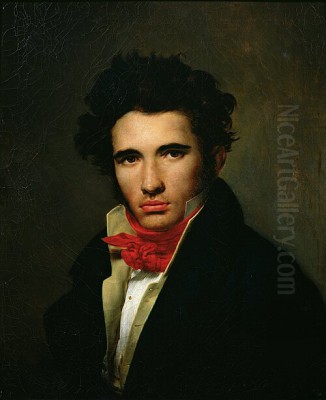

Léon Cogniet (1794-1880) stands as a significant, if sometimes underappreciated, figure in the landscape of 19th-century French art. His career spanned a period of profound artistic transformation, witnessing the zenith of Neoclassicism, the passionate rise of Romanticism, and the nascent stirrings of Realism and Impressionism. Cogniet was not merely a passive observer of these changes; he was an active participant, a respected painter of historical scenes and portraits, and, crucially, an influential educator whose teachings shaped a generation of artists. His journey from a promising student at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts to a revered master and academician offers a compelling insight into the artistic and cultural currents of his time.

Early Life and Artistic Foundations

Born in Paris in 1794, Léon Cogniet's entry into the world of art was perhaps preordained. His father was a wallpaper designer and painter, providing an early exposure to artistic creation. This familial background likely nurtured his nascent talents, leading him to formally pursue an artistic education. In 1812, at the age of eighteen, Cogniet enrolled in the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, the preeminent institution for artistic training in France. This was a critical step, placing him at the heart of the academic tradition that then dominated French art.

At the École, Cogniet had the privilege of studying under two notable masters: Pierre-Narcisse Guérin and Jean-Victor Bertin. Guérin, a student of Jean-Baptiste Regnault and a contemporary of Jacques-Louis David's pupils like Antoine-Jean Gros and François Gérard, was a prominent Neoclassical painter known for his historical and mythological subjects. His studio was a crucible for many aspiring artists, and his influence on Cogniet would have instilled a strong foundation in academic principles, including rigorous drawing, balanced composition, and the importance of historical and classical themes. Guérin himself was a bridge figure, whose later works showed some Romantic tendencies, perhaps influencing Cogniet's own stylistic evolution.

His other significant teacher, Jean-Victor Bertin, was a renowned landscape painter. Bertin was a key figure in the development of historical landscape painting, a genre that combined idealized natural settings with classical or mythological narratives. Under Bertin, Cogniet would have honed his skills in depicting nature, understanding light and atmosphere, which would prove valuable not only for pure landscapes but also as settings for his historical compositions. This dual tutelage, encompassing both figure-based historical painting and landscape, provided Cogniet with a versatile skill set.

The Pivotal Prix de Rome and Italian Sojourn

A significant milestone in any young French artist's career during this period was the Prix de Rome. This prestigious scholarship, awarded by the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture (later part of the Académie des Beaux-Arts), offered the winner a funded period of study at the French Academy in Rome. Competition was fierce, as the prize was a clear path to recognition and future commissions. In 1817, Léon Cogniet achieved this coveted honor, a testament to his talent and the quality of his training under Guérin and Bertin.

His time in Rome, from roughly 1817 to 1822, was transformative. The Eternal City offered unparalleled opportunities to study masterpieces of classical antiquity and the Renaissance firsthand. Artists like Raphael, Michelangelo, and Caravaggio provided profound lessons in composition, anatomy, and dramatic expression. During this period, Cogniet produced works such as Hermes Rescuing Hercules, demonstrating his engagement with classical mythology and the academic style favored by the Academy.

Rome was also a vibrant hub for artists from across Europe. It was here that Cogniet formed important friendships and artistic connections. He encountered fellow French artists, including the burgeoning Romantic figures Théodore Géricault, whose Raft of the Medusa would soon shock the Paris Salon, and Eugène Delacroix, who would become the leading figure of French Romantic painting. He also befriended the landscape painter Achille-Etna Michallon, another Prix de Rome winner (in historical landscape). Their shared interest in landscape painting led to productive artistic exchanges. Cogniet's painting Artist's Studio in the Villa Medici, Rome (1817) captures the atmosphere of this period, showcasing his sensitivity to light and detail in interior and landscape settings. This Italian sojourn broadened his horizons, exposing him to diverse artistic approaches and the rich tapestry of Italian art and landscape, which would continue to inform his work.

