François-Auguste-René Rodin, known universally as Auguste Rodin, stands as a colossus in the history of art. Born in Paris on November 12, 1840, into a modest working-class family, his life spanned a period of immense artistic upheaval and transformation. By the time of his death on November 17, 1917, he had fundamentally reshaped the landscape of sculpture, earning his place as a progenitor of modernism in the medium. His work, characterized by its raw emotional power, dynamic energy, and profound psychological insight, broke decisively with the prevailing academic traditions of his time.

Rodin's journey was not one of effortless ascent. His early artistic inclinations were met with institutional resistance. Despite demonstrating clear talent from a young age, he faced repeated rejection from the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, failing the entrance examination three times. This setback forced him onto a different path, one perhaps ultimately more formative for his unique vision. Denied formal academic training in sculpture, he honed his skills through practical application, working for nearly two decades as a craftsman and decorative sculptor for various employers, including the renowned Albert-Ernest Carrier-Belleuse.

This period, though challenging, provided Rodin with invaluable technical expertise in modeling and stone carving. It immersed him in the practicalities of the craft, far removed from the theoretical constraints of the Academy. It was during this time that he produced one of his earliest significant works, The Man with the Broken Nose (circa 1863-64). This unflinching portrait of a local handyman, with its realistic depiction of irregular features, was rejected by the Paris Salon, signaling Rodin's early departure from idealized beauty towards a more rugged, character-driven realism.

The Italian Journey and Artistic Awakening

A pivotal moment in Rodin's development came in 1875-76 with a trip to Italy. There, he encountered firsthand the masterpieces of the Renaissance, particularly the powerful works of Michelangelo. The raw energy, anatomical understanding, and profound emotional depth he witnessed in Michelangelo's sculptures left an indelible mark. He saw how form could convey intense inner struggle and spiritual aspiration, moving beyond mere representation. This experience solidified his resolve to imbue his own work with a similar vitality and psychological complexity.

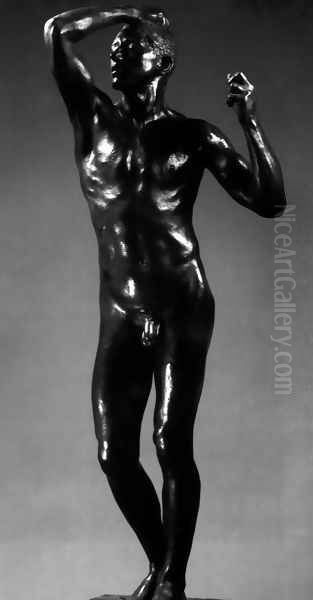

Returning to Brussels, where he was temporarily working, Rodin channeled this inspiration into his first full-scale figure, The Age of Bronze (1877). The sculpture depicted a life-sized nude male figure seemingly awakening to consciousness. Its realism was so striking, its modeling so subtle and lifelike, that it ignited a major controversy when exhibited. Critics, accustomed to the smoother, more generalized forms of academic sculpture, accused Rodin of having cast the figure directly from a live model (surmoulage), essentially cheating the artistic process.

This accusation, though unfounded, paradoxically brought Rodin significant attention. He vehemently defended his process, providing photographs of his model to demonstrate the artistic transformation involved. The scandal highlighted the gap between Rodin's intensely observed naturalism and the expectations of the art establishment. While controversial, The Age of Bronze ultimately marked Rodin's arrival as a major, albeit disruptive, force in the art world. It showcased his mastery of anatomy and his ability to convey subtle inner states through the human form.

The Gates of Hell: A Monumental Undertaking

In 1880, Rodin received a commission that would occupy him, in various forms, for the rest of his life: a set of monumental bronze doors for a planned Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. Inspired by Dante Alighieri's Inferno, the project became known as The Gates of Hell. Though the museum itself was never built and the gates were never cast in bronze during his lifetime, the project became a crucible for Rodin's creative genius. It served as a vast repository of figures and compositional ideas, many of which would later be developed into independent sculptures.

