Maurice Langaskens stands as a significant figure in early 20th-century Belgian art, an artist whose life and work bridged the waning influence of Symbolism and the enduring power of Realism. Born in Ghent in 1884 and passing away in Schaerbeek (Brussels) in 1946, Langaskens navigated a period of intense artistic change and profound historical upheaval. His legacy is marked by a distinctive style, a deep engagement with themes of labor, rural life, and the harrowing experiences of war, all rendered with technical skill and emotional depth. As a painter, watercolorist, and printmaker, he left behind a body of work that offers a unique window into the social and cultural landscape of his time, particularly in Belgium.

Early Life and Artistic Formation

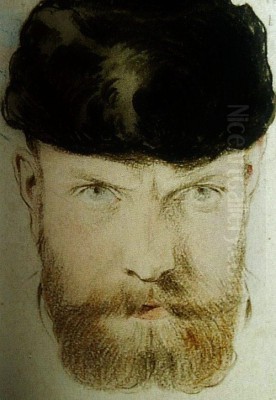

Born into an artistic family in the historic city of Ghent, Maurice Langaskens was immersed in a creative environment from a young age. This familial background likely provided early encouragement and exposure to the visual arts, setting the stage for his future path. Seeking formal training, he moved to the nation's capital and enrolled at the prestigious Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts de Bruxelles (Royal Academy of Fine Arts of Brussels) in 1901. There, he chose to specialize in decorative painting, a discipline that often emphasizes strong composition, clear lines, and harmonious color – elements that would remain visible throughout his diverse oeuvre.

His education at the Brussels Academy placed him within a crucible of artistic tradition and emerging modernism. While academic principles were still taught, the influence of newer movements was undeniable in the Belgian art scene. Following his academic training, Langaskens embarked on formative travels to France and Italy. These journeys were crucial for broadening his artistic horizons. In Italy, he dedicated time to studying the monumental frescoes of the Renaissance masters. The compositional clarity, narrative power, and enduring quality of works by artists like Giotto and Masaccio, or the serene monumentality of Piero della Francesca, likely left a lasting impression, informing his own approach to structure and form.

Furthermore, his travels exposed him to the rich legacy of Flemish art, particularly the work of the Baroque master Peter Paul Rubens. The dynamism, vibrant color palette, and sheer energy found in Rubens' paintings offered a powerful counterpoint to the more restrained qualities of Italian fresco, adding another layer of influence to Langaskens' developing artistic sensibility. These experiences abroad equipped him with a diverse visual vocabulary upon his return to Belgium.

Emergence as an Artist and Early Style

Upon returning to Belgium, Maurice Langaskens began to establish himself within the national art scene. From 1909 onwards, he became a regular exhibitor, showcasing his evolving talents to the public and critics. A significant step in his professional integration was joining the Brussels-based artistic circle "Pour l'Art" (For Art). He remained an active member of this group until 1941. "Pour l'Art" was one of several associations in Belgium at the time dedicated to promoting contemporary art, existing alongside more famous groups like "Les XX" (The Twenty) and "La Libre Esthétique," which had earlier championed artists such as James Ensor and Théo van Rysselberghe. Membership provided Langaskens with a platform for exhibition and collegial exchange.

In his early career, Langaskens' work clearly showed the influence of Symbolism and Art Nouveau, movements that had a strong presence in Belgium. Belgian Symbolism, with key figures like Fernand Khnopff, Jean Delville, and Léon Spilliaert, often explored themes of introspection, mystery, and the inner world, frequently employing evocative imagery and a refined technique. The sinuous lines, decorative patterns, and integration of art into everyday life characteristic of Art Nouveau, championed in Belgium by figures like architect Victor Horta and designer Henry van de Velde, also resonated in Langaskens' early output.

His works from this period often featured strong, clear lines, a rich and sometimes non-naturalistic use of color, and idealized depictions of rural life or symbolic themes. He explored traditional symbolic motifs, such as the figure of Saint George, embodying ideals of chivalry and struggle. A representative work like The Knight exemplifies this phase, likely displaying the decorative linearity and perhaps the medievalizing tendencies seen in some Symbolist art and influenced by movements like the Pre-Raphaelites in Britain, such as Dante Gabriel Rossetti or Edward Burne-Jones. His early paintings often presented an idyllic vision of Belgian countryside and peasant life, rendered with a distinct stylistic elegance.

The Crucible of War: Imprisonment and Artistic Response

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 dramatically interrupted Langaskens' burgeoning career and profoundly impacted his life and art. Serving in the Belgian army during the initial German invasion, he was captured and spent a significant portion of the war years, from 1914 to 1918, as a prisoner of war in Germany, primarily at the Münsterlager camp. This experience of confinement, uncertainty, and shared hardship became a central theme in his work during this period. Far from silencing his artistic voice, imprisonment spurred a remarkable period of creativity.