A Celebrated Career in Paris

Upon his return to Paris in the early 1820s, Léon Cogniet embarked on a successful career as a painter of historical subjects and portraits. He regularly exhibited at the Paris Salon, the official art exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which was the primary venue for artists to gain public recognition and patronage. His works from this period reflect his academic training, but also an increasing inclination towards the dramatic intensity and emotional depth characteristic of Romanticism.

Historical Masterpieces

Cogniet's historical paintings often tackled dramatic and emotionally charged subjects, distinguishing him from the more staid Neoclassicists. One of his most famous early works is The Massacre of the Innocents (1824). While the biblical subject was traditional, Cogniet's treatment was innovative. Instead of a sprawling, panoramic depiction of the slaughter, he focused intensely on the terror of a single mother desperately trying to protect her child, creating a powerful and intimate portrayal of fear and maternal love. This approach, emphasizing individual human experience within a historical or biblical narrative, became a hallmark of his style and resonated with the Romantic sensibility.

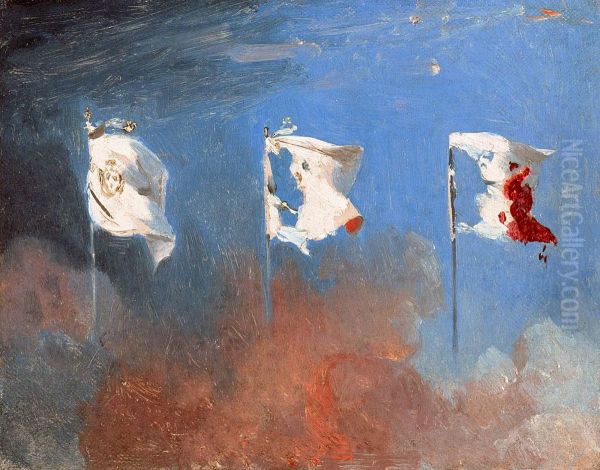

Another significant historical work is Marius on the Ruins of Carthage (circa 1830). This painting depicts the Roman general Gaius Marius in exile, a solitary and brooding figure amidst the desolate ruins of the once-great city. The work captures themes of fallen greatness, resilience, and the melancholic contemplation of history, all central to Romantic thought. The dramatic lighting and the heroic, yet tragic, posture of Marius contribute to the painting's powerful impact.

Later, in 1843 (or 1845, sources vary), Cogniet painted Tintoretto Painting His Dead Daughter (sometimes mistakenly referred to as Titian Entrusting His Daughter). This poignant work depicts the Venetian Renaissance master Jacopo Tintoretto at the easel, tenderly painting a final portrait of his deceased daughter, Maria Robusti (La Tintoretta), who was also a talented painter. The scene is imbued with profound grief and paternal love, rendered with delicate brushwork and a somber palette. It is considered one of Cogniet's most emotionally resonant and technically accomplished paintings, showcasing his ability to convey deep human feeling. He also explored exotic themes, as seen in The Italian Brigand's Wife (1825), reflecting the Romantic fascination with distant lands and unconventional characters.

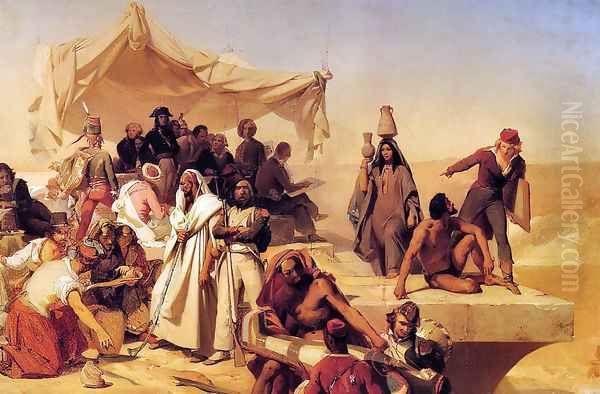

Napoleonic Grandeur and Public Commissions

Cogniet also contributed to the visual culture surrounding Napoleon Bonaparte and his legacy. Between 1833 and 1835, he worked on a series of paintings depicting The Napoleonic Expedition to Egypt. These works, often grand in scale, catered to the renewed interest in Napoleon's exploits during the July Monarchy. They combined historical accuracy with a sense of adventure and imperial ambition, characteristic of much Napoleonic art.

