Jan de Bray stands as a significant figure in the rich tapestry of Dutch Golden Age painting. Active primarily in the vibrant artistic center of Haarlem during the 17th century, De Bray carved a distinct niche for himself through his mastery of portraiture and history painting. Born around 1627 and living until 1697, his life spanned a period of incredible artistic flourishing but also personal turmoil. He navigated the complex artistic landscape of his time, developing a style rooted in the classical tradition while engaging with the prevailing naturalism, leaving behind a body of work that reflects both technical brilliance and deep personal resonance. As an artist deeply embedded in his community and family, his paintings often offer insights into the social fabric and aspirations of Haarlem's elite, as well as the intimate world of his own kin.

De Bray's contribution lies significantly in his adherence to and promotion of Dutch Classicism, an artistic current that sought order, clarity, and idealized beauty, often drawing inspiration from classical antiquity and the Italian Renaissance. This placed him in a fascinating dialogue with other Haarlem artists, most notably the dynamic and expressive Frans Hals. While Hals captured fleeting moments and psychological immediacy with bravura brushwork, De Bray pursued a more restrained, polished, and ennobling vision. Understanding Jan de Bray requires exploring his artistic lineage, his stylistic choices, his key works, the profound tragedies that shaped his life, and his enduring, if sometimes overlooked, place in art history.

A Family Steeped in Art

Jan de Bray was born into an environment where art was not merely a profession but a way of life. His father, Salomon de Bray (1597–1664), was a highly respected and versatile figure in Haarlem's cultural scene. Salomon was not only a painter known for his history paintings and portraits, influenced by Italianate trends and Utrecht Caravaggism, but also a published poet, an architect involved in significant local building projects like the Haarlem City Hall expansion, and a town planner. Furthermore, Salomon was a key figure in the local Guild of Saint Luke, the professional organization for painters and other craftsmen, serving as its dean and helping to draft its charter. This prominent position undoubtedly provided Jan and his siblings with invaluable connections and a deep understanding of the art world's workings.

The artistic inclinations extended throughout the family. Jan's mother, Anna Westerbaen (died 1663), came from a notable family; her brother was a painter and poet. Jan had several siblings who also pursued artistic careers. His brother Dirck de Bray (c. 1635–1694) initially worked as a painter, specializing in flower still lifes and woodcuts, before joining a monastery. Another brother, Joseph de Bray (died 1664), was also a painter, known particularly for his still lifes featuring fish. The De Bray household functioned as a busy workshop, where family members likely collaborated and learned from one another, fostering an environment of shared artistic pursuit under the guidance of the patriarch, Salomon. This familial context is crucial, as Jan would later incorporate his family members into some of his most ambitious paintings.

Artistic Formation and Influences

Jan de Bray received his primary artistic training from his father, Salomon. This foundational education instilled in him the principles of Classicism that Salomon championed – an emphasis on clear composition, idealized human forms, smooth finish, and subject matter drawn from history, mythology, and the Bible. Salomon's own style, which blended Dutch sensibilities with influences absorbed from Italian art (either directly or through intermediaries like Pieter Lastman, Rembrandt's teacher), provided a strong starting point for Jan's development. The emphasis on drawing (disegno) and compositional harmony, hallmarks of the classical tradition, became central to Jan's approach.

While his father's influence was paramount, Jan de Bray matured as an artist in Haarlem, a city dominated by the towering figure of Frans Hals (c. 1582/83–1666). Hals's lively brushwork, psychological insight, and dynamic portrayal of Haarlem's citizens represented a powerful, contrasting artistic force. While De Bray clearly respected Hals, his own path diverged towards greater formality and idealization. He absorbed the Dutch capacity for realistic likeness but filtered it through a classical lens. Comparisons are also often drawn with Amsterdam portraitists like Bartholomeus van der Helst (1613–1670), who achieved immense popularity with his smooth, detailed, and flattering portraits of the Dutch elite, suggesting a shared taste among patrons for a certain polished elegance that De Bray also provided.