The Gates of Hell became an epic landscape of human suffering, passion, and despair. Drawing inspiration not only from Dante but also from Michelangelo's Last Judgment and the works of Charles Baudelaire, Rodin populated the doors with over 180 figures, writhing and tumbling in a turbulent composition. The overall effect is one of overwhelming, chaotic energy, a departure from the ordered narratives often found in traditional portal designs.

From this monumental matrix emerged some of Rodin's most famous works. High above the doorway sits the brooding figure originally conceived as Dante himself, surveying the infernal scene below. This figure, later enlarged and cast as an independent work, became The Thinker, an iconic image of contemplation and intellectual struggle recognized worldwide. Another celebrated group, depicting the doomed lovers Paolo Malatesta and Francesca da Rimini from Dante's poem, was extracted and developed into The Kiss, a powerful portrayal of sensual passion that contrasts sharply with the torment surrounding it on the Gates. The Three Shades, identical figures pointing down into the abyss, originally crowned the Gates, emphasizing the inescapable nature of damnation.

Masterworks of Emotion and Form

While The Gates of Hell remained a central project, Rodin simultaneously undertook other major commissions and independent works that further cemented his reputation. The Thinker, isolated from the Gates, took on a universal symbolism far beyond its original context. Its muscular form, hunched in intense concentration, speaks to the power and burden of human thought. The rough, textured surface, characteristic of Rodin's mature style, enhances the figure's raw energy and suggests the internal struggle taking place.

The Kiss, similarly, gained immense popularity as a standalone piece. Its depiction of a passionate embrace, rendered with tenderness yet undeniable physicality, became an emblem of romantic love. Unlike the idealized, often chaste lovers of academic art, Rodin's figures convey a powerful sensuality. The smooth finish of the figures contrasts with the rough-hewn rock from which they emerge, a typical Rodin device highlighting the act of creation and the figures' connection to the raw material.

Another landmark commission was The Burghers of Calais (1884-1895). Commemorating an episode during the Hundred Years' War where six prominent citizens of Calais offered their lives to save their city from the besieging English, Rodin rejected traditional heroic representations. Instead of a pyramidal composition on a high pedestal, he depicted the six men as individuals, caught in a moment of anguish, resignation, and quiet courage, walking towards their anticipated execution. He arranged them in a loose circle, emphasizing their shared fate yet individual psychological turmoil. He intended the sculpture to be placed at ground level, allowing viewers to confront the figures directly, enhancing the emotional impact. This unconventional approach initially met resistance but is now hailed as a masterpiece of psychological realism in public monuments.

Portraiture and Public Commissions

Rodin was also a sought-after portraitist, known for his ability to capture not just a physical likeness but the inner life and character of his subjects. He sculpted many prominent figures of his day, including the writer Victor Hugo. His Monument to Victor Hugo (commissioned 1889) depicts the author seated on a rocky outcrop, flanked by muses, conveying both his intellectual power and poetic inspiration.

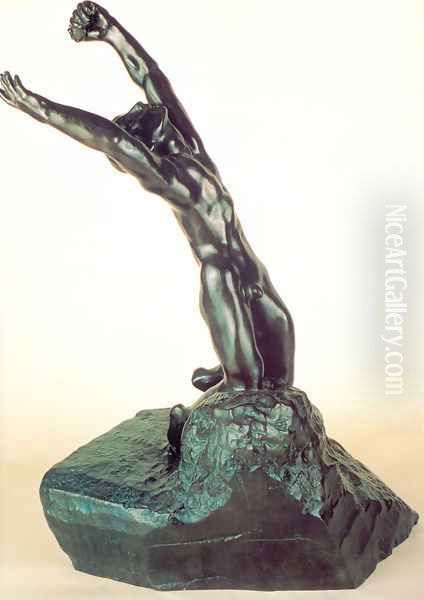

Perhaps his most controversial public work was the Monument to Balzac (commissioned 1891 by the Société des Gens de Lettres). Rodin struggled for years to capture the essence of the great novelist Honoré de Balzac. Rather than a conventional, detailed portrait, he opted for a highly abstracted, monumental figure swathed in a dressing gown (which Balzac often wore while writing), head thrown back as if in a moment of intense creative inspiration. The focus was entirely on capturing the writer's formidable creative energy.

