Pierre Puget stands as a towering, albeit sometimes controversial, figure in the landscape of 17th-century French art. A native of Marseille, born on October 16, 1620, and dying in the same vibrant port city on December 2, 1694, Puget was a polymath of the arts. He excelled as a sculptor, painter, architect, and even an engineer, leaving an indelible mark on the Baroque era. His work, characterized by its profound emotional depth, dramatic intensity, and often palpable sense of struggle, offered a powerful counterpoint to the prevailing classical restraint favored by the court of Louis XIV. Puget's art speaks of a restless, passionate spirit, one that drew deeply from Italian Baroque masters yet forged a uniquely French, and intensely personal, expression.

Early Life and Italian Immersion

Puget's artistic journey began in his native Marseille, a bustling Mediterranean hub that likely exposed him to diverse influences from a young age. His prodigious talent was evident early on. While details of his initial training in France are somewhat sparse, it is his formative years in Italy that truly shaped his artistic vision. Around the age of seventeen or eighteen, Puget traveled to Italy, the crucible of Baroque art.

In Rome, he had the invaluable opportunity to work with Pietro da Cortona, one of the leading figures of the High Baroque. This association was pivotal. Under Cortona, Puget was immersed in the dynamic world of large-scale fresco painting and architectural decoration. He is believed to have assisted Cortona in the ambitious decorative schemes for the Palazzo Barberini in Rome and later, in Florence, for the Palazzo Pitti. This experience with Cortona's exuberant, illusionistic ceilings and grand compositions undoubtedly instilled in Puget a taste for dramatic movement, rich ornamentation, and powerful emotional expression.

During his Italian sojourn, which lasted several years, Puget would have also absorbed the lessons of other giants. The overwhelming presence of Gian Lorenzo Bernini's sculptures and architectural projects in Rome, with their theatricality and technical brilliance, must have left a profound impression. Similarly, the works of sculptors like Alessandro Algardi and architects such as Francesco Borromini would have contributed to his understanding of Baroque principles. He also reportedly spent time drawing and illustrating ancient Roman monuments, possibly for Pope Urban VIII, further honing his draughtsmanship and understanding of classical forms, which he would later subvert or energize with Baroque dynamism.

Return to France: Naval Sculptor and Early Triumphs

Puget returned to France around 1643, his artistic sensibilities thoroughly imbued with the spirit of the Italian Baroque. He initially settled in Toulon, a major naval port, and Marseille. His skills were quickly put to use in a rather unconventional field for a fine artist: the decoration of warships. The great wooden galleons of the era were often elaborately adorned with monumental carvings, particularly at the prow and stern. Puget excelled in this, designing and carving colossal figures – allegories, mythological beings, and symbols of power – that were both imposing and artistically sophisticated. This work, demanding robust forms and dramatic gestures visible from afar, likely further developed his ability to handle large-scale, powerful sculpture.

Beyond ship carving, Puget also undertook commissions for paintings, including altarpieces for local churches. However, it was a sculptural commission in Toulon that truly announced his arrival as a major force. Between 1656 and 1657, he created the magnificent caryatids for the portico of the Toulon Town Hall (Hôtel de Ville). These two monumental male figures, depicted as atlantes supporting the balcony, are masterpieces of expressive power. Their strained musculature, contorted poses, and anguished expressions convey an immense sense of burden and effort. Art historians have often noted their affinity with the works of Michelangelo, particularly his "Dying Slave" and "Rebellious Slave," in their depiction of heroic suffering and intense physical tension. These caryatids were a bold statement, showcasing Puget's mastery of anatomy and his ability to imbue stone with raw emotion.

The Sculptor's Masterpieces

While Puget was versatile, sculpture became his most celebrated medium, the primary vehicle for his dramatic vision. His reputation grew, though his independent spirit and sometimes "un-French" intensity meant he wasn't always in lockstep with the official artistic doctrines emanating from Paris.

Milo of Croton: Perhaps Puget's most famous sculpture is the Milo of Croton. Commissioned by Jean-Baptiste Colbert, Louis XIV's powerful minister of finance, around 1671 and completed in 1682, it was sent to the Palace of Versailles in 1683 and is now a prized possession of the Louvre Museum. The subject is the legendary Greek athlete Milo, who, in his old age, attempted to demonstrate his enduring strength by tearing a tree trunk apart with his bare hands. The tree, however, snapped shut, trapping his hand, and he was subsequently devoured by wolves (or a lion, as Puget depicts).

Puget chose the most dramatic moment: Milo, his powerful body contorted in agony, roars in pain and terror as the lion attacks his trapped leg. The sculpture is a tour-de-force of anatomical rendering, with every muscle strained and every sinew taut. The diagonal composition, the deep undercutting creating strong chiaroscuro effects, and the raw emotionalism are pure Baroque. It was a startling work for Versailles, where sculptors like François Girardon and Antoine Coysevox were producing more classically composed and emotionally restrained pieces under the watchful eye of Charles Le Brun, the artistic director of the Royal Academies. Puget's Milo was a visceral depiction of human vulnerability and suffering, a far cry from the idealized heroism typically favored.

