Jean-Baptiste Debret stands as a pivotal figure in the art history of both France and Brazil. A product of the rigorous Neoclassical tradition, his journey to Brazil as part of the French Artistic Mission in the early 19th century transformed him into an invaluable chronicler of a nation in transition. His meticulous observations, rendered in paintings, watercolors, and prints, offer an unparalleled visual record of Brazilian society, from its imperial court to the daily lives of its diverse populace, including the harsh realities of slavery and the customs of its indigenous peoples. This article delves into the life, work, and enduring legacy of an artist whose European training met the vibrant, complex realities of a New World, leaving behind a rich tapestry of images that continue to inform and fascinate.

Early Life and Artistic Formation in Paris

Born in Paris on April 18, 1768, Jean-Baptiste Debret was immersed in an environment ripe with artistic and intellectual fervor. His familial connections provided a significant early advantage; he was the cousin of the preeminent Neoclassical painter Jacques-Louis David (1748-1825), who would become his mentor. Under David's tutelage, Debret absorbed the tenets of Neoclassicism, a movement that emphasized order, clarity, idealized human forms, and themes drawn from classical antiquity and historical events. David's studio was a crucible of artistic talent, producing artists like Antoine-Jean Gros (1771-1835), François Gérard (1770-1837), and the later master Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780-1867), all of whom shaped the course of French art.

Debret's early training focused on mastering draftsmanship, anatomical precision, and the grand compositions characteristic of historical painting. He proved to be a proficient student, and his talent was recognized in 1785 when he was awarded the prestigious Prix de Rome. This coveted prize enabled him to travel to Italy for further study, a customary step for aspiring history painters. In Rome, he would have been exposed to the masterpieces of classical sculpture and Renaissance art, further solidifying his Neoclassical foundations. His time in Italy, a period of intense study and artistic development, prepared him for a career that, while rooted in French academic traditions, would take an unexpected and historically significant turn.

Upon his return to France, Debret continued to work within the Neoclassical idiom, producing historical and allegorical paintings. The French Revolution and the subsequent Napoleonic era provided ample subject matter for artists, and Debret, like many of his contemporaries, contributed to the visual culture of this tumultuous period. However, his most defining artistic chapter was yet to unfold, one that would transport him far from the salons of Paris to the tropical landscapes and burgeoning society of Brazil.

The Call to Brazil: The French Artistic Mission

The year 1816 marked a significant turning point in Debret's life and career. Following the fall of Napoleon and the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in France, many artists associated with the Napoleonic regime found themselves in precarious positions. Simultaneously, the Portuguese royal court, which had relocated to Rio de Janeiro in 1808 to escape Napoleon's invasion of Portugal, sought to establish European cultural institutions in its new tropical capital. Dom João VI, then Prince Regent, envisioned transforming Rio de Janeiro into a cultural center befitting a kingdom.

This ambition led to the organization of the "Missão Artística Francesa" (French Artistic Mission), a group of French artists, architects, and artisans invited to Brazil to establish an Academy of Fine Arts and introduce European artistic practices. The mission was led by Joachim Lebreton (1760-1819), a former secretary of the Institut de France. Debret was a key member, chosen for his skills in historical painting. Other notable members included Nicolas-Antoine Taunay (1755-1830), a renowned landscape and battle painter; his brother Auguste Marie Taunay (1768-1824), a sculptor; Auguste-Henri-Victor Grandjean de Montigny (1776-1850), an architect who would design significant buildings in Rio; and Charles-Simon Pradier (1783-1847), an engraver.

Debret accepted the invitation, perhaps seeing it as an opportunity for new patronage and a chance to apply his skills in a fresh context. He arrived in Rio de Janeiro in March 1816, tasked with becoming a court painter and a professor of historical painting at the newly proposed Royal School of Sciences, Arts, and Crafts, which would later evolve into the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. This move to Brazil would immerse Debret in a society vastly different from Europe, providing him with a unique canvas for his artistic endeavors.

