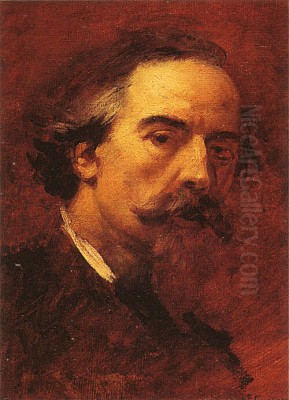

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux stands as one of the most significant and compelling figures in 19th-century French art. Born in Valenciennes on May 11, 1827, and passing away near Courbevoie on October 12, 1875, Carpeaux was primarily a sculptor, though he also practiced painting. His work pulsates with the energy, emotion, and dynamism characteristic of Romanticism, often infused with a striking realism that set him apart from the more rigid academic traditions of his time. He navigated the complex artistic and political landscape of the Second French Empire, leaving behind a legacy of powerful, expressive works that continue to captivate audiences today.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

Carpeaux hailed from a modest background in Valenciennes, a city in northern France with a rich artistic heritage. His father was a stonemason, providing an early, albeit humble, connection to the world of shaping materials. He received foundational training in drawing, sculpture, and architecture in his hometown before the family relocated to Paris. This move proved pivotal, opening doors to more advanced artistic education and exposure to the vibrant cultural scene of the capital.

In Paris, Carpeaux enrolled in the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts, the epicenter of official art training in France. There, he studied under two notable sculptors: François Rude and Francisque Duret. Rude, famous for his dynamic high-relief La Marseillaise (also known as Departure of the Volunteers of 1792) on the Arc de Triomphe, likely imparted a sense of dramatic movement and patriotic fervor. Duret, a more classically inclined sculptor, would have provided a grounding in academic principles. This dual influence shaped Carpeaux's early development, equipping him with technical skill while perhaps planting the seeds for his later departure from strict Neoclassicism.

The Prix de Rome and Italian Revelations

A crucial turning point in Carpeaux's career was winning the coveted Prix de Rome for sculpture in 1854. This prestigious prize granted him a residency at the French Academy in Rome, located in the Villa Medici. His time in Italy, extending from 1854 to 1862, was transformative. Immersed in the masterpieces of Italian art, Carpeaux absorbed the lessons of the Renaissance and Baroque periods, developing a profound admiration for masters like Michelangelo, Donatello, and Andrea del Verrocchio.

![Ugolino and his Sons [detail #4] by Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux](https://www.niceartgallery.com/imgs/140108/m/jeanbaptiste-carpeaux-ugolino-and-his-sons-detail-4-af87b5e8.jpg)

The raw power, emotional depth, and anatomical understanding of Michelangelo's work, in particular, left an indelible mark on Carpeaux. He studied Michelangelo's Pietà intensely, and this deep connection, bordering on reverence, would echo throughout his career. While some critics later accused him of merely imitating the Renaissance giant, this influence was fundamental to Carpeaux's development of a more expressive and less idealized approach to the human form.

During his Roman sojourn, Carpeaux produced several key works that signaled his burgeoning talent and evolving style. The charming Neapolitan Fisherman (also known as Fisherboy with a Shell, Pêcheur à la coquille), created around 1857-1858, captured a sense of youthful innocence and naturalism, moving away from purely classical archetypes. Another notable piece from this period is The Pouting Child (L'enfant boudeur), showcasing his ability to capture fleeting expressions and psychological states.

Ugolino and the Embrace of Drama

Perhaps the most significant work to emerge from Carpeaux's time in Rome was the harrowing group sculpture Ugolino and His Sons. Completed between 1857 and 1861 (with the bronze cast later), this piece depicts the tragic fate of Count Ugolino della Gherardesca, described in Dante Alighieri's Inferno. Ugolino, imprisoned with his sons and grandsons to starve, is shown in a moment of agonizing despair, contemplating the horrific necessity of cannibalism to survive.

Ugolino and His Sons was a bold departure from the decorum often expected by the Academy. Its raw emotional intensity, contorted figures, and exploration of extreme human suffering were deeply influenced by Michelangelo's Last Judgment and the Hellenistic sculpture Laocoön and His Sons. Carpeaux faced criticism from the academic establishment for the work's perceived lack of restraint and its focus on a gruesome subject. However, his defense of his artistic choices highlighted his commitment to emotional truth and dramatic power over neoclassical propriety. The sculpture cemented his reputation as a major talent willing to push boundaries.