When the plaster model was exhibited in 1898, it caused an uproar. Critics and the public derided it as grotesque, unfinished, a "sack of coal." The Société rejected the work, and the scandal was immense. Rodin, deeply wounded, withdrew the plaster to his home in Meudon. Despite the rejection, the Balzac is now considered by many art historians to be one of Rodin's greatest achievements and a foundational work of modern sculpture, prioritizing expressive force over literal representation. It demonstrated his willingness to push boundaries, even at the cost of public acceptance.

Rodin's Studio and Working Methods

Rodin's studio was a hive of activity, employing numerous assistants, modelers, and carvers. His process often began with small clay or plaster sketches, rapidly capturing poses and gestures. He relied heavily on live models, whom he encouraged to move freely around the studio, allowing him to observe the human body in natural, unposed states. He would capture fleeting moments of movement and emotion in quick sketches or small models. This contrasted sharply with the static, academic poses typically demanded of models.

His long-term partner, Rose Beuret, was an early model. Later, the talented young sculptor Camille Claudel became his student, collaborator, model, and lover. Their intense and tumultuous relationship profoundly affected both artists' work. Claudel was a gifted sculptor in her own right, and the extent of her contribution to works produced in Rodin's studio during their association remains a subject of discussion among scholars. Assistants like Antoine Bourdelle also worked under him, later becoming significant sculptors themselves.

Rodin often assembled works from existing parts – torsos, limbs, heads – created for other projects, particularly The Gates of Hell. This method of fragmentation and assemblage was radical for its time, treating the partial figure as a potentially complete work of art in itself. He embraced the "unfinished" aesthetic, often leaving parts of the sculpture rough or seemingly incomplete, contrasting finished areas with raw material. This technique, influenced perhaps by Michelangelo's non-finito, emphasized the process of creation and added expressive texture. He worked primarily by modeling in clay, with plaster casts made subsequently. These plasters could then be translated into bronze using the lost-wax method or carved into marble by skilled practitioners under his supervision.

Artistic Context: Rodin and His Time

Rodin worked during a period of extraordinary artistic ferment in Europe, particularly in Paris. The mid-to-late 19th century saw the rise of Realism, championed by painters like Gustave Courbet, who focused on depicting ordinary life and the working classes without idealization. Rodin shared this commitment to depicting reality, albeit often infused with intense emotion.

He was a contemporary of the Impressionist painters – Claude Monet, Edgar Degas, Pierre-Auguste Renoir – who revolutionized painting by capturing fleeting moments of light and atmosphere in modern life. While Rodin's medium was different, he shared with the Impressionists an interest in capturing movement and the transient effects of light on surfaces. His textured bronze surfaces often catch the light in a way that creates a sense of immediacy and vibrancy, akin to the broken brushwork of Impressionist painting.

Symbolism also flourished in the later 19th century, with artists like Gustave Moreau and Puvis de Chavannes exploring themes of myth, dream, and the inner world. Rodin's work, particularly The Gates of Hell with its exploration of damnation and intense psychological states, resonates strongly with Symbolist preoccupations. He moved beyond pure realism to explore universal human emotions and existential themes. Though primarily a sculptor, his work engaged with the major artistic currents of his era, absorbing influences while forging a unique path.

Friendships and Collaborations

Despite his often solitary dedication to his work, Rodin maintained connections within the vibrant Parisian art world. His most significant friendship was arguably with the Impressionist painter Claude Monet. They likely met in the mid-1880s through mutual acquaintances such as the critic Octave Mirbeau or the dealer Paul Durand-Ruel. Their mutual respect culminated in a major joint exhibition at the Galerie Georges Petit in 1889. This prestigious show solidified both artists' reputations as leaders of the avant-garde in their respective fields.

Their correspondence reveals a deep admiration. Rodin wrote to Monet expressing "the same fraternity of soul and love of art which makes us friends forever." Monet, in turn, appreciated Rodin's powerful forms. They shared an anti-academic stance and a profound connection to observing nature – Monet through light and color, Rodin through form and movement. They even exchanged artworks; Monet gave Rodin a painting of Belle-Île, and Rodin's personal collection included several works by Monet, as well as paintings by Vincent van Gogh and Renoir.