A New World: Debret in Rio de Janeiro

Upon his arrival in Rio de Janeiro, Debret quickly set about establishing himself. He opened a studio and began his duties as a court painter, a role that involved creating official portraits of the royal family and documenting significant state occasions. His Neoclassical training was well-suited for the grandeur and formality required of such commissions. He painted portraits of Dom João VI and later, after Brazil's independence in 1822, of Emperor Dom Pedro I and Empress Leopoldina. These works, such as the "Coronation of D. Pedro I," aimed to project an image of imperial authority and legitimacy for the newly independent nation.

Beyond his official duties, Debret was appointed professor of historical painting at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts. In this capacity, he played a crucial role in shaping the first generation of Brazilian academic painters, introducing them to European techniques and artistic theories. One of his notable students was Manuel de Araújo Porto-Alegre (1806-1879), who would later become a prominent painter, architect, writer, and director of the Academy himself. Debret's influence extended beyond mere technical instruction; he encouraged his students to observe and depict Brazilian subjects, laying a foundation for a national school of art.

However, Debret's most enduring contribution from his fifteen-year sojourn in Brazil (1816-1831) was not confined to the imperial court or the academy. He became a keen observer of the everyday life unfolding around him in Rio de Janeiro and its environs. The vibrant street scenes, the diverse population, the lush tropical landscapes, and the stark social contrasts captured his artistic imagination. He meticulously documented what he saw, moving beyond the idealized subjects of Neoclassicism to embrace a more ethnographic and documentary approach.

Documenting a Nation: Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil

The culmination of Debret's extensive observations and artistic labor in Brazil was his monumental work, Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil, ou Séjour d’un artiste français au Brésil, depuis 1816 jusqu’en 1831 inclusivement (Picturesque and Historical Voyage to Brazil, or the Sojourn of a French Artist in Brazil, from 1816 to 1831 inclusive). Published in three volumes in Paris between 1834 and 1839, after his return to France, this work is a treasure trove of lithographs based on his original watercolors and drawings, accompanied by detailed textual descriptions.

The Voyage pitoresque is encyclopedic in its scope. It covers a vast array of subjects, offering a panoramic view of early 19th-century Brazilian society. The first volume focuses on the indigenous peoples of Brazil, their customs, attire, and interactions with the colonizing society. Debret depicted various tribes, often with an ethnographic eye, though sometimes filtered through European preconceptions of the "noble savage" or the "primitive." He documented their rituals, hunting practices, and domestic life, providing valuable, if sometimes romanticized, visual records.

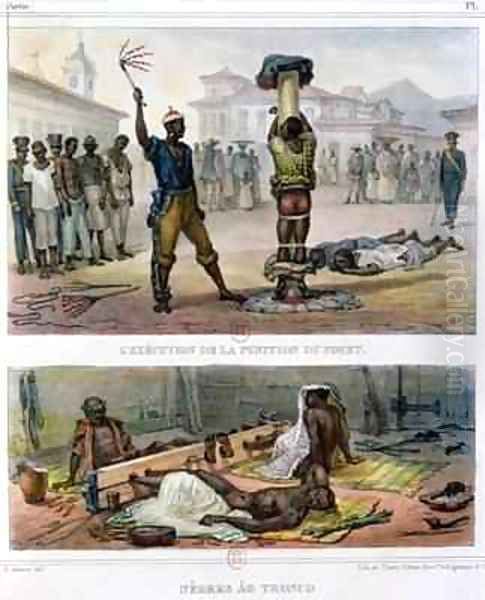

The second volume shifts to the life of the enslaved population and free people of color in urban and rural settings, particularly in Rio de Janeiro. This section is perhaps the most powerful and historically significant, as Debret did not shy away from depicting the brutal realities of slavery. His images show enslaved individuals engaged in grueling labor, being subjected to corporal punishment, and participating in the vibrant street economy as vendors, artisans, and porters. He also captured moments of their cultural expression, such as dances and religious practices.

The third volume is dedicated to the Brazilian elite, the imperial court, religious festivals, public ceremonies, and the natural landscape. It includes depictions of courtly life, military parades, popular festivals, and architectural views of Rio de Janeiro. Through these images, Debret chronicled the establishment of the Brazilian Empire and its attempts to forge a national identity. His detailed illustrations of flora and fauna, while not his primary focus, also contribute to the "picturesque" aspect of the voyage, aligning with the tradition of European scientific and artistic expeditions like those of Alexander von Humboldt (1769-1859), whose explorations inspired many artists and naturalists.