Return to France and Imperial Patronage

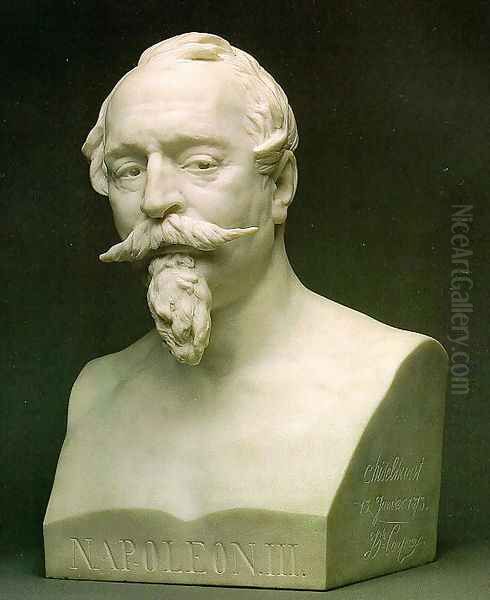

Upon his return to Paris in 1862, Carpeaux found favor within the opulent court of the Second French Empire under Napoleon III. His talent for capturing likenesses, combined with the vibrant energy of his style, appealed to the Emperor and Empress Eugénie. This imperial patronage led to numerous prestigious commissions, both for portraits and large-scale public works, making Carpeaux one of the most sought-after artists of his era.

He became the official portrait sculptor of the imperial family and court circles. His busts, such as the sensitive portrayal of Princess Mathilde Bonaparte, are renowned for their lifelike quality and psychological insight. Beyond portraiture, he was entrusted with significant decorative projects that integrated sculpture with architecture, reflecting the grandeur and ambition of the Haussmannian transformation of Paris.

Major Public Commissions: La Danse and the Fontaine de l'Observatoire

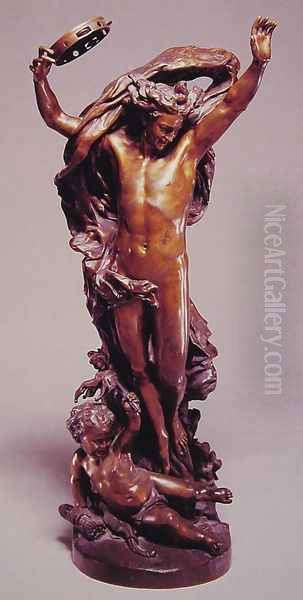

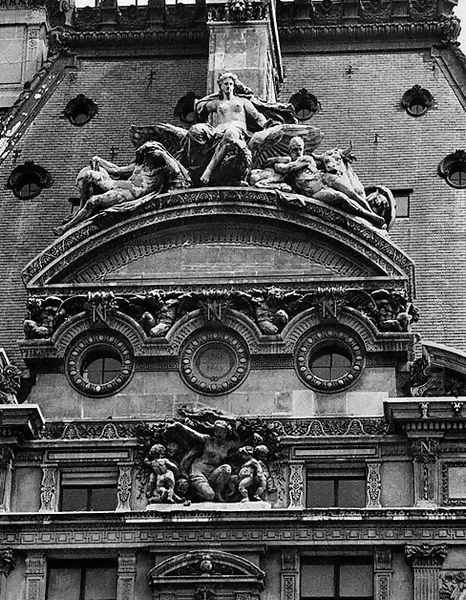

Two of Carpeaux's most famous public commissions exemplify his mature style and his ability to provoke both admiration and controversy. For the facade of the new Paris Opéra, designed by Charles Garnier, Carpeaux created the high-relief group La Danse (The Dance), unveiled in 1869. This exuberant work depicts a swirling vortex of nude figures dancing around a central, winged male figure representing the Spirit of Dance.