His relationship with Camille Claudel was far more complex. Beginning as his student and assistant in the early 1880s, she became a powerful artistic force, influencing Rodin's work even as she developed her own distinct style. Their passionate affair ended painfully in the 1890s, contributing to Claudel's later mental health struggles. The dynamic between them – collaboration, influence, passion, and eventual rupture – remains a compelling and often tragic story in art history. Rodin also interacted with other figures, including writers like Rainer Maria Rilke, who served as his secretary for a time and wrote an influential monograph on the sculptor.

Controversy and Recognition

Controversy seemed to follow Rodin throughout much of his career. From the early accusations surrounding The Age of Bronze to the firestorm ignited by the Monument to Balzac, his work consistently challenged conservative tastes and academic norms. His unidealized nudes, fragmented figures, and rough surfaces were often misunderstood or deliberately attacked by critics wedded to neoclassical smoothness and finish. His use of sensuality and overt emotion in works like The Kiss also drew criticism in some quarters.

However, alongside the criticism, recognition grew steadily, particularly from progressive critics, fellow artists, and international collectors. The 1889 exhibition with Monet was a turning point. By 1900, Rodin organized a major solo exhibition in a specially built pavilion outside the Exposition Universelle in Paris. This retrospective showcased the breadth and power of his work and significantly boosted his international fame. He received commissions from around the world and became a celebrated figure, influencing artists far beyond France.

Despite achieving widespread fame and financial success in his later years, the earlier struggles and controversies shaped his path. He remained an independent force, largely outside the official structures of the French art establishment from which he had once been rejected. His eventual renown was a testament to his perseverance and the undeniable power of his artistic vision. In 1916, shortly before his death, Rodin bequeathed his studio contents – sculptures, drawings, and his personal art collection – to the French state, leading to the creation of the Musée Rodin in Paris, housed in the Hôtel Biron where he had lived and worked.

Influence and Legacy

Auguste Rodin's impact on the course of sculpture is immeasurable. He is widely regarded as the watershed figure separating traditional sculpture from modern sculpture. He liberated the medium from the constraints of idealized forms and narrative conventions, paving the way for the radical experiments of the 20th century. His emphasis on emotional expression, the dynamism of the human body, and the expressive potential of the sculptural surface itself opened up new possibilities.

His influence can be seen directly in the work of his students and assistants, such as Antoine Bourdelle and Aristide Maillol, who, while developing their own styles, carried forward aspects of his approach to form and monumentality. More profoundly, his innovations resonated with subsequent generations. Constantin Brancusi, who briefly worked in Rodin's studio before famously declaring that "nothing grows under big trees," nonetheless absorbed lessons about simplifying form and truth to materials, even as he moved towards greater abstraction.

Sculptors like Alberto Giacometti explored themes of existential isolation and the fragmented figure, echoing Rodin's psychological depth. Henry Moore, the great British modernist, acknowledged Rodin's influence, particularly in the handling of monumental forms and the relationship between figure and landscape. Rodin's willingness to leave works "unfinished," his use of fragmentation (the partial figure as a complete statement), and his focus on the process of making all became key elements of modernist sculptural practice. His legacy endures not only in his own powerful works, housed in the Musée Rodin and collections worldwide, but also in the countless artists who followed the paths he opened.

Conclusion: Bridging Worlds

Auguste Rodin occupies a unique position in art history, acting as a bridge between the traditions of the past and the radical innovations of the future. He possessed a deep understanding and respect for the masters like Michelangelo, yet he refused to be confined by academic dogma. He infused the classical tradition of figurative sculpture with a modern sensibility, prioritizing psychological truth and emotional intensity over idealized perfection.

His sculptures capture the complexities of the human condition – love, despair, thought, struggle, ecstasy – with an unprecedented directness and physicality. Through his bold handling of form, his innovative techniques, and his willingness to court controversy, Rodin redefined what sculpture could be. He transformed it from a practice often bound by convention into a vital, expressive medium capable of conveying the turbulence and dynamism of modern life. More than a century after his death, his works continue to fascinate and move audiences, securing his legacy as a true giant of modern art.