Jules David (1808-1892), whose full name was often recorded as Jean-Baptiste David, stands as a significant, if sometimes overlooked, figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. He was a prolific painter and, more notably, a lithographer and illustrator, who carved a distinct niche for himself through his meticulous and stylish depictions of Parisian fashion. His work, disseminated widely through the burgeoning print media of the era, not only captured the sartorial trends of his time but also offered a window into the social aspirations and evolving aesthetics of Parisian society. While he may not have achieved the monumental fame of some of his contemporaries in the grander genres of painting, his contribution to the visual culture of fashion and the art of illustration remains undeniable and worthy of detailed exploration.

This article aims to delve into the life and work of Jules David, tracing his artistic journey, examining his signature style, and highlighting his most important contributions. We will explore the context in which he worked, the publications that carried his illustrations to a wide audience, and the ways in which his art reflected and shaped perceptions of elegance and modernity. Furthermore, we will situate him within the broader artistic milieu of his time, acknowledging his connections, however indirect, to other artists and the prevailing artistic currents that may have informed his practice.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Jules David was born in Paris on March 29, 1808, a period of significant social and political transition in France. He passed away in the same city on October 29, 1892, his life spanning a dynamic century of artistic innovation and societal change. Detailed information regarding his formal education in the arts is somewhat scarce in readily available records. However, it is known that he was a student of Pierre-Dominique Le Camus (sometimes cited as Pierre Duval Le Camus or similar variations). Le Camus himself was a painter of genre scenes and portraits and, significantly, had been a pupil of the formidable Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), the leading figure of French Neoclassicism.

This pedagogical lineage, though indirect, connects Jules David to one of the most influential artistic traditions in France. While Jules David's primary output would diverge significantly from the historical and mythological epics of Jacques-Louis David, the rigorous training and emphasis on draughtsmanship inherent in the Neoclassical school likely provided a solid foundation for his later career in illustration, where precision and clarity of line were paramount. The discipline learned under Le Camus would have been invaluable for the detailed work required in fashion plates and other illustrative commissions.

Unlike Jacques-Louis David, whose career was deeply intertwined with the French Revolution and the Napoleonic era, Jules David's professional life unfolded in the subsequent decades, marked by the July Monarchy, the Second Republic, the Second Empire, and the early years of the Third Republic. This was an era that saw the rise of the bourgeoisie, an increased emphasis on consumer culture, and the proliferation of illustrated journals and magazines, all of which created a fertile ground for an artist with Jules David's talents.

The Golden Age of Fashion Illustration

The 19th century witnessed an explosion in print culture, driven by advancements in printing technology, particularly lithography, and a growing literate public eager for information and entertainment. Fashion magazines became increasingly popular, catering to a burgeoning middle and upper class keen to keep abreast of the latest styles emanating from Paris, the undisputed fashion capital of the world. These publications relied heavily on skilled illustrators to translate the three-dimensional reality of garments into appealing two-dimensional images.

Jules David emerged as one of the preeminent artists in this specialized field. His illustrations were not mere functional diagrams of clothing; they were carefully composed scenes that often included contextual details, suggesting narratives and lifestyles associated with the depicted fashions. He possessed a keen eye for the nuances of fabric, cut, and embellishment, rendering textures and silhouettes with remarkable finesse. His figures, typically elegant and poised, embodied the fashionable ideal of the period.

His work appeared in some of the most influential fashion journals of the time, including the Journal des Demoiselles (Girls' Journal), Journal des Jeunes Personnes (Young People's Journal), and notably, Le Moniteur de la Mode (The Fashion Observer), for which he was a principal illustrator. His contributions to these publications were substantial; for instance, it is estimated that he produced around 2,600 fashion illustrations for the Journal des Demoiselles and Journal des Jeunes Personnes between approximately 1839 and 1842, and around 500 for Le Moniteur de la Mode.

Signature Style and Thematic Concerns

Jules David's style in fashion illustration was characterized by its elegance, clarity, and attention to detail. He typically depicted women, and occasionally men and children, in contemporary attire, often set against refined domestic interiors or picturesque outdoor settings. His figures were graceful, exuding an air of sophistication and propriety that appealed to the sensibilities of his target audience. He was adept at capturing the subtle shifts in fashion, from the voluminous skirts of the mid-century to the more streamlined silhouettes that emerged later.