La Danse caused an immediate scandal. Its uninhibited energy, sensual realism, and the perceived indecency of the nude figures shocked conservative segments of the public and press. Critics decried its departure from classical grace and its perceived vulgarity. Vandals even threw ink at the sculpture shortly after its installation. Despite the controversy, or perhaps partly because of it, La Danse became iconic. Its dynamic composition and celebration of movement perfectly captured the spirit of the Opéra Garnier and solidified Carpeaux's reputation as a daring innovator. The original sculpture is now housed in the Musée d'Orsay to protect it from pollution, with a copy on the Opéra facade.

Another major public work is the Fontaine de l'Observatoire (Fountain of the Observatory), located in the Jardin du Luxembourg (though sometimes mistakenly associated with the Louvre garden or called Fontaine de l'Abondance in some sources). Commissioned in 1867 and completed after his death, the fountain's most striking element is Les Quatre Parties du Monde soutenant la sphère céleste (The Four Parts of the World Supporting the Celestial Sphere). This group features four allegorical female figures representing Europe, Asia, Africa, and America, dynamically posed as they hold aloft an armillary sphere. The figures, particularly the representation of Africa, demonstrate Carpeaux's interest in ethnographic detail and his ability to imbue allegorical figures with lifelike vitality.

Why Born Enslaved!: A Powerful Statement

Carpeaux's engagement with contemporary issues is powerfully demonstrated in his bust Pourquoi naître esclave? (Why Born Enslaved!). Created around 1868, this work depicts a bound African woman looking upward and sideways, her expression a mixture of defiance, anguish, and questioning. The sculpture emerged from studies Carpeaux made for the figure of Africa in the Fontaine de l'Observatoire.

This bust became an potent symbol within the abolitionist movement, resonating deeply in the context of the recent end of slavery in the United States and ongoing colonial exploitation. It showcases Carpeaux's ability to convey profound emotion and social commentary through the human form. The work exists in several versions and is held in major collections, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, serving as a testament to Carpeaux's humanitarian concerns and his skill in rendering expressive portraiture.

Painting and Other Works

While primarily celebrated as a sculptor, Carpeaux was also a painter. His painted works often share the same energy and focus on capturing movement and light as his sculptures. He produced portraits, genre scenes, and sketches that reveal a fluid brushwork and a keen observational eye. His Portrait de Madame Defly (1870s), housed in the Musée des Beaux-Arts in Valenciennes, demonstrates his skill in capturing personality on canvas.

His hometown museum in Valenciennes holds a significant collection of his works across different media, including sculptures like Le Printemps (Spring, 1870s) and an early Pietà (1864), showcasing the range of his production from allegorical figures to religious themes, alongside the aforementioned Fisherboy with a Shell. These works further illustrate his stylistic evolution and thematic interests.

Artistic Circle and Relationships

Carpeaux moved within the vibrant artistic circles of Paris and Rome. His relationship with his teacher, François Rude, was foundational. He also maintained connections with other artists. His friendship with the painter Jean-François Millet, known for his depictions of peasant life, was reportedly beneficial, helping Carpeaux connect with British collectors during his time in London.

During a period spent in London around 1871, fleeing the turmoil of the Franco-Prussian War and the Paris Commune, Carpeaux encountered several prominent figures. He sculpted busts of the painter Jean-Léon Gérôme, known for his Orientalist and historical scenes, and the celebrated composer Charles Gounod. He also had contact with the realist painter François Bonvin during this time.

Carpeaux's expressive style and focus on realism connected him thematically to the work of Honoré Daumier, the great caricaturist, painter, and sculptor known for his sharp social commentary, although Daumier belonged to an earlier generation. There are also stylistic affinities noted by art historians between Carpeaux's work and later painters like Eugène Carrière, known for his misty, intimate family scenes, and even Impressionists like Claude Monet in their shared interest in capturing fleeting moments, though direct interaction might be limited.

He also had a direct teaching role, influencing younger artists. The painter and printmaker Jean-Louis Forain, known for his depictions of Parisian nightlife and courtroom scenes, studied in Carpeaux's studio for a time. Carpeaux also shared a deep admiration for Michelangelo with the Swiss sculptor Adèle d'Affry, Duchess Castiglione Colonna, who worked under the pseudonym "Marcello." Sources suggest they had a friendly rapport and agreed to promote each other's work.