His reputation led to significant public commissions. He was tasked with creating ceiling paintings for the Louvre Museum. One such commission mentioned is a depiction of Saints of the Sistine Chapel (though the precise subject and location within the Louvre might require more specific art historical verification, it points to his involvement in major decorative projects). He also contributed to the decoration of important Parisian landmarks, creating murals for the Paris City Hall (Hôtel de Ville) and the Church of the Madeleine. These large-scale projects solidified his status as a leading academic painter capable of undertaking ambitious public works. Artists like Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, a staunch defender of Neoclassicism, and Delacroix, the Romantic standard-bearer, were also receiving major state commissions during this era, highlighting the competitive yet vibrant art scene.

The Evolution of an Artistic Style

Léon Cogniet's artistic style is often characterized as a bridge between Neoclassicism and Romanticism. His early training under Guérin grounded him in the formal rigor, clear linearity, and idealized forms of the Neoclassical tradition, influenced by masters like Jacques-Louis David. However, as his career progressed, Cogniet increasingly embraced the tenets of Romanticism: emotional intensity, dramatic narrative, rich color, and a focus on individual experience.

His compositions, while often carefully structured, frequently featured dynamic movement and heightened theatricality. He excelled at capturing pivotal moments of human drama, as seen in The Massacre of the Innocents and Tintoretto Painting His Dead Daughter. His figures, while anatomically correct, were imbued with expressive gestures and facial expressions that conveyed a wide range of emotions, from terror and grief to heroism and contemplation. This contrasted with the more stoic and restrained emotionality often found in stricter Neoclassical works by artists like Ingres.

Cogniet's use of color also evolved, moving towards the richer palettes and more expressive brushwork favored by Romantics like Delacroix and Géricault, though he generally maintained a greater degree of finish and polish than these more radical contemporaries. His handling of light and shadow (chiaroscuro) was often employed to create dramatic emphasis and mood, enhancing the narrative power of his scenes. In his landscape works, such as Reflections of the Moonlight on the Sea (1850-1870), he demonstrated a keen observation of atmospheric effects and the evocative qualities of nature, aligning with the Romantic appreciation for the sublime and the picturesque. His style can be seen as a more moderate form of Romanticism, one that retained respect for academic tradition while infusing it with new emotional vigor, similar in some respects to the work of artists like Paul Delaroche or Horace Vernet, who also navigated the space between these dominant artistic movements.

Cogniet the Master Educator

Beyond his own artistic production, Léon Cogniet made an indelible mark on French art as a highly respected and influential teacher. He held a professorship at the École des Beaux-Arts for many years and, in 1851, was appointed its Dean, a position of considerable authority within the French art establishment. His studio became a magnet for aspiring artists, and he is credited with teaching over one hundred students, many of whom went on to achieve significant recognition.

His teaching methods, while rooted in academic tradition, were also known for their thoroughness. He emphasized the importance of drawing from live models and plaster casts of classical sculptures, essential components of academic training designed to instill a mastery of human anatomy and form. He meticulously prepared his students for the rigorous competitions of the École and the Salon, understanding the practicalities of building an artistic career in 19th-century Paris.

Among his many notable students were:

Léon Bonnat: Who became a celebrated portrait painter, a professor at the École des Beaux-Arts himself, and a collector whose holdings formed the basis of the Musée Bonnat in Bayonne. Bonnat, in turn, taught artists like Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec and Georges Braque.

Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier: Famous for his meticulously detailed historical genre scenes and military paintings, often on a small scale but commanding high prices and immense popularity.

Viktor Madarász: A Hungarian painter who became known for his historical paintings depicting episodes from Hungarian history, imbued with a Romantic nationalist spirit.

Henri Auguste de La Rochefoucauld: A nobleman and painter.

Émile Baudouin: Another French painter.

Henri Blanc-Fontaine: Who continued his studies in Paris and became a successful painter.

Pierre-Auguste Cot: Known for his academic portraits and mythological scenes, such as the highly popular painting The Storm.

Alfred Dehodencq: A French Orientalist painter known for his vibrant depictions of life in North Africa.

Nils Blommér: A Swedish painter associated with the Düsseldorf school but who also studied in Paris.