His illustrations meticulously documented the evolution of Parisian style over several decades. For example, his work from the 1870s might showcase the elaborate confections of the "delicate Dresden style," while his later plates from the early 1890s could feature the "seven-inch foot, ten-inch waist" ideal that characterized certain fin-de-siècle fashions. These visual records are invaluable to fashion historians today, providing a rich archive of 19th-century dress.

Beyond simply recording garments, David's illustrations often hinted at the social roles and activities of the wearers. Scenes of women in walking dresses, visiting costumes, elegant ball gowns, or practical attire for leisure activities helped to construct an image of the ideal bourgeois lifestyle. The settings, whether opulent drawing-rooms, manicured gardens, or fashionable promenades, further reinforced these aspirational narratives. The inclusion of accessories, hairstyles, and even the posture of the figures contributed to the overall effect.

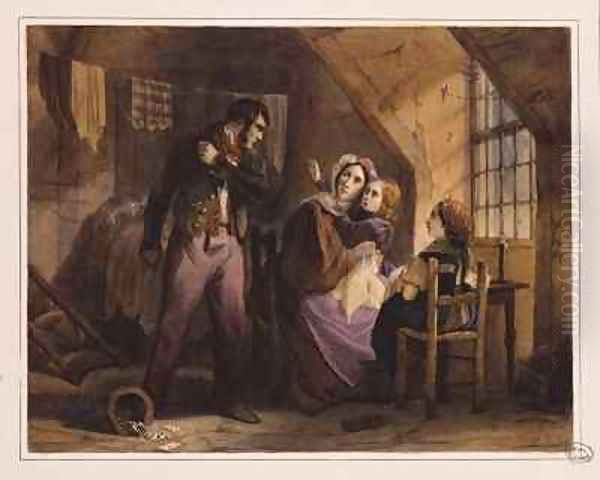

Some sources also indicate that Jules David engaged with other forms of illustration, including satirical works and illustrations for literary texts. He is credited with creating a series of twelve lithographs titled Vice and Virtue, which depicted stages of good and evil in life. Furthermore, illustrations for works such as Eugène Sue's The Wandering Jew and The Mysteries of Paris, as well as for a History of Napoleon and a work titled Morality in Action, are attributed to him. If these attributions are accurate for Jules David the fashion illustrator, they suggest a broader artistic range, encompassing social commentary and narrative art alongside his fashion work. His style in these areas was described as lively and humorous, sometimes critiquing political oppression and religious hypocrisy, aligning him with a tradition of French graphic satire famously exemplified by artists like Honoré Daumier.

Additionally, there are mentions of Jules David producing Gothic-style landscapes and interior decoration paintings, which would further broaden the scope of his artistic endeavors beyond the realm of fashion and popular illustration. A sketchbook by David, exhibited in 1987, offered further insight into his working methods and artistic vision.

Key Publications and Representative Works

The backbone of Jules David's fame and influence lay in his extensive contributions to fashion periodicals. His long association with Le Moniteur de la Mode was particularly significant. This journal, founded in the 1840s, was a leading voice in the dissemination of Parisian fashion trends, and David's plates were central to its appeal. These hand-colored lithographs or engravings were prized for their beauty and accuracy, serving as practical guides for dressmakers and fashionable women alike.

His work also reached an international audience. In the 1860s, he began creating hand-colored fashion illustrations for The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, a popular British publication. This demonstrates the transnational appeal of Parisian fashion and the role of illustrators like David in its global dissemination. His plates were often copied or adapted for use in magazines in Germany, Spain, the United States, and other countries, making his style recognizable far beyond the borders of France.

Among his specific named series, Vice and Virtue stands out as a departure from pure fashion, indicating an interest in moralistic or allegorical themes. However, it is his vast corpus of fashion plates that constitutes his most enduring legacy. These individual plates, often untitled beyond a generic description of the attire or the month of publication, collectively form a remarkable visual chronicle. Each plate, whether depicting a "Robe de Promenade," an "Ensemble de Soirée," or a "Costume d'Enfant," was a miniature work of art, carefully designed to be both informative and aesthetically pleasing.

