art's moral and instructive potential.

Artistic Style and Technique

Sir Joseph Noel Paton's artistic style is characterized by several key features that remained relatively consistent throughout his career, despite shifts in subject matter. His most defining trait is arguably his meticulous attention to detail. Whether depicting the iridescent wings of a fairy, the texture of armour, the petals of a flower, or the expression on a human face, Paton rendered his subjects with extraordinary precision, often inviting close scrutiny from the viewer.

His use of colour was typically rich and vibrant, particularly in his earlier mythological and fairy paintings, contributing to their jewel-like quality. This aligns with the Pre-Raphaelite palette but was employed within his own compositional structures. His compositions are often complex and densely packed, especially in the large fairy scenes, creating a sense of teeming life and intricate narrative layers.

Paton masterfully blended realism with fantasy. His figures, even supernatural ones, possess a tangible quality, grounded in careful observation of anatomy and form. Yet, they inhabit worlds infused with imagination and symbolism. This ability to make the fantastical believable was central to his appeal. His work sits within the broader currents of Romanticism, with its emphasis on emotion, imagination, and the sublime, but it is filtered through a distinctly Victorian lens, incorporating moral seriousness and a fascination with detail.

Compared to other painters of fantasy, like the troubled Richard Dadd whose fairy paintings possess a feverish intensity, Paton's work is generally more ordered and allegorically clear. His style differs also from the softer, more ethereal fantasy of artists like Arthur Hughes, who was associated with the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism. Paton carved his own niche, influenced by various sources, including potentially the visionary intensity of William Blake (an influence acknowledged by his friend Millais), but ultimately creating a highly personal and recognizable style.

Recognition and Honours

Paton's talent and dedication did not go unrecognized during his lifetime. He achieved significant acclaim both in Scotland and beyond. He was elected an associate of the Royal Scottish Academy (RSA) in 1847, the same year his Reconciliation gained notice, and became a full academician in 1850. His works were regularly exhibited at the RSA and were often popular highlights.

A significant mark of royal favour came in 1865 when Queen Victoria appointed him Queen's Limner for Scotland. This prestigious role, essentially the monarch's official painter in Scotland, signified his pre-eminent status within the Scottish art establishment. Further honours followed swiftly. In 1867, he received a knighthood from Queen Victoria, becoming Sir Joseph Noel Paton. This recognition acknowledged his contributions not just as a painter but as a prominent cultural figure.

His paintings were acquired by major institutions and private collectors. The Royal Scottish Academy purchased some of his works for its collection, affirming his importance in the national artistic canon. His success was built on both critical acclaim for his technical skill and popular appeal stemming from his engaging subject matter and narrative power.

Personal Life and Legacy

In 1858, Paton married Margaret Gourlay Ferrier. The couple had a large family, raising eleven children together. His family life appears to have been a stable anchor amidst his busy artistic career. Two of his sons achieved distinction in their own fields: Diarmid Noel Paton became a Regius Professor of Physiology at the University of Glasgow, and Frederick Noel Paton served as Director-General of Commercial Intelligence for the government of India.

Paton maintained a lifelong connection to his roots and his family. He erected a memorial in Dumfries to his parents and siblings. His brother, Walter Hugh Paton, remained a close associate, sometimes travelling and sketching alongside him, particularly on trips like the one they took to the Isle of Arran, which inspired numerous works by both brothers.

Beyond his art, Paton was known as a collector, particularly of arms and armour, a passion possibly inherited from his father. He reportedly maintained a private museum in his home at Wooer's Alley, Dunfermline, showcasing a diverse collection that attracted visitors. Descriptions of his personality suggest he was optimistic and steadfast, a man of principle who held true to his word.

Sir Joseph Noel Paton died in Edinburgh on December 26, 1901, at the age of 80. He left behind a substantial body of work that continues to fascinate and engage audiences. His paintings are held in major public collections, including the National Gallery of Scotland in Edinburgh, the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow, and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, ensuring his contribution to British art remains accessible.

Conclusion

Sir Joseph Noel Paton occupies a unique and important place in the history of 19th-century British art. As Scotland's foremost painter of fantasy, he tapped into the Victorian fascination with the unseen world, creating intricate, immersive visions of fairy lore and mythology. Yet his artistic scope extended far beyond this, encompassing deeply felt religious allegories, poignant historical scenes, and insightful illustrations. Influenced by Romanticism and the technical innovations of the Pre-Raphaelites, he forged a distinctive style characterized by meticulous detail, rich colour, and compelling narrative. His roles as Queen's Limner and his knighthood attest to the high regard in which he was held. Paton's legacy endures through his captivating artworks, which continue to speak to the power of imagination, the complexities of faith, and the enduring allure of myth and legend.