Perseus and Andromeda: Another significant commission for Versailles, also now in the Louvre, is Perseus and Andromeda (completed c. 1684). This group depicts the hero Perseus, fresh from slaying Medusa, swooping down to rescue Princess Andromeda, who has been chained to a rock as a sacrifice to a sea monster. Puget captures the swirling dynamism of the moment: Perseus, airborne with winged sandals, is about to strike the monster, while Andromeda looks up with a mixture of hope and terror. The composition is complex and energetic, with contrasting textures of smooth flesh, rough rock, and the monster's scales. It showcases Puget's ability to handle multi-figure compositions with dramatic flair, echoing the dynamism of Bernini's groups like Apollo and Daphne.

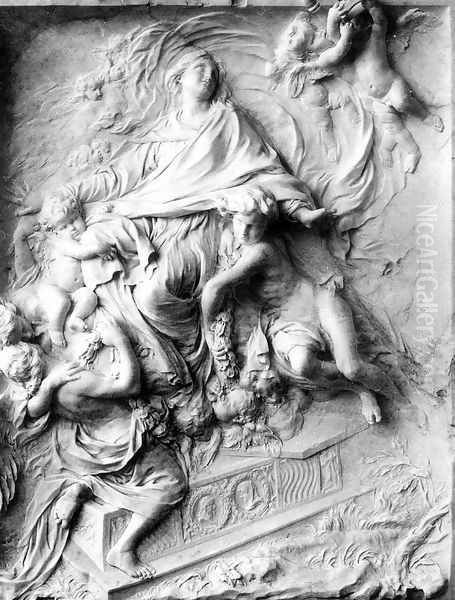

Alexander and Diogenes: Created for Versailles around 1687-1689 (though some sources suggest earlier completion and later arrival), this relief sculpture, also in the Louvre, depicts the famous encounter between Alexander the Great and the Cynic philosopher Diogenes. When Alexander, the most powerful man in the world, offered to grant Diogenes any favor, the philosopher, who lived in a barrel, famously replied, "Stand out of my light." Puget captures the contrast between imperial power and philosophical detachment. Alexander, surrounded by his retinue and magnificent steed, is depicted with regal authority, while Diogenes is a figure of rugged simplicity. The relief demonstrates Puget's skill in narrative composition and characterization.

Hercules Resting (The Gaulish Hercules): This work, often identified as Hercules Resting or the Gaulish Hercules, was originally intended for the Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte, the lavish residence of Nicolas Fouquet, before Fouquet's fall from grace. Puget later completed it (around 1661), and it eventually found its way to the Château de Sceaux. The sculpture portrays the hero Hercules, a symbol of strength and virtue, in a moment of repose, leaning on his club. Unlike the intense agony of Milo, this Hercules exudes a sense of calm power and weariness after his labors. It reflects Puget's ability to convey different emotional states, though even in repose, the figure possesses a robust physicality.

Puget the Painter and Architect

Though sculpture was his primary claim to fame, Pierre Puget was also a painter of considerable skill and an accomplished architect. His paintings, like his sculptures, often exhibit a strong sense of drama, rich color, and dynamic compositions, clearly influenced by his Italian training and masters like Pietro da Cortona. He produced numerous altarpieces for churches in Marseille, Toulon, and other parts of Provence. Works such as The Visitation, The Annunciation, and The Education of Achilles (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Marseille) showcase his painterly abilities, with fluid brushwork and a keen sense of light and shadow.

His architectural endeavors were also significant. He designed the portico of the Town Hall in Toulon, for which he famously sculpted the caryatids. In his native Marseille, he was involved in several projects. He designed the Halle de la Poissonnerie (Fish Market), a notable example of civic architecture. He also contributed designs for the Hospice de la Charité, a complex and impressive charitable institution, particularly its chapel with its elegant oval dome, which shows a sophisticated understanding of Baroque architectural principles reminiscent of Italian models. Puget also proposed a grand design for a new Place Royale and an Exchange (Bourse) in Marseille, though these ambitious plans were not fully realized due to financial or political reasons. His architectural vision extended to church design as well, with attributions including work on churches like Saint-Nicolas in Marseille and Saint-Michel in Toulouse. His architectural style, much like his sculpture, was infused with a Baroque sensibility, favoring dynamic forms, rich ornamentation, and a sense of grandeur.

A Contentious Genius: Style, Reception, and Independence

Pierre Puget's art was never entirely comfortable within the mainstream of French art during the reign of Louis XIV. The dominant aesthetic, championed by Charles Le Brun and the Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture, favored a more ordered, rational, and idealized classicism. This "Grand Style" was meant to reflect the glory and order of the French monarchy. Puget's work, with its overt emotionalism, its sometimes violent energy, and its deeply personal expressiveness, often stood in stark contrast.

His style was undeniably Baroque, characterized by:

Dynamism and Movement: Figures are rarely static, often caught in mid-action, with swirling draperies and contorted poses.