Debret's Voyage pitoresque is more than just a collection of beautiful images; it is a profound historical document. His accompanying texts provide context, personal observations, and sometimes critical commentary on the scenes he depicted. The work became an essential source for understanding Brazilian society during a formative period of its history, influencing how Brazil was perceived both domestically and internationally.

Artistic Style: Neoclassicism Meets the Tropics

Jean-Baptiste Debret's artistic style, while firmly rooted in the Neoclassicism of his master Jacques-Louis David, underwent a subtle but significant evolution during his time in Brazil. The formal compositions, clear outlines, and idealized figures characteristic of Neoclassicism remained evident, particularly in his official portraits and historical paintings for the court. Works like "The Coronation of Dom Pedro I" exhibit the grandeur, balanced composition, and attention to regal paraphernalia expected of such state commissions.

However, the unique environment and diverse human tapestry of Brazil prompted Debret to adapt his approach. When documenting everyday life, the customs of indigenous peoples, or the conditions of enslaved Africans, a greater degree of realism and ethnographic detail entered his work. His watercolors, which formed the basis for many lithographs in Voyage pitoresque, often possess a freshness and immediacy. He demonstrated a keen eye for capturing characteristic gestures, attire, and social interactions. This observational acuity, combined with a desire to record the "picturesque" and the "exotic" for a European audience, sometimes led to a style that bordered on Romanticism, with its emphasis on local color, emotion, and the particularities of different cultures.

The influence of Romantic painters like Théodore Géricault (1791-1824) and Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), who were gaining prominence in France during Debret's time in Brazil, can be subtly felt in his later Brazilian works, particularly in the empathetic portrayal of human conditions and the dramatic potential of certain scenes. While Debret never fully abandoned his Neoclassical foundations, his Brazilian oeuvre shows a flexibility and responsiveness to his subject matter that transcended strict academic formulas. He became, in essence, a visual ethnographer, using his artistic skills to document a world largely unknown to Europeans. His use of watercolor was particularly adept for capturing the vibrant light and colors of the tropics, as well as the fleeting moments of daily life.

Thematic Concerns: Society, Slavery, and the Indigenous

Debret's work in Brazil is characterized by several recurring thematic concerns, most notably his detailed exploration of Brazilian society, the institution of slavery, and the lives of indigenous peoples. His depictions of the social hierarchy are particularly insightful. He portrayed the opulent lifestyles of the white elite, the activities of merchants and artisans, and the struggles of the urban poor. His street scenes of Rio de Janeiro are bustling with activity, showcasing a diverse cast of characters – from elegantly dressed ladies and gentlemen to street vendors, porters, and beggars. These images provide a vivid sense of the social fabric of the city.

His portrayal of slavery is one of the most compelling and historically significant aspects of his work. Debret did not sanitize the institution. His images, such as "Feitors corrigindos negros" (Overseers Punishing Blacks) or scenes of slaves carrying heavy loads or being sold in markets, are unflinching in their depiction of the brutality and dehumanization inherent in the slave system. One particularly famous image shows a white family dining while, in the same room, an enslaved person is being whipped. These visual testimonies are invaluable for understanding the pervasiveness and cruelty of slavery in 19th-century Brazil. While his perspective was that of an outsider, and his work was intended for a European audience, his detailed renderings offer a powerful critique, whether explicit or implicit.

Debret also dedicated considerable attention to Brazil's indigenous populations. He depicted various groups, such as the Puri, Coroado, and Botocudo, documenting their attire, weaponry, rituals, and dwellings. While these images sometimes reflect European stereotypes of "savagery" or "primitivism," they also convey a sense of dignity and cultural distinctiveness. He was interested in their customs and their relationship with the encroaching colonial society, often portraying them in a state of transition or conflict. His work in this area can be compared to earlier European artists who documented the New World, such as the Dutch painters Frans Post (1612-1680) and Albert Eckhout (c. 1610-1665), who worked in Dutch Brazil in the 17th century, though Debret's focus was more on the human element and social customs.