The Classical Ideal in Haarlem

Jan de Bray emerged as one of the leading proponents of Dutch Classicism, particularly in Haarlem. This movement, sometimes seen as a reaction against the perceived lack of decorum in more overtly naturalistic styles, gained traction around the mid-17th century. It aligned with international trends, particularly French Classicism under Louis XIV, and appealed to patrons who desired art that conveyed dignity, order, and timeless virtue. Key characteristics included balanced compositions, often based on geometric principles; idealized figures inspired by classical sculpture; clear, even lighting; a smooth, refined finish that minimized visible brushstrokes; and subject matter that emphasized noble themes from history, mythology, or scripture.

In Haarlem, De Bray and Caesar van Everdingen (1616/17–1678) were central figures of this classical current. Their work offered a distinct alternative to the energetic realism of Hals or the intimate genre scenes of Adriaen van Ostade (1610–1685). While Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669) in Amsterdam explored profound human emotion through dramatic chiaroscuro and expressive handling, De Bray and the classicists pursued a different kind of gravitas, one based on restraint, clarity, and adherence to established aesthetic ideals. De Bray’s classicism was not rigidly academic; it retained a strong Dutch grounding in observation, but consistently elevated reality towards a more harmonious and idealized vision.

The Portrait Historié: Elevating the Subject

One of Jan de Bray's most characteristic contributions was his mastery of the "portrait historié," or historical portrait. This genre involved depicting contemporary individuals, often families or groups, in the guise of figures from history, mythology, or the Bible. It was a way to flatter the sitters by associating them with heroic or virtuous characters from the past, lending their portraits an allegorical dimension and a sense of timeless significance. This practice appealed to the self-image of the Dutch elite, who saw themselves as inheritors of classical virtues and participants in a new golden age.

De Bray excelled in this genre, often using his own family members as models. His most famous example is The Banquet of Antony and Cleopatra (1669, Royal Collection, UK), where he is believed to have depicted himself, his parents (Salomon and Anna), his siblings, and possibly one of his late wives in the roles of the famous historical figures and their attendants. This complex group portrait functions simultaneously as a family portrait, a historical scene, and perhaps an allegory on themes like luxury, love, or mortality. By casting his relatives in these roles, De Bray created a work that was both deeply personal and publicly ambitious, showcasing his skill in composition, characterization, and the seamless blending of reality and historical narrative. Other artists like Govert Flinck (1615–1660) and Ferdinand Bol (1616–1680), both pupils of Rembrandt, also worked with historical themes, but De Bray's use of the specific portrait historié format, especially involving his own family, was particularly distinctive.

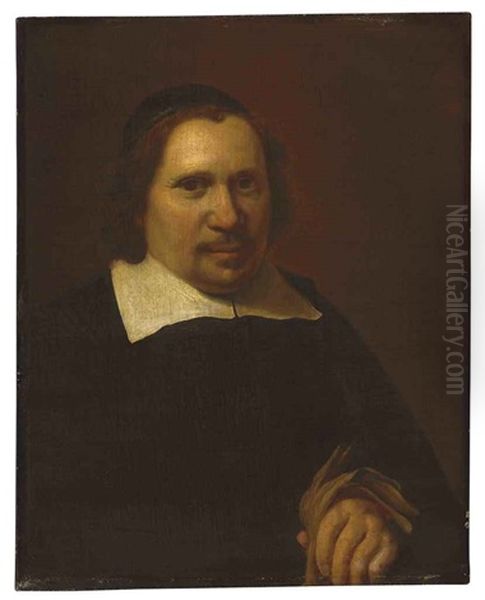

Masterpieces of Portraiture

Beyond the portrait historié, Jan de Bray was a highly accomplished portraitist in a more conventional sense, though always imbued with his classical sensibility. A standout work is the Portrait of the Artist's Parents, Salomon de Bray and Anna Westerbaen (1664, National Gallery, London). Painted shortly after their deaths during the plague epidemic, this double portrait serves as a poignant memorial. Presented in strict profile format, reminiscent of classical coins and Renaissance medals, the portraits convey immense dignity and timelessness. The format itself, possibly inspired by artists like Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) who employed similar classical devices, lends the sitters an air of historical importance.