Personal Life: Intensity and Turmoil

Carpeaux's personal life seems to have mirrored the intensity and drama found in his art. Anecdotes paint a picture of a passionate, perhaps volatile, personality. His profound admiration for Michelangelo was a driving force, but also a point of criticism, suggesting an obsessive element to his artistic devotion.

His family life was marked by difficulty. His marriage was reportedly unhappy, and sources mention extreme behavior, including alleged violence towards his wife in his later years. This domestic turmoil might find echoes in the psychological tension of works like Ugolino. His relationship with his daughter was also complex; one anecdote mentions his refusal of a suitor for her hand, possibly due to political considerations in the turbulent post-Commune era.

Carpeaux's later years were marred by significant health problems, including what was likely cancer. Despite his physical suffering and associated mental struggles, he remained fiercely dedicated to his art, continuing to work almost until his death. This perseverance underscores his passionate commitment to his creative vision. Adding a touch of eccentricity, during his time in London, he reportedly kept pets including a bear cub, a squirrel, and a toy bear, suggesting a connection to the natural world and perhaps a whimsical side to his intense personality.

Artistic Style: From Classicism to Expressive Realism

Carpeaux's artistic journey represents a significant evolution from the Neoclassical standards prevalent in his youth towards a more dynamic and emotionally resonant Romanticism, infused with a strong dose of realism. Initially trained in the academic tradition under Rude and Duret, his early work shows a mastery of classical form and anatomy.

The Italian sojourn proved catalytic, pushing him beyond academic constraints. Exposure to Michelangelo, Donatello, and Baroque sculptors like Gian Lorenzo Bernini encouraged a greater emphasis on movement, emotional expression, and naturalism. Works like the Neapolitan Fisherman show a move towards capturing everyday life, while Ugolino fully embraces dramatic intensity.

His mature style, exemplified by La Danse and the Fontaine de l'Observatoire, is characterized by its energy, fluidity, and sensuous modeling. He broke free from the static poses and idealized forms of Neoclassicism, preferring dynamic compositions that captured figures in motion. He excelled at rendering the texture of skin, the tension of muscles, and the nuances of human expression, grounding even allegorical figures in a sense of lived reality. This blend of Romantic fervor, Baroque dynamism, and realistic observation defines his unique contribution.

Legacy and Art Historical Position

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux holds a crucial position in the history of 19th-century sculpture. He is widely regarded as the most important French sculptor of the Second Empire and a leading figure of the Romantic movement in sculpture. His work provided a vital bridge between the waning Neoclassical tradition and the emergence of modern sculpture.

His emphasis on capturing movement, emotion, and individual psychology, combined with his vigorous modeling technique, directly influenced the next generation of sculptors, most notably Auguste Rodin. Rodin admired Carpeaux's ability to imbue figures with life and energy, and echoes of Carpeaux's dynamism can be seen in Rodin's own revolutionary works.

Carpeaux challenged the conservative tastes of the French Academy and the public, expanding the boundaries of acceptable subject matter and style. While works like La Danse generated controversy, they ultimately asserted the power of a more expressive and realistic approach to the human form. His success with imperial commissions placed his innovative style at the heart of official French culture, even as it pushed against traditional norms.

Today, Carpeaux's sculptures are celebrated for their vitality, emotional depth, and technical brilliance. His major works are highlights of collections in the Musée d'Orsay, the Louvre, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C., and numerous other international institutions. He remains a pivotal figure, recognized for revitalizing the art of sculpture in France and paving the way for the modern era.

Conclusion

Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux was more than just a sculptor of the Second Empire; he was a force of nature whose work crackled with life. From his early training in Valenciennes to his formative years in Rome and his celebrated, sometimes controversial, career in Paris, he forged a unique artistic path. Deeply influenced by the masters of the past, particularly Michelangelo, he nonetheless developed a distinctly personal style characterized by dynamic movement, intense emotion, and a keen observation of reality. His masterpieces, including Ugolino and His Sons, La Danse, and Why Born Enslaved!, continue to resonate with their power and psychological depth. As a key figure of Romantic sculpture and a vital precursor to modernism, Carpeaux's legacy endures, cementing his place as one of the great sculptors in the history of art.