Contemporaries and Collaborations

During his formative years in Paris, Debret was surrounded by the towering figures of Neoclassicism, primarily his cousin and teacher, Jacques-Louis David. David's studio was a hub of artistic activity, and Debret would have interacted with fellow students who became prominent artists, including Antoine-Jean Gros, known for his Napoleonic battle scenes, François Gérard, a celebrated portraitist, and the younger Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, who would become a pillar of French academic art. These artists, while developing their own distinct styles, shared the Neoclassical emphasis on line, form, and historical or mythological subject matter.

In Brazil, Debret was part of the French Artistic Mission, which included other significant artists. Nicolas-Antoine Taunay, a landscape painter, brought his expertise in depicting nature and historical scenes, though his stay in Brazil was shorter than Debret's. Auguste-Henri-Victor Grandjean de Montigny, the architect, left a lasting mark on Rio's urban landscape. The collective aim of the Mission was to establish European artistic standards and institutions, and Debret's role as a history painter and teacher was central to this.

Perhaps Debret's most notable contemporary working in Brazil around the same time, though not part of the official French Mission, was the German artist Johann Moritz Rugendas (1802-1858). Rugendas traveled extensively throughout Brazil between 1822 and 1825 and later published his own illustrated account, Malerische Reise in Brasilien (Picturesque Voyage in Brazil), in 1835. While both artists aimed to document Brazil for a European audience, their approaches differed. Rugendas often focused more on landscapes, panoramic views, and the dynamic portrayal of figures in action, sometimes with a more overtly Romantic sensibility. His famous work, "Capoeira or the Dance of War," captures the energy of Afro-Brazilian culture. Debret, in contrast, often provided more detailed, almost ethnographic studies of social types, customs, and the material culture of everyday life, as seen in his "Negros vendedores de Sonhos, Manuê, Aláu" (Black Vendors of Dreams, Manuê, Aláu). Their works, though distinct, are complementary and together provide an invaluable visual record of 19th-century Brazil.

Other European artists also visited or worked in Latin America during this period, contributing to a growing body of "voyage" art, such as the British artist Augustus Earle (1793-1838), who also spent time in Brazil. These artists, including Debret and Rugendas, played a crucial role in shaping European perceptions of the newly independent nations of the Americas.

Return to France and Later Years

In 1831, after fifteen years in Brazil, Jean-Baptiste Debret returned to France. The political situation in Brazil had become unstable with the abdication of Dom Pedro I, and Debret may have felt his position was less secure. Upon his return, he dedicated himself to organizing his vast collection of drawings and watercolors and preparing them for publication as Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil. This monumental task occupied him for several years, with the volumes appearing between 1834 and 1839.

The publication of his work brought him recognition in France and provided Europeans with an unprecedented visual insight into Brazilian life. He continued to paint and exhibit, and in 1839, he was elected a member of the Académie des Beaux-Arts in Paris, a testament to his standing in the French art world. His later works in France often revisited Brazilian themes or drew upon his experiences there, but the Voyage pittoresque remained his most significant achievement.

Despite the importance of his Brazilian chronicle, Debret's work, particularly his critical depictions of slavery, was not always universally acclaimed or accepted, especially within Brazil itself during certain periods. For instance, in 1840, his Voyage was reportedly rejected by the Brazilian Historical and Geographical Institute, perhaps due to its candid portrayal of sensitive social issues. However, the long-term historical and artistic value of his work would eventually transcend such contemporary reservations. Jean-Baptiste Debret passed away in Paris on June 28, 1848, leaving behind a legacy that uniquely bridges French and Brazilian art history.

Debret's Enduring Legacy

Jean-Baptiste Debret's legacy is multifaceted and profound. In France, he is remembered as a skilled Neoclassical painter, a student of David, and a member of the prestigious Académie des Beaux-Arts. However, it is his work in Brazil that has secured his most distinctive place in art history. He is considered one of the most important foreign artists to have documented Brazil, providing an invaluable visual archive of the country during a critical period of transition from colony to independent empire.

His Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil remains an essential resource for historians, anthropologists, and art historians studying 19th-century Brazil. The breadth and detail of his observations on social customs, urban life, indigenous cultures, and the institution of slavery are unparalleled. His images have been widely reproduced and continue to shape popular and scholarly understanding of Brazil's past. They offer a window into the complexities of a society grappling with independence, nation-building, and deep-seated social inequalities.