De Bray renders his parents with meticulous detail and a smooth, enamel-like finish. Salomon appears thoughtful and distinguished, holding dividers, referencing his architectural work. Anna is depicted with quiet piety. The profile view, while limiting direct engagement with the viewer, emphasizes their noble bearing and creates a sense of enduring presence. The painting is a testament to De Bray's technical skill, his deep filial piety, and his ability to infuse portraiture with classical gravity. His individual portraits similarly combine accurate likeness with a degree of idealization, presenting sitters with clarity and composure, often against plain backgrounds that focus attention on the subject's character and status.

Grand Historical and Allegorical Scenes

Jan de Bray's ambition extended to large-scale history paintings, often commissioned for public buildings or private collectors seeking grand statements. These works allowed him to fully deploy his classical principles in complex multi-figure compositions. One significant example is David and the Return of the Ark of the Covenant (1670; location varies, possibly private collection or related works exist). This subject, drawn from the Old Testament, provided ample opportunity for depicting processions, religious fervor, and dramatic narrative within an ordered compositional framework. Such works demonstrated De Bray's ability to handle complex narratives, manage numerous figures, and create scenes that were both visually impressive and morally instructive.

His Banquet of Antony and Cleopatra (versions exist, e.g., 1652, Currier Museum of Art; 1669, Royal Collection) remains one of his most discussed works in this vein. The 1669 version, particularly, is a tour de force of group portraiture disguised as history painting. The elaborate costumes, the rich setting, and the interaction between the figures showcase De Bray's skill in rendering textures and creating a convincing, albeit idealized, scene. The identification of family members adds layers of meaning, transforming the historical anecdote into a complex statement about family, status, and perhaps the vanities of life, viewed through a classical lens. These large historical and allegorical works cemented De Bray's reputation as a painter capable of tackling the most demanding genres.

Civic Duty and Group Portraits

Like many prominent Dutch painters, Jan de Bray received commissions for group portraits, particularly of regents or governors of charitable institutions and guilds. These paintings were important civic commissions, displayed publicly to honor the sitters and commemorate their service. De Bray’s approach to group portraiture reflects his classical leanings, often resulting in more ordered and formal arrangements compared to the dynamic, snapshot-like quality found in Frans Hals’s famous militia company portraits.

His Governors of the Children's Charity House in Haarlem (1663, Frans Hals Museum) depicts the regents seated around a table, engaged in their administrative duties. While capturing individual likenesses, De Bray arranges the figures with a sense of balance and decorum. Each figure is clearly delineated, and the overall impression is one of sober responsibility and social order. Similarly, The Governors of the Guild of Saint Luke, Haarlem (1675, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam), where De Bray included a self-portrait, presents the guild leaders with dignity and professional pride. These works demonstrate his ability to meet the specific demands of Dutch group portraiture while maintaining his characteristic clarity and compositional control. They stand in contrast to the intimate, finely painted genre scenes of contemporaries like Gerard Dou (1613–1675) or Johannes Vermeer (1632–1675), highlighting the diversity of artistic production during the Golden Age.

A Life Marked by Tragedy

Despite his professional success and esteemed position in Haarlem society, Jan de Bray's personal life was fraught with profound loss and tragedy. The most devastating blow came during the plague epidemic that swept through Haarlem in 1663–1664. Within a short period, he lost both his parents, Salomon de Bray and Anna Westerbaen, and four of his siblings, including his brother Joseph, the still-life painter. This catastrophic event decimated his family, leaving Jan and his brother Dirck among the few survivors. The emotional toll must have been immense, casting a shadow over his life and work.

His marital life was also marked by repeated sorrow. Jan de Bray married three times, and each marriage ended tragically early. His first wife, Maria van Hees, whom he married in 1668, died the following year. He remarried in 1671 to Maria Magdalena de Meyer, who died in 1672, possibly in childbirth. His third marriage, to Victoria Stalpart van der Wielen in 1673, lasted slightly longer, but she too passed away in 1678. These successive bereavements, coupled with the earlier loss of his parents and siblings, paint a picture of a life punctuated by grief. While it is difficult to draw direct lines between personal tragedy and artistic output, the somber dignity and restrained emotion often present in his work may reflect these experiences. These losses also led to complex legal disputes over inheritances, adding financial strain to his emotional burdens.

Later Years, Amsterdam, and Financial Ruin

In the later part of his career, Jan de Bray faced increasing financial difficulties. Despite his artistic reputation and numerous commissions over the years, he struggled with debt. Around 1688, he moved from Haarlem to Amsterdam, perhaps seeking new opportunities or escaping creditors. In Amsterdam, he continued to work not only as a painter but also as an architect, contributing designs for the city's freshwater reservoir system in 1688, although this project was not ultimately successful.

His financial situation continued to deteriorate, culminating in his declaration of bankruptcy in 1689 (some sources say 1692). This was a significant fall from grace for a respected artist from a prominent family. His assets, including houses and remaining paintings, were likely liquidated to pay off debts. He died in Amsterdam in 1697 but, tellingly, was not buried until 1698 in his hometown of Haarlem, suggesting that funds for his funeral were initially lacking. His later years present a stark contrast to his earlier success, reflecting the precarious nature of artistic careers, even for talented individuals, in the competitive Dutch market. His move to Amsterdam placed him in the same city where artists like the landscape painter Jacob van Ruisdael (c. 1628/29–1682), also originally from Haarlem, worked, and where genre painters like Pieter de Hooch (1629–1684) captured scenes of domestic life.

Legacy and Art Historical Standing

Jan de Bray occupies an important, if sometimes underestimated, position in Dutch art history. He was a leading figure of the classical movement in Haarlem, offering a refined and idealized alternative to the dominant realism of the era. His technical skill was considerable, evident in the smooth finish, accurate drawing, and balanced compositions of his works. His mastery of the portrait historié was particularly notable, allowing him to blend portraiture, history, and allegory in innovative ways. His group portraits stand as significant examples of the genre, reflecting the civic pride and social structures of the Dutch Republic.

For a long time, De Bray's reputation was somewhat overshadowed by artists like Rembrandt, Vermeer, and Frans Hals, whose styles perhaps aligned more closely with later tastes for expressive brushwork or intimate realism. The classical tradition he represented fell out of favor for periods, leading to less critical attention. However, in recent decades, there has been a growing reassessment of Dutch Classicism and De Bray's role within it. Scholars now recognize the quality and significance of his work, appreciating its elegance, intellectual depth, and technical refinement. Exhibitions and publications have helped to bring his art to a wider audience, highlighting his contribution to the diversity of the Dutch Golden Age alongside contemporaries like the sophisticated genre and portrait painters Gerard ter Borch (1617–1681) and Gabriel Metsu (1629–1667).

Conclusion

Jan de Bray's life and art offer a compelling window into the Dutch Golden Age. Born into an artistic dynasty, he became a master craftsman and a leading exponent of Classicism in Haarlem. His paintings, whether portraits, historical scenes, or the unique portrait historié, are characterized by technical polish, compositional harmony, and an idealized yet observant approach to representation. He navigated the artistic currents of his time, creating a distinct style that emphasized dignity, order, and timeless virtue. His career, marked by both significant achievements and profound personal tragedies culminating in financial ruin, reflects the complexities and vicissitudes of life in the 17th century. While perhaps not as universally famous as some of his contemporaries, Jan de Bray remains a crucial figure for understanding the full spectrum of Dutch art, a painter whose elegant and thoughtful works continue to reward close attention.