Langaskens produced a substantial number of drawings, watercolors, and prints documenting the daily lives, routines, and psychological states of his fellow prisoners. These works stand as a poignant testament to the realities of camp life. Titles such as Belgian Soldiers in Münsterlager Camp (1915), The Barracks (1915), The Student, and Prisoner at Work (1917) point directly to his subject matter. He depicted men reading, writing, performing manual labor, resting, or simply enduring the passage of time within the confines of the barracks and the camp grounds.

Stylistically, these wartime works often retain his characteristic strong linework and compositional sense, but the mood shifts towards a more somber and realistic portrayal. While not devoid of empathy or moments of quiet dignity, the idealism of his pre-war rural scenes gives way to a direct, observational approach focused on the human condition under duress. These works offer a powerful contrast to the often more abstract or expressionistically violent depictions of war produced by artists in other contexts, such as the German Expressionists Otto Dix or George Grosz, or the stark landscapes of British war artists like Paul Nash and C.R.W. Nevinson. Langaskens' focus remained intensely human and documentary, capturing the specific environment of the POW camp with detail and sensitivity.

Post-War Career and Evolving Themes

Following the end of the First World War and his release from captivity, Maurice Langaskens returned to Belgium and resumed his artistic career. He reintegrated into the Brussels art world, continuing his association with the "Pour l'Art" circle. The experiences of war and imprisonment left an indelible mark, yet his artistic interests remained broad, encompassing familiar themes while also reflecting his matured perspective.

His focus on the theme of labor, already present before the war, continued and perhaps deepened. Works like Workers at Work (1917, likely completed based on observations or sketches from before or during captivity), The Forge, Men Pruning Plants, and the later oil painting Retour du labeur dans un paysage enneigé (Return from Labour in a Snowy Landscape) demonstrate his sustained interest in depicting the working class and rural peasantry. These works often convey a sense of dignity and respect for physical toil, placing him in a lineage of Belgian artists concerned with social realism, most notably the sculptor and painter Constantin Meunier, known for his powerful depictions of industrial workers. Langaskens' approach, however, often retained a more painterly quality compared to Meunier's sculptural solidity, perhaps closer in spirit to the French Realist Jean-François Millet's portrayal of peasant life, albeit filtered through Langaskens' unique stylistic lens.

Alongside labor, he continued to explore landscapes, still lifes, and occasional religious or symbolic subjects. His travels and studies remained influential, but his style gradually evolved. While the strong drawing and compositional structure persisted, the overt decorative elements associated with Art Nouveau became less prominent. His work moved towards a more grounded Realism, focusing on careful observation of the everyday world, whether it be the texture of objects in a still life, the play of light on a landscape, or the posture of a worker. This shift reflected a broader trend in European art after the war, a "return to order" and a renewed interest in representational painting after the pre-war avant-garde experiments.

Artistic Style and Influences Revisited

Maurice Langaskens' artistic style is characterized by its synthesis of diverse influences and its evolution over time. A fundamental element throughout his career was his strong draftsmanship. His lines are typically clear, confident, and descriptive, defining forms with precision whether in quick sketches, detailed watercolors, or finished oil paintings. This emphasis on line likely stemmed from his training in decorative painting and was reinforced by his study of masters known for linear clarity, from Italian fresco painters to potentially the influence of printmaking traditions, perhaps even the graphic economy seen in Japanese Ukiyo-e prints by artists like Utagawa Hiroshige or Katsushika Hokusai, which had significantly impacted European art in the preceding decades.

Color was another crucial component of his art. Even when dealing with somber subjects like the POW camps, his works often exhibit a considered and sometimes surprisingly rich palette. In his pre-war and later rural scenes, color could be vibrant and expressive, contributing to the idealized or atmospheric quality of the work. His compositional skills, honed through academic training and the study of historical art, are evident in the balanced and often well-structured arrangement of his pictures. He demonstrated versatility across various media, mastering oil painting, watercolor, etching or other forms of printmaking, and mixed media techniques.

His influences were manifold. The grandeur and compositional lessons of Italian Renaissance frescoes and the dynamism of Rubens provided a historical foundation. The aesthetics of Belgian Symbolism (Khnopff, Delville) and the decorative impulses of Art Nouveau shaped his early style. The social consciousness of Realism, particularly in the Belgian tradition (Meunier) and French precedents (Millet), informed his thematic concerns with labor and everyday life. The profound personal experience of World War I acted as a catalyst, pushing his art towards a more direct, observational realism in his depictions of confinement and resilience.

Analysis of Key Works

Several works stand out as representative of Maurice Langaskens' artistic journey and thematic concerns. The Barracks at Münsterlager Camp (1915), likely executed in watercolor or ink, is a prime example of his wartime production. It probably depicts the long, communal sleeping quarters or living spaces of the prisoners. Such works typically focus on the human element within the imposed structure – figures engaged in quiet activities, the sense of waiting, the camaraderie and isolation of confinement. The style would be observational, detailed yet retaining his characteristic linear control, capturing the specific atmosphere of the camp.