The sheer volume of his output is staggering. The thousands of illustrations he produced over his long career attest to his diligence, skill, and the sustained demand for his work. These plates were typically produced using lithography or steel engraving, and then often meticulously hand-colored, usually by teams of women known as "coloristes," to bring the designs to life with vibrant hues.

The Artistic Milieu and Contemporaries

Jules David operated within a vibrant artistic ecosystem in 19th-century Paris. While his primary focus was illustration, the broader art world was undergoing significant transformations, from the lingering influence of Neoclassicism and Romanticism to the rise of Realism and, later, Impressionism.

His teacher, Pierre-Dominique Le Camus, was a product of the studio of Jacques-Louis David. This Neoclassical titan had a profound impact on French art, and his studio was a crucible for many talented artists. Among those who worked with or were trained by Jacques-Louis David, and thus part of the artistic lineage that indirectly touched Jules David, were figures like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who became a champion of classical line, and painters such as Antoine-Jean Gros, François Gérard, Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson, Jean-Baptiste Wicar, Jean-Germain Drouais, and François-Xavier Fabre. Female artists also found a place in this environment, including Marie-Guillemine Benoist and Constance Mayer. While Jules David's own work did not directly emulate the grand Neoclassical style, the emphasis on precise drawing and composition from this tradition would have been beneficial.

More directly relevant to Jules David's specialization were his contemporaries in the field of fashion illustration. The 19th century saw a number of talented artists dedicated to this genre. Among the most notable were the Colin sisters: Héloïse Leloir (née Colin), Anaïs Toudouze (née Colin), and Laure Noël (née Colin). They were daughters of the painter Alexandre-Marie Colin and, like Jules David, produced a vast number of exquisite fashion plates for leading journals. Their styles were often compared, and together they dominated the field for many years.

Other illustrators active during parts of Jules David's career included Paul Gavarni (Guillaume Sulpice Chevallier), known for his witty depictions of Parisian life and manners, which often included fashionable figures, and Achille Devéria, a versatile artist who produced portraits, romantic vignettes, and fashion illustrations. These artists, each with their own stylistic nuances, contributed to the rich visual tapestry of 19th-century print culture.

It is also important to distinguish Jules David from other artists with similar names or working in related fields to avoid confusion. For instance, the aforementioned Jacques-Louis David is a completely distinct historical figure. Similarly, Jules Chéret (1836-1932), a contemporary of Jules David's later career, became famous as the "father of the modern poster," known for his vibrant, dynamic color lithographs, particularly for cabarets and products. Chéret's style, with its bold lines and bright, flat color planes, was quite different from the more delicate and detailed approach of Jules David's fashion plates.

Technical Mastery: Lithography and Hand-Coloring

The dissemination of Jules David's fashion illustrations was made possible by advancements in printmaking techniques. Lithography, invented in the late 18th century by Alois Senefelder, became widely adopted in the 19th century for its ability to produce a large number of prints relatively cheaply and to capture the artist's touch more directly than earlier methods like engraving or etching. Many of David's fashion plates were lithographs. Steel engraving was also used, allowing for very fine lines and a high number of impressions before the plate wore out.

The appeal of these fashion plates was greatly enhanced by hand-coloring. While color printing technologies were developing throughout the 19th century (such as chromolithography), hand-coloring remained a prevalent method for achieving nuanced and vibrant colors in fashion illustrations for a significant portion of David's career. This was a labor-intensive process, typically carried out by skilled artisans, often women, who would apply watercolors to each print according to a master copy. The quality of the hand-coloring was crucial to the final aesthetic effect, bringing the depicted fabrics and ensembles to life. Jules David's designs provided an excellent canvas for these colorists.

International Reach and Enduring Influence

As mentioned, Jules David's work was not confined to France. The Parisian fashion industry set the tone for much of the Western world, and fashion magazines played a crucial role in transmitting these trends. David's illustrations, through their publication in French journals that circulated internationally and their reproduction in foreign magazines like The Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, reached a wide readership. This helped to solidify Paris's status as the arbiter of style and made David's depictions of French elegance influential across borders.