Emotional Intensity: Faces and bodies convey strong emotions – agony, terror, ecstasy, profound weariness.

Dramatic Chiaroscuro: Deep carving in sculpture and strong light/shadow contrasts in painting create theatrical effects.

Realism and Idealism: While his figures are often heroic or mythological, there's a tangible realism in their anatomy and emotional portrayal that makes them relatable.

Technical Virtuosity: Puget was a master craftsman, capable of breathtaking feats in carving marble and composing complex scenes.

This intensity, while admired by some, was viewed with suspicion by others at court, who found it perhaps too raw, too "Italianate," or lacking in the requisite decorum. Puget himself was known for his independent, even fiery, temperament. He was fiercely proud of his Provençal roots and not always willing to bend to the dictates of Parisian taste or courtly intrigue. This independence sometimes hindered his career at the highest levels. For a period, he was largely excluded from major royal commissions at Versailles.

It was through the patronage of Jean-Baptiste Colbert that Puget eventually gained significant access to Versailles. Colbert, a discerning and powerful minister, recognized Puget's exceptional talent and commissioned the Milo of Croton and Perseus and Andromeda. Even then, Puget preferred to work in his own studio in Toulon or Marseille, sending the finished works to Paris, rather than becoming a permanent fixture at the court workshops.

His relationship with other artists was complex. While he was undoubtedly aware of and responding to the work of contemporaries like Girardon and Coysevox, his path was distinctly his own. He was sometimes called the "French Michelangelo" or the "French Bernini," comparisons that highlight his ambition and power but also underscore his somewhat singular position in French art. He didn't establish a large school of followers in the same way some other court artists did, partly due to his temperament and his geographical distance from Paris for much of his career. However, he did have students, including Noël Piébourt and Gillibert Aymé, who would have absorbed his powerful style. There is also a mention of a possible, though disputed, brief tutelage under Giovanni Battista Castiglione, an Italian artist active in Genoa, a city where Puget also worked.

Later Years, Legacy, and Enduring Influence

Pierre Puget continued to work with vigor into his later years, primarily in Marseille and Toulon. He remained active in sculpture, painting, and architecture, undertaking commissions for local patrons and churches. His later works retain the power and expressiveness of his earlier periods, though some critics detect a deepening of psychological insight.

He died in Marseille in 1694, leaving behind a body of work that, while perhaps not as vast as some of his contemporaries who benefited from large royal workshops, was of consistently high quality and profound impact. For a time after his death, his reputation somewhat waned as artistic tastes shifted. However, he was never entirely forgotten, and his work experienced revivals of interest, particularly during periods that valued emotional expression and individualism.

Puget's influence, though perhaps not direct in terms of a large school, was nonetheless significant. His powerful, emotive style offered an alternative to the more rigid classicism of the Academy. Later artists who sought greater expressiveness and dynamism would find inspiration in his work. For instance, the great 19th-century sculptor Auguste Rodin, known for his own emotionally charged figures like The Thinker and The Burghers of Calais, undoubtedly shared an artistic kinship with Puget's passionate approach to the human form. Even the Post-Impressionist painter Paul Cézanne, himself a native of Provence, expressed admiration for Puget, recognizing the strength and integrity of his art and reportedly owning some of his drawings. Cézanne's own quest for structural solidity and expressive form, though manifested differently, resonates with Puget's powerful three-dimensionality.

Other artists who would have been part of Puget's broader artistic world, either as influences, contemporaries, or figures defining the contrasting artistic climate, include:

Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, whose classical landscapes and historical scenes defined an earlier phase of French classicism.

Simon Vouet, who helped introduce the Italian Baroque style to France before the rise of Le Brun.

In Italy, beyond Cortona and Bernini, Puget would have been aware of the legacy of Caravaggio and his dramatic realism, and the works of sculptors like Stefano Maderno.

In France, painters like Philippe de Champaigne represented a more austere, Jansenist-influenced classicism.

Contemporaries in Provence included painters like Jean Daret and Nicolas Mignard (though Mignard was more active in Avignon and Paris), contributing to a vibrant regional artistic scene.

Conclusion: A Singular Vision

Pierre Puget remains one of the most compelling and individualistic artists of the French Baroque. His refusal to fully conform to the prevailing artistic orthodoxies, coupled with his extraordinary talent, resulted in a body of work that is both powerful and deeply personal. Whether in the agonized form of Milo of Croton, the dynamic heroism of Perseus and Andromeda, the weighty presence of the Toulon caryatids, or the rich drama of his paintings and architectural designs, Puget's art consistently speaks with a voice of passionate conviction. He masterfully blended the lessons of Italian Baroque with his own fiery temperament and Provençal spirit, creating works that continue to captivate and move audiences with their emotional intensity and technical brilliance. He was, in essence, a force of nature in French art, a sculptor, painter, and architect whose fiery soul burned brightly against the more measured classicism of his time, leaving a legacy of unforgettable power.