The Forge or similar works depicting labor, like Workers at Work (1917), showcase his engagement with the theme of manual toil. The Forge (oil painting) likely portrays the intense heat, light, and physical exertion of blacksmiths. Compositionally, he might use strong contrasts of light and shadow to emphasize the drama of the scene and the muscular forms of the workers. These paintings celebrate the dignity and strength of the laborer, aligning with traditions of social realism but rendered with Langaskens' distinct painterly approach.

The Knight, representing his earlier phase, would embody the influence of Symbolism and Art Nouveau. The subject itself evokes medieval romance and chivalry, common themes in late 19th and early 20th-century romantic and symbolist art. Stylistically, one would expect strong outlines, possibly flattened perspectives, decorative elements in armor or background details, and perhaps a richer, more jewel-like color palette compared to his later, more realistic works. It serves as a benchmark for his stylistic evolution away from overt symbolism towards observed reality.

Retour du labeur dans un paysage enneigé (Return from Labour in a Snowy Landscape), an oil painting mentioned in auction records, likely represents his mature style. This work combines his interest in rural labor with landscape painting. The snowy setting offers opportunities for exploring specific light effects and a potentially limited but expressive color palette. The theme of returning from work suggests endurance and the rhythm of rural life, possibly depicted with a blend of realism and atmospheric sensitivity characteristic of his later period.

Langaskens and His Contemporaries

Placing Maurice Langaskens within the context of his time reveals his unique position in Belgian and European art. In Belgium, he worked alongside prominent Symbolists like Khnopff, Delville, and Spilliaert, absorbing aspects of their aesthetic in his early years. He also shared thematic ground with Realists focused on social conditions, such as Constantin Meunier. However, his path diverged from the more radical experiments emerging concurrently. While Belgian artists like Rik Wouters embraced Fauvism with its exuberant color, and others like Constant Permeke became leading figures of Flemish Expressionism with their powerful, earthy forms, Langaskens maintained a stronger connection to representational traditions, albeit infused with modern sensibilities.

Crucially, the available information and analysis of his style indicate no direct connection or significant influence from the major Parisian avant-garde movements of Fauvism or Cubism. Fauvism, spearheaded by artists like Henri Matisse and André Derain around 1905-1908, prioritized expressive, arbitrary color and bold brushwork over realistic depiction. Cubism, developed shortly after by Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, radically fragmented forms and depicted objects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously. Langaskens' consistent focus on recognizable subject matter, narrative or descriptive clarity, and a use of color tied more closely to observation or symbolic meaning, places his work distinctly apart from these revolutionary movements. His artistic concerns remained rooted in representation, human experience, and the specific cultural and social milieu of Belgium.

Furthermore, his known biography appears relatively free from major public controversies or widely circulated personal anecdotes that sometimes surround artistic figures. The narrative of his life, as presented through available sources, centers on his artistic development, his dedication to his craft, his formative travels, his membership in artistic circles like "Pour l'Art," and, most significantly, his poignant artistic response to his experiences as a prisoner of war during World War I. His story is primarily one of artistic evolution and dedicated observation.

Legacy and Collections

Maurice Langaskens' legacy lies in his contribution to Belgian art during a period of transition. He stands as a skilled and sensitive chronicler of his time, particularly notable for his extensive and moving body of work created during his WWI imprisonment. These works provide invaluable historical and human documentation of the prisoner-of-war experience. His ability to blend influences from Symbolism, Art Nouveau, and Realism into a personal style, characterized by strong drawing and expressive color, marks him as a distinctive voice. He navigated the currents of modernism while remaining committed to representational art and themes deeply connected to Belgian life and landscape.

His works are held in public collections, most notably the Flanders Fields Museum in Ypres, Belgium. This museum, dedicated to the history of World War I in the region, appropriately houses works stemming from his wartime experiences, such as portraits of fellow prisoners. It is highly probable that other major Belgian institutions, such as the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium in Brussels, also hold examples of his work, reflecting his status as a recognized national artist, although specific holdings were not detailed in the initial source material.

Langaskens' art also maintains a presence on the art market. Auction records, such as those from Arenberg Auctions, list various works appearing for sale, including watercolors like Le prisonnier (1916) and Accordéon (c. 1925), drawings like Study of a plow (c. 1910), and oil paintings like Retour du labeur dans un paysage enneigé. The estimates mentioned, ranging from modest sums for drawings to more substantial figures for significant oil paintings, indicate continued collector interest. These sales help keep his work visible and contribute to the ongoing appreciation of his artistic achievements. Maurice Langaskens remains a figure worthy of attention for his technical skill, his thematic depth, and his unique perspective on a pivotal era in Belgian and European history.