Egron Lundgren: Another Swedish painter and writer, known for his watercolors.

It is also sometimes noted that Rosa Bonheur, one of the most famous female painters of the 19th century, known for her animal paintings, may have received some instruction or guidance from Cogniet, though her primary training was with her father and Léon Cogniet's contemporary, Raymond Bonheur.

Cogniet's dedication to teaching ensured that his influence extended far beyond his own canvases, shaping the artistic development of a diverse group of painters who would contribute to various artistic movements in the latter half of the 19th century.

Embracing Innovation: Cogniet and Photography

Interestingly, Léon Cogniet displayed a forward-thinking attitude towards new technologies, particularly the nascent art of photography. In the mid-19th century, photography was a revolutionary invention, and its relationship with painting was a subject of much discussion and debate among artists. Some saw it as a threat, others as a useful tool.

Cogniet reportedly took an active interest in the medium. It is mentioned that he explored the possibilities of photographic machines, possibly during a period of study or interaction at the École Polytechnique, a leading French institution for science and engineering. He is said to have considered how photographic techniques could be applied to painting. This might have involved using photographs as aids for composition, for capturing accurate details, or for studying light and shadow. While the extent of his direct use of photography in his painting process is not always clearly documented, his openness to this new technology at a time when many academic artists were skeptical is noteworthy. This engagement places him among artists like Delacroix, who also experimented with photography as a resource.

Navigating the Art World: Reforms and Recognition

As a prominent member of the French art establishment, Léon Cogniet was inevitably involved in the art politics of his time. The 19th century saw ongoing debates about the role of the Academy, the Salon system, and the direction of art. In 1863, a particularly contentious year that saw the establishment of the Salon des Refusés (Exhibition of Rejects) due to the large number of works rejected by the official Salon jury, significant art reforms were proposed. Cogniet, despite being open to some changes, reportedly withdrew from a special advisory committee related to these reforms, perhaps indicating a complex stance or a disagreement with the proposed direction. This adherence to certain classical or academic principles, even while embracing Romanticism, sometimes placed him in a conservative position relative to more radical artistic movements.

Despite any controversies, Cogniet's artistic achievements and his contributions as an educator were widely recognized throughout his career. He received numerous honors, including the prestigious Prix de Rome early in his career. He was made a Chevalier of the Legion of Honour, a significant French order of merit. His status was further cemented by his election as a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts (an "Academician"). His reputation extended beyond France, as evidenced by his reception of a Knight's Order from the Kingdom of Prussia. These accolades underscore his esteemed position within the European art world of the 19th century.

Later Years and Enduring Legacy

Léon Cogniet continued to paint and teach into his later years, remaining an active figure in the Parisian art scene. He passed away in Paris in 1880, at the age of 86, leaving behind a substantial body of work and a significant pedagogical legacy. While his fame may have been somewhat eclipsed in the 20th century by the rise of Impressionism and Modernism, which shifted art historical focus away from academic and Romantic painters of his generation, recent scholarship has led to a renewed appreciation for his contributions.

His importance lies not only in his individual paintings, which skillfully blended academic discipline with Romantic fervor, but also in his profound impact as a teacher. Through his students, his influence permeated various strands of late 19th-century art. He represents a crucial link in the chain of artistic tradition, a master who absorbed the lessons of Neoclassicism, embraced the passion of Romanticism, and passed on his knowledge to a new generation that would, in turn, forge new artistic paths. Artists like Gustave Courbet, who championed Realism, and later Édouard Manet, a pivotal figure in the transition to Impressionism, were challenging the very academic structures that Cogniet represented, yet the foundational skills he taught remained relevant.

Conclusion

Léon Cogniet was a multifaceted artist who navigated a dynamic and transformative period in art history with skill and dedication. As a painter, he created memorable historical and allegorical works that captured the emotional intensity and narrative drive of Romanticism, while still adhering to a high degree of technical proficiency rooted in his academic training. His portraits were also well-regarded. As an educator, he was a formative influence on a multitude of artists, shaping their skills and preparing them for careers in a competitive art world. His willingness to engage with new technologies like photography further demonstrates a mind open to innovation, even while upholding many traditional values. Léon Cogniet remains a key figure for understanding the complex interplay of tradition and change in 19th-century French art, a dedicated craftsman, a passionate storyteller, and a revered mentor.