His illustrations served multiple purposes. For the affluent woman, they were a source of inspiration and a guide to what was considered fashionable. For dressmakers and modistes, they were practical tools, providing detailed visual information about garment construction, trimmings, and overall silhouette. For social historians and fashion scholars today, they are invaluable primary source documents, offering a detailed and extensive visual record of 19th-century clothing and, by extension, insights into the social customs, gender roles, and aesthetic preferences of the era.

The consistency and longevity of his career meant that he documented several distinct fashion periods, from the Romantic era's sloping shoulders and bell-shaped skirts, through the crinoline period's expansive silhouettes, the bustle era's dramatic back drapery, to the more tailored styles of the late 19th century. His ability to adapt his representations to these evolving forms while maintaining a signature elegance speaks to his skill and understanding of fashion's dynamic nature.

Later Career, Legacy, and Collections

Jules David remained active as an illustrator for a remarkably long period, with his work continuing to appear into the early 1890s, shortly before his death in 1892. This demonstrates his enduring relevance in a field that was itself constantly changing with new printing technologies and artistic styles.

The legacy of Jules David is primarily that of a master fashion illustrator who meticulously and artfully chronicled the sartorial landscape of his time. His work contributed significantly to the visual culture of the 19th century and played a part in the burgeoning consumer culture that placed increasing importance on fashion as an expression of identity and social standing. While he may not be as widely known to the general public as some painters of grand historical scenes or avant-garde movements, his contribution to the history of fashion and illustration is substantial.

Regarding the presence of Jules David's original drawings, prints, or paintings in public collections, the information provided in the initial context is somewhat ambiguous and appears to conflate him with other artists, particularly Jacques-Louis David, whose works are indeed housed in major museums like the Louvre, or Michelangelo's David in the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence. For Jules David (1808-1892), the fashion illustrator, his primary output – the fashion plates – exists in numerous bound volumes of the magazines he contributed to, which are held in the collections of major libraries and museums with fashion or print collections worldwide. These include institutions like the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, among others. Original drawings or preparatory sketches for his illustrations may be rarer and more dispersed. Specific auction records for Jules David the fashion illustrator are not as prominently tracked as those for painters of unique, large-scale works, but individual plates or collections of plates do appear on the art market.

The scholarly evaluation of artists like Jules David has evolved. Initially, fashion illustration might have been seen as a more commercial or ephemeral art form compared to "high art." However, contemporary art history and cultural studies increasingly recognize the importance of such visual material in understanding social history, material culture, and the construction of gender and class identities. In this context, Jules David's work is appreciated for its artistic merit, its documentary value, and its role in the cultural fabric of the 19th century.

Conclusion: A Master of Parisian Style

Jules David was more than just a draughtsman of dresses; he was an artist who captured the spirit of Parisian elegance for over half a century. Through thousands of meticulously rendered and beautifully composed illustrations, he not only documented the changing tides of fashion but also helped to shape the very ideal of the fashionable Parisian woman that captivated the imagination of the Western world. His work for prominent journals like Le Moniteur de la Mode and Journal des Demoiselles made him a household name among those who followed fashion, and his plates served as both aspirational images and practical guides.

While his artistic training connected him indirectly to the grand traditions of French painting through his teacher Le Camus, a student of Jacques-Louis David, Jules David forged his own path in the burgeoning field of popular illustration. His dedication to his craft, his keen eye for detail, and his ability to imbue his figures with grace and sophistication set him apart. He navigated the evolving tastes and technologies of the 19th century, leaving behind a rich visual archive that continues to inform and delight.

Today, the illustrations of Jules David are prized by fashion historians, collectors of antique prints, and anyone interested in the visual culture of the 19th century. They offer a captivating glimpse into a bygone era, reminding us of the artistry involved in depicting fashion before the age of photography came to dominate the field, and securing Jules David's place as a significant chronicler of Parisian style and an important figure in the history of illustration. His extensive oeuvre stands as a testament to a career dedicated to capturing and disseminating the ephemeral beauty of fashion.