For Brazilian art, Debret's influence was foundational. As a professor at the Imperial Academy of Fine Arts, he helped train the first generation of academically-trained Brazilian artists, introducing European techniques and aesthetic principles. While the French Artistic Mission aimed to impose a European model, Debret's own extensive documentation of local subjects inadvertently encouraged a focus on Brazilian themes, contributing to the eventual development of a national artistic identity. Artists like Victor Meirelles (1832-1903) and Pedro Américo (1843-1905), though of a later generation, built upon the academic traditions established by the Mission.

In contemporary times, Debret's work is increasingly appreciated for its nuanced portrayal of Brazilian society. While subject to post-colonial critique for its European perspective, his depictions of enslaved and indigenous peoples are recognized for their ethnographic value and, often, their empathetic undertones. His visual record of the brutalities of slavery serves as a powerful historical testimony. His works are not merely picturesque; they are imbued with social commentary, making them relevant for ongoing discussions about Brazil's history, identity, and social justice.

Notable Works and Their Homes

Jean-Baptiste Debret produced a vast body of work during his lifetime, with his Brazilian period being the most prolific in terms of drawings and watercolors that would later become prints.

His magnum opus, _Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil_ (1834-1839), is not a single artwork but a collection of three volumes containing 153 lithographed plates based on his original drawings and watercolors, accompanied by extensive text. Original copies of these volumes are held in major libraries and collections worldwide, including the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.

Many of Debret's original watercolors and drawings for the Voyage are preserved in Brazilian institutions. The Castro Maya Museums in Rio de Janeiro (which include the Chácara do Céu Museum and the Açude Museum) hold a significant collection, reportedly around 490 watercolors and 61 drawings by Debret, forming the core of what is known as the "Original Album" of the Voyage pittoresque.

Specific notable paintings include:

"Coronation of Dom João VI in Rio de Janeiro" (c. 1817-1822): This historical painting, depicting the acclamation of Dom João VI as King of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil, and the Algarves, is an example of his official court art. Versions or studies may exist in various collections.

"Coronation of Dom Pedro I" (1828): This grand historical painting depicting the coronation of Brazil's first emperor is a key piece of Brazilian imperial iconography. A significant version is housed in the Itamaraty Palace in Brasília, the headquarters of Brazil's Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Another version or study is in the Museu Imperial in Petrópolis.

"Landing of the Princess Leopoldina" (c. 1817-1818): Depicting the arrival of the future Empress of Brazil in Rio de Janeiro. This work is in the collection of the Museu Histórico Nacional in Rio de Janeiro.

Individual plates from Voyage pittoresque are famous in their own right, such as:

"Um Jantar Brasileiro" (A Brazilian Dinner) – the scene depicting a family dining while a slave is whipped.

"Feitores corrigindos negros" (Overseers Punishing Blacks).

Various depictions of indigenous peoples like the "Dança dos Selvagens Puris" (Dance of the Puri Savages) or "Caboclos".

Street scenes like "Vendedores de Rua" (Street Vendors) and depictions of various trades.

Murals based on Debret's works also adorn institutions like the Museu Paulista (Ipiranga Museum) in São Paulo, further cementing his imagery in the Brazilian national consciousness. His prints can also be found in collections such as the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The widespread dissemination of his images through lithography ensured their broad impact and continued accessibility.

Conclusion

Jean-Baptiste Debret was more than just a French Neoclassical painter who ventured abroad. His fifteen years in Brazil transformed him into a meticulous chronicler, a visual ethnographer, and an unintentional social critic. Armed with the artistic tools of the European academy, he confronted the vibrant, complex, and often brutal realities of a nascent empire in the tropics. His Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil stands as a monumental achievement, offering an unparalleled window into the society, culture, and environment of early 19th-century Brazil.

While his work served the agendas of the imperial court and was intended for a European audience, its detailed and often candid depictions of everyday life, the horrors of slavery, and the customs of indigenous peoples have provided an invaluable and enduring legacy. Debret's art continues to provoke discussion, inform historical understanding, and contribute to Brazil's ongoing exploration of its own multifaceted identity. He remains a crucial figure for anyone seeking to understand the visual and social history of Brazil and the complex interplay of European